Project governance framework

(→Integrity Management) |

|||

| Line 256: | Line 256: | ||

[[File:project_gov_integrity.png|350px|thumb|right|Combined approach - recognizing ethics and discourse ethics <ref name="renz"/>]] | [[File:project_gov_integrity.png|350px|thumb|right|Combined approach - recognizing ethics and discourse ethics <ref name="renz"/>]] | ||

P. Renz suggests a combined approach to Integrity Management incorporating comprising the recognition of ethics and discourse of ethical guidelines. | P. Renz suggests a combined approach to Integrity Management incorporating comprising the recognition of ethics and discourse of ethical guidelines. | ||

| + | #Recognizing ethics | ||

| + | ##Emotional recognition | ||

| + | ##Legal and political recognition | ||

| + | ##Solidarity | ||

| + | #Discourse ethics | ||

| + | ##Communicative attitude | ||

| + | ##Interest for legitimate action | ||

| + | ##Differentiated responsibility | ||

| + | ##Public binding | ||

| + | |||

====Extended Stakeholder Management==== | ====Extended Stakeholder Management==== | ||

====Risk Management==== | ====Risk Management==== | ||

Revision as of 14:36, 21 February 2018

The PMI Guide on Project Management defines Project Governance as “the alignment of the project with stakeholders’ needs or objectives”. It is a critical function for the management of stakeholders and furthermore for the achievement of organizational objectives. Project governance provides the project managers and sponsors with a framework on how to make decisions to satisfy both stakeholder needs as well as organizational strategic objectives. [1] A guide by the Association of Project Management (APM) does not only consider single projects but aims to align the organization’s project portfolio to its goals. [2] A paper on a conceptual framework for project governance and the management of project management suggests that it has two key function. The first is to make decisions about which projects an organization should do and by this specify rights and responsibilities of project participants and define rules and procedures for making decisions in the projects. Secondly, project governance has an oversight and assurance function in order to support the organization’s strategy. [3] According to P. Renz, project governance closes the gap between corporate governance and the actual management of projects. It provides the project managers with more strategic and integrative solutions beyond standard project management methodologies and operationalizes the corporate governance strategy. There is not one single definition and approach for a framework that can be taken for each and every specific case. This article will define aspects of a framework, which are presented in the literature on project governance. While the APM bases its framework on adhering to different principles, P. Rentz defines a Project Governance Model based on general governance theories and resulting key responsibilities. This article will define elements of a framework for project governance from different perspectives. [4]

Contents |

Definition and Background

What is project governance?

"Project governance is a process-oriented system by which projects are strategically directed, integratively managed, and holistically controlled, in an entrepreneurial and ethically reflected way, appropriate to the singular, time-wise limited, interdisciplinary, and complex context of projects." [4] It has an oversight function which is aligned with the organization's governance model. A project governance framework provides the project manager and team with structure, processes, decision-making models and tools for managing the project, while supporting and controlling the project for successful delivery. [1] This high-level structure helps an organization to align it projects and their objectives with the organizational strategy as well as monitoring their performance. [5] Different actors and activities contribute to project governance and when effectively executed, project governance ensures that projects are delivered efficiently and sustainable while being in line with with the organisation's objectives. It also includes instructions for the board and other major stakeholders on how relevant and reliable information are exchanged between them. Summarizing, project governance helps to:

- assure boards and executives that solid governance requirements are in place across all the past and ongoing projects in an organization

- optimize the project portfolio according to strategy

- avoid common mistakes and failures in project management resulting in insufficient performance

- improve the relationships with staff, customers and suppliers

- minimize risk originating from new projects

- while maximizing the benefits realized through projects

- assure a continuing development of the organization

Why is project governance needed?

Project governance can support the successful outcome of a project in many ways. How to do project management is usually well defined within an organization and there are lots of information in- and externally on it. When it comes to more strategically problems, which are not covered within a project management framework, project managers are left without advice. The strategic and integrative nature of project governance bridges this so called "governance gap" and is going beyond standard project management methodologies. From a corporate level perspective, project governance helps to operationalize the strategy of an organization. It is linking corporate governance and strategy with the operational level, which is responsible for carrying out the projects. Through this, concerns on both levels are carried to the respective counterpart which brings them closer together. In a project oriented company, there is usually a asymmetry of information and knowledge between the project managers on the lower levels and governance boards on the upper level. Project governance overcomes this issue by being meaningful, value-adding link between project management and (corporate) governance. It institutionalizes a targeted information flow that enables the building of necessary knowledge. With this strategic orientation and a clear governance structure, it also handles multi-ownership of projects. [4]

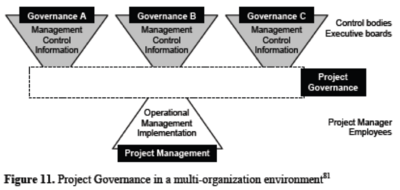

Relation to Program, Portfolio and Corporate Governance

Project governance is not one single function as e.g. a project management office. It is rather an integrative and integrating element, which is related to various program, portfolio and corporate governance as well as management. It is a linking element between all of the above, aiming to resolve the governance gap between project governance at the operational level and corporate governance at the executive level (see picture). [5] According to the PMI standards on program and portfolio management, the governance functions on those levels have relatively similar goals for the respective levels. Common objectives shared by all of the above are e.g.:

- Monitoring and controlling activities

- Aligning projects, programs, portfolios with corporate strategy

- Standard communication procedures between different levels and components

- Approaches to decision-making

As each of the governance levels has relatively similar objectives, it can be considered as a top down structure, which has to be aligned starting from the big picture considered in corporate governance and going all the way down to the specific requirements for single projects. [1] [6] [7]

Theoretical Background: Governance Theories

As project governance originates from corporate governance, different organizational theories are considered to explain the theoretical background for the necessity of different elements and key responsibilities in project governance. Based on these theories critical elements for project governance are identified and will be further explained in the following chapters.

Agency Theory

The agency theory analyses the relationship between two parties in an organization (a principal and an agent) and in general it implies that the principal faces difficulties in motivating the agent to work in a way the principal wants him to do. Because the agents need to be provided with a necessary level of decision-making authority by the principal, issues related to conflict of interest and moral hazard can arise due to asymmetric information. The fundamental assumption, this theory is based on, is that the agent is self-interested and will act opportunistically instead of just in the interest of the principal and that agents and principals may differ in their risk attitudes. The bottom line is, that agents need to get incentives, be monitored and controlled in some way.

In the context of project management and project governance, this theory is particularly used to identify a need for control between the owner and manager of a project.

Transaction cost economics

The theory of transaction cost economics is about opportunistic behavior, which may be cause by organizational actions driven by self-interest and an ambition to minimize costs. It implies that companies adapt their governance structures in order to pay the lowest possible transaction costs. Between the buyer and seller of a good is a complex relationship and behavioral factors are also considered when choosing a transaction. In general it helps to understand governance in relation to procurement and organizational decision making.

In the context of this article, the theory can e.g. explain and describe the process of assessing and selecting contractors or suppliers within a project. This implies, that there is a need in project governance for some kind of role which makes assessments and evaluations of actions within a project.

Stakeholder theory

The stakeholder theory, being based on a socially oriented perspective, focuses on a larger group than just the shareholders and it challenges assumptions of the agency theory, that the shareholder interests are primal. It implies that the management of a company should take the interests of all stakeholders (e.g. employees, suppliers, customers, environment) into account and suggests that conflicts and different interests need to be balanced between organizational shareholders

According to this theory, project governance is necessary as a strategy for project teams to understand and respond to different stakeholder groups and to coordinate with them.

Stewardship theory

In comparison to the agency theory, this theory describes human behavior in a alternative way and originates from psychology and sociology. Based on the assumption that not all organizational members (stewards) are dictated by self-interest but rather act in a collectivist way, it suggests that the stewards believe their value in the firm is increased and secured when the organization is performing good, thus try to improve organizational performance.

For the context of project governance, it can be assumed, that shareholders can be best served with empowering project managers and in the framework a role, which gives a strategic direction is necessary.

Resource dependency theory

This theory is about the allocation, prioritization and facilitation of organizational resources and implies, that success is linked to the ability of controlling interdependent external and internal resources. Resources dependency theory considers resources as they key driver in the governance structure of an organization.

It identifies the need for a linking role within project governance in order to account for the importance of allocating and prioritizing different resources, shared across projects, programs and portfolios.

Institutional theory

The institutional theory can help to understand governance in the context of social and cultural constraints, which are imposed on especially large organizations.

For project governance, it defines a "maintenance" or social role which has to handle the project in terms of societal and cultural expectations of an organization.

Framework

Since there is not one single framework, which can be taken for each specific organization and each project, the Association for Project Management (APM) defines thirteen principles instead, that should be fulfilled in order to attain successful governance for project management. Based on these, four core components of project governance are created. The APM looks at project governance from a little broader perspective and takes aspects of corporate, portfolio and program governance into account.

In the second part of this chapter, some specific modules, which are corresponding to the governance theories and the identified roles, will be explained.

Principles

These thirteen principles are based on the general requirements of governance and project management and should be followed according to the APM guide to governance of project management.

- The board has overall responsibility for the governance of project management.

- The organisation differentiates between projects and non project-based activities.

- Roles and responsibilities for the governance of project management are defined clearly.

- Disciplined governance arrangements, supported by appropriate methods, resources and controls are applied throughout the project life cycle. Every project has a sponsor.

- There is a demonstrably coherent and supporting relationship between the overall business strategy and the project portfolio.

- All projects have an approved plan containing authorisation points at which the business case, inclusive of cost, benefits and risk is reviewed. Decisions made at authorisation points are recorded and communicated.

- Members of delegated authorisation bodies have sufficient representation, competence, authority and resources to enable them to make appropriate decisions.

- Project business cases are supported by relevant and realistic information that provides a reliable basis for making authorisation decisions.

- The board or its delegated agents decide when independent scrutiny of projects or project management systems is required and implement such assurance accordingly.

- There are clearly defined criteria for reporting project status and for the escalation of risks and issues to the levels required by the organisation.

- The organisation fosters a culture of improvement and of frank internal disclosure of project management information.

- Project stakeholders are engaged at a level that is commensurate with their importance to the organisation and in a manner that fosters trust.

- Projects are closed when they are no longer justified as part of the organisation’s portfolio.

When applied, these principles avoid some common causes for project failure like:

- lack of clear link with key strategic objectives

- lack of clear senior management, ownership and leadership

- lack of effective engagement with stakeholders

- lack of skills and proven approaches to project and risk management

- lack of understanding of or contact with supply industry at senior level

- evaluation of projects is driven by initial price instead of long term value for money

- little attention to breaking down development and implementation into small and manageable steps

Core Components

Based on the thirteen principles, these four core components are key for ensuring proper governance of project management.

| Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Portfolio direction | To ensure all projects are identified within one overall portfolio, which is evaluated and directed with regard to the organization's aims, constraints, resources, capacity for change. |

| Project sponsorship | Seeks to ensure an effective link between organizations executive level and the management of each project through a project sponsorship role, which is responsible for decision making, directing and representation. |

| Project management capability | The project teams are capable of achieving goals that are defined within the project approval points and use this capability to improve governance and outcomes. |

| Disclosure and reporting | Provide timely, relevant and reliable information within the project reports, which support the organization's decision making processes. Open and honest disclosure is a key requirement for effective reporting. |

Modules

P. Renz identifies the following six modules to address the principles and required roles in project governance. The following table gives an overview of the modules, which roles they fulfill and their main objectives. Additional information on each module will be discussed in the subsections.

| Module | Role(s) | Main objectives |

|---|---|---|

| System Management | Societal role |

|

| Mission Management | Strategic, Support, Control |

|

| Integrity Management | Support |

|

| Extended Stakeholder Management | Linking, Coordinating, Control |

|

| Risk Management | Control |

|

| Audit Management | Control |

|

System Management

This module is mainly relying on two elements:

- Systemic thinking: As an integral part of the company culture, system-oriented thinking is broadly recognized. Five key characteristics are identified:

- Holistic thinking in open systems

- Analytical and synthetical thinking

- Dynamic thinking in circled processes

- Thinking in structures and information processes

- Interdisciplinary thinking

- System model: In combination with systemic thinking, a system model allows a project to be configured and managed in best possible way according to system specific circumstances. The St. Gallen Management Model could e.g. be used as such a system. It comprises six key areas:

- Environmental spheres

- Stakeholders

- Issues of interaction

- Structuring forces

- Processes

- Modes of development

Mission Management

The governance tasks corresponding to this module can be separated by the structuring force and project governance roles:

| Strategic direction and support | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy |

|

|

| Structure |

|

|

| Culture |

|

|

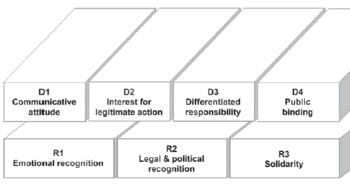

Integrity Management

P. Renz suggests a combined approach to Integrity Management incorporating comprising the recognition of ethics and discourse of ethical guidelines.

- Recognizing ethics

- Emotional recognition

- Legal and political recognition

- Solidarity

- Discourse ethics

- Communicative attitude

- Interest for legitimate action

- Differentiated responsibility

- Public binding

Extended Stakeholder Management

Risk Management

Audit Management

Limitations

...tbw

Key References

- Directing Change: APM Guide on Project governance

- Project Governance - Implementing Corporate Governance

- The management of project management: A conceptual framework for project governance

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Project Management Institute. (2004). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK guide). Newtown Square, Pa: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 PM Governance Specific Interest Group. (2011) Directing Change: A Guide to Governance of Project Management. 2nd edition. Pa: APM

- ↑ E.G. Too, P. Weaver. The management of project management: A conceptual framework for project governance. International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) p.1382–1394

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 P.S. Renz. Project Governance - Implementing Corporate Governance and Business Ethics in Nonprofit Organizations. Springer (2007)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 C. Biesenthal & R. Wilden. Multi Level Project Governance: Trends and Opportunities. 2014

- ↑ Project Management Institute. (2008). The standard for Program Management. Newtown Square, Pa: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Project Management Institute. (2008). The standard for Portfolio Management. Newtown Square, Pa: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ B.M. Mitnick. (1973). Fiduciary rationality and public policy: The theory of agency and some consequences. Paper presented at the 1973 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, New Orleans, LA In Proceedings of the APSA, 1973

- ↑ O. Williamson, (1998). Transaction cost economics: how it works; where it is headed. De Economist 146, 23–58.

- ↑ Donaldson, T., Preston, L.E., 1995. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 65–91

- ↑ Pfeffer, J., Salancik, G.R., 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California

- ↑ Hung, H. (1998). A typology of the theories of the roles of governing boards. In: Scholarly research and theory papers. 6/2. April 1998. pp. 101 – 111.