Groups or teams?

DarioFiorica (Talk | contribs) (→Limitation in teams: the Groupthink theory) |

DarioFiorica (Talk | contribs) (→Limitation in teams: the Groupthink theory) |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

[[File:Groupthink_image.png|600px|thumb|text-bottom|right|Figure 6: Overview of Groupthink. Adapted from <ref name="FromGtoT"/>]] | [[File:Groupthink_image.png|600px|thumb|text-bottom|right|Figure 6: Overview of Groupthink. Adapted from <ref name="FromGtoT"/>]] | ||

| − | Within teams, however, different issues can arise. One totally correlated to the cohesiveness and the consequent outcome (and performance) of the project is the “Groupthink” theory (Figure 5), first explained by Irving L. Janis in 1972 <ref name="JanGroupthink">''Groupthink: a revied and enlarged edition of Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes'', Irving L. Janis, Yale University, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 1972 </ref> as: “Quickly and easy way to refer to a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action”. In other words, Groupthink is the behaviour adopted by members of a moderately or high-cohesive team, to evaluate the cohesion of the team itself (showed as a collective pattern of thinking) more important than, instead, pragmatically analyze objective reality | + | |

| + | Within teams, however, different issues can arise. One totally correlated to the cohesiveness and the consequent outcome (and performance) of the project is the “Groupthink” theory (Figure 5), first explained by Irving L. Janis in 1972 <ref name="JanGroupthink">''Groupthink: a revied and enlarged edition of Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes'', Irving L. Janis, Yale University, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 1972 </ref> as: “Quickly and easy way to refer to a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action”. In other words, Groupthink is the behaviour adopted by members of a moderately or high-cohesive team, to evaluate the cohesion of the team itself (showed as a collective pattern of thinking) more important than, instead, pragmatically analyze objective reality<ref name="SD">''Groupthink: A Study in Self Delusion'', Christopher Booker, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020 </ref>, in this case regarding the project management context <ref name="MNBOOK"> ''Project Management Leadership: building creative teams'', Rory Burke, Steve Barron, 2nd edition, 2014 </ref>. Overall, the idea in which Janis’ framework is built around occurs when team demonstrates to be cohesive. Thus, the already existing antecedent conditions rise exponentially the probability that the team will show symptoms representative of Groupthink. In addition, the symptoms will lead to noticeable flaws in the team’s decision-making processes, and, consequently, to an impact in the final teams’ performance <ref name="FromGtoT">''From Groupthink to Teamthink: Toward the Creation of Constructive Thought Patterns in Self-Managing Work Teams'', Christopher P. Neck, Charles C. MAnz, 1994 </ref>. | ||

'''Antecedent conditions, Symptoms, and decision-making influence of Groupthink''' | '''Antecedent conditions, Symptoms, and decision-making influence of Groupthink''' | ||

Revision as of 14:52, 5 May 2023

Contents |

Abstract

In the complex practice of project management, the most important role is given to groups and teams. Initially, this article introduces the reader to the main differences between groups and teams in the project management field itself, explaining how the members interact and coordinate the tasks assigned, and generally observing how the project manager is involved in the two different cases.

Subsequently, according to Katzenbach and Smith (1993)[2], the focus is switched to the impact that groups, or teams can have on projects in terms of performance and effectiveness. In this paragraph, a deep explanation of the features of different types of teams is provided. In addition, following the team performance curve, the attention is paid on the path that leads working groups to become high-performing teams.

At this point, it results important to explain, according to an adapted model of David Casey (1993)[3], when the organizations ought to choose a group instead of a team for managing a project. The crucial role is played by uncertainty, which is a clear indicator of when a team is needed, or if the “individual bests” of a group are enough to face the intricacies of the project.

Eventually, possible issues within the team and groups are discussed. This is the case, in particular, of "Groupthink" [3], situation that can occur when members recognize themselves as part of a cohesive team which leads to counter-productive results and lowers the level of the performance. This last part is followed by a possible solution with the development of the "Teamthink" mentality.

Introduction: groups vs teams

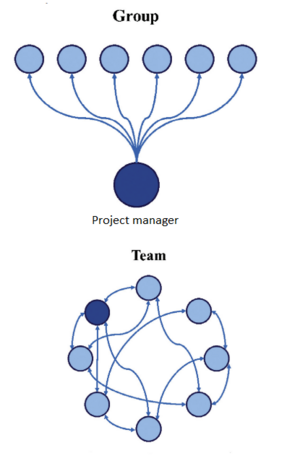

In order to dive into the criteria used within a company to form groups and teams, an introduction about the main differences between the two is first needed. In our everyday life, the words “teams” and “groups” are often used equally just to refer to a number of people combined together due to their common interests, or to their friendship and so on. Regarding the project environment, it is most likely that groups and teams are working on the same project itself, and this is the reason why a strict distinction has to be underlined.

A group is a collection of individuals[4] working individually on their own agenda, without collaborating with the other members, in order to reach a common purpose. In this case, there is no cross-sharing of information, no synergy, and lack in unity of purpose[3]. In groups, the project manager is responsible to take decisions and each member of the group communicates only with the manager, who represents their only reference point. This type of management kills creativity and also decision making process, and individual problem-solving cases are set to be the least possible for group members, while the responsibility of the decisions taken depends just on the project manager[3].

On the other hand, a team is defined as a cohesive smaller group of people working towards the same aim (the team agenda). Team members have authority and autonomy to pursue their own ideas and are committed to the common vision of the team [4]. They work to reach relevant solutions for the project and are highly motivated, involved and responsible for their own work[3]. According to [1] in a more and more uncertain and risky market, the improvement of productivity and job satisfaction through the creation of a team is the best starting point for success. “A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993)[2].”

From group to team: The Team Performance Curve

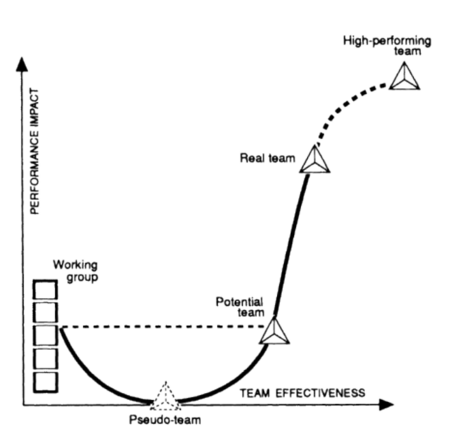

Katzenbach and Smith in 1993 [2] developed the “Team performance curve” which illustrates the steps a generic group have to go through in order to become a high-performing team. Looking at Figure 2, the working group can turn into four different types of teams with the final scope to reach the best performance impact and team effectiveness.

Working group

The curve starts with the working group. It is a group of individuals whose total output is the sum of “Individual bests” [5]. The members’ interaction is focused mainly on sharing information useful for each individual to operate and manage the respective area of responsibility, so there is no jointly effort in reaching the goal predetermined. The group is created for a specific task and, for this reason, frequent changes to the group do not affect the overall performance. The group is considered as a low-risk environment, where the members do not have to take responsibilities beyond their tasks [3].

Pseudo team

According to Katzenbach and Smith, 1993[2]: “In pseudo-teams, the sum of the whole is less than the potential of the individual parts”. The process of turning into a team rather than a working group, requires the members to be ready to face conflicts, but what happens is that some teams are not able to get over this stage, creating what are called “Pseudo-teams”. As stated before, in order to become a team, the members have to commit to common aims and work collectively to achieve them. In “pseudo-teams”, however, members are not willing to take the risk of being a team, avoiding to cooperate towards the same purposes. As a consequence, performance goals are not set and the “pseudo-teams” stand at the bottom of the graph (Figure 2), being the weakest team in terms of performance. The project, or team managers, have to go through this phase focusing on how the members can effectively contribute to the common aim and, as a consequence, to become a stronger team. A potentially dangerous idea related to pseudo teams is for them to pretend to be considered as a “Real team”, while delivering lower-quality results [3].

Potential team

Potential teams are part of each organization. Members strive to improve the overall performance of the team, as usually there should be either more clarity regarding the final objective, or a stricter form of discipline towards a combined working approach[2]. In addition, workers are still on their way to reach a mutual accountability. With a quick glance at the graph in Figure 2, the path from “Potential team” to “Real team” is the steepest as teams in this stage go through different relationships-related difficulties and problems in delivering high-performance tasks. “Potential teams that take the risks to climb the curve inevitably confront obstacles. Some teams overcome them, others get stuck. The worst approach a stuck team can show, however, is to abandon the discipline of the team basics. Performance, not team building, can save potential teams, no matter how stuck”.[2] Moreover, the line between “Working Group” and “Potential Teams” represents the concern of the groups to become teams. Developing a team attitude means fully commitment to the common purpose, willingness to face project-related issues and interpersonal team-members problems, and to embrace the idea of mutual responsibility within the whole team; not all the members are capable to be part of a team, this is why the process requires proper competencies, high-level of expertise, and a rigorous hands-on attitude to work closely with others.

Real team

Real teams include precise features[2]:

- Small number of people: theoretically, also a large number of people can become a team; however, the possibility that a big team of people split into sub-teams is high. The main causes could be the difficulties of collaborating, sharing information and taking jointly accountability. Moreover, issues in finding common spaces and the right time to meet all together can spring up [2].

- Complementary Skills: three main categories of skills are underlined. Technical or functional expertise, problem-solving and decision-making skills, and interpersonal skills. The combination of all the three categories make a team successful and ensure noticeable levels of performance. On the contrary, overemphasizing the skills in the team selection is a common error, as the teams ought to be also a powerful way of learning and development.

- Commitment to the purpose and to the performance aims. Teams are totally committed to reach a common goal. Members work, collaborate, and interact towards high-level performances. Team workers are also willing to face conflicts and to go over relationships’ issues in order to reach the predetermined aim. The purpose is clear, the strategy is set and mutual accountability lead each person to feel motivated and appreciated.

To sum up, Katzenbach and Smith described the “Real Teams” as[2]: “A small number of people who have complementary skills and where each individual exhibits the same level of commitment to a common purpose and a shared and agreed working approach for which they are mutually accountable. Real teams also display characteristics that respond positively to adversity.” “Real Teams” are capable to generate high performance impacts being effective. The curve to "High-Performing Team" is not as steep as the previous stages, but still there are some considerations, mainly related to members interactions, that have to be taken into account.

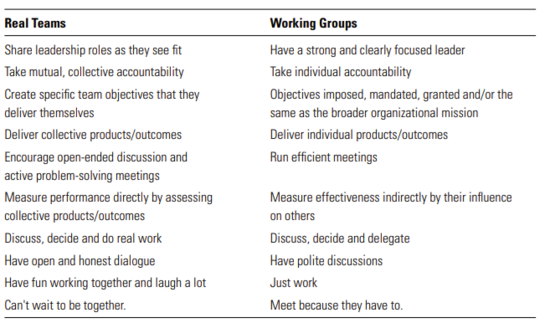

In order to give an example, in Figure 3, the most important differences between "real team" and "working group" are highlighted, according to Burke and Barron [3].

High-performing team

The characteristics presented on the “Real Team” are met. The big difference is related to the fact that the high-performance team members are enthusiastic to help each other, are committed to one another’s personal growth and success. The ambition of reaching the highest levels of performance is even stronger and the complementary skills ensure each individual to be interchangeable and willing to operate in each task[3]. This is the deepest and most powerful example for “Real” and “Potential” Teams aiming to reach the most qualitative performance-based result in a project.

How to choose between group and team: the role of Uncertainty

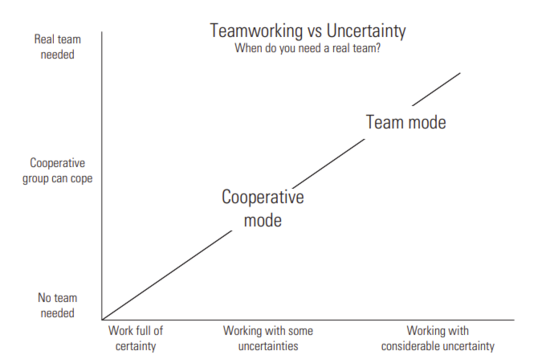

In the previous paragraphs, it is illustrated the path a group should undertake to become a team and, in the best scenario, an "high-performing team", based on Katzenbach and Smith theory. Nonetheless, in some circumstances, companies have the necessity to create working groups instead of teams, or vice versa. According to David Casey [4], the level of uncertainty of a project, or task, is a criterion to decide whether a group, or a team is the most suitable for that project, or task itself. Before going into details, it is interesting to define what can be considered, and what can cause uncertainty in a project. To start with, in uncertainty, the outcome of an imminent event is totally unknown, and the company, or team, lacks in information regarding the background of that event [6]. Some of the most common sources of uncertainty in project management are [4]:

- Changes in customer requirements: uncertainty related to the customers’ preferences in terms of delivery time, quantity purchased and willingness to pay a determined amount for a product/service.

- Changes in technology: during the development phase of a project, it might happen that technologies are updated and not available to be used in the final product anymore. Uncertainty is given by the fact that there are new rules regarding the necessity of a new up-to-date equipment, or process, or the willingness to upgrade the existing ones.

- Lack of resources: difficulty in finding the right resources in terms of components, services and products derived from suppliers, but also hurdles in recruiting people into the team with a proper level of expertise and competences. In addition, it is credible to think at lack of resources as the lack of current assets needed to face equipment and employees costs.

- External factors: if the country where your business is placed and sustained is having economical difficulties, people can be less willing to spend money with a tendency to save up as much as possible for future needs. This behaviour leads clients to change directions towards more convenient possibilities, even though the quality of the product/service offered may be second-rated.

- Timing and coordination issues: these type of problems are related to uncertainty in the duration of the project, or of each task, or even in the sequence in which the different tasks ought to be implemented.

Figure 4 [3] represents the correlation between uncertainty and the necessity of a team, or a group in a project. The overall tendency is described by the urgency to create a team when the uncertainty, embedded in the project, increases. According to [7]: “Project managers can’t predict the future, but accurately gauging the degree of uncertainty inherent in their projects can help them quickly adapt to it”.

The best scenario would occur in absence of uncertainty. This case can be defined as an ideal one, or related to small daily tasks, as uncertainty is an inevitable part of most projects and even the best managers struggle in dealing with it [7]. At the beginning of the curve, in a work full of certainty, the final result of each project is the sum of the “individual bests”, so groups are preferred and there is not an incoming necessity to create a team. Following the trend, working with some uncertainties requires more knowledge and competences. The project needs to be split into different tasks and this is why different groups deal with it in a cooperative mode. The project is divided into tasks assigned to each group, and for each group even smaller tasks are managed by the different individuals. The sum of the “individual bests” of each group is the final result of the project. If little uncertainty is estimated to be part of the project, the project manager is mainly a coordinator and scheduler, planning task using task-breakdown structures and critical-path methods [7]. Lastly, if the uncertainty is a considerable part of the project, solid experience and the right expertise of the team (and project manager) is crucial [8]. Forming and developing a team is seen as a necessity, complementary skills and a strong commitment to reach the common purpose are unavoidable. The higher the level of uncertainty embedded in a project, the more the team might have to redefine the tasks, or even the entire structure of the project, in midcourse [7]. An efficient strategy would be represented by starting the project with the same assumptions on how changes will be managed among all the team members. Teams have to go beyond management crisis and when new information springs up, they must be willing to learn and explore new possible and feasible solutions [7].

Limitation in teams: the Groupthink theory

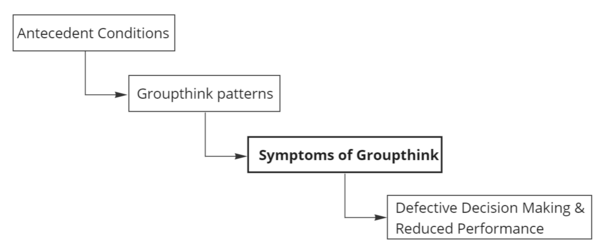

Within teams, however, different issues can arise. One totally correlated to the cohesiveness and the consequent outcome (and performance) of the project is the “Groupthink” theory (Figure 5), first explained by Irving L. Janis in 1972 [10] as: “Quickly and easy way to refer to a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action”. In other words, Groupthink is the behaviour adopted by members of a moderately or high-cohesive team, to evaluate the cohesion of the team itself (showed as a collective pattern of thinking) more important than, instead, pragmatically analyze objective reality[11], in this case regarding the project management context [3]. Overall, the idea in which Janis’ framework is built around occurs when team demonstrates to be cohesive. Thus, the already existing antecedent conditions rise exponentially the probability that the team will show symptoms representative of Groupthink. In addition, the symptoms will lead to noticeable flaws in the team’s decision-making processes, and, consequently, to an impact in the final teams’ performance [9].

Antecedent conditions, Symptoms, and decision-making influence of Groupthink

The antecedent conditions are explained as the causes that “produce, elicit or facilitate the occurrence of the syndrome” [10]. The primary antecedent condition is the cohesiveness of the team. It is manifested through “amiability and spirit de corps among the members” [10] resulting in the willingness of the members to continue being part of the team, in which they feel respected, and esteemed. Even though team cohesiveness is a must for developing a Groupthink mentality within the team, it is not a sufficient condition. Indeed, the secondary antecedent conditions are either related to organizational procedures, as for example leader’s decision preferences, insulation of the group, lack of norms for standardization of the processes, and members’ background; or to the decision-making environment, as for instance stress derived from external threats, difficulties in delivering tasks, and team’s behavior adopted after precise circumstances (recent failures/achievements) [9][10]. The antecedent conditions above mentioned are considered by Janis (1972) [10] as the causes that foster the birth of the symptoms of Groupthink. The 8 symptoms are summarized below [10] [12]:

- Invulnerability: team illusion to be invulnerable which drives to be overoptimistic and unconcerned, in some extent, to risks [10].

- Morality: team’s morality is considered unquestionable leaving unsaid personal ideas and thoughts during meetings.

- Rationale: warnings and negative feedback that may lead the team to reconsider some decisions are discounted.

- Stereotypes: team members are oblivious to the capabilities of the competitors.

- Self-censorship: team members avoid to express their personal opinion in order to remain “loyal” to the team’s consensus.

- Unanimity: a team member who remains silent during discussions agrees with the others’ opinion.

- Pressure: divergent opinions are doubted and not welcomed.

- Mindguards: members work as a filter of ideas to avoid that new information can undermine the effectiveness of previous decisions.

When the symptoms of Groupthink occur, it might be that the decision-making processes are compromised and, therefore, the quality of the final performance of the project decreases. According to Janis (1972) [10], the resulting decision-making processes affected by the Groupthink mentality are:

- Incomplete assessment of alternatives and objectives.

- Failure to: evaluate potential risk of the choices analyzed, reconsider initially rejected options, and work out contingency plans.

- Biased processes of gathering information correlated to poor information research.

Possible solution: the Teamthink theory

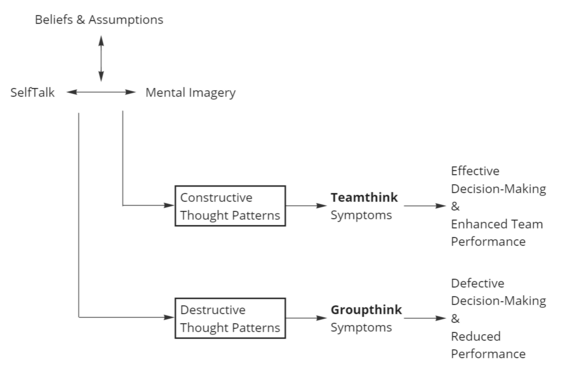

As seen above, cohesiveness can be a very first indicator of the possibility of groupthink to take place within a team. However, collective thinking can also impact positively the outcomes of a project, and this is the case of Teamthink. Teamthink and Groupthink are illustrated in Figure 6. Teamthink theory is based on team beliefs and assumptions, which both depend on team self-talk and team-imagery[9]. Self-talk essentially refers to what each person of the team tells one elf and it's described as a self-influence. A constructive self-talk improves individual performance and, as a result, cause an impact on team performance [9]. Mental imagery, instead, is described in management as a process in which “we can imagine the results of our behaviour before we can actually perform” [9], so the outcome of a task in a project can be actually imagined even before being completed, leading the team to an improvement of the overall strategy. Due to its beliefs and assumptions, the team can create thought patterns, which are defined as the standardization of the team’s ways of thinking, as for instance if the members are oriented towards optimistic or pessimistic decisions. At this point, if the thought patterns are constructive, the team ends up showing the Teamthink symptoms [9]:

- Recognition of member’s uniqueness which leads to open expression of one's ideas.

- Encouragement of divergent views

- Awareness of external and internal threats and consequent assessment of shared doubts.

Teamthink, as opposed to Groupthink, enhances the team performance through the increase of effectiveness in decision-making [9], guiding the team members to develop a shared positive attitude.

Annotated Bibliography

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Groups vs. Teams: Which One Are You Leading?, Cori Armstead, MSN, RN, CEN, Dustin Bierman, DNP, RN, Pam Bradshaw, DNP, MBA, RN, NEA-BC, Thalia Martin, DNP, RN, CPHQ, and Karen Wright, DNP, RN-BC, June 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization, Katzenbach, Jon R.; Smith, Douglas K., Harvard Business School Press, 1993

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Project Management Leadership: building creative teams, Rory Burke, Steve Barron, 2nd edition, 2014

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Principles of Management, University of Minnesota, 2015

- ↑ Katzenbach and Smith: Praxis Framework, https://www.praxisframework.org/en/library/katzenbach-and-smith

- ↑ Risk vs Uncertainty in project Management, https://pmstudycircle.com/risk-vs-uncertainty/, University of Minnesota, 2015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Managing Project Uncertainty: From Variation to Chaos, De Meyer, Loch, Pich, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2002

- ↑ Uncertainty and its effects on project teams, https://pm-alliance.com/project-teams-uncertainty/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 From Groupthink to Teamthink: Toward the Creation of Constructive Thought Patterns in Self-Managing Work Teams, Christopher P. Neck, Charles C. MAnz, 1994

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Groupthink: a revied and enlarged edition of Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes, Irving L. Janis, Yale University, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 1972

- ↑ Groupthink: A Study in Self Delusion, Christopher Booker, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020

- ↑ Management communication: the threat of groupthink, Jack Eaton, University of Wales, 2001