Extrinsic Motivation in the Workplace

(→Application in the Workplace) |

|||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

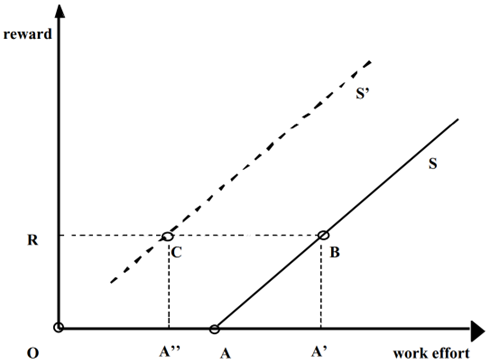

When looking at the different forms of extrinsic motivation, SDT specifies four different forms that are shown on the self-determination continuum in Figure 1. These include external regulation, introjection, identification, and integration. To the far left in the black box, amotivation is located. Here, the individual is not motivated and few to none of their basic needs are met. To the far right in the green box is the opposite situation, an individual entirely driven by intrinsic motivation. When moving from left to right on the continuum, the form of motivation becomes gradually more intrinsic <ref name=''7''> '' Levesque, C., Copeland, K. J., Pattie, M. D., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. In Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance. Elsevier.'' </ref>. | When looking at the different forms of extrinsic motivation, SDT specifies four different forms that are shown on the self-determination continuum in Figure 1. These include external regulation, introjection, identification, and integration. To the far left in the black box, amotivation is located. Here, the individual is not motivated and few to none of their basic needs are met. To the far right in the green box is the opposite situation, an individual entirely driven by intrinsic motivation. When moving from left to right on the continuum, the form of motivation becomes gradually more intrinsic <ref name=''7''> '' Levesque, C., Copeland, K. J., Pattie, M. D., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. In Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance. Elsevier.'' </ref>. | ||

| − | [[File:Continuum2.JPG|frame|Figure 1: Continuum of self-determination, own figure based on reference | + | [[File:Continuum2.JPG|frame|Figure 1: Continuum of self-determination, own figure based on reference <ref name=test/>.]] |

==== External regulation ==== | ==== External regulation ==== | ||

Revision as of 21:56, 9 May 2023

Author: Philip Alexander Østergaard Brandt - s164495, Spring 2023

Abstract

This article explores the concept of extrinsic motivation that is used by companies and organizations to increase the performance and productivity of the employees through external punishments or rewards. To better understand extrinsic motivation, the article debates the self-determination theory’s three psychological needs for intrinsic motivation: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The article also covers the categorization of the four types of extrinsic motivation, based on the degree of self-determination. Furthermore, it is discussed what an organization should consider before applying extrinsic motivation, and what they can do to mitigate the risks. The article concludes that companies should be careful when using extrinsic motivation as this might impact the intrinsic motivation of the employees in the future. Furthermore, extrinsic motivation is only a short-term solution and should not be the only motivational factor, thus making it important that the company also fulfils the employee’s psychological needs, to maintain their intrinsic motivation.

Contents |

Introduction

In the realm of project, program and portfolio management, the motivation of the employees plays a significant role. Motivation refers to the inner drive propelling individuals toward specific goals [1]. There are two distinct types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. If an individual is intrinsically motivated, they obtain personal satisfaction from performing tasks they enjoy; while if someone is extrinsically motivated, they are motivated by outside forces like rewards or punishment. In project, program and portfolio management, organizing the workforce through external motivators can be an instrumental tool in generating positive results and reaching milestones on time. By linking individual incentives with collective goals, companies can create an environment where workers strive to perform their best, leading to greater success rates and higher profitability. Extrinsic motivation is an important factor in project, program and portfolio management; however, it is not specifically mentioned in the standards. The standards aim to provide guidance that is applicable in a wide range of scenarios but also recognize that project, program and portfolio management is highly context-dependent. Thus, it is difficult to provide standardized guidance for the application of extrinsic motivation as it is very subjective and dependent on individual factors, which will also be discussed throughout this article.

Extrinsic Motivation

To understand extrinsic motivation, one must first understand where the term becomes relevant. In the 1930s, the American psychologist and behaviorist B. F. Skinner, began studying reinforcement theory [2]. The reinforcement theory builds upon the assumption that the behavior of an individual can be shaped through the consequences of its actions. Behaviors or actions that lead to positive consequences, such as rewards, are more likely to occur again, whereas actions leading to negative consequences, such as punishment, are less likely to be repeated. This phenomenon is also referred to as the law of effect and aims to understand and predict the impact of the consequences on behvaior. The consequences that reinforcement theory aims to predict the outcome of, can be referred to as extrinsic motivation. The external factors reward or punishment, can be used in different ways. The rewards can be classified into two categories: intangible rewards and tangible rewards. Intangible rewards refer to emotions and psychology and are non-physical. Examples of this would be recognition, sense of accomplishment or praise. Tangible rewards refer to items or objects and are physical. Examples of this would be salary, bonusses or gifts. To decrease the likelihood of a certain action repeating itself, one can apply the other category of extrinsic motivation, punishment. As with rewards, there are also two main categories for punishment: positive punishment and negative punishment. To apply positive punishment, one must add something unpleasant to decrease the undesired behavior. This could be assigning an employee with extra work or simply assigning them an unpleasant task. Moving on to negative punishment, it involves removing something desirable, also with the goal of decreasing an undesired behavior. This could be things such as taking away an employee’s bonus or privileges [3].

Self-Determination Theory

When applying extrinsic motivation, one must consider how it affects the individual's intrinsic motivation. To understand the impact of extrinsic motivation on intrinsic motivation, the self-determination theory (SDT) was developed by Edward L. Deci and Richard Ryan. According to SDT [4] , an individual has three different psychological needs to be intrinsically motivated: autonomy, competence, and relatedness [5]. If one of these basic needs are not met, it might result in frustration, loss of interest or being disengaged in their work, thus reducing their intrinsic motivation [6] [7]. A lack of autonomy in one's work can be caused by having little to no control over tasks, decisions, or schedules. This could be a consequence of being micromanaged, thus taking away the individual’s room for independent thoughts and actions. Following this, the employee might start feeling like they have no impact, and the work is becoming less meaningful. An example of lack of competence at work could be that an employee is assigned to a task that they cannot solve, which could be due to lack of training or being unfamiliar with the task. This can cause the employee to doubt their abilities and feel like they are underqualified for the task, which can lead to frustration and feeling insecure. An example of lack of relatedness could be if an employee feels disconnected from their co-workers or organization. This can lead to loneliness and a feeling of doing work that is meaningless as they are not part of the “community”. When looking at the different forms of extrinsic motivation, SDT specifies four different forms that are shown on the self-determination continuum in Figure 1. These include external regulation, introjection, identification, and integration. To the far left in the black box, amotivation is located. Here, the individual is not motivated and few to none of their basic needs are met. To the far right in the green box is the opposite situation, an individual entirely driven by intrinsic motivation. When moving from left to right on the continuum, the form of motivation becomes gradually more intrinsic [8].

External regulation

External regulation is located the furthest to the left of the four different forms of extrinsic motivation, in Figure 1. This means that it is the one with the lowest degree of self-determination and is often referred to as extrinsic motivation. The idea behind external regulation is to make the individual either chase a reward or avoid a negative consequence. An example of a reward would be if an employee worked extra hours to receive their bonus, whereas a negative consequence would be working extra hours to avoid getting laid off.

Introjected regulation

Introjected regulation is a type of extrinsic motivation that makes the individual perform certain actions by internalizing external pressure. This could be things such as the desire to avoid feeling guilt, shame, or fear. As with external regulation, introjected regulation is also driven by pressure, but with external regulation the pressure comes from the “outside” as contrary to internal where the pressure comes from the inside. An example of this could be an employee taking on additional tasks as they may feel like they are letting down their colleagues or organization if they do not, which creates a fear inside the employee, thus pressuring them internally.

Identified regulation

Identified regulation occurs when a behavior has been regulated through identification. This means that the behavior of an individual has been regulated through certain actions and now the individual is identifying itself with the given behavior. When this occurs, the individual is still extrinsically motivated because they are trying to reach a goal, but as they start valuing the activities, that must be completed to reach the goal, they start identifying themselves with the behavior, resulting in self-determination. An example of this could be an employee who is working on a project understands how important the project is for the goal of the company. The employee could also see the project as an opportunity for developing competences that could help them advancing in their career.

Integrated regulation

This type of motivation is the furthest to the right on the continuum in Figure 1, thus making it the type of extrinsic motivation with the highest degree of self-determination. With integrated regulation, the individual’s behavior is not only regulated, but the individual has also integrated the behavior and thrives in it. An example of this could be that an employee who is very passionate about sustainability is allocated to a sustainability project. This would align their personal values with the project, thus seeing the project as an opportunity to contribute to a cause that they are passionate about.

Application in the Workplace

In organizations, it is critical to keep the employees motivated [10]. Extrinsic motivation makes it possible for the organizations to determine the actions and also investigate behavior models of the employees. In almost every company, the employees are extrinsically motivated by their salary, which is rewarded for doing their work. However, despite having a satisfying salary, it takes more than that to keep an employee motivated, which companies are aware of. A common extrinsic motivation tool is bonuses, which close to all companies use. This is to ensure that the employee does not show up to work just to be present, but also tries to perform, thus triggering the bonus. These rewards are tangible, but the intangible extrinsic rewards are also taken into use in a lot of organizations. This is done by publicly announcing the employee of the month, giving out promotions and praising employees in public [11].

A company that is known to make use of extrinsic rewards is Google [12]. Google does a great job at keeping their employees motivated through various initiatives. Examples of these are flexible spending accounts, free health and dental benefits, vacation packages, an onsite hair salon and Google even allows its employees to spend 20% of their working hours to pursue special projects and interests. These benefits are just the tip of the iceberg, but also raises the question as to how Google can stay profitable with such initiatives in place. The answer is simple, Google has managed to balance their employees extrinsic and intrinsic motivation by providing extrinsic rewards in deliberate manner. This has not only resulted in the employees performing well, but Google employees also usually surpass management expectations, which means that the extrinsic motivation is a profitable initiative from the management.

Motivation Crowding Theory

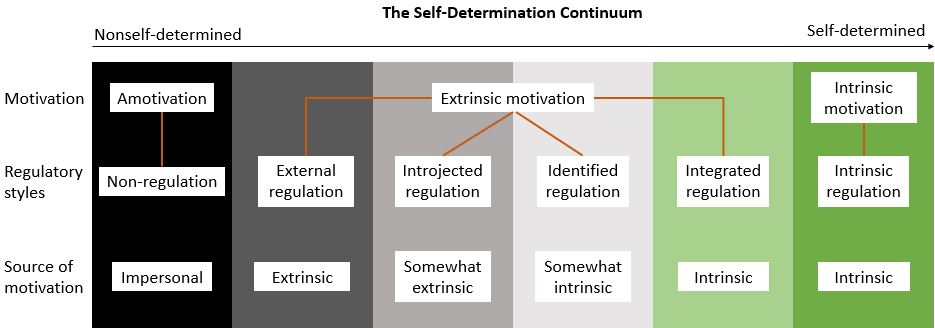

When an organization is looking into the motivation of their employees and how they should use extrinsic motivation, motivation crowding theory must be considered. Motivation crowding theory is a concept that refers to the idea that extrinsic motivation might impact one’s intrinsic motivation, negatively. According to the theory that was first introduced in 1970 by Richard Titmuss, extrinsic motivation might “crowd out” the intrinsic motivation. In Figure 2 there are shown two graphs, S and S’. Looking at the graph S, when the extrinsic reward is increased from O to R, the work effort also increases from A to A'. However, as soon as motivation crowding becomes present, the individual’s work effort will switch to the graph S’. In this case, the raise of extrinsic rewards from O to R will now move the individual's work effort to C, instead of B. In this scenario, the increase in rewards causes the work effort to go from A to A'' as the intrinsic motivation has now been crowded out and the individual is only motivated by extrinsic rewards. Once this happens, their behavior will now follow the S' graph and the work effort can be increased by increasing the external reward [13]. Motivation crowding theory is relevant in all organizations and should be understood by all project, program and portfolio managers before giving out rewards. If done incorrectly, the extrinsic rewards might end up decreasing the intrinsic motivation of the employees, also known as the overjustification effect [14].

Overjustification Effect

The overjustification effect arises when an individual is externally rewarded for something that they previously found interesting and exciting without receiving any rewards, for instance taking on extra tasks at work or being in charge of arranging the Friday bars. Once this happens, it will become more difficult for the person to perform the given activity without being extrinsically motivated. This makes it even more important that organizations are careful when making use of extrinsic rewards as a motivational tool. Over an extended period of time, research shows that an employee that receives extrinsic rewards for completing a task they find enjoyable, leads to decreased intrinsic motivation for the task in the future [15]. In order to mitigate this risk, there are several things an organization can do, which will now be discussed.

Timing of Reward

First, the organization must consider when the timing is right for the rewards. Many organizations choose to pay out bonusses for successful projects after they are completed. This might seem logic, however, offering an employee a reward after completing a task, is more likely to decrease their intrinsic motivation than if they are rewarded during the task, which could for example be as a progress payment. This is due to the fact that the employee might view the task as being completed for the reward rather than the enjoyment of the task. If the reward is given during the task the employee is more likely to interpret it as an encouragement to keep up the good work instead of the reward being the primary goal for the task.

Purpose of Reward

Secondly, an organization must pay attention to the purpose of the rewards. The rewards should be given to increase the overall success of the company. However, one should not tie the rewards to a very narrowly defined target or goal, which could be giving the employees an individual sales target. Instead, the companies should connect the rewards with broader goals, thus incentivizing teamwork rather than the employees only focusing on their own sales. An example of this being done wrong occurred in 2016 when the Wells Fargo cross-selling scandal took place [16]. The company tried to utilize extrinsic motivation by implementing a performance-based salary, which rewarded the employees for opening new credit cards and checking accounts, however, the sales quota was set so high that the employees started opening accounts for customers without their consent. Furthermore, the initiative resulted in individually rewarded performances, incentivizing the employees to think of themselves rather than their colleagues and the company.

Type of Reward

One more important thing to consider when making use of extrinsic motivation, is that the reward should be aligned with the employee’s interests, which makes the reward seem more supportive rather than controlling, thus avoiding a reduction in intrinsic motivation. A mistake made by countless companies is to award the employees under the assumption that they all desire the same thing, money. Some people will be motivated by having more flexible hours of work or being granted extra vacation days while others will be motivated by step-up opportunities. If an organization takes time to align the type of rewards with the employees through personal meetings, it will make them feel appreciated and not like a small fish in a big pond.

Risk of Creating a Bribing Mentality

When a company makes use of extrinsic motivation by giving out rewards to employees, there is also the risk of creating a bribing mentality. The employee will be happy with the reward they receive, whenever they complete the given task. However, after some time there is a risk that the employee will start to expect a reward every time, they complete a task, known as the bribing mentality. When this expectation is present, the employee might stop striving to deliver a great piece of work and instead only deliver the bare minimum required for them to obtain the reward, as extrinsic motivators does not create passion. To avoid creating a bribing mentality a company can assure that the rewards are given out in a consistent way and are aligned with the values of the employees.

Limitations

When applying extrinsic motivation in the workplace, organizations are in great danger of reducing the individual’s intrinsic motivation in the process, as discussed above. Extrinsic motivation should always be applied as a short-term strategy to motivate the employees into achieving certain goals as it may not lead to sustained performance and engagement in the long term. This is because extrinsic rewards can make the individual focus on the rewards rather than the task itself. Furthermore, employees might become more hesitant to take on tasks that do not offer a clear extrinsic reward, making the individuals mostly focused on tasks that offer the most immediate benefits. Extrinsic motivation is overall a tool that can lead to great results if applied properly. It is, however, not possible to replace poor management or bad workplace conditions with extrinsic rewards, but it can be used as a supplement in an overall healthy organizational culture.

When looking into which organizations should be applying extrinsic rewards, it might not be suitable for all lines of business. Companies in more creative lines of work might be hindered by the use of extrinsic rewards. This is because the nature of their work requires a higher level of autonomy, and therefore it is important not to stifle their creativity and intrinsic motivation. Lastly, organizations such as non-profits or socially responsible businesses should also be extra cautious when considering the use of extrinsic motivation, as this kind of work is already inherently rewarding.

Annotated Bibliography

The annotated bibliography included in this article outlines the key references that have been utilized for this article. These references can be studied to obtain more in-depth knowledge about how to apply extrinsic motivation in the workplace.

- Studer, B., & Knecht, S. (2016). Chapter 2 - A benefit–cost framework of motivation for a specific activity. In B. Studer & S. Knecht (Eds.), Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 229). Elsevier.

- - This article discusses a framework that aims to understand how an individual can be motivated to perform a task or activity. The framework assumes that motivation is determined by the expected benefits and expected costs. The benefits are divided into two categories: intrinsic benefits, such as the positive feelings one would gain through the activity, and extrinsic benefits such as the rewards the individual would receive. Similarly, the costs of the framework can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic costs. By taking these factors into account, the framework aims to increase the motivation for a specific exercise.

- Kwok, A. O. J., Watabe, M., & Ahmed, P. K. (2021). Excessive extrinsic rewards in workplace relationships. In Augmenting Employee Trust and Cooperation (Chapter 2). Springer.

- - In the debate of extrinsic motivation, this article is highly relevant. It discusses the effect of excessive extrinsic rewards in the workplace and how one can predict the reactions of the employees. Here, excessive extrinsic rewards refer to monetary rewards that exceed the expectations of the employee. This piece is especially useful for managers who are interested in learning about the relationship between extrinsic rewards and the motivation of their employees. The article also provides suggestions about how an organization can structure their reward systems to promote employee trust and cooperation.

- Putra, E. D., Sukesi, T. R., & Indriani, W. (2017). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on work engagement in the hospitality industry: Test of motivation crowding theory. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(2), 228-241.

- - This paper describes a study that was conducted in the hospitality industry to empirically test the motivation crowding theory and determine the impact of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on the work engagement of the employees. The study discusses some unique findings, differing from most research conducted within the field. One of the findings was that there was no indication that extrinsic motivation would diminish the intrinsic motivation of an employee. The finding of this study confirms just how complex the topic of extrinsic motivation is, thus making this article relevant to people who want to gain an even deeper understanding of the subject, in addition to the general knowledge.

- Frey, B. S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(5), 589-611.

- - This study examines the motivation crowding effect and demonstrates the fact that it is also of empirical relevance. The article states that there is empirical evidence that supports the existence of crowding-in and crowding-out, thus confirming that it is not just a theory. Evidence is presented in the form of laboratory studies conducted by both psychologists and economists and furthermore, field research by econometric studies. The evidence in the article is gathered from different areas of the economy, different societies and countries. Thus, making it relevant to anyone who wants to dig deeper into the empirical relevance of the motivation crowding effect..

- Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Grouios, G., & Sideridis, G. (2008). The assessment of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and amotivation: Validity and reliability of the Greek version of the Academic Motivation Scale. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 15(1), 39-55.

- - This article explains self-determination theory and proposes a continuum with three types of motivation: intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation characterised by seven dimensions. It describes two studies that focused on the Greek version of the academic motivation scale (AMS), thus allowing the reader to gain a deeper understanding of self-determination theory. The results of the study indicate that the Greek version of the AMS has satisfactory levels of consistency which allows it to be used for assessing intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation for Greek high school students. The study is relevant for people interested in the measurement of motivation in an academic context.

References

- ↑ Motivation. Oxford Reference. Retrieved 6 May. 2023, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100212318.

- ↑ Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of Organisms. New York: Appleton-Century.

- ↑ McConnell, JV. (1990). Negative reinforcement and positive punishment. Teaching of Psychology 17(4): 247–49. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1704_10.

- ↑ Wang, C. K. J., Liu, W. C., Kee, Y. H., & Chian, L. K. (2019). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: Understanding students' motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon, 5(7)

- ↑ Law, L., Wilson, D., Lawman, H. G., & Delamater, A. M. (2020). Self-Determination Theory. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine, 1980–1982. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_1620

- ↑ Studer, B., & Knecht, S. (2016). A benefit-cost framework of motivation for a specific activity. Progress in Brain Research, 229

- ↑ Amabile, T. M. (1993). Motivational synergy: Toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review

- ↑ Levesque, C., Copeland, K. J., Pattie, M. D., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. In Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance. Elsevier.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedtest - ↑ Kwok, A. O. J., Watabe, M., & Ahmed, P. K. (2021). Excessive extrinsic rewards in workplace relationships. In Augmenting Employee Trust and Cooperation. Springer Singapore.

- ↑ Gerhart, B., & Fang, M. Y. (2015). Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, performance, and creativity in the workplace: Revisiting long-held beliefs. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 489-521.

- ↑ Luenendonk, M. (2019, September 16). The Google Way of Motivating Employees. Cleverism. https://www.cleverism.com/google-way-motivating-employees/

- ↑ Frey, Bruno S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation Crowding Theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, vol. 15, no. 5, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 589–611

- ↑ Weibel, A., Wiemann, M., & Osterloh, M. (2014). A behavioral economics perspective on the overjustification effect: Crowding-in and crowding-out of intrinsic motivation. The oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory, 72-84.

- ↑ Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 627–668

- ↑ Kelly, J. (2020), Wells Fargo Forced To Pay $3 Billion For The Bank’s Fake Account Scandal. Retrieved March 17, 2023 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2020/02/24/wells-fargo-forced-to-pay-3-billion-for-the-banks-fake-account-scandal/?sh=179aa46442d2