Matrix organizations

(→Fundamental overview) |

(→Fundamental overview) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

== Fundamental overview == | == Fundamental overview == | ||

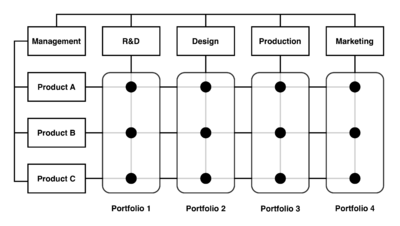

| + | [[File:Matrixorg01.png|400px|thumb|right|A typical organizational matrix structure, illustrating the functional portfolios R&D, Design, Production and Marketing of an array of products within the organization. Original illustration.]] | ||

In general, matrix organizations are implemented in order to facilitate cross-functional collaboration and improve agility within an organization. According to Jay R. Galbraith, the modern matrix management model was conceived in the 1960s, but originates from the scientific management practices and strategies developed in the early 1900s.<ref name="Galbraith"> ''Galbraith, J. R.'' (2009). ''Designing Matrix Organizations That Actually Work: How IBM, Procter & Gamble and Others Design for Success''. John Wiley & Sons.</ref> When Russia launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, the United States’ national budget priorities shifted with the initiation of the US space program. The US aerospace industry experienced rapid growth and a wide range of new projects were established within multiple organizations—most of which directly pursued John F. Kennedy’s declared goal of manned spaceflight to the moon before 1970. With three large, national programs, resources were scarce, and the United States faced a paradox of conflicting strategic priorities: the development of innovative technology as well as cost-effective and timely execution of projects. These dual strategic priorities resulted in one of the first successful matrix organizations—the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), where strong engineering functions were maintained, but with the added element of equally strong project management strategies. Project managers within NASA would henceforth report to the head of engineering as well as the organization’s general manager. | In general, matrix organizations are implemented in order to facilitate cross-functional collaboration and improve agility within an organization. According to Jay R. Galbraith, the modern matrix management model was conceived in the 1960s, but originates from the scientific management practices and strategies developed in the early 1900s.<ref name="Galbraith"> ''Galbraith, J. R.'' (2009). ''Designing Matrix Organizations That Actually Work: How IBM, Procter & Gamble and Others Design for Success''. John Wiley & Sons.</ref> When Russia launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, the United States’ national budget priorities shifted with the initiation of the US space program. The US aerospace industry experienced rapid growth and a wide range of new projects were established within multiple organizations—most of which directly pursued John F. Kennedy’s declared goal of manned spaceflight to the moon before 1970. With three large, national programs, resources were scarce, and the United States faced a paradox of conflicting strategic priorities: the development of innovative technology as well as cost-effective and timely execution of projects. These dual strategic priorities resulted in one of the first successful matrix organizations—the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), where strong engineering functions were maintained, but with the added element of equally strong project management strategies. Project managers within NASA would henceforth report to the head of engineering as well as the organization’s general manager. | ||

Revision as of 20:20, 9 May 2023

Created by Martin Sorensen

Contents |

Abstract

A matrix organization utilizes matrix management as its primary organizational structure. Within such an organization, employees have dual reporting relationships and thus report along two central chains of command. Typically, these are represented by a chain of functional value and another representing a project, product, client or market. [1] Within a matrix organization, an employee is associated with a functional manager and a project manager. While the functional manager is responsible for the expertise and technical skills of the employees, the project manager is responsible for delivering targeted project outcomes by utilization of those skills. In this manner, the titular matrix is comprised by the various intersections along the two chains of command. Matrix management differs from the similar multidimensional management style, in which many simultaneous dimensions are considered beyond the functional and e.g. client-oriented ones.

Due to the dual reporting relationship of each employee, the exact organizational form varies depending on the balance of power between the two managers. This balance is described from the perspective of the project manager, and can be either weak, balanced or strong, depending on the amount of authority they hold over the project compared to that of the functional manager.

The structure of a matrix organization is intended to address the requirements for companies that operate in dynamic and otherwise complex market environments—examples of which could be product development companies or consultancy firms. The matrix-structured approach provides an inherent flexibility by allowing internal projects to utilize the expertise of all available functional areas within the organization. This enables companies to produce rapid results without the need to realign between each project, as well as the possibility of running many different and unrelated projects in parallel.

Whilst there are many benefits to matrix organizations, their structural complexity may sometimes lead to coordination issues or internal conflict—especially in the cases where the managerial balance has not been clearly defined.

Fundamental overview

In general, matrix organizations are implemented in order to facilitate cross-functional collaboration and improve agility within an organization. According to Jay R. Galbraith, the modern matrix management model was conceived in the 1960s, but originates from the scientific management practices and strategies developed in the early 1900s.[2] When Russia launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, the United States’ national budget priorities shifted with the initiation of the US space program. The US aerospace industry experienced rapid growth and a wide range of new projects were established within multiple organizations—most of which directly pursued John F. Kennedy’s declared goal of manned spaceflight to the moon before 1970. With three large, national programs, resources were scarce, and the United States faced a paradox of conflicting strategic priorities: the development of innovative technology as well as cost-effective and timely execution of projects. These dual strategic priorities resulted in one of the first successful matrix organizations—the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), where strong engineering functions were maintained, but with the added element of equally strong project management strategies. Project managers within NASA would henceforth report to the head of engineering as well as the organization’s general manager.

It would be several years before the matrix organizational approach would be adopted in the commercial industry, but after Boeing implemented it in 1967, the organizational matrix would also bleed into the R&D community. Today, matrix management is widely regarded as the optimal way to operate R&D practices. Due to its general power balance and efficiency, the organizational matrix structure would often spread from the R&D department throughout the remainder of the organization—particularly in the case of more technological or product-oriented companies. Since then, the organizational structure of large companies has become more diffused, with many companies building their own structures slowly over time, typically aligning with the definition of multi-dimensional organizations, which focus on more elements than project and function.[2]

With two orthogonal hierarchies constituting the general structure of a matrix organization, resource allocation would in theory be improved due to the increased efficiency of collaboration and designated managerial roles. However, the intersection of these hierarchies also introduces the risk of contradicting decisions. For this reason, the matrix structure is often skewed in either of two directions, resulting in either a weak, balanced or strong matrix as described from the project manager’s perspective.

Weak matrices

In an organizational structure defined by a weak matrix, the functional manager has the highest influence on day-to-day decisions within a project. In theses cases, employees adhere to the functional chain of command, and thus primarily report to their functional manager, whilst the project manager is limited in both their authority and involvement in daily activities. In practice, this results in function-based decisions taking priority over project management-related ones.

Example: For the development of an electronic consumer Product A, a team A1 reports to both a product manager and an R&D department manager, but more often the latter. The two managers have in collaboration planned a product development schedule with Product A entering its initial testing phase within four months. However, due to the global chip shortage crisis, a component vital to the a specific product feature is in limited supply, thereby significantly delaying the project’s lead time and increasing the overall development cost of the product. The product manager suggests revising the development schedule to delay the testing phase and product launch by six months. The R&D manager disagrees, and communicates with the production manager to allocate more resources to purchasing components, thereby remaining on schedule but increasing development expenses and potential product pricing by 10%.

In the original example above, the functional manager (the R&D department manager) implemented the revised strategy and thus had higher decision power than the project manager (the manager for Product A). In these instances, it is not unusual for the project manager to work part-time and for the functional manager to be wholly responsible for the budget of the project.[3]

Balanced matrices

A balanced organizational matrix is defined by the functional manager and project manager having near equal decision power. The two parties schedule regular meetings and project-related decisions are reached unanimously. The collaborating managers are equally responsible for the project budget. Likewise, both managers are typically present and involved in daily meetings.

Example: As a response to the global chip shortage, the product manager for Product A and the R&D department manager have reached a mutual agreement to redesign the original solution, thereby relying on different components to achieve the same product feature. The result is a delay in the project’s lead time by two months and a 5% overall increase in potential product pricing. However, this decision took a significant amount of time to reach, in which the work of team A1 was largely redundant.

While the functional manager typically has a slightly higher decision power even in balanced matrix structures, they still accommodate the opinions and expertise of the project manager. This can lead to compromises such as the one shown in the example above, but also increase the risk of lengthy arbitration processes and outright conflict. Since the division of authority is not clearly defined, it may also be prone to shifting along one of the two hierarchies.[4]

Strong matrices

In a strong organizational matrix, the project manager constitutes the predominant management role. The project employees report mainly to the project manager, although the functional manager still influences the day-to-day operations in a functional or technical context. In this instance, the project manager is responsible for both scheduling and budgeting, as well as being the main authority in terms of daily executive decisions. They are typically present to every meeting and work in a full-time capacity with the team.

Example: At a weekly meeting, team A1 brings up the issue of sourcing components at the budgeted cost for the development of Product A. The global chip shortage has increased the pricing of a required component for a planned but non-vital product feature. After conversing with general management and the R&D department manager, the product manager decides to omit the discussed feature in order to remain on schedule, reduce development cost and ultimately address the introduce the feature in a future product update.

As showcased in the example above, the project manager is the general authority on both product and process-related decisions. When faced with a decision, they collaborate with actors within the organization to devise and execute a contingency plan that aligns with the original project schedule and budget.

Known use cases

Traditional functional structures run the risk of project teams becoming ‘silos’ within the company and thus hinder both dynamic management and innovation. Conversely, project-based structures can be chaotic, inflexible and often result in duplicated efforts. Matrix organizations are meant to leverage the strengths of both organizational structures in a way that allows companies to build a framework around their products and services that allows business units to collaborate directly on several projects without the need to escalate managerial decisions.[5] Today, the organizational matrix is often implemented in an international context. Unilever, Procter & Gamble and NEC are examples of companies that have adopted a matrix organizational structure in order to align goals across borders and increase overall collaboration.[6] Unilever’s various departments are strategically located based on geographic advantages. Product development activities are placed according to optimal sourcing, whilst research facilities are located in US and European population centers with high occurrences of newly educated chemists or engineers.[7]

Application

Matrix organizations are particularly useful in complex environments where multiple functions or departments need to work together to achieve a common goal. They are often used in project-based industries such as construction, software development, and aerospace, as well as in multinational corporations with diverse product lines and geographically dispersed teams. Successful implementation of a matrix structure requires clear communication channels, well-defined roles and responsibilities, and strong leadership.

Project, program and portfolio management

Multinational corporations

Innovation and agility

Implementation and maintenance

Limitations

Although matrix organizations offer a range of substantial benefits within the categories of innovation, management, and collaboration, the structure may also result in communication-related issues. These issues may encompass substantial risks, within coordination between departments and the overall power dynamics of the organization in question. Some studies suggest that a matrix organisational structure may in some cases particularly affect coordination in situations where there is a lack of clarity surrounding the division of decision-making roles within the organisational hierarchy. The specific context of the implementation, as well as the goals of the organization should therefore be considered in comparison to the general benefit that the matrix-divided decision structure can provide. A strategy to understand and mitigate risks associated with the implementation of a matrix organisational structure is to continuously monitor the effectiveness of decision-making and task management over time.

Power Struggles and Role Ambiguity

Implementing a matrix organization can be challenging, and it is important to carefully consider the specific context and goals of the organization before doing so. Some of the key challenges that can arise in matrix organizations include communication and coordination difficulties, role ambiguity, and power struggles. To address these challenges, organizations should establish clear communication channels, well-defined roles and responsibilities, and strong leadership. They should also invest in training and development to ensure that employees have the skills they need to work effectively in a matrix environment.

Communication issues

Issues with reporting

An overview of the various advantages and disadvantages can be seen in the tables below.

| Advantages[8] | Weak | Balanced | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource efficiency | High | High | High |

| Project integration | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

| Discipline retention | High | Moderate | Low |

| Flexibility | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Improved information flow | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Improved motivation and commitment | Uncertain | Uncertain | Uncertain |

| Disadvantages[8] | Weak | Balanced | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power struggles | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Heightened conflict | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Reaction time | Moderate | Slow | Fast |

| Difficulty in monitoring and controlling | Moderate | High | Low |

| Excessive overheard | Moderate | High | High |

| Experienced stress | Moderate | High | Moderate |

Annotated bibliography

References

- ↑ Stuckenbruck, L. C. (1979). The Matrix Organization. Project Management Quarterly, 10(3), 21–33

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Galbraith, J. R. (2009). Designing Matrix Organizations That Actually Work: How IBM, Procter & Gamble and Others Design for Success. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ ”Project Management Institute’' (2001). “A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK guide)”. 5th ed.

- ↑ ” Sy, T., D’Annunzio, L.S.” (2005). “Challenges and Strategies of Matrix Organizations.” Hum. Resour. Plan 28, 39.

- ↑ "Kogut, B., & Zander, U." (1996). "What firms do? Coordination, identity, and learning". Organization science, 7(5), 502-518

- ↑ "Bartlett C. A., Ghoshal S." (1998). “Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution”. (Vol. 2). Taylor & Francis, London, UK.

- ↑ "Burton, R.M., Obel, B., Håkonsson, D.D.," (2015). “How to Get the Matrix Organization to Work.”. J. Organ. Des. 4, 37. https://doi.org/10.7146/JOD.22549

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Larson, E., & Gobeli, D. (1987). Matrix Management: Contradictions and Insights. California Management Review, 29, 126-138. https://doi.org/10.2307/41162135