The Framework of Project Governance

(→References) |

(→References) |

||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

<ref name="PMBOK">Project Management Institute. (2013). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). 5th ed. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute. </ref> | <ref name="PMBOK">Project Management Institute. (2013). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). 5th ed. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute. </ref> | ||

| − | <ref name="HOW">Geraldi, J. Thuesen, C. Oehmen, J. and Stingl, V. (2017). ''How to DO projects. A Nordic flavour to managing projects''. Göteborg: Danish Standards Foundation, | + | <ref name="HOW">Geraldi, J. Thuesen, C. Oehmen, J. and Stingl, V. (2017). ''How to DO projects. A Nordic flavour to managing projects''. Göteborg: Danish Standards Foundation, p.99. </ref> |

<ref name="PRINCE2"> Great Britain. Office of Government Commerce. (2009). Managing successful projects with PRINCE2. TSO. </ref> | <ref name="PRINCE2"> Great Britain. Office of Government Commerce. (2009). Managing successful projects with PRINCE2. TSO. </ref> | ||

Revision as of 14:59, 25 February 2018

Contents |

Abstract

Project governance is the establishment of organizational comprehension and circumstances under which delivering and organizing successful projects.[1] Establishing project governance for all projects is an essential element in defining responsibilities and accountabilities in organizational control. Project governance provides a framework for consistent, robust and repeatable decision making. Hence, this offers a structured approach towards assuring businesses to conduct project activities, "business as usual" activities, as well as organizational changes.[2] Project success is the primary objective of all projects; thus the systematic application of suitable methods and a stable relationship with project governance is of vital importance to reach an optimal project success.[3] According to the research article "Project Governance – The Definition and Leadership Dilemma"; a majority of authors on project governance have a background in project management, where they attempt to create the project governance framework through a bottom-up approach. Due to a variety of projects in the industry, the range of stakeholders interest, different values and types, and complexity spectrum, the bottom-up strategy has its limitations when providing concise guidance to managers when executing and enforcing project governance.[4] Based on these observations, the objective of this article sections into three parts; firstly the big idea of project governance will be described including the main pillars of project governance and its core principles. Secondly, three different approaches towards project governance will be identified along with the core principles. Lastly, the limitations concerning the different approach towards project governance will be analyzed.

The Big Idea

Project Stakeholders and Governance

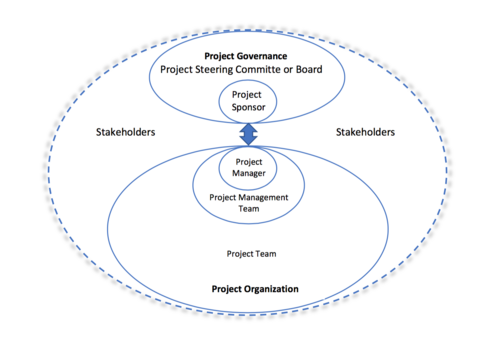

According to the PMBOK® guide, "a stakeholder is an individual, group, or organization who may affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome of a project." Stakeholders are often interested in the project or actively involved in it which may have a positive or negative effect on the performance or completion of the project. Various stakeholders may have competing expectations which could create conflicts within the project. Project governance is the alignment of the project with stakeholders' requirements or goals which is a vital element to the successful management of stakeholder engagement and the execution of organizational goals. Project governance enables organizations to consistently manage projects, maximize the value of project outcomes and align the projects with business strategy. It presents a framework in which the project manager and sponsors can make decisions that satisfy stakeholder needs and expectations, as well as the organizational strategic objectives.[6] Figure 1 provides an overall view of the project stakeholders which are divided into three groups, the project governance stakeholders, the project organization stakeholders and the additional stakeholders. For the purpose of this article, the primary focus will be on the project governance stakeholders.

Introduction to Project Governance

The purpose of the framework of project governance, according to the PMBOK® guide, is to provide structure, processes, decision-making models and tools for the project manager and team members to manage a project while supporting and controlling the project for successful delivery.[6] According to Patric S. Renz, project governance is defined as "a process-oriented system by which projects are strategically directed, integratively managed, and holistically controlled, in an entrepreneurial and ethically reflected way. Appropriate to the singular, time-wise limited, interdisciplinary, and complex context of projects."[7] The three pillars of project governance are Structure, People, and Information. The project governance structure refers to the formation of the governance committee, project steering committee or board. People participating in the committees are the ones that decide the nature of projects and its effective structure. Information regarding the project is escalated by the project manager to the governance committee, which includes regular project reports, issues or risks.[2] Effective governance of project management ensures that the project portfolio of an organization is aligned to its objective, delivered efficiently and is sustainable. It also supports the corporate board and project stakeholders receiving timely, relevant and reliable information.[8] The project governance framework provides a comprehensive and consistent approach towards controlling the project and assuring its success by documenting, defining and communicating project activities. It includes a framework for making project decisions which include defining roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities for project success as well as determining the effectiveness of the project manager.[6] Additionally, the framework of project governance involves documented policies, procedures, standards and authorities. As illustrated in Figure 1, the project sponsor is needed in the project governance and is the person who authorizes the project, makes executive decisions, solves problems and conflicts beyond the authority of the project manager. Additionally, the project steering committee or board, which provide senior level guidance to the project, are also involved in the project governance, which can be seen in Figure 1. Examples of the elements of the project governance framework includes the following:[6][9]

- Project success and deliverable acceptance criteria;

- Special process to identify, escalate, and resolve issues that arise during the project;

- Established relationship between the project team, organizational groups, and external stakeholders;

- Project organizational chart which identifies project roles;

- Procedures and processes for communicating information;

- Project decision-making processes;

- Guidelines for the alignment of project governance and organizational strategy;

- Project life-cycle approach;

- Specific process for stage gate or phase reviews;

- Process special for review and approval of budget changes, scope, quality and schedule that are beyond the authority of the project manager;

- Process to align internal stakeholders with project process requirements.

It is the responsibility of the project manager and the project team to decide the appropriate method of executing the project within the constraints listed above, as well as the additional limitation of time and budget. While the project governance framework includes the activities in which the project team performs, the team is responsible for planning, executing, controlling, and closing the project. Included in the project governance framework is the decision regarding who will be involved in the project, escalation procedure, what resources are required and the overall approach towards completing the project. Additionally, the consideration of whether more than one project phase will be involved and if so, what the life-cycle of the project should be.[6]

The Framework of Project Governance

To reach a deeper understanding of how the framework of project governance is conducted, this chapter will be sectioned into three parts. Firstly, the core principles of project governance will be thoroughly explained. Secondly, the illustration of the project governance model will be introduced. Lastly, three different approached towards project governance will be demonstrated. The stakeholder groups within project governance will be the primary focus of this framework which includes the definitions of their roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities.

Core Principles

- Principle 1

The first principle of effective project governance is the concept of a single point of project's accountability. Regarding project success, it is required to have a single point of accountability. However, the nomination of someone to be accountable is not enough, the correct person must be made accountable. This person should fulfill the requirement of having sufficient authority within the organization which assures the empowerment of making necessary decision to reach a project success. Additionally, this person should have the correct knowledge within the organization to be held accountable for the actions and decisions made for the project. Without a clear understanding of who assumes accountability for the projects' success, there is no clear leadership. Thus, no one person drives the solution of difficult issues which all projects deal with at some point in their life-cycle.[2]

- Principle 2

This principle argues that the project owner should be independent of the asset owner, the service owner or other stakeholder groups. The tool of ensuring that projects meet customer and stakeholder needs, while optimizing the value of money, is to choose a project owner who is a specialist and not a stakeholder in the project. This way, the project owner engages under clear terms that outline the organizations' key result areas and the organization's sense of the key project stakeholders. In some cases, organizations establish governance projects committee, which identifies the occurrence of projects and selects project owners a the beginning of the project's life-cycle. Additionally, this committee establishes project councils which create the foundation of customer and stakeholder engagement, as well as establishing the key result areas for a project consistent with the organization's values and oversees the project performance. [2]

- Principle 3

The third principle claims that the project governance should separate the stakeholder management from the project decision-making activities. The effectiveness of the decision-making committee is often connected to its size. When project-decision forum grows in size they tend to change into stakeholder management groups. Consequently, the detailed understanding of each person of the issues relating to the project reduces. Furthermore, everyone involved in the decision-making will not have the same level of understanding of the issues and therefore, time is wasted bringing everyone up to speed on a particular issue. Hence, large project committees are established more as a stakeholder management forum rather than project decision-making forum. This creates an issue when a project depends on the committee to make timely decisions. That is why the stakeholder management needs to be separated from the project decision-making activities to reach a successful project.[2]

- Principle 4

The main focus of this principle is to ensure separation between project governance and organizational governance structures. The establishment of project governance structures needs to be executed due to the fact that organizational structures do not provide the necessary framework to deliver a project. The characteristics of projects are speed and flexibility in its decision making and the organizational structure does not support that. The organizational structure has requirements of reporting and stakeholder involvement. However, by adopting this principle of separation, it will result in reducing multi-layered decision making, time delays, and inefficiencies. This ensures that project decision-making is executed in a timely manner. Thus, the established project governance framework for a project needs to be separated from the organizational structure.[2]

- Principle 5

This is a complementary governance principle which lists various elements that are of great importance for the governance of project management. The board's responsibilities include the definition of roles, responsibilities, and performance indicators for the governance of project management. Arranging disciplined governance is supported by appropriate methods and the project control is applied throughout the project life-cycle. An important responsibility of the board is the establishment of a coherent and supportive relationship between the overall business strategy and the project portfolio. It is expected that projects should have an approved schedule containing authorization points in which the business case is reviewed and approved, and decisions made are recorded and communicated. As illustrated in principle 1, people with authority should have sufficient representation, competence, and resources to enable appropriate decisions. There should be clearly defined criteria for reporting project status and for the escalation of risks and issues to the required organizational levels. Additionally, it is important for the organization to foster a culture of improvement and internal disclosure of project information.[2]

- Principle 6

This last principle focuses on multi-owned projects, which is defined as being a project where the board shares ultimate control with others owners. In this case, a formal governance agreement needs to be established with a single point of decision-making for the project. Additionally, a clear allocation of authority which represents the project to owners, stakeholders, and third parties. Regarding the business case, it should include definitions of project objectives, the role of owners, as well as their inputs, authority, and responsibility. The leadership of the project should escape synergies that arise from multi-ownership and should manage potential sources of conflict or inefficiency. A formal agreement is required which defines the processes and consequences for assets and owners when a material change of ownership is considered. It is important that reports during the project and the realization of benefits contain honest, timely, realistic, and relevant data on progress, achievements, forecasts, and risks to establish good governance by project owners.[2]

The Project Governance Model

The project governance model consists of six modules which establish the six key responsibilities. The objective of each key responsibility in each module is outlined. Moreover, a number of particularities shape the context of the key responsibilities. Subsequently, for each key responsibility, a model is developed from theoretical foundations and best practices. [7]

System Management

System management "lays the systemic, and systematic foundation for the understanding and possible influencing of the wider system, and for the managing of the project system. Thus, system management is the most basic key responsibility of project governance." System management is divided into two parts:[7]

- Systemic thinking (the "software")

System thinking is the "philosophy of how to approach a solution to a complex problem." Five characteristics are listed here below:[7]

- Holistic thinking in open system;

- Analytical and synthetical thinking;

- Dynamic thinking in circled processes;

- Thinking in structures and information processes;

- Interdisciplinary thinking.

- A system model (the "hardware")

Systemic thinking allows projects to be constructed according to the specific system circumstances. Also, to be managed efficiently and effectively based on an enhanced system understanding. The six key areas of the system model are listed below:[7]

- Environmental spheres;

- Stakeholders;

- Issues of interaction;

- Structuring forces;

- Processes;

- Modes of development.

Mission Management

The critical responsibility of the mission management is that the governance board directs and controls the strategy, structure and the cultural elements of a project. Hence, the mission management is the representation of the strategic, support, and control roles of governance. Mission management is argued to be the governance function of strategical direction, support, and control of a project and its management. Thus, the primary structuring forces of the mission management are strategy, structure, and culture. Collectively with the governance roles of strategic direction, support, and control, they compose the below matrix.[7]

| Structuring forces/Project governance roles | Strategic direction and support | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy |

|

|

| Structure |

|

|

| Culture |

|

|

Integrity Management

Integrity management provides "an integrated platform to deal with integrity challenges, on a fundamental level as well as on the level of specific integrity issues." A combined approach towards integrity management is suggested, inclusive of Recognition Ethics and Discourse Ethical Guidelines.

- Discourse Ethical Guidelines

The practical value of discourse ethics is in the "normative-critical oriented power of its procedural ideal to the discourse-based clarification of moral questions." Four normative guidelines of discourse ethics will be described here below:

- Communicatively oriented attitude: The phrase "let's agree to disagree" applies here. When people discuss a specific topic, they only argue for claims they truly think are right, they substantiate their claims without reservation and show genuine interest in arriving at a rational outcome.

- Interest for legitimate action: A genuine interest towards the people involved in communicative coordination of their actions, with the goal to legitimize them.

- Differentiated responsibility: A person acting responsibly is when faced up to the demands for justification or solidarity and to all criticism that are affected by this person's intended actions.

- Public binding: To create in each real communication community the best possible organizational conditions, which adjusts on the regulative idea of each ideal communication community.

- Recognition Ethics

This is based on the fact that human beings are dependant upon mutual recognition. People want their loved one to love them, friends and colleagues to recognize them for what they are and do, their employer to honor their achievements etc. Three terms of mutual recognition are mentioned here below:

- Emotional recognition: Takes place among partners, friends, family, and colleagues etc. A non-observation of such recognition represents moral injuries.

- Legal and political recognition: Is represented by "a set of basic rights as human beings and citizens."

- Solidarity: Is recognizing others as a social person "whose capabilities are of basic value for a concrete community."

Extended stakeholder Management

Risk Management

Audit Management

Limitations

Annotated Bibliography

Project Management Institute, Inc. (2013). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) - Fifth edition.: This guide provides relevant theories and concepts related to project management. Moreover, it provides general knowledge about project governance and the main elements of a project governance framework.

Patric S. Renz. Project Governance - Implementing Corporate Governance and Business Ethics in Nonprofit Organizations. Springer (2007)

References

- ↑ Beecham, Rod. (2011). Project Governance, The Essentials. Ely: IT Governance, pp.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Liu, X. and Xie, H. (2014). Pillars and Principles of the Project Governance. Advanced Materials Research,1030-1032(1030-1032), pp. 2593-2596.

- ↑ Deenen, R. (2007). Project governance - phases and life cycle. Management and Marketing.

- ↑ Bekker, M. (2015). Project Governance – The Definition and Leadership Dilemma. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 194, pp. 33-43.

- ↑ Danish Standards Foundation. (2012). International Standard ISO 21500 - Guidance on project management. Danish Standards Foundation.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Project Management Institute. (2013). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). 5th ed. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Patric S. Renz. Project Governance - Implementing Corporate Governance and Business Ethics in Nonprofit Organizations. Springer (2007).

- ↑ Great Britain. Office of Government Commerce. (2009). Managing successful projects with PRINCE2. TSO.

- ↑ Geraldi, J. Thuesen, C. Oehmen, J. and Stingl, V. (2017). How to DO projects. A Nordic flavour to managing projects. Göteborg: Danish Standards Foundation, p.99.