BCG Matrix in Portfolio Management

(→Categorization of businesses into four distinct portfolio groups) |

(→Comparison to other matrices) |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

= Abstract = | = Abstract = | ||

| − | ''' | + | The '''growth share matrix''', also known as the product portfolio matrix or Boston Consulting Group matrix, was developed through the collaborative efforts of BCG partners. Alan Zakon initiated the concept and subsequently refined it with his colleagues. BCG's founder, Bruce D. Henderson, popularized the matrix in his essay titled "The Product Portfolio" published in BCG's Perspectives in 1970 <ref> [''BCG History''] https://www.bcg.com/about/overview/our-history/growth-share-matrix </ref>. |

| − | The | + | |

| − | This article will | + | The matrix serves as a tool to aid organizations and businesses in analysing their product/services portfolio <ref> [''PMI Standards''] https://www.pmi.org/ </ref>, enabling them to allocate resources effectively. It is commonly used as an analytical tool in strategic management, brand marketing, product management, and portfolio analysis. |

| + | |||

| + | This article will provide a comprehensive explanation of each component of the matrix and its significance, accompanied by a pertinent study case as an example. Additionally, a critical assessment of the matrix will be presented by examining its strengths, appropriate use, limitations, and misuses in the industry. Lastly, a comparison will be made between this matrix and other comparable matrices employed in portfolio management, such as the McKinsey matrix. | ||

= The fundamental elements and underlying assumptions of BCG Matrix = | = The fundamental elements and underlying assumptions of BCG Matrix = | ||

| − | The BCG Matrix evaluates a company's product portfolio | + | The BCG Matrix evaluates a company's product portfolio through an evaluation of the relative strength of each business product and the growth rate of its associated market or industry. This analytical approach yields a comprehensive analysis of the company's product portfolio, which facilitates informed decision-making. Furthermore, the BCG Matrix has the capacity to communicate corporate decisions to subsidiary companies. Henderson, in his commentary on the Matrix at the time of its creation, stated:<ref> [''Henderson, Bruce D. (1970). The Experience Curve - Reviewed IV. The Growth Share Matrix or The Product Portfolio''] </ref>: |

<blockquote> ''"Such a single chart with a projected position five years out is sufficient alone to tell a company's profitability, debt capacity, growth potential, dividend potential and competitive strength".'' </blockquote>. | <blockquote> ''"Such a single chart with a projected position five years out is sufficient alone to tell a company's profitability, debt capacity, growth potential, dividend potential and competitive strength".'' </blockquote>. | ||

=== Categorization of businesses into four distinct portfolio groups === | === Categorization of businesses into four distinct portfolio groups === | ||

[[File:BCG-Matrix-5.png|500px|thumb|right|Figure 1. - BCG-Matrix with growth/share axis and the four portfolio categories.]] | [[File:BCG-Matrix-5.png|500px|thumb|right|Figure 1. - BCG-Matrix with growth/share axis and the four portfolio categories.]] | ||

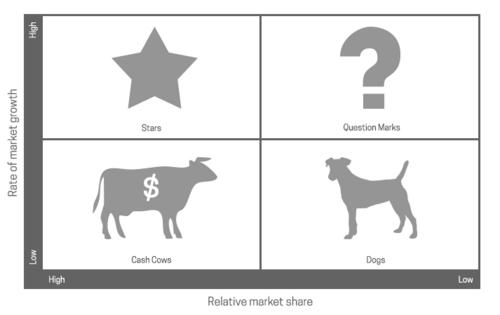

| − | The | + | The Matrix is partitioned into four quadrants, each highlighting a distinct type of business unit: cash cows, dogs, question marks, and stars. To evaluate the business products in a portfolio, the BCG Matrix necessitates the use of a scatter graph with metrics like market share and growth rate. This approach enables analysts to appraise the overall product portfolio of the company. By visually representing the units, the Matrix identifies the units that are performing well and those that require attention. |

| − | To | + | |

#'''Cash cows''' | #'''Cash cows''' | ||

| − | #:Cash cows | + | #:Cash cows denote to products that hold a supreme position in a mature industry and yield significant profits for the company. These products are meant to be "milked" with minimal investment since the industry's growth is slow. |

#'''Dogs''' | #'''Dogs''' | ||

| − | #: | + | #:Dogs, also called sometimes as pets, refer to products with a significant market share in a mature industry. These products generate just enough revenue to compete and break-even. |

#'''Question marks''' | #'''Question marks''' | ||

| − | #:Question marks | + | #:Question marks refer to products with a low market share in a developing market, serving as a starting point for most companies. Question marks has the potential to gain market share and become stars, eventually transitioning to cash cows when the market growth slows down. If question marks don't succeed in becoming a market leader, they will turn into dogs. |

#'''Stars''' | #'''Stars''' | ||

| − | #:Stars | + | #:Stars denote products with a leading market share in a developing industry. They are previously question marks with an established market share. |

| − | The underlying | + | The fundamental assumption underlying the BCG Matrix is that market growth and investment opportunities are inherently interconnected. As a market expands, it presents a potentially lucrative avenue for investment, as the funds allocated to it have the potential to compound over time and yield greater returns in the future. However, as a market grows, the need for cash to maintain market share and competitive position increases as well, lest products become dogs due to low relative market share. In the BCG Matrix, market growth is the primary driver of market attractiveness. |

=== Product life cycle === | === Product life cycle === | ||

| − | The | + | The BCG Matrix segments can be related to the different stages of the product life cycle. Question marks represent products in the introduction phase, with high costs and low sales and profits. Investment strategies are needed to increase market share in a growing market. Successful management leads to the growth phase and profitability increases. However, increased competition may cause price decreases and reduce profits. In the maturity stage, the highest relative market share provides a significant advantage, and the company can harvest profits due to the experience curve effect. These products are the cash cows. In the saturation and decline stage, sales and profits decrease, and the market becomes unattractive, leading to divestment strategies, similar to how dogs are treated. |

=== Matrix best practices === | === Matrix best practices === | ||

| − | + | To enhance the representation of business units on the Matrix, a portfolio analysis is conducted, which evaluates various Strategic Business Units (SBUs) <ref> [''Strategic business unit''] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategic_business_unit </ref> and their corresponding product markets. SBUs are businesses that concentrate on a specific combination of products and markets, and they need some degree of autonomy while sharing similar resources and structures. This allows each SBU to make autonomous decisions without affecting other units in the portfolio. However, determining SBUs can be challenging because products within an SBU may have differing market growth rates and relative market shares. The Matrix represents the relative importance of each SBU by scaling the size of a circle proportionally to either sales or assets. <ref> [''Hedley, Barry (1977). Strategy and the "Business Portfolio", p. 9-15''] </ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

=== Relative Market Share === | === Relative Market Share === | ||

| − | + | The experience curve concept introduced by Henderson in 1968 <ref> [''Strategic business unit''] https://www.bcg.com/publications/1968/business-unit-strategy-growth-experience-curve </ref> suggests that the company with the highest market share is likely to have the most substantial profit margin. This is because a company's relative position compared to its competitors is a critical factor in determining its profitability, with a stronger position typically leading to higher profits. To determine a company's competitive position, the most fundamental measure is relative market share, which is calculated by dividing the business's market share by its largest competitor's share. Thus, a higher relative market share indicates greater potential for cash generation by the company. | |

= The aim of the matrix in decision making = | = The aim of the matrix in decision making = | ||

| − | The | + | The BCG-Matrix is centred around maintaining a balance of positive and negative cash flows across various businesses. It categorizes each quadrant as a net cash generator or cash user, making assumptions about the cash position of each quadrant critical to the concept's effectiveness. According to the matrix, companies should seek to have "stars" with high market share and growth to secure the company's future. "Cash cows" are also essential to provide capital for future investments and cover current expenses. A selected range of "question marks" is necessary since they can potentially transform into "stars" with some investment influx. On the other hand, "dogs" indicate failure and should be liquidated. <ref> [''The Growth Share Matrix''] https://www.bcg.com/publications/2014/growth-share-matrix-bcg-classics-revisited </ref> |

= Case study = | = Case study = | ||

[[File:case example.png|500px|thumb|right|Figure 2. - Initial business portfolio of exemplary cases.]] | [[File:case example.png|500px|thumb|right|Figure 2. - Initial business portfolio of exemplary cases.]] | ||

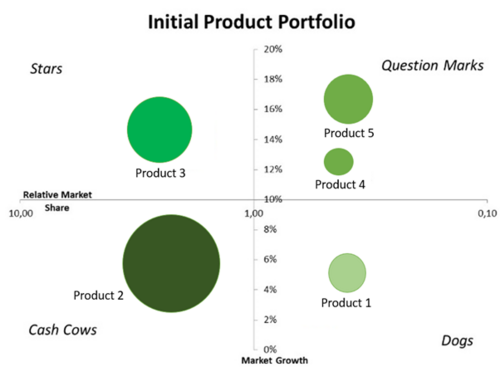

| − | + | While the matrix provides a straightforward and visual way to analyse business units, it does require certain elements to be carefully considered. In order to showcase the matrix's effectiveness in guiding strategic decisions, a case study will be presented and extensively examined. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | For the horizontal axis | + | Although we have already covered the main quadrants of the BCG-Matrix, it is crucial to pay close attention to the scaling of axes and the placement of the horizontal and vertical dividing lines that divide the matrix into four quadrants. The vertical axis, representing growth rate, is measured on a continuous scale, and some sources recommend setting the dividing line at the anticipated inflation-adjusted growth in gross national income (GNI). This is important for ensuring that the matrix accurately reflects the business's position in relation to the overall market and that strategic decisions are based on sound data. However, Henderson and Hedley proposed a 10% growth rate as the dividing line, which is the typical discount rate used by companies during times of low inflation. Any growth above this rate is deemed attractive for investment. Accurate scaling of the vertical axis is necessary to ensure that a business is appropriately categorized as a star, cash cow, dog, or question mark. |

| + | |||

| + | For the horizontal axis, which represents relative market share, should be on a logarithmic scale, with the dividing line set at [1,0], as only the relative market share of the largest competitor can be left of this line, with all others falling below this value by definition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These guidelines are not absolute and may require adaptations to achieve accurate results and make appropriate strategic decisions for the business portfolio. Once the matrix is constructed and the quadrants are defined, each SBU or product can be plotted within it based on its sales or assets relevance. | ||

=== Assumptions === | === Assumptions === | ||

| − | Assuming | + | Assuming a hypothetical company's portfolio is represented in the matrix depicted in the figure below, which shows multiple business units and their corresponding quadrant assignments. The size of the circle represents the total sales volume of each unit. The portfolio comprises a strong cash cow product 2 and a promising star product 3, along with a few question marks (product 4 and 5) and a dog (product 1). It is crucial to note that each business requires unique strategic goals to make the most of opportunities. It would be a mistake to prescribe a single, overarching goal for all businesses, as each business unit has its own unique characteristics that require careful evaluation to determine the appropriate strategic implications. |

The management strategic decisions therefore would be: | The management strategic decisions therefore would be: | ||

| Line 58: | Line 61: | ||

[[File:Success_seq.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Figure 3. - Success Sequence.]] | [[File:Success_seq.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Figure 3. - Success Sequence.]] | ||

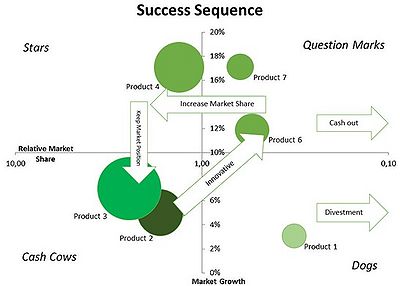

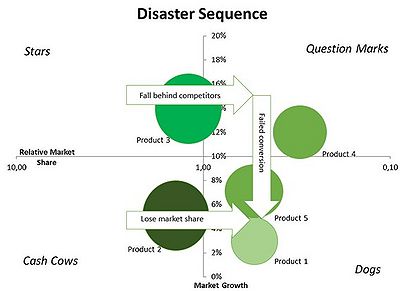

| − | + | Investing in all question marks without proper evaluation may lead to a lack of resources, resulting in a "sequence of disaster." Therefore, it is crucial to invest in only a few promising question marks and divest the rest. This will lead to a "success sequence" where the selected question marks generate future net cash flow. The following figures illustrate the performance of a company over a three-year period under both scenarios; Success Sequence and Disaster Sequence. It is important to note that the strategic implications of the BCG-Matrix are specific to each business unit, and a one-size-fits-all approach should be avoided. The two scenarios can be summarized as follows: | |

[[File:Disaster_seq.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Figure 4. - Disaster sequence.]] | [[File:Disaster_seq.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Figure 4. - Disaster sequence.]] | ||

| Line 70: | Line 73: | ||

— Bruce Henderson, “The Product Portfolio,” 1970. | — Bruce Henderson, “The Product Portfolio,” 1970. | ||

| − | + | The BCG matrix has several advantages, including its simplicity and ability to provide a clear framework for analysing a company's product portfolio. It presents an intuitive visual representation of the portfolio and enables businesses to recognize areas that require resource allocation, as well as areas that can generate revenue without substantial investment. Additionally, the matrix aids in identifying products that may no longer align with the company's goals and may need to be divested or discontinued. | |

| − | However, | + | However, while it is valuable, it has indeed several drawbacks. Firstly, the matrix's reliance on market share and growth overlooks other critical variables such as customer demand and competitive pressure. Secondly, the matrix assumes that high market share and growth are always favourable, which may not be the case. Finally, the matrix is static and fails to consider shifts in the market over time. Although products may shift between categories over time, the matrix does not account for this. |

| − | Despite its theoretical usefulness and widespread use, the efficacy of the growth-share matrix in contributing to business success has been investigated by several academic studies, resulting in its removal from some significant marketing textbooks. In 1992, a study was conducted by Slater and Zwirlein where they examined 129 firms that used the BCG matrix in their portfolio planning models. The study has shown that those firms tend to have lower shareholder returns. Furthermore, the BCG matrix has been criticized on several other grounds. For instance, it categorizes dogs as entities with low market share and relatively low market growth rate. | + | Despite its theoretical usefulness and widespread use, the efficacy of the growth-share matrix in contributing to business success has been investigated by several academic studies, resulting in its removal from some significant marketing textbooks <ref> [''An Analysis on BCG Growth Sharing Matrix''] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322695566_An_Analysis_on_BCG_Growth_Sharing_Matrix </ref>. In 1992, a study was conducted by Slater and Zwirlein where they examined 129 firms that used the BCG matrix in their portfolio planning models. The study has shown that those firms tend to have lower shareholder returns. Furthermore, the BCG matrix has been criticized on several other grounds. For instance, it categorizes dogs as entities with low market share and relatively low market growth rate. |

= Comparison to other matrices = | = Comparison to other matrices = | ||

| Line 80: | Line 83: | ||

Alternatively, there are several methods in portfolio management that can offer a similar view on the growth share of a company. The most widely used method is developed by McKinsey and it is called – you guessed it, McKinsey matrix, also known as the directional policy matrix. | Alternatively, there are several methods in portfolio management that can offer a similar view on the growth share of a company. The most widely used method is developed by McKinsey and it is called – you guessed it, McKinsey matrix, also known as the directional policy matrix. | ||

| − | McKinsey matrix | + | McKinsey matrix categorizes business organizations into those with good prospects and those with less good prospects <ref> [''The Directional Policy Matrix'']https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-13877-7_26#:~:text=The%20Directional%20Policy%20Matrix%20(DPM,perceives%20markets%20to%20be%20attractive. </ref>. It places business organizations according to two aspects: |

| − | - | + | - How attractive the relevant market is in which they are operating |

| − | - | + | - The competitive strength of the strategic business unit in that market. |

| − | The attractiveness can be measured by PESTEL or five forces analyses, while business unit strength can be | + | The attractiveness can be measured by PESTEL or five forces analyses, while business unit strength can be determined through competitor analysis (such as the strategy canvas). Managers of this organization may be concerned about their relatively low market shares in the largest and most attractive market, while their greatest strength lies in a market with only moderate attractiveness and smaller markets with little long-term potential. |

| − | The matrix | + | The directional policy matrix provides recommendations for business unit placement based on strategy. It advises investing in businesses with the most potential for growth and the highest strength, while divesting or "harvesting" those in unattractive markets or with lower strength. Compared to the BCG matrix, the directional policy matrix is more intricate, but it has two potential advantages. First, it recognizes the possibility of a challenging middle ground that the four-box BCG matrix does not. Second, it includes nine cells, offering a more detailed analysis. |

== Annotated bibliography == | == Annotated bibliography == | ||

| + | <ref> [''Henderson, Bruce D. (1970). The Experience Curve - Reviewed IV. The Growth Share Matrix or The Product Portfolio''] </ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Henderson, Bruce D. (1970). The Experience Curve - Reviewed IV. The Growth Share Matrix or The Product Portfolio ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | This article by Bruce D. Henderson, published in the Boston Consulting Group's journal in 1970, focuses on the relationship between the Experience Curve and the Growth Share Matrix, also known as the Product Portfolio. The article provides a comprehensive review of the Growth Share Matrix, discussing its origin, purpose, and application. Henderson emphasizes the importance of the Experience Curve in understanding the growth potential and profitability of a company's products. The Experience Curve theory suggests that as a company gains experience in producing a particular product, its costs decrease and efficiency improves, resulting in a decrease in the product's per-unit cost over time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref> [''Hedley, Barry (1977). Strategy and the "Business Portfolio", p. 9-15''] </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Hedley, Barry (1977). Strategy and the "Business Portfolio", p. 9-15''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The article highlights the importance of strategic fit and synergy within the business portfolio. Hedley explains that a portfolio should consist of complementary business units that can leverage each other's strengths and create synergistic effects. This strategic fit enables businesses to optimize their resource allocation, reduce redundancies, and enhance overall competitiveness. The author emphasizes that portfolio analysis should be an ongoing process, with regular reassessment of the business units' performance and alignment with strategic objectives. Hedley also highlights the dynamic nature of the business environment and the need for flexibility in portfolio management. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref> [''The Directional Policy Matrix'']https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-13877-7_26#:~:text=The%20Directional%20Policy%20Matrix%20(DPM,perceives%20markets%20to%20be%20attractive. </ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''The Directional Policy Matrix''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Directional Policy Matrix (DPM) is a strategic framework used to classify and categorize an organization's business activities based on its strengths, capabilities, market position, and perceived market attractiveness. The DPM provides a structured way to analyze an organization's portfolio of products or areas of operation. This framework enables organizations to conduct a comprehensive analysis of their business activities, assess the strengths and weaknesses of their product offerings, and identify opportunities for growth or necessary strategic adjustments. By considering the relative strength of their offerings and the attractiveness of the markets they operate in, organizations can allocate resources, prioritize investments, and develop appropriate strategies to maximize their competitive advantage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 11:38, 8 May 2023

Contents |

[edit] Abstract

The growth share matrix, also known as the product portfolio matrix or Boston Consulting Group matrix, was developed through the collaborative efforts of BCG partners. Alan Zakon initiated the concept and subsequently refined it with his colleagues. BCG's founder, Bruce D. Henderson, popularized the matrix in his essay titled "The Product Portfolio" published in BCG's Perspectives in 1970 [1].

The matrix serves as a tool to aid organizations and businesses in analysing their product/services portfolio [2], enabling them to allocate resources effectively. It is commonly used as an analytical tool in strategic management, brand marketing, product management, and portfolio analysis.

This article will provide a comprehensive explanation of each component of the matrix and its significance, accompanied by a pertinent study case as an example. Additionally, a critical assessment of the matrix will be presented by examining its strengths, appropriate use, limitations, and misuses in the industry. Lastly, a comparison will be made between this matrix and other comparable matrices employed in portfolio management, such as the McKinsey matrix.

[edit] The fundamental elements and underlying assumptions of BCG Matrix

The BCG Matrix evaluates a company's product portfolio through an evaluation of the relative strength of each business product and the growth rate of its associated market or industry. This analytical approach yields a comprehensive analysis of the company's product portfolio, which facilitates informed decision-making. Furthermore, the BCG Matrix has the capacity to communicate corporate decisions to subsidiary companies. Henderson, in his commentary on the Matrix at the time of its creation, stated:[3]:

"Such a single chart with a projected position five years out is sufficient alone to tell a company's profitability, debt capacity, growth potential, dividend potential and competitive strength"..

[edit] Categorization of businesses into four distinct portfolio groups

The Matrix is partitioned into four quadrants, each highlighting a distinct type of business unit: cash cows, dogs, question marks, and stars. To evaluate the business products in a portfolio, the BCG Matrix necessitates the use of a scatter graph with metrics like market share and growth rate. This approach enables analysts to appraise the overall product portfolio of the company. By visually representing the units, the Matrix identifies the units that are performing well and those that require attention.

- Cash cows

- Cash cows denote to products that hold a supreme position in a mature industry and yield significant profits for the company. These products are meant to be "milked" with minimal investment since the industry's growth is slow.

- Dogs

- Dogs, also called sometimes as pets, refer to products with a significant market share in a mature industry. These products generate just enough revenue to compete and break-even.

- Question marks

- Question marks refer to products with a low market share in a developing market, serving as a starting point for most companies. Question marks has the potential to gain market share and become stars, eventually transitioning to cash cows when the market growth slows down. If question marks don't succeed in becoming a market leader, they will turn into dogs.

- Stars

- Stars denote products with a leading market share in a developing industry. They are previously question marks with an established market share.

The fundamental assumption underlying the BCG Matrix is that market growth and investment opportunities are inherently interconnected. As a market expands, it presents a potentially lucrative avenue for investment, as the funds allocated to it have the potential to compound over time and yield greater returns in the future. However, as a market grows, the need for cash to maintain market share and competitive position increases as well, lest products become dogs due to low relative market share. In the BCG Matrix, market growth is the primary driver of market attractiveness.

[edit] Product life cycle

The BCG Matrix segments can be related to the different stages of the product life cycle. Question marks represent products in the introduction phase, with high costs and low sales and profits. Investment strategies are needed to increase market share in a growing market. Successful management leads to the growth phase and profitability increases. However, increased competition may cause price decreases and reduce profits. In the maturity stage, the highest relative market share provides a significant advantage, and the company can harvest profits due to the experience curve effect. These products are the cash cows. In the saturation and decline stage, sales and profits decrease, and the market becomes unattractive, leading to divestment strategies, similar to how dogs are treated.

[edit] Matrix best practices

To enhance the representation of business units on the Matrix, a portfolio analysis is conducted, which evaluates various Strategic Business Units (SBUs) [4] and their corresponding product markets. SBUs are businesses that concentrate on a specific combination of products and markets, and they need some degree of autonomy while sharing similar resources and structures. This allows each SBU to make autonomous decisions without affecting other units in the portfolio. However, determining SBUs can be challenging because products within an SBU may have differing market growth rates and relative market shares. The Matrix represents the relative importance of each SBU by scaling the size of a circle proportionally to either sales or assets. [5]

[edit]

The experience curve concept introduced by Henderson in 1968 [6] suggests that the company with the highest market share is likely to have the most substantial profit margin. This is because a company's relative position compared to its competitors is a critical factor in determining its profitability, with a stronger position typically leading to higher profits. To determine a company's competitive position, the most fundamental measure is relative market share, which is calculated by dividing the business's market share by its largest competitor's share. Thus, a higher relative market share indicates greater potential for cash generation by the company.

[edit] The aim of the matrix in decision making

The BCG-Matrix is centred around maintaining a balance of positive and negative cash flows across various businesses. It categorizes each quadrant as a net cash generator or cash user, making assumptions about the cash position of each quadrant critical to the concept's effectiveness. According to the matrix, companies should seek to have "stars" with high market share and growth to secure the company's future. "Cash cows" are also essential to provide capital for future investments and cover current expenses. A selected range of "question marks" is necessary since they can potentially transform into "stars" with some investment influx. On the other hand, "dogs" indicate failure and should be liquidated. [7]

[edit] Case study

While the matrix provides a straightforward and visual way to analyse business units, it does require certain elements to be carefully considered. In order to showcase the matrix's effectiveness in guiding strategic decisions, a case study will be presented and extensively examined.

Although we have already covered the main quadrants of the BCG-Matrix, it is crucial to pay close attention to the scaling of axes and the placement of the horizontal and vertical dividing lines that divide the matrix into four quadrants. The vertical axis, representing growth rate, is measured on a continuous scale, and some sources recommend setting the dividing line at the anticipated inflation-adjusted growth in gross national income (GNI). This is important for ensuring that the matrix accurately reflects the business's position in relation to the overall market and that strategic decisions are based on sound data. However, Henderson and Hedley proposed a 10% growth rate as the dividing line, which is the typical discount rate used by companies during times of low inflation. Any growth above this rate is deemed attractive for investment. Accurate scaling of the vertical axis is necessary to ensure that a business is appropriately categorized as a star, cash cow, dog, or question mark.

For the horizontal axis, which represents relative market share, should be on a logarithmic scale, with the dividing line set at [1,0], as only the relative market share of the largest competitor can be left of this line, with all others falling below this value by definition.

These guidelines are not absolute and may require adaptations to achieve accurate results and make appropriate strategic decisions for the business portfolio. Once the matrix is constructed and the quadrants are defined, each SBU or product can be plotted within it based on its sales or assets relevance.

[edit] Assumptions

Assuming a hypothetical company's portfolio is represented in the matrix depicted in the figure below, which shows multiple business units and their corresponding quadrant assignments. The size of the circle represents the total sales volume of each unit. The portfolio comprises a strong cash cow product 2 and a promising star product 3, along with a few question marks (product 4 and 5) and a dog (product 1). It is crucial to note that each business requires unique strategic goals to make the most of opportunities. It would be a mistake to prescribe a single, overarching goal for all businesses, as each business unit has its own unique characteristics that require careful evaluation to determine the appropriate strategic implications.

The management strategic decisions therefore would be:

- Cash cows: Maintain, since they currently generate profitability.

- Dogs: Expected to generate some profits, but may be divested soon.

- Stars: Keep, hoping to expand its current market share.

- Question marks: Invest in some to gain market share and sell others for cash.

[edit] Scenarios

Investing in all question marks without proper evaluation may lead to a lack of resources, resulting in a "sequence of disaster." Therefore, it is crucial to invest in only a few promising question marks and divest the rest. This will lead to a "success sequence" where the selected question marks generate future net cash flow. The following figures illustrate the performance of a company over a three-year period under both scenarios; Success Sequence and Disaster Sequence. It is important to note that the strategic implications of the BCG-Matrix are specific to each business unit, and a one-size-fits-all approach should be avoided. The two scenarios can be summarized as follows:

- The company made "the best" decisions in managing its business portfolio in the Success sequence. First, the cash cow, Product 2, provided enough funds to develop Product 3, a former star, into a strong market leader. Despite the market slowing, Product 3 capitalized on its market position and became a cash cow, contributing more to total sales than Product 2. Concerning the question marks, the company pursued two approaches. Product 5 demonstrated promise but required significant investment, so it was sold for a good price and is no longer in the portfolio. While product 4 was developed with significant cash investment and became the company's new star. Despite a slowing in market growth, product 4 increased its market share significantly. The company had enough funds to innovate and develop new question marks, products 6 and 7, through the cash out of product 5 and the positive cash flow from the cash cows. However, the company could not sell product 1, which was a dog, so investment was reduced to allow for a slow death without compromising future success of the company.

- On the other hand, the Disaster Sequence, the company distributed investments equally among all its products instead of developing customized strategies for each. This ultimately result poor management and a decline in market share for product 2 (cash cow), leading to less net return for the company. Furthermore, product 3 (star) lost market share due to aggressive competition and may soon become a dog if immediate action is not taken. The company's inability to commit to a clear strategy also affected products 4 and 5 (former question marks), which failed to convert into stars despite receiving investment funds, draining the company's resources without providing any returns. In addition, the company invested in product 1 (dog), which continues to require more cash than it generates. With the market growth not expected to increase, the company's current leader is likely to maintain its strong position, making it difficult for product 1 to succeed.

[edit] Strengths and limitations

“A company should have a portfolio of products with different growth rates and different market shares. The portfolio composition is a function of the balance between cash flows.… Margins and cash generated are a function of market share.”

— Bruce Henderson, “The Product Portfolio,” 1970.

The BCG matrix has several advantages, including its simplicity and ability to provide a clear framework for analysing a company's product portfolio. It presents an intuitive visual representation of the portfolio and enables businesses to recognize areas that require resource allocation, as well as areas that can generate revenue without substantial investment. Additionally, the matrix aids in identifying products that may no longer align with the company's goals and may need to be divested or discontinued.

However, while it is valuable, it has indeed several drawbacks. Firstly, the matrix's reliance on market share and growth overlooks other critical variables such as customer demand and competitive pressure. Secondly, the matrix assumes that high market share and growth are always favourable, which may not be the case. Finally, the matrix is static and fails to consider shifts in the market over time. Although products may shift between categories over time, the matrix does not account for this.

Despite its theoretical usefulness and widespread use, the efficacy of the growth-share matrix in contributing to business success has been investigated by several academic studies, resulting in its removal from some significant marketing textbooks [8]. In 1992, a study was conducted by Slater and Zwirlein where they examined 129 firms that used the BCG matrix in their portfolio planning models. The study has shown that those firms tend to have lower shareholder returns. Furthermore, the BCG matrix has been criticized on several other grounds. For instance, it categorizes dogs as entities with low market share and relatively low market growth rate.

[edit] Comparison to other matrices

Alternatively, there are several methods in portfolio management that can offer a similar view on the growth share of a company. The most widely used method is developed by McKinsey and it is called – you guessed it, McKinsey matrix, also known as the directional policy matrix.

McKinsey matrix categorizes business organizations into those with good prospects and those with less good prospects [9]. It places business organizations according to two aspects:

- How attractive the relevant market is in which they are operating

- The competitive strength of the strategic business unit in that market.

The attractiveness can be measured by PESTEL or five forces analyses, while business unit strength can be determined through competitor analysis (such as the strategy canvas). Managers of this organization may be concerned about their relatively low market shares in the largest and most attractive market, while their greatest strength lies in a market with only moderate attractiveness and smaller markets with little long-term potential.

The directional policy matrix provides recommendations for business unit placement based on strategy. It advises investing in businesses with the most potential for growth and the highest strength, while divesting or "harvesting" those in unattractive markets or with lower strength. Compared to the BCG matrix, the directional policy matrix is more intricate, but it has two potential advantages. First, it recognizes the possibility of a challenging middle ground that the four-box BCG matrix does not. Second, it includes nine cells, offering a more detailed analysis.

[edit] Annotated bibliography

[10].

Henderson, Bruce D. (1970). The Experience Curve - Reviewed IV. The Growth Share Matrix or The Product Portfolio

This article by Bruce D. Henderson, published in the Boston Consulting Group's journal in 1970, focuses on the relationship between the Experience Curve and the Growth Share Matrix, also known as the Product Portfolio. The article provides a comprehensive review of the Growth Share Matrix, discussing its origin, purpose, and application. Henderson emphasizes the importance of the Experience Curve in understanding the growth potential and profitability of a company's products. The Experience Curve theory suggests that as a company gains experience in producing a particular product, its costs decrease and efficiency improves, resulting in a decrease in the product's per-unit cost over time.

Hedley, Barry (1977). Strategy and the "Business Portfolio", p. 9-15

The article highlights the importance of strategic fit and synergy within the business portfolio. Hedley explains that a portfolio should consist of complementary business units that can leverage each other's strengths and create synergistic effects. This strategic fit enables businesses to optimize their resource allocation, reduce redundancies, and enhance overall competitiveness. The author emphasizes that portfolio analysis should be an ongoing process, with regular reassessment of the business units' performance and alignment with strategic objectives. Hedley also highlights the dynamic nature of the business environment and the need for flexibility in portfolio management.

[12].

The Directional Policy Matrix

The Directional Policy Matrix (DPM) is a strategic framework used to classify and categorize an organization's business activities based on its strengths, capabilities, market position, and perceived market attractiveness. The DPM provides a structured way to analyze an organization's portfolio of products or areas of operation. This framework enables organizations to conduct a comprehensive analysis of their business activities, assess the strengths and weaknesses of their product offerings, and identify opportunities for growth or necessary strategic adjustments. By considering the relative strength of their offerings and the attractiveness of the markets they operate in, organizations can allocate resources, prioritize investments, and develop appropriate strategies to maximize their competitive advantage.

[edit] References

- ↑ [BCG History] https://www.bcg.com/about/overview/our-history/growth-share-matrix

- ↑ [PMI Standards] https://www.pmi.org/

- ↑ [Henderson, Bruce D. (1970). The Experience Curve - Reviewed IV. The Growth Share Matrix or The Product Portfolio]

- ↑ [Strategic business unit] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategic_business_unit

- ↑ [Hedley, Barry (1977). Strategy and the "Business Portfolio", p. 9-15]

- ↑ [Strategic business unit] https://www.bcg.com/publications/1968/business-unit-strategy-growth-experience-curve

- ↑ [The Growth Share Matrix] https://www.bcg.com/publications/2014/growth-share-matrix-bcg-classics-revisited

- ↑ [An Analysis on BCG Growth Sharing Matrix] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322695566_An_Analysis_on_BCG_Growth_Sharing_Matrix

- ↑ [The Directional Policy Matrix]https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-13877-7_26#:~:text=The%20Directional%20Policy%20Matrix%20(DPM,perceives%20markets%20to%20be%20attractive.

- ↑ [Henderson, Bruce D. (1970). The Experience Curve - Reviewed IV. The Growth Share Matrix or The Product Portfolio]

- ↑ [Hedley, Barry (1977). Strategy and the "Business Portfolio", p. 9-15]

- ↑ [The Directional Policy Matrix]https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-13877-7_26#:~:text=The%20Directional%20Policy%20Matrix%20(DPM,perceives%20markets%20to%20be%20attractive.