Benchmarking in Project Management

(→Types of Benchmarking) |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Benchmarking has been characterized as a developing science and thus many generations can be identified [9]. As it can be seen in Figure 2 the first generation of benchmarking, called “Reverse Benchmarking”, was entirely focused on the comparisons based on products' characteristics, functionality and performance with similar products, and thus it was more product-oriented. | |

| − | + | ||

[[File: Benchmarking_as_a_developing_evaluation_tool.PNG|thumb|upright=4|Figure 2: Benchmarking as a developing evaluation tool]] | [[File: Benchmarking_as_a_developing_evaluation_tool.PNG|thumb|upright=4|Figure 2: Benchmarking as a developing evaluation tool]] | ||

| − | + | Furthermore, the second generation, or as called “Competitive Benchmarking”, involved comparisons of processes with those of the competitors. The “Process Benchmarking”, which was the third generation of benchmarking, suggested that comparisons were developed outside the same industry. Adding to that, evaluations mostly had targeted companies with recognized strong practices, regardless of the industry and the competitors. The fourth generation is referred as “Strategic Benchmarking”, and is a systematic process of alternatives assessment, implementation of strategies and improvement of performance by trying to understand and adapt to successful strategies that external partners who participate in an ongoing business alliance use. Strategic benchmarking is about trying to compare a competitor's strategy to one's own in the same market and product benchmarking compares the features and performance of actual products. Gattorna and Walters [10] argue that unless the strategic direction of the targeted benchmark company is understood, it is unlikely that the comparative exercise will prove successful, especially in the management strategies of projects. Management performance falls under performance benchmarking but is influenced by the company's strategies. Benchmarking project management is a subset within the managerial performance indicators. | |

| − | + | Watson sees future generations of benchmarking in global applications where business process distinctions among companies are bridged and their implications for business process improvements are understood. In this era of global project management organisations, this generation of benchmarking should help such organisations identify and link with the best in class. | |

| − | + | The fifth generation or “Global Benchmarking” has to do with a global development and application of benchmarking, and thus is dealing with the globalization of industries [11]. This generation of benchmarking is helping organisations to identify which are the best in class and then and link with them. Some extensions of the model are beginning to emerge as Kyro [12] claims to foresee a sixth and seventh generation called “benchlearning” and “network benchmarking” respectively. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | The | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | Watson sees future generations of benchmarking in global applications where business process distinctions among companies are bridged and their implications for business process improvements are understood. In this era of global project management organisations, this generation of benchmarking should help such | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | This | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

==Benchmarking in Project management== | ==Benchmarking in Project management== | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 19 September 2015

Nowadays, project management tools and methodologies have been highly useful for organisations that seek to implement changes in order to increase their performance. Adding to that, organisations are constantly striving to find new opportunities to make it as much effective for them as possible. One of these opportunities is to examine the outcomes and the lessons learnt from various similar projects that have been completed in the market from similar organisations and thus use benchmarking.

As a business term, benchmarking is the series of actions in order to compare one's business distinct processes, practices or procedures, to other businesses that perform similar activities and have a leading role in the world market. Benchmarking is mainly used so that the company gains valuable information in pursuance of improving its performance and, as a natural outcome, to increase its competitiveness. Usually, there are different indicators that companies use to assess their performance during the process of benchmarking that mainly focus on the aspects of time, cost and quality.

It has been proved that benchmarking against companies that have a leading role in the industry has effectively helped average organizations to improve their performance [2]. Based on that, this article will present how improvements in the performance of companies can be achieved by benchmarking projects. This article will firstly explore the general purpose of benchmarking. Then, it will be examined how the distinct types of benchmarking can be applied to the management of projects. Furthemore, there will be a discussion on what to benchmark and what aptitudes are needed to do so. Finally, an analysis about the limitations of benchmarking in project management will be held.

Contents |

Purpose of Benchmarking

Benchmarking is a constant process of analysis and research of the best performers in order to extrude useful information for improving the organisational or project performance of a company, and not just copy or imitate what others do to thrive. As Bent and Humphrey suggest about benchmarking, ‘‘Benchmarking is the technical core of the Total Quality Management (TQM) process. It identifies the quality of current personal skill levels and company procedures/methods, and then compares this quality with the latest state-of-the-art techniques’’ [3].

Another definition of benchmarking was suggested from the International Benchmarking Clearinghouse (IBC) Design Steering Committee which concluded in 1992 that benchmarking is: “A systematic and continuous measurement process; a process of continuously measuring and comparing an organisation’s business processes against business process leaders anywhere in the world to gain information which will help the organisation take action to improve its performance [4].”

It is clear from these definitions that benchmarking is not only a process in which performance, compared to others, can be measured, but also a tool to describe how notable performance can be accomplished. This kind of performance can be described by measures of performance indicators, called benchmarks. The activities that are used in order to achieve this performance are called enablers [5] and their main purpose is to analyze the logic for achieving this kind of notable performance. Usually, benchmarking studies are conducted with the support of this two components and thus it can be stated that benchmarks can be attained by obtaining enablers.

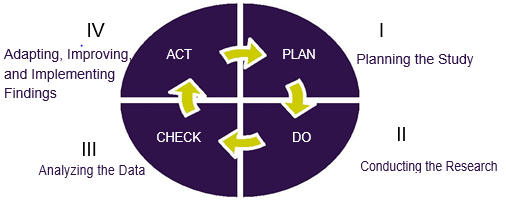

As part of the benchmarking process, many models and approaches have been used but they all take into account an iterative benchmarking process proposed by W.E Deming called the “Deming cycle”. The Deming cycle includes a minimum of four phases “Plan –Do-Action-Check” and is presented in Figure 1.

Types of Benchmarking

The types of benchmarking indicate what is compared when they involve comparisons that are closely associated with process, performance and strategic benchmarking. Apart from that, when they include internal, functional, generic and competitive comparisons, they are referred to whom it is compared against [7,8]. All these type of benchmarking are further analyzed in the table below.

| Types of Benchmarking | Definition |

|---|---|

| Performance Benchmarking | Comparison of performance measures in order to determine how good an organization is if compared to others. |

| Process Benchmarking | Comparison of methods and processes in order to improve the processes in an organization. |

| Strategic Benchmarking | Comparison of the current organization’s strategy with other successful strategies from organizations in the market.

This helps to improve competence so that the organization can cope with the changes in the external environment. |

| Internal Benchmarking | Comparisons of performance of departments inside the same organization in order to find and apply best practice information. |

| Competitive Benchmarking | Comparison made against the “best” competition inside the same to compare performance and results. |

| Functional Benchmarking | Comparisons regarding particular functions in an industry. The purpose is to master a specific function using this type of benchmarking |

| Generic Benchmarking | Comparison of processes against best process operators regardless the type of industry. |

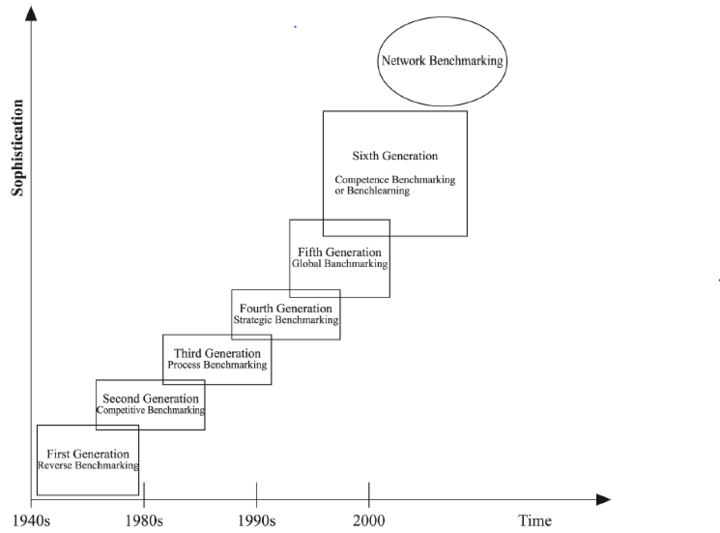

Benchmarking has been characterized as a developing science and thus many generations can be identified [9]. As it can be seen in Figure 2 the first generation of benchmarking, called “Reverse Benchmarking”, was entirely focused on the comparisons based on products' characteristics, functionality and performance with similar products, and thus it was more product-oriented.

Furthermore, the second generation, or as called “Competitive Benchmarking”, involved comparisons of processes with those of the competitors. The “Process Benchmarking”, which was the third generation of benchmarking, suggested that comparisons were developed outside the same industry. Adding to that, evaluations mostly had targeted companies with recognized strong practices, regardless of the industry and the competitors. The fourth generation is referred as “Strategic Benchmarking”, and is a systematic process of alternatives assessment, implementation of strategies and improvement of performance by trying to understand and adapt to successful strategies that external partners who participate in an ongoing business alliance use. Strategic benchmarking is about trying to compare a competitor's strategy to one's own in the same market and product benchmarking compares the features and performance of actual products. Gattorna and Walters [10] argue that unless the strategic direction of the targeted benchmark company is understood, it is unlikely that the comparative exercise will prove successful, especially in the management strategies of projects. Management performance falls under performance benchmarking but is influenced by the company's strategies. Benchmarking project management is a subset within the managerial performance indicators. Watson sees future generations of benchmarking in global applications where business process distinctions among companies are bridged and their implications for business process improvements are understood. In this era of global project management organisations, this generation of benchmarking should help such organisations identify and link with the best in class. The fifth generation or “Global Benchmarking” has to do with a global development and application of benchmarking, and thus is dealing with the globalization of industries [11]. This generation of benchmarking is helping organisations to identify which are the best in class and then and link with them. Some extensions of the model are beginning to emerge as Kyro [12] claims to foresee a sixth and seventh generation called “benchlearning” and “network benchmarking” respectively.