Decision tree

(→Risk Response Analysis) |

(→Risk Response Analysis) |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

* '''Accept''' the risk. If the risk is accepted a response to the risk event occurring should be planned.<br> | * '''Accept''' the risk. If the risk is accepted a response to the risk event occurring should be planned.<br> | ||

| − | * '''Externalise''' the risk. | + | * '''Externalise''' the risk. By contracting out the source of the risk down the supply chain of the project structure, the sub-contractor |

| + | |||

| + | as discussed in section 7.6.This should only be done when the agent is in a better position to manage the risk than the principal, because of having either more information or greater managerial capability. Externalizing risk to an agent which does not have greater capabilities is folly and generates the secondary risk of the agent failing to meet commitments, and thereby effectively handing the risk back to the principal.The extreme case here is when the agent is bankrupted by the occurrence of the risk event. <br> | ||

* '''Mitigate''' the risk by changing the project mission or scope so as to minimise the probability of the risk event occurring.This is frequently the most appropriate response to identified risk sources, and a very good example of why risk man- agement needs to start very early in the project life cycle. <br> | * '''Mitigate''' the risk by changing the project mission or scope so as to minimise the probability of the risk event occurring.This is frequently the most appropriate response to identified risk sources, and a very good example of why risk man- agement needs to start very early in the project life cycle. <br> | ||

* '''Insure''' or hedge against the risk where this is possible.With low-probability rare catastrophes beyond the control of the actors – such as a fire – insurance is usually possible. Where the risks are purely financial and spread across a large number of decisions, portfolio management techniques such as taking options to hedge losses are appropriate. <br> | * '''Insure''' or hedge against the risk where this is possible.With low-probability rare catastrophes beyond the control of the actors – such as a fire – insurance is usually possible. Where the risks are purely financial and spread across a large number of decisions, portfolio management techniques such as taking options to hedge losses are appropriate. <br> | ||

Revision as of 10:18, 22 September 2017

Abstract Decision Tree as a tool in Risk Management. [1]

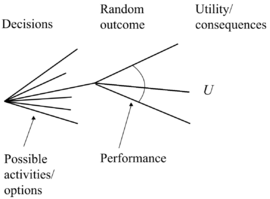

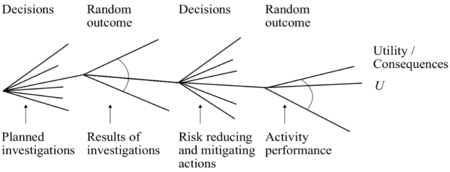

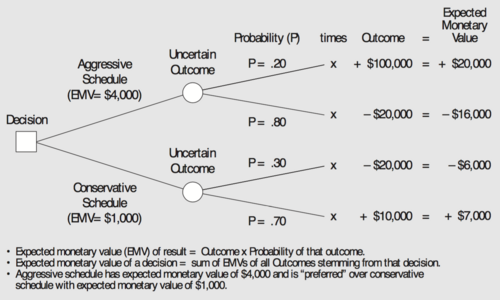

When the risks have been identified and the respective impacts and probabilities have been investigated, the decision whether to insure, mitigate, accept or externalise the risk in question will result in different possible outcomes with different probabilities and consequences. From these different branches other risk decisions will be made, and in the end a decision tree with all the possible different paths to what risks will be managed and how, will be established.

This wiki article investigates how the decision tree works as a tool in risk management, what the benefits are and what barriers are related to this tool.

1. The Decision Tree Concept

2. Applying the Decision Tree to Project Management

3. Other Risk Management Tools Involved

4. Benefits and Possibilites

5. Limitations and Barriers

6. Conclusion

7. References

8. Annotated Bibliography

Writer: Frederik Lind, s133570

Contents |

Initial Steps to Decision Making

Risk Identification

The identification of risks is a process that must begin early in the project during the planning phase and it must be done thoroughly to mitigate potential delays, change of scope, budget overruns and quality loss.[2]

While the definition of the term risk involves only the possibility of experiencing unfavorable events, risk identification within the project context however both includes the opportunities (positive outcomes) and the threats (negative outcomes).[3]

It is practically impossible to identify all risks before they occur, however it is possible to map an extensive majority through a combination of a number of identification methods.

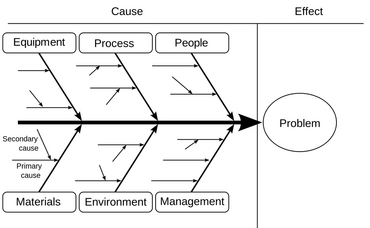

A common first step to identifying risks is to organize the possible risks in branches of causes, Figure 1.

A list of risks can be gathered through brainstorming in collaboration with the project team, experts and stakeholders by focusing on what possible events and their sources within each branch that will affect changes in scope, cost, time and quality of the outcome of the project.[4]

Risk Assessment

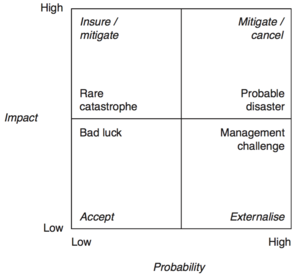

The next step is to assess the potential risks where the goal is to define the consequence and likelihood ranges for each risk source in collaboration with the stakeholders. A tool to visually map the respective probabilities and impacts for each risk and to get an immediate overview of desired response approach is to apply the Probability/Impact Matrix, Figure 2.[1]

The impact of a threat or opportunity occurring will always be associated with a direct or an indirect increase or decrease in cost for the project. The cost related to each consequence must be estimated and registered.

When the probabilities and levels of impact have been evaluated, the planning team should be divided into different field-specific sub-groups to which the respective related risks should be assigned for possible response investigation.[6]

Risk Response Analysis

The assigned sub-groups will then identify any possible actions to prevent risks and to enhance opportunities.[6]

Different response options are often available for each risk source, and the angle of attack to construct the final list of approaches for all risks can be inspired by the Probability/Impact Matrix, Figure 2. The response approach consists generally of four pillars: accept, externalise, mitigate and insurance against the risk. A fifth immediate option is to delay the response decision until more information is available.[5]

- Accept the risk. If the risk is accepted a response to the risk event occurring should be planned.

- Externalise the risk. By contracting out the source of the risk down the supply chain of the project structure, the sub-contractor

as discussed in section 7.6.This should only be done when the agent is in a better position to manage the risk than the principal, because of having either more information or greater managerial capability. Externalizing risk to an agent which does not have greater capabilities is folly and generates the secondary risk of the agent failing to meet commitments, and thereby effectively handing the risk back to the principal.The extreme case here is when the agent is bankrupted by the occurrence of the risk event.

- Mitigate the risk by changing the project mission or scope so as to minimise the probability of the risk event occurring.This is frequently the most appropriate response to identified risk sources, and a very good example of why risk man- agement needs to start very early in the project life cycle.

- Insure or hedge against the risk where this is possible.With low-probability rare catastrophes beyond the control of the actors – such as a fire – insurance is usually possible. Where the risks are purely financial and spread across a large number of decisions, portfolio management techniques such as taking options to hedge losses are appropriate.

- Delay the decision until more information is available.This is frequently used, particularly in relation to risks generated by the regulatory system.

Every preventive or enhancing action or lack hereof is associated with a direct cost which

Decision Tree - Treating Risks

The Concept

yes yes this is math

Usability for Project, Programme and Portfolio Risk Management

Applying the Decision Tree

Pre and Posterior Decision Making

Benefits and Possibilites

Limitations and Barriers

Conclusion

Annotated Bibliography

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Geraldi, Joana and Thuesen, Christian and Stingl, Verena and Oehmen, Josef (2017) How to DO Projects? A Nordic Flavour to Managing Projects: DS-handbook, Version 1.0, Publisher: Dansk Standard

- ↑ Jutte, Bart (2016) 10 GOLDEN RULES OF PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT, https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/10-golden-rules-of-project-risk-management.php [retrieved Sep 20th 2017], Publisher: Public Smart.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Duncan, William R. (1996). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Project Management Institue: PMI Standards Committee.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Geraldi, Joana and Thuesen, Christian and Stingl, Verena and Oehmen, Josef (2017) Risk identification - basic methods, http://www.doing-projects.org/Conceptbox/Risk-identification-basic-methods [retrieved Sep 20th 2017], Publisher: Doing-Projects.org.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Winch, Graham M. (2010) Managing Construction Projects - An Information Processing Approach, 2nd Edition, Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wrona, Vicki (2015) YOUR RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS: A PRACTICAL AND EFFECTIVE APPROACH, https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/your-risk-management-process-a-practical-and-effective-approach.php [retrieved Sep 22nd 2017], Publisher: Public Smart.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Faber, Michael Havbro (2010) Statistics and Probability Theory - In Pursuit of Engineering Decision Support, Publisher: Springer International Publishing AG.