Creating a Learning Organization

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

[[File:Untitled-1.png]] | [[File:Untitled-1.png]] | ||

| − | '''Single-Loop Learning''' | + | : '''Single-Loop Learning'''. Engaging in Single loop learning means reflecting on what is happening now or in the past, and focus attention on detecting errors. Corrective routines are then developed from this feedback, to modify future actions and behaviour. This includes both goals, values, and operating frameworks. Single loop learning can be very useful and is a good tool in continuous improvement, but will never create path breaking behavior. Single-loop learning is specially useful in project and program management, but can also to some extent be useful in portfolio management. |

| − | + | ||

| − | '''Double-Loop Learning''' | + | : '''Double-Loop Learning'''. Re-evaluating the deeper variables that make us behave the way we do is called double loop learning, and happens when leaders are able to think outside the box. It challenges the accepted ways of thinking and behaving, and thereby provide the possibility of developing new understandings of situations and crucial path breaking behavior. Double-loop learning only occurs when leaders are able to deeply reflect on outcomes. This is done by identifying the assumptions that underpine decisions and actions that lead to the achivements, and also identifying those assumptions that defines the definition of satisfactory outcomes. These assumtions should be reviewed and challenged, and where appropriate, modified. Double-loop learning is especially useful in portfolio management, where large, strategic decisions are to be made, and a complete re-evaluation of the organization is sometimes necessary. |

| − | + | ||

== Barriers to Learning == | == Barriers to Learning == | ||

Revision as of 14:32, 23 September 2016

A learning organization manages evaluation of projects to capture and interpret information that can benefit future projects. Organizational learning includes both individual and collective learning, which are both important determinants of organizational effectiveness. The ability to learn is a key enabler to organizational success and competitive advantage [1]. In the absence of learning will companies simply keep repeating old practices [2].

But managing the learning is difficult and time consuming, which is why many organizations often fails to do it or completely neglects it. Project managers needs to be able to effectively manage scope, time and budgets in projects, but also human behavior. All of these factors should be included when conducting the learning. It is also important to include all stakeholders and all organizational levels.

The definition of a learning organization has evolved over the years. Organizational theorists have many different suggestions, most view it as a process that unfolds over time, and link it with knowledge acquisition and improved performance [3]. Some believe that changes in behavior is required, others state that it is enough to think in new ways. One definition is: "A learning organization is an organization skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behavior to reflect new knowledge and insights" [4].

Organizations that fit to this definition are capable of translating new knowledge into ways of behaving. They are responsible for their success.

Organizations can apply methods, theories, and tools to better their skills in learning. This article describes the importance of learning in an organization, and how information is created, captured and interpreted, and used in future projects. It also outlines the requirements for creating a learning organization. Lastly it investigates the barriers to learning and how to overcome these.

Importance of Learning

Important information and answers to many questions emerge from experiences. So learning organizations create an environment where employees continuasly seek new knowledge to share with co-workers. They manage to work together and make sure that teams or individual employees have access to exactly the information that is relevant for them in the specific task [5].

Benefits of Learning

There are several benefits to having a learning organization. These include:

- With a high level of maintained knowledge, answers to most questions are available

- Increased knowledge and skills

- Improved work methods and routines

- High levels of innovation in the organization

- Competitiveness in the industry and market

- Fast response to change

- Improved quality of outputs

Principles for Creating a Learning Organization

Peter Senge advanced the theory of Learning Organizations in 1990, when he published his book The Fifth Dicipline, whee he outlines five characteristics for a learning organization that he calls the "learning diciplines":

- 1 Develop personal mastery. How much we know about our selves and is aware of the impact that out behavior has on others is called self-awareness [6]. Developing personal mastery focuses on learning to expand our self-awareness and personal capacity to create desired results. Individual learning is acquired through training and encouragement of continuous self-improvement. But learning cannot be forced on an individual, and it is crucial that employees are willing to learn [7]. Therefore organizations needs to make learning part of the culture, while creating an organizational environment in which organizational members are encouraged to develop skills and disciplines that can help in reaching their goals and purposes.

- 2 Build complex, challenging mental models. The assumptions or "internal pictures of the world" held by individuals and organizations are called mental models[8]. These are part of shaping the way people think and act. To be a learning organization, these mental models need to be reflected upon and continually challenged. Organizational members have to clarify their mental models for each other, while challenging each others' assumptions in order to build a shared understanding [9].

- 3 Promote team learning. When teams start thinking together by sharing individual experiences, insights, knowledge and skills it is called team learning [10]. When teams to team learning they are able to develop greater intelligence and ability than the sum of individual members', which in the end will make an organization more competitive and faster responsive to a changing environment. Team learning is done through openness when team members engage in dialogue and discussions, and through shared meaning, understudying and visions. Excellent management structures that allow development, reflection and challenging of knowledge is required [11].

- 4 Build shared vision. Creating a sense of commitment and common identity in a group to work towards common goals means having a shared vision. Teams need to take time early in the process to build common understandings and commitments, and create shared visions in order to work effectively [12].

- 5 Encourage systems thinking. Systems thinking is a conceptual framework that describes the language and interrelationships that shape the behavior of systems. It helps teams to unravel the often hidden subtleties, influences, leverage points, and intended or unintended consequences plans and programs. It leads to deeper, more complete awareness of the interconnections behind any system [13]. Mapping and analyzing situations, events and problems, can help organizations to detect causes of problems, and plan courses of action to better solutions [14].

Integrating Learning in an Organization

When an organization fails to manage learning, valuable knowledge is thrown away. Learning can and should be implemented in all parts of a process, and on every level of an organization. Integrating learning in a organization requires time and commitment. Peter Senge says "First, you must realize that the very idea of a "learning organization" is a vision".

Michael J. Marquardt argue that before individuals and organizations can adequately learn, they must incorporate five subsystems (figure xx): (1) Learning, (2) Organization, (3) People, (4) Knowledge, and (5) Technology. All five subsystems are dynamically interrelated, and if any is weak or absent, it will have significant effect on the overall learning. Therefore, focus on all five subsystems is necessary to move from non-learning to learning [15].

Knowledge

Management of knowledge is the heart of building a learning organization. There are six knowledge elements of organizational learning [16]:

| Acquisition | Collection of existing data and information from within and outside the organization. |

| Creation | New knowledge is generated through different processes, or through the ability to see new connections and combine previously known elements. |

| Storage | Coding and preservation of knowledge for easy access by any staff member, at any time, and from any place. |

| Analysis and Data mining | Using techniques for analyzing, reconstructing, validating, and inventorying data. Mining enables organizations to find meaning in data. |

| Transfer and dissemination | Mechanical, electronic, and interpersonal movement of information and knowledge throughout the organization. |

| Application and Validation | The use and assessment of knowledge by members of the organization. This is accomplished through continuous recycling and creative utilization of the organization’s rich knowledge and experience. |

The six elements are interactive and interdependent. Organizations that are successful in learning manage to systematically go through each of the six elements.

Levels of Learning

Managers need to realize that an organization consist of many individuals who have different ways of working, different ways of reflecting and communicating and different levels of resistance. Managers need therefore to understand both individual and collective learning, particularly in terms of the extend to which individuals are viewed as autonomous and distinct from social and cultural groups in work activities [17].

Learning exist on three levels:

- Individual learning: the individual human process of consuming and storing new concepts, skills and behaviors. The challenge is to draw out this learning and translate it to capabilities that can be useful for the organization [18].

- Individuals often hold much more information than they share, because it can be very challenging to communicate. The kind of knowledge that is hard to transfer to another person is referred to as Tacit Knowledge or "know-how", and is highly experience based and context-dependent. Though being hard to communicate, tacit knowledge is considered being the most valuable knowledge, and the most likely to lead to breakthroughs in an organization. It is found in the minds of human stakeholders, and include cultural beliefs, values, attitudes and mental models, as well as skills, capabilities and expertise. Focus on the form of knowledge will have impact on the organization's ability in innovation and competitiveness [19]. The challenge is to communicate and translate this information into something useful for others.

- Knowledge that is easy to communicate and standardize is referred to as Explicit Knowledge or "know-what". This type of knowledge is easy to identify, store and retrieve. The challenge here is to ensure that people has access to exactly the information that is relevant to them, and it should therefore continuously be reviewed, and updated or discarded [20].

- Group or team learning: the increase in knowledge, skills, and competencies accomplished by and within groups [21].

- Organizational learning: the enhanced intellectual and productive capability gained through commitment to and opportunities for continuous improvement across the organization [22].

- Learning from each other can sometimes bring the most powerful insights and help in gaining new perspectives. Knowledge must be spread efficiently throughout the organization. Ideas carry maximum impact when they are shared, rather than kept in the team. A variety of mechanisms spur this process. These include written, oral, and visual reports, as well as site visits and tours, which are the far most popular forms, which summarize findings, provide checklists, and describe important processes and events. Other mechanisms include personnel rotation programs, education and training programs, and standardization programs [23].

- Knowledge that is locked to an organization's processes, culture, routines, experiences, artifacts, or structures is called Embedded Knowledge. Knowledge is embedded either formally such as through management initiatives to formalize a certain routines, or informally as the organization uses and applies tacit and explicit knowledge. Embedded knowledge can therefore exist in both tacit and explicit forms, and exist in manuals, rules, processes, and organizational ethics and culture. Embedded knowledge is analyzable in the relationships between, for example, technologies, roles, formal procedures, and emergent routines, and is capable of supporting complex patterns of interaction when there are no written rules [24]. The challenge in this type of knowledge is that culture and routines can be very hard to understand, communicate and change, but effectively managing embedded knowledge can give an organization competitive advantage.

Types of Learning

When talking about learning, we can distinct between three different types. Although each is distinctive, there is often overlap.

- Adaptive learning occurs when reflection over past experiences found the base to modify future actions.

- Anticipatory learning occurs when you envision various different futures, identify the best future opportunity, and determine the best ways to achieve it.

- Action learning occurs when we question and reflect on the reality, and apply this to develop an individual, group or the whole organization.

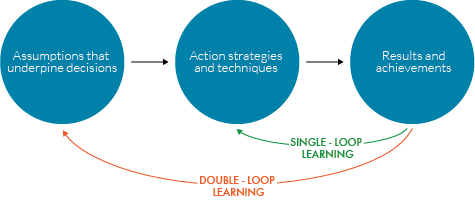

Singe-loop and Double-loop Learning

Argyris and Schön (1978) distinguish between two types of learning; Single-Loop Learning and Double-Loop Learning [25]:

- Single-Loop Learning. Engaging in Single loop learning means reflecting on what is happening now or in the past, and focus attention on detecting errors. Corrective routines are then developed from this feedback, to modify future actions and behaviour. This includes both goals, values, and operating frameworks. Single loop learning can be very useful and is a good tool in continuous improvement, but will never create path breaking behavior. Single-loop learning is specially useful in project and program management, but can also to some extent be useful in portfolio management.

- Double-Loop Learning. Re-evaluating the deeper variables that make us behave the way we do is called double loop learning, and happens when leaders are able to think outside the box. It challenges the accepted ways of thinking and behaving, and thereby provide the possibility of developing new understandings of situations and crucial path breaking behavior. Double-loop learning only occurs when leaders are able to deeply reflect on outcomes. This is done by identifying the assumptions that underpine decisions and actions that lead to the achivements, and also identifying those assumptions that defines the definition of satisfactory outcomes. These assumtions should be reviewed and challenged, and where appropriate, modified. Double-loop learning is especially useful in portfolio management, where large, strategic decisions are to be made, and a complete re-evaluation of the organization is sometimes necessary.

Barriers to Learning

Even though there is a lot of potential in disseminating know-how between projects, many companies fails to do so. This is because there are several barriers to learning in an organization. Zedtwitz (2003) divides barriers into four categories [26]:

- 1 Team based barriers include poor internal communication and reluctance to blame. When team members have different backgrounds and work in different locations, it can be difficult to communicate effectively and fully understand each other. There exist both professional and personal relationships within a team. While personal relationships can help build a stronger team, it also creates a barrier for co-workers to go against each other in situations where it is needed [27].

- 2 Physiological barriers include memory bias and inability to reflect. The human brain has limitations. Our memory is biased and we tend to remember the more positive or negative experiences, and forget the indifferent or common experiences, which can often contain just as useful information. It also tends to suppress complex problems, which are actually often the most important problems to understand and reflect on. Additionally, the brain is from nature not capable of reflecting completely on the past, either because it is hard to link outcomes of previous actions or simply because we do not like to reflect over our own failures [28].

- 3 Managerial barriers include time constrains and bureaucratic overhead. In vast majority of all projects, time is a constraint and teams constantly work under a performance pressure. So often there is no time of reflect on the process, team work and outcomes, even though this might be a big help in future projects by eliminating possible questions or time spend on the same problems. Another managerial barrier is that not all stakeholders in a project is asked to reflect or give feedback to the process. It is most often only the top management that runs checkpoints on time, budget and quality of deliveries, and the root of possible problems are not detected on lower levels where they actually occur, which is a huge barrier to organizational learning [29].

- 4 Knowledge utilization barriers include difficulty in generalizing information and tacit knowledge. Sharing knowledge in a systematic way is difficult and you can end up with immense amounts of information which is pointless to navigate in for future projects. People also know more than they are able to express. It is difficult to express feelings and impressions [30].

Overcoming the barriers

First of all, organizations needs to understand and accept that these barriers exist, in order to manage them.

In order to learn, an organization needs a creative climate, which allows employees to objectively and honestly explore issues. To allow a creative climate, the organization needs to meet a number of preconditions, which can only be met if members from all organizational levels are included, expectations of outcome and success criteria are aligned, and if organizational members are prepared to take risks and accept failure as an opportunity for learning and development [31]. The criteria for a creative climate are:

- Trust and openness

- Challenge and involvement

- Support and space for ideas

- Conflict and debate

- Risk taking

- Freedom

Other critical factors include [32]:

- Shared goals or mission statement

- Personal competences

- Team building and cross training

- Dynamic leadership

There are many different models for organizational learning. While having various different points, there are some areas in which they agree. These include that learning is a continuous process, work should be structured so that it allows experimentation and learning from mistakes, structures and systems are needed to capture the right information and making sure that it is useful for the right people, and innovation is needed, which typically requires double-loop learning [33].

There are, however, also areas in which they do now agree. These include the amount of responsibility that lies on with the individual, the emphasis placed on performance vs. learning, the relative emphasis on single-loop and double-loop learning, the quantity of information, and the extent of participation from members at different levels in the organization [34].

Successful story of integrating learning in xxx

Example here…

Implications

Relevance to PPPM

Having organizational learning can highly benefit all three levels of management. WRITE MORE ABOUT WHY.

Project management concerns creating deliverables, either through independent projects or projects that are part of a program. Projects are well defined in terms of time scope, budget, etc.

Program management concerns creating benefits, and therefore requires active coordination to create a desired outcome. Programs can consist of several projects and can have multiple deliverables, but there is a strong mutual dependence. Managing programs requires a focus on benefits, capabilities and environment.

Portfolio management goes deeper and is about achieving long term strategic goals. Managers continuously monitor changes in the internal and external environment, to properly adjust priorities of projects and programs.

But developing into a learning organization is not done overnight. To be successful requires commitment and management process that evolve slowly and staidly over time. Harvard suggests a few simple steps to becoming a learning organization [35]:

- 1 Foster an environment that is conductive to learning. Though it might be challenging to take the time in an organization, there needs to be time for reflection and analysis. Managers needs to let the employees take that time, and employees needs to understand the productiveness and use the time wisely. Training in brainstorming, problem solving, evaluating experiments, and other core learning skills is therefore essential.

- 2 Open boundaries and simulate exchange of ideas. Boundaries isolate people and groups and inhibit the flow of important information. Opening the boundaries can be done through conferences, meetings and project teams.

- 3 Create learning forums, which are programs or events with explicit learning goals. These can take forms of large, cross-funcional delivery systems, internal benchmarking reports (identify and compare the best activities in the organization), study missions, and symposiums that brings together customers, suppliers, experts and internal groups to share ideas and learn from each other.

Crucial Steps in Becoming a Learning Organization (https://www.safaribooksonline.com/blog/2015/12/23/building-learning-organization/)

While there is no single way to grow a learning organization, there are a number of common strategies and actions the world’s most successful learning organizations have adopted and developed. Here are a handful of the 16 steps in building a learning organization that Marquardt details in the last chapter of his book:

- Commit to becoming a learning organization.

- Form a powerful coalition for change.

- Connect learning with business operations.

- Establish corporate-wide strategies for learning.

- Extend learning to the whole business chain.

References

- ↑ John Hayes, The Theory and practice of change management, ch. 29

- ↑ https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

- ↑ https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

- ↑ https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

- ↑ Tonnquist, Bo & Hørlück, Jens, Project Management - a complete guide, 2009, ch. 15

- ↑ http://www.thechangeforum.com/Learning_Disciplines.htm

- ↑ Senge, P. M. (1990). The art and practice of the learning organization. The new paradigm in business: Emerging strategies for leadership and organizational change

- ↑ Senge, P. M. (1990). The art and practice of the learning organization. The new paradigm in business: Emerging strategies for leadership and organizational change

- ↑ http://www.thechangeforum.com/Learning_Disciplines.htm

- ↑ http://www.thechangeforum.com/Learning_Disciplines.htm

- ↑ http://www.thechangeforum.com/Learning_Disciplines.htm

- ↑ http://www.thechangeforum.com/Learning_Disciplines.htm

- ↑ Senge, P. M. (1990). The art and practice of the learning organization. The new paradigm in business: Emerging strategies for leadership and organizational change

- ↑ http://www.thechangeforum.com/Learning_Disciplines.htm

- ↑ Michael J. Marquardt, Building the Learning Organization

- ↑ Michael J. Marquardt, Building the Learning Organization

- ↑ Tara Fenwick, University of British Columbia, Understanding Relations of Individual-Collective Learning in Work: A Review of Research

- ↑ Tara Fenwick, University of British Columbia, Understanding Relations of Individual-Collective Learning in Work: A Review of Research

- ↑ http://www.knowledge-management-tools.net/different-types-of-knowledge.html

- ↑ http://www.knowledge-management-tools.net/different-types-of-knowledge.html

- ↑ Michael J. Marquardt, Building the Learning Organization

- ↑ Michael J. Marquardt, Building the Learning Organization

- ↑ https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

- ↑ http://www.knowledge-management-tools.net/different-types-of-knowledge.html

- ↑ John Hayes, The Theory and practice of change management, ch. 29

- ↑ Zedtwitz, Max (2003), Post-Project Reviews in R&D

- ↑ Zedtwitz, Max (2003), Post-Project Reviews in R&D

- ↑ Zedtwitz, Max (2003), Post-Project Reviews in R&D

- ↑ Zedtwitz, Max (2003), Post-Project Reviews in R&D

- ↑ Zedtwitz, Max (2003), Post-Project Reviews in R&D

- ↑ Tidd, J. and Bessant, J. (2013). Managing Innovation – Integrating Technological, Market, and Organizational Change. Wiley, 5th edition, Ch. 3

- ↑ http://smallbusiness.chron.com/critical-success-factors-learning-organizations-48490.html

- ↑ Marsick, Victoria, Learning Organizations

- ↑ Marsick, Victoria, Learning Organizations

- ↑ https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

Cite error:

<ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found