TOC (Theory of Constraints)

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

On the other hand Spearman dives more deeply in the theory and raises some criticism against TOC. | On the other hand Spearman dives more deeply in the theory and raises some criticism against TOC. | ||

The first one is that the theory is not complete. Indeed, according to him: « Despite what its advocates imply, the TOC does not offer a complete management paradigm. There are times when trade-offs must be made and the TOC is hard pressed to provide much assistance in these situations ». <ref> Spearman, M., 1997. On the theory of constraints and the goal system. Production and Operations Management, 6 (1), 28–33. </ref> | The first one is that the theory is not complete. Indeed, according to him: « Despite what its advocates imply, the TOC does not offer a complete management paradigm. There are times when trade-offs must be made and the TOC is hard pressed to provide much assistance in these situations ». <ref> Spearman, M., 1997. On the theory of constraints and the goal system. Production and Operations Management, 6 (1), 28–33. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Conclusion== | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Annotated Bibliography= | ||

| + | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 10:45, 14 March 2022

Contents |

Abstract

The Theory of Constraints (TOC) was introduced in 1984 by Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt in his bestselling novel « The Goal ». It has been developed continuously since then by Dr. Goldratt as well as other contributors and has become a notable method in the world of management.

This theory is a problem-solving management method. TOC is based on an iterative method for improvement. It considers every system as a chain of activities that operates one after another and hypothesizes that this chain is not stronger than its weakest link. Indeed, among these activities, one acts as a constraint upon the entire system, i.e. the weakest link. These limiting factors or constraints, also referred as bottlenecks, are slowing down the process of a system.

The overall goal is to eliminate these constraints in order to enhance performance. To do so, five steps have been defined as the key steps of all the methods derived from TOC. These Five Focusing Steps are : Identify, Exploit, Subordinate, Elevate and Warning.

The first application of TOC was for manufacturing but it has evolved and is now applicable for any type of project management. Indeed,

Looking at manufacturing management, the primary methodology used is the DBR, standing for Drum-Buffer-Rope.

On the other hand, for any type of project management, the Critical Chain Project Management) (CCPM) has been developed.

Nowadays, from a project management perspective, multiple tools derived from the TOC have been developed, also known as Thinking Processes (TP). This set of tools embodies the whole TOC and helps identify and manage constraints in projects.

The Theory of Constraints

The Goal

"The Goal : A process of ongoing improvement" [1] is a novel by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox published for the first time in 1984. This novel is focused on manufacturing and is halfway between a fiction and a case study.

The novel’s plot is the following. Alex Rogo is the manager of the UniCo plant. However the plant is currently losing so much money that it will be shut down in three months if he does not take action. In the same week, his wife Julie leaves him because he is spending so many long hours at work.

By accident, Alex meets a long-time friend who has become manufacturing consultant, and enlists his aid. With Jonah’s help, Alex and his staff discover what are the plant’s bottlenecks. Their most expensive numerically controlled machine, the NCX-10 is one of them, and the heat-treat is the other. Until the end of the story, they will spend their time figuring out how to increase the capacity of these bottlenecks and ultimately, how to use the bottlenecks’ production schedule to control the release of material into the plant. With a newfound emphasis on shipping late orders first, they clear their backlog, and go in search of new business. Alex finally saved the plant from being shut down and also saved his marriage.

The power of this novel is in the fact that it helps people without production experiences to understand the realities. It also introduced the Drum-Buffer-Rope (DBR) approach that will be developed later for the time. It then triggered a great interest among academicians, economists and business community and was not about to stop. Indeed, in 1995, The Economist [2] wrote: « The most successful attempt at management-as-fiction is still The Goal. » To this point, the book has been translated into 18 languages and has become a bestseller. [3]

Finally, many re-editions of this novel has been edited by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and other contributors to dive deeper in the different approaches and methods of ongoing improvement implemented in the novel. The Theory of Constraint (TOC) is born from it and a wide set of tools related to it have been developed.

What is a Constraint

A constraint is anything that prevents the system from achieving its goal. There are many ways that constraints can show up, but a core principle within TOC is that there are not great number of constraints. There is only one or a few. Indeed the principle behind TOC is that a chain is no stronger than its weakest link, i.e. the constraint in the system. [4] Constraints can be separated in two types of constraints. Internal constraints exists when the market need is higher than what can be produced. Three types of internal constraints can be identified. The first ones are equipment constraints, when the equipment or how it is used prevents the system from producing than the market is asking for. The second type of internal constraints are people.The lack of skills, the mental models and behaviors can also lead to less efficiency in the production. Finally policies are the last ones. Written or unwritten policies, management decisions or business cultures can also slow down the system. On the other hand, external constraints appear when the market can not provide the raw material to produce goods or when it is not ready to absorb the quantity of goods produced by the system and then needs more demand. [5] Constraints have also to be differentiated from breakdowns. Indeed, many incidents can occur with equipments, people and policies but they are not taken into consideration in TOC.

The theory of constraints also provides a system to measure and control them. It is based on three criteria : throughput, inventory and operating expense. Throughput is the sales’ cash flow, inventory is the money invested in goods that will be used to produce final products and operational expense is the money invested to turn the inventory into throughput. [6]

The constraint is the limiting factor that is preventing the organization from getting more throughput. If its capacity is improved so it is no longer the system's limiting factor, it is said to "break" the constraint. The limiting factor is now some other part of the system, or may be external to the system.

The 5 Focusing Steps

Considering the TOC philosophy, performance improvement efforts are focused on the system’s constraints and is referred as « process of ongoing improvement ». This focus is done through a set of five steps also know as « Five focusing steps » developed by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox that are systematic and can be used with any type of system. They are the key steps to developing different application of TOC that will be reviewed in the next section. The five focusing steps are:

• Identify the system’s constraint(s): whether they are external, equipment, people or policy constraints. Since constraints are limiting the global performance, it is the first step to achieve improvement.

• Decide how to exploit the system’s constraint(s). The objective here is to make the constraint as effective as possible with what is currently available. This step is mostly used when dealing with physical constraints.

• Subordinate everything else to the decisions made in step two. Everything else is all the non-constraints, i.e. activities that have more capacity than the actual constraint. The point of subordinating every other decisions is that any decision on non-constraints will generate necessary extra work load that the constraint can currently not deal with. Indeed the capacity of the system is limited by the constraint, not by the non-constraints Thus the priority is the take action on the constraint first.

• Elevate the system’s constraint(s). If the improvement is no longer possible with the two previous steps, the next step is to put extra efforts on the constraints and elevate its capacity. Extra efforts to enhance capacity require investment and require time. As the performance improves, to potential of non-constraint can be exploited and it it will increase the overall system performances.

• If the constraint is broken, return to the first step. Once capacity is added to the existing constraint, the constraint might be broken. It implies that there is a new constraint whether it is in the system (internal) or not (external). New rules will be applied to deal with this one as non-constraints are also different. This step closes the loop of the five focusing steps and allows to get in an ongoing process of improvement.

Application

From Manufacturing with DBR...

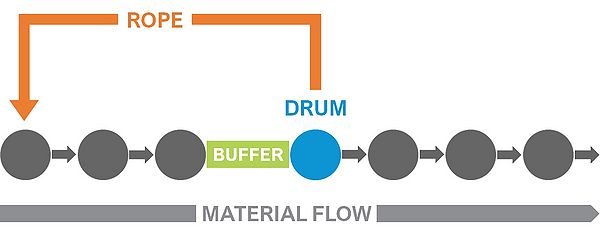

One of the main methodology developed around Goldratt’s novel is the Drum-Buffer-Rope (DBR) approach. It was developed for manufacturing project and is used during the « Exploit » and « Subordinate » focusing steps from the previous section. DBR is a production scheduling methodology that controls the release of jobs from the system according to the constraint capacity. The three different components of DBR are the following [7]:

• The Drum is the exploitation of a constraint, includes detailed schedule. Since the constraint is limiting the performance, it gives the pace of the production as drums do.

• The Buffer is the protection time that prevents the system from eventual disruptions as absenteeism, raw material delivery delay or other breakdowns at non-constraint level. Buffers are measured in time units. They reflects the capacity level of non-constraint resources and determines the time needed to for these latter to catchup in case of disruption. The use of time buffers to improve throughput is often referred as buffer management.

•Rope is a communication mechanism between critical control points that will force the different parts to synchronize at the pace of the drum. Based on the feedback provided, order release aligns the input of work with the output rate of the constraint. A maximum limit on the number of jobs released to the bottleneck but not yet completed is established and a job is released whenever the number of jobs is below the limit

Three steps are required to schedule DBR [8]. The first one is to schedule the constraint and exploit it according to the objectives. The second is to determine the buffer sizes and the final one is to derive the materials release schedule according to the two previous steps.

...to Project Management with CCPM...

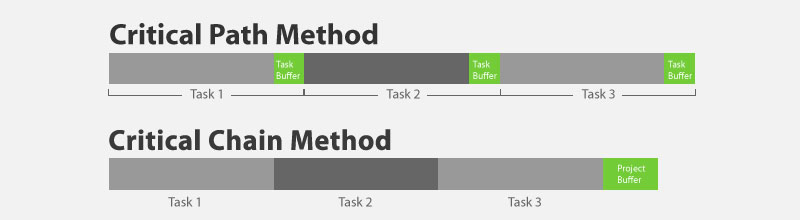

In project management, the critical path is the longest sequence of tasks that must be completed to complete a project. The tasks on the critical path are called critical activities because if they're delayed, the whole project completion will be delayed.

Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM) is based on methods and algorithms derived from Theory of Constraints. Eliyahu M. Goldratt extended his TOC’s application to project management with CCPM [9]. The idea of CCPM was introduced in 1997 in his book, Critical Chain. Having researched reasons for project failure, Goldratt identified the main ‘constraint’ to project success as the ‘sequence of dependent events that prevents the project from being completed in a shorter interval’.

The critical chain approach differs from the critical path approach where the critical path is defined as the longest sequence of tasks that must be completed to complete the project. Goldratt argues that safety time and its use is of crucial importance in project management. Critical path is criticized to deal with uncertainty in the same way for all activities, whether or not they are on the critical path. Unlike the critical path where safety time is added at the end of each activity, the critical chain aggregates these safety times at the end of the chain as a project buffer. Activities then start at the latest and the project buffer ensures that the chain’s schedule is respected.

To establish the critical chain methodology, activities from both the critical chain and non-critical chains are listed together with their logical dependencies and an estimate of their duration [10].

Feeding buffers are added to a non-critical chain so that any delays on a non-critical chain don’t affect the critical chain. They are inserted between the last task on a non-critical chain and the critical chain. The total time for the critical path is then reviewed from the perspective of the resource requirements of the activities. Resource buffers are set on the critical chain to ensure appropriate resources (people, equipment) are available throughout the project when needed. These resources are commonly known as critical resources.

The schedule is then revised knowing that every task owners is more likely to over-estimate the duration of their tasks. Thus the time allocated for their tasks is divided by two which is supposed to be the most accurate estimation. Then some extra time is allocated at the end of the chain as the project buffer. Goldratt estimates that the allocated time for the buffer project should be one half of the total time of the activities revised duration [11].

By doing so, task owners are only focused on completing the task properly in the right time. There is no lost time in between the activities. The project still protects the chain from being completed in time but it is more likely to be completed in less time than would have been the critical path [12].

...to the the Thinking Processes.

TOC has evolved through the years, from a manufacturing management method, it has become a methodology now regarded as a systems methodology applicable in any type of project. Through its tools for convergent thinking and synthesis, the Thinking processes (TP), which underpin the entire TOC methodology, help identify and manage constraints and guide continuous improvement and change in organizations. [13] Originally conceptualized by Goldratt, the TOC thinking processes approach to the management of change involves answering three basic questions: ‘What to change?’, ‘What to change to?’ and ‘How to cause the change?’. In order to answer these three questions, TOC TP reflects a systems-based managerial approach that involves five basic logic tools. These tools use either sufficiency or necessity logic to help managers understand why desirable or undesirable situations occur, to evaluate the impact of interventions designed to eliminate undesirable conditions and to offer guidance on how to manage the change required for improved performance. The five tools or logic diagrams are [14]:

•Current reality tree (CRT): designed to help identify the system constraint responsible for a majority of undesirable effects (UDE’s). It is a particularly effective tool if the constraint is a policy.

•Evaporating cloud (EC) (Kim): designed to address conflict or dilemma situations by diagramming the logic behind the conflict and methodically examining the assumptions behind the logic.

•Future reality tree (FRT): designed to see how changes would affect current reality. Its primary purpose is to evaluate logically the effectiveness of new ideas or injections before they are actually implemented.

•Prerequisite tree (PRT): designed to describe the necessary condition relationships require to accomplish the desired objectives.

•Transition tree (TT): designed to develop a detailed step-by-step set of actions that need to be completed in order to implement change within an organization.

The ancillary tool is called a negative branch reservation (NBR) and is aimed at document ing potentially undesirable effects of change introduced in the FRT.

Thinking processes are then a set of tools designed to help managers to go through the steps of initiating and implementing a project in a logical flow.

Limitations

TOC complexity

One of the first limitation of the TOC is brought by Husby (2007) in his analyse of both Six Sigma and TOC approaches. Indeed, he relates that « the unique language and thinking process of TOC aren’t easy to master, and that can create a barrier to effective use across the enterprise. The problem-solving process uses an “intellectual” language requiring well trained experts for effective application. TOC’s process and language complexity, along with its top-down nature, aren’t conducive to engaging all team members." [15]

Is it a theory?

On the other hand Spearman dives more deeply in the theory and raises some criticism against TOC. The first one is that the theory is not complete. Indeed, according to him: « Despite what its advocates imply, the TOC does not offer a complete management paradigm. There are times when trade-offs must be made and the TOC is hard pressed to provide much assistance in these situations ». [16]

Conclusion

Annotated Bibliography

References

- ↑ Goldratt, Eliyahu M.; Cox, Jeff (1984). The Goal. Gower Publishing. ISBN 978-0-566-02683-6.

- ↑ The Economist, 1995. Tales out of business school. 21 January, 334, 63.

- ↑ Ronald S. Tibben-Lembke (2009) Theory of constraints at UniCo: analysing TheGoal as a fictional case study, International Journal of Production Research, 47:7, 1815-1834, DOI: 10.1080/00207540802624003

- ↑ Cox, J. F., & Schleier, J. G. (2010). Theory of constraints handbook. Theory of Constraints Handbook (pp. XXXVI, 1175 S. (unknown). McGraw-Hill Professional.

- ↑ John Blackstone (2010) Theory of Constraints. Scholarpedia, 5(5):10451.

- ↑ Goldratt, Eliyahu M. (1998). Essays on the Theory of Constraints. [Great Barrington, Massachusetts]: North River Press. ISBN 0-88427-159-5.

- ↑ Guide VDR. Scheduling using drum-buffer-rope in a remanufacturing environment. International Journal of Production Research. 1996;34(4):1081. doi:10.1080/00207549608904951

- ↑ Schragenheim, E., & Ronen, B., 1990, Drum-buffer-rope shop floor control, Production and Inventory Management Journal, 31(3), 18-23

- ↑ Goldratt, E. M. (1997). Critical chain (pp. 246 s.). The North River Press,

- ↑ (2014). Critical Chain Project Management. In A Handbook for Construction Planning and Scheduling (eds A. Baldwin and D. Bordoli). https://doi-org.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/10.1002/9781118838167.ch5

- ↑ Yongyi Shou and K. T. Yao, "Estimation of project buffers in critical chain project management," Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology. ICMIT 2000. 'Management in the 21st Century' (Cat. No.00EX457), 2000, pp. 162-167 vol.1, doi: 10.1109/ICMIT.2000.917313.

- ↑ Yongyi Shou and K. T. Yao, "Estimation of project buffers in critical chain project management," Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology. ICMIT 2000. 'Management in the 21st Century' (Cat. No.00EX457), 2000, pp. 162-167 vol.1, doi: 10.1109/ICMIT.2000.917313.

- ↑ Kim, Seonmin, Victoria Jane Mabin, and John Davies. "The theory of constraints thinking processes: retrospect and prospect." International Journal of Operations & Production Management 28.2 (2008): 155-184.

- ↑ Scoggin, J. M., Segelhorst, R. J., & Reid, R. A. (2003). Applying the TOC thinking process in manufacturing: A case study. International Journal of Production Research, 41(4), 767–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020754031000065557

- ↑ Husby, P. (2007). Competition or Complement: Six Sigma and TOC. Material Handling Management, 62(10), 51–55.

- ↑ Spearman, M., 1997. On the theory of constraints and the goal system. Production and Operations Management, 6 (1), 28–33.