DMAIC Projects

(→SIPOC) |

(→Critical to Quality) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==== Critical to Quality ==== | ==== Critical to Quality ==== | ||

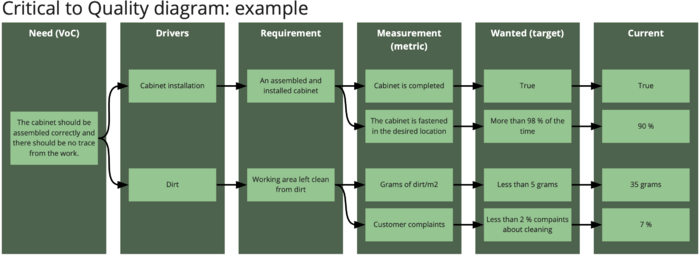

Following the VoC, the Critical to Quality (CTQ) is defined. Defining the CTQ means to describe what is necessary to fullfill the VoC. This requires an understanding why the VoC is a problem and what could remedy this. However, it does however not describe a specific solution. A well defined CTQ seeks to create a measureable target for an actual challenge of the VoC. For example, when the VoC is "The product keeps breaking, requirering me to return it", the CTQ could be "failure rate of products should be less than 95 % the first two years". This CTQ might be further updated later in the project, if for example a specific part is identified as the error source. However, as the VoC can also be more focused on user experience, the CTQ can also focus on this. By looking into the initial interviews and data, Drivers for specific CTQs can be identified. If the customer is mentions that a system might not work, says it always take a long time to complete a task or it is difficult to understand the messages, a CTQ could be to increase usability, measured by the amount of compaints. | Following the VoC, the Critical to Quality (CTQ) is defined. Defining the CTQ means to describe what is necessary to fullfill the VoC. This requires an understanding why the VoC is a problem and what could remedy this. However, it does however not describe a specific solution. A well defined CTQ seeks to create a measureable target for an actual challenge of the VoC. For example, when the VoC is "The product keeps breaking, requirering me to return it", the CTQ could be "failure rate of products should be less than 95 % the first two years". This CTQ might be further updated later in the project, if for example a specific part is identified as the error source. However, as the VoC can also be more focused on user experience, the CTQ can also focus on this. By looking into the initial interviews and data, Drivers for specific CTQs can be identified. If the customer is mentions that a system might not work, says it always take a long time to complete a task or it is difficult to understand the messages, a CTQ could be to increase usability, measured by the amount of compaints. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:CTQ_Example.png|700px|center|thumb|An example of a CTQ diagram.]] | ||

==== SIPOC ==== | ==== SIPOC ==== | ||

Revision as of 20:30, 13 March 2022

DMAIC is a project framework for working with Lean Six Sigma (LSS), which is based on both Six Sigma approach to systematic and quantitative approach to process improvements, and Lean [1]. A process following the Six Sigma approach aims to control the process in such a way, that no more than 3.4 defect per million possibilities, equal to all possibilities within 6 standard distributions (6σ). DMAIC is the framework used to work with process improvements, in order to reach the low failure rate. However, DMAIC can also be utilized to work towards other goals, such cycle time or customer satisfaction, as long as it is an existing process. [2].

DMAIC is an acronym for the five steps in the framework, called Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control. The five stages consist of:

- Define: in the define phase, what needs to be improved and for who is defined.

- Measure: the measure phase is used to further understand and document the problem

- Analyze: Based on the gathered data from the measure phase, the root causes to the problems are identified.

- Improve: With the root causes identified, a solution can now be developed, tested and pilot implemented.

- Control: The solution is first completely implemented in the important control phase. Following the implementation, it is paramount to monitor the effects, in order to ensure the change remains and works as intended.

This article describes the purpose, usage and limitations of using DMAIC in improvement projects. For creating a new process or radically changing an existing one, the DMADV framework is suggested instead.[1] DMAIC can fit a range of projects and while this article describes these, the application leans towards including product development and the qualitative users.

Contents |

The DMAIC Framework

DMAIC is a data driven project framework, with a strong quantitative basis, which is connected to explanatory qualitative data. This data driven approach aims to ensure the project is operating based on facts and provides value. The value of a DMAIC project can be in multiple different ways. There is a big focus on the customer and their requirements, which is determined in the beginning of the project in the Voice of Customer (VoC). DMAIC projects can be executed continuesly and repeatedly in order to perfect a process.

Between each phase of the DMAIC project, a gate meeting is held with the relevant stakeholders. During this meeting, the current results of the project is presented for the stakeholders. If the stakeholders find the current results and proposed forward direction adequete, the gate is agreed as open and the next phase can begin. This is much like the Stage-Gate Process. This is done to ensure the final solution can work for the stakeholders and gain additional insights through cross collaboration. Another important aspect in DMIAC is co-developing with the users. As a project manager, it is important to ensure this co-creation takes place, as it supports the four most important values in the project management community. These values are responsibility, respect, fairness, and honesty. [3] By succesfully implementing a co-creation process and the four mentioned values, there is a higher chance of succesfully creating a functional solution that also remains implemented.

DEFINE

The define phase aims to set the scene for the project. Identifying and understanding the customer is done by defining the Voice of Customer (VoC), followed by defining what is Critical to Quality (CTQ). Additionally, a SIPOC (Supplier, Input, Process, Output and Customer) analysis is often used to lay the project foundations. [4]

Voice of Customer

The VoC focus on the challenges of the customer, who can either be interal or external to the organisation. [5] There is often multiple stakeholders in the project and while defining the needs of the primary customer should be the focus of the VoC, it can benefit to also define VoC of the other stakeholders. This is to ensure the solution is optimal as possible. A complete definition of the VoC should describe the desired situation through more general descriptions and can include multiple desired results. There are multiple ways to define a corrent VoC, however the defined VoCs requires an understanding of the overall context, which can be gained through a small preliminary investigation, where key stakeholders are interviewed and relevant available data (for example customer surveys or error rates) is reviewed. A definition of a VoC can focus on an endless subject, so the following bullet points with examples should only serve as inspiration.

- We need our users to be better trained in The IT system is too difficult to use.

- The current manufacturing plant needs to produce more with the current hardware.

- The product keeps breaking, requirering me to return it.

Critical to Quality

Following the VoC, the Critical to Quality (CTQ) is defined. Defining the CTQ means to describe what is necessary to fullfill the VoC. This requires an understanding why the VoC is a problem and what could remedy this. However, it does however not describe a specific solution. A well defined CTQ seeks to create a measureable target for an actual challenge of the VoC. For example, when the VoC is "The product keeps breaking, requirering me to return it", the CTQ could be "failure rate of products should be less than 95 % the first two years". This CTQ might be further updated later in the project, if for example a specific part is identified as the error source. However, as the VoC can also be more focused on user experience, the CTQ can also focus on this. By looking into the initial interviews and data, Drivers for specific CTQs can be identified. If the customer is mentions that a system might not work, says it always take a long time to complete a task or it is difficult to understand the messages, a CTQ could be to increase usability, measured by the amount of compaints.

SIPOC

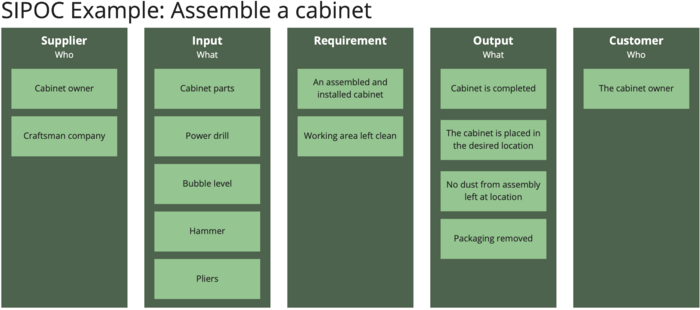

To further scope the project, a SIPOC diagram can be used to aggregate already gathered information, aswell as cover angles not yet explored. SIPOC is an acronym for supplier, input, process, output og customer. While the SIPOC diagram is structured like the anagram, it is filled out from the center to the right and then center to left. [1] The first step is therefore to map the process steps in the relevant process, which lays the foundations for the remaining fields. When completing the SIPOC, the goal should be to describe the process at a high-level with around 4-8 steps. Each sections contains the following: [6]

- Supplier: The entity executing the process, in order to provide the customer with the product or service. This is often a specific team member or team.

- Input: The necessary input required for the supplier to complete the Process.

- Process: The specific process step as identified in preparation for the SIPOC model, aiming to simply describe what happens.

- Output: This step should describe what has been achieved from the process.

- Customer: The customer should be seen as the person or entity recieving the Output.

MEASURE

The measure phase is focused on defining and documenting the current facts of the situation. This means gathering the facts necessary to properly understand the complete situation, context and most importantly the specific problem. In order to gather the correct data and ensure it is gathered consistently, a Data Collection Plan is developed. [2] It is advantagous to build the data collection plan based on the SIPOC, as the SIPOC provides an overview of the process. There is a wide range of types of data, which can be collected and while DMAIC is often focuses on quantitative data, qualitative data can be very usefull. Qualitative data can provide insights into areas where it can be beneficial to gather quantitative data, it can assist in the solution development and it can help in creating an understanding of why some data is as it is. The data which is going to be collected, should fit the type of project and associated goal. [2] Examples of quantitative data to collect can be; time consumption, error rate, units produced, but other types, such as customer satisfaction and employee morale can also be extremely relevant, again, depending on the context.

When it comes to collecting data, a range of sources should be considered. Some data can be gathered from existing data systems or simply by keeping count, while other types can benefit from evaluating video materials, completing questionaries, doing participant observations or alike. Data from participant observations or video material can often be quantified and thereby fit the DMAIC framework. The repeatability of the data collection is key to a succesfull DMAIC project. [2] This requires an accurate discription of the measuring method in order to keep the data consistent, even if a new person performs the measurements. This is especially relevant on data that requires human action to obtain. However, data from various systems should also be documented correct. If for example a temperature sensor is moved, the data will no longer be compareable.

ANALYSE

Following the Measure phase when the data collection is complete is the analyse phase, where the collected data has to be analyzed. Depending on the goal of the project, there are multiple ways of doing this. Simply visualizing the data through various diagrams can be a good starting point, as it gives an insight into areas that call for further analyzis or discover patterns. When experimenting with different types of visualizations, it is important to consider the VoC by for example grouping different types of data to understand what provides value and what does not. In order to further understand the connection between various quantitative data sets, statistical analysis should be utilized.

Ishikawa Diagram (Fishbone Diagram) and 7M's

A very used root cause analysis method is the Ishikawa Diagram, also known as the Fishbone diagram from its shape, wherein identified potential root causes and their influencers are structured.[2] This method can also combine quantitative data with qualitative data, as it can be combined in the diagram. The defined problem statement is noted at the end of the diagram, with each leg of the diagram respresenting a potential root cause category for why the problem exists. In each category, multiple influential factors can be attributed based on the collected data. [7] When the potential root causes are documented, the most likely root cause is selected for further work. If the root cause turns out not to be correct, one should return to the Ishikawa Diagram for further analysis.

A pre-structured version of an Ishikawa Diagram is often used to ensure the typical areas of root causes are considered. This model is called The 7M's and refers to the seven significant areas starting with M: Management, Mother Nature, Measurements, Materials, Manpower, Methods and Machines. As with the Ishikawa Diagram, potential root causes to the problem are listed at each M.

In connection with the Ishikawa Diagram, it should be considered which cause is most significant. When doing so, the overall VoC should be in focus, as other root causes might seem relevant, but does not affect the VoC significantly.

IMPROVE

The improve phase aims to reduce the waste and increase the value added through reducing costs and processing time, and improve service to the customer. [2] The possible solutions should be explored through Ideation tools, much like in the third Double diamond section called Develop.[1] Initial ideation methods include Brainstorming, ideation sketching and Worst Possible Idea. The improve phase can contain an iterative development sub process, where new developments are created, tested and evaluated a repeated number of times. The exact choice of iterative test cycle methodology can vary from organization to organization. One example of an iterative test cycle is described by Bjarki Hallgrimsson and contains four steps: [8]

- Ideate sketch: Initial ideas from for example brainstorming are visualized through quick sketches. The identified ideas can quickly be screened through an Impact effort matrix before proceeding to prototyping, still with a focus on the root cause and VoC.

- Build prototype: A few of the sketches are deemed as the ones with most potential and are prototyped. This step typically starts with very simple prototypes or even pretotypes, and then in later cycles move to more feature complete variants. It is important to note, that prototypes come in several different forms, from implementing physical ptotoypes to making process changes.

- Test and observe: The constructed pretotypes and prototypes have to be tested against their goals. As the goal of the DMIAC project is to solve the problems defined in the CTQ, the prototypes should also be tested against these.

- Identify improvements: Following the prototype testing, a range of potential lackings are most likely identified. These should be attempted to be solved through improvements to the prototype.

Another widely used improvement cycle is the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA).

CONTROL

The Control phase is paramount to ensuring the improvements stick. Despite this, it is often not as prioritized as the improvements are now seen as implemented and it is assumed it works as planned, as well as the costs associated with keeping the project open. [9] However, small adjustments are often needed to reach the optimal effects of the changes. While some of these changes are focused on the solution itself, it can also be simpler actions such as re-training employees, documenting the changes or defining Standard Operating Procedures. In order to discover a continued lack of control in the process after a change, a process monitoring tool should be utilized. An often used process monitoring tool in the Pareto analysis, also known as the 80/20 rule. In very statistically driven systems, it is recommended to utilize KPIs visualized on control charts. These control charts should have upper and lower limits where the process is considered in control between the values. If the process is no longer in control, the root cause should be investigated and mitigations should be implemented.

Limitations

A DMAIC project is quite comprehensive and therefore might not be suited for smaller improvement projects or simple problems. For smaller improvement projects, the A3 report might be better suited, as it contains a smaller selection of tools to solve simpler challenges. Utilizing DMAIC in practice can be a complex to succesfully do. [10] In order to effectively improve the project managers skills with Lean Six Sixgma, multiple certifications are developed. The most used Lean Six Sigma certifications levels are in accending order; Yellow Belt, Green Belt and Black Belt and Master Black Belt certifications. [2] While the belts indicate a persons expertice and experience with Lean Six Sigma, the requirements to reach these certifications vary from organization to organization and are therefore not universally applicable. [11]

Additionally, the comprehensiveness of DMAIC presents the risk of getting lost in the framework and ending up with a low creativity during the process. This can lead to selecting a solution, which might not be optimal. [12] The DMAIC framework requires a structured approach and benefits from an experienced project manager. Additionally, as DMAIC is a very broad framework, it can be adapted to the use case of a specific organization, project or problem. While the overall structure of the project still follows the five DMAIC phases, the specific methods selected and the use of the methods can vary significantly. Some systems such as manufacturing can have a lower focus on the qualitative details compared to a more product development focused entity.

When considering using DMAIC, it is important to note that DMAIC is not a system implementation framework. It is not ment to facilitate a project in simply implementing a new system. Other project management frameworks should be considered for this.

Annotated bibliography

LOST IN CO-X: INTERPRETATIONS OF CO-DESIGN AND CO-CREATION by Tuuli Mattelmäki and Froukje Sleeswijk Visser: When going through a DMAIC project, the user should be involved and a good way of doing this, is through Co-Creation. As co-creation is not discussed significantly in this wiki-article, it is suggested as further reading. Lost in CO-X gives an introduction to co-creation and co-design, thereby serving as a springboard for further readings about co-creation.

Lean Six Sigma 2nd edition by John Morgan and Martin Brenig-Jones: This book is one of the most important references of the wiki-article, and with good reason. It introduces Lean Six Sigma and DMAIC in a practical and reader-friendly form. Key concepts in each section are clealy marked and contains relevant examples. By including a comprehensive index, the book allows for quickly looking up methods or tool, thereby serving as a daily reference book.

The standard for project management. (2021):

The principles of project management and ethics. [3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Josefsen, R., Bækgaard, J., & Holme, K. S. (2014). Perfekte Processer. Praktisk Forlag.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Morgan, J., & Brenig-Jones, M. (2012). Lean six sigma for dummies: 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The standard for project management. (2021). A Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge (pmbok® Guide) – Seventh Edition and the Standard for Project Management (english) (pp. 21-60. Project Management Institute, Inc.

- ↑ 2022 House of Six Sigma https://houseofsixsigma.com/sipocen-et-undervurderet-vaerktoej

- ↑ 2021 International Six Sigma Institute https://web.archive.org/web/20220213113640/https://www.sixsigma-institute.org/Six_Sigma_DMAIC_Process_Define_Phase_Capturing_Voice_Of_Customer_VOC.php

- ↑ Kerri Simon. Retrieved on 3/3/2022. https://www.isixsigma.com/tools-templates/sipoc-copis/sipoc-diagram/ Archived on https://web.archive.org/web/20220125131744/https://www.isixsigma.com/tools-templates/sipoc-copis/sipoc-diagram/

- ↑ Matthew Barsalou. Retrieved 3/3/2022. https://www.isixsigma.com/tools-templates/cause-effect/root-cause-analysis-ishikawa-diagrams-and-the-5-whys/

- ↑ 2012. Bjarki Hallgrimsson. Prototyping and modelmaking for product design.

- ↑ Tim Williams. Case Study: Why a Team Cannot Afford to Overlook the C in DMAIC. https://www.isixsigma.com/new-to-six-sigma/dmaic/why-team-cannot-afford-overlook-c-dmaican-isixsigma-case-study/ Archived on https://web.archive.org/web/20210120030651/https://www.isixsigma.com/new-to-six-sigma/dmaic/why-team-cannot-afford-overlook-c-dmaican-isixsigma-case-study/

- ↑ T. M. Shahada and I. Alsyouf, "Design and implementation of a Lean Six Sigma framework for process improvement: A case study," 2012 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, 2012, pp. 80-84, doi: 10.1109/IEEM.2012.6837706.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DMAIC

- ↑ Expert Program Management. The DMAIC Model. https://expertprogrammanagement.com/2020/04/the-dmaic-model/