Stakeholder Management as a Contractor

(→Power/Interest Matrix) |

|||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

Finally, the stakeholders in the ''manage closely''-category are the key players, such as financiers, the client, and even the management contractor. They all have strong power and very high interest in the project, and should all be managed closely during the duration of the project/program. | Finally, the stakeholders in the ''manage closely''-category are the key players, such as financiers, the client, and even the management contractor. They all have strong power and very high interest in the project, and should all be managed closely during the duration of the project/program. | ||

| − | For an in-depth explanation of other methods used for Stakeholder Management, the following article is recommended: [[Stakeholder Analysis]] | + | For an in-depth explanation of other methods used for Stakeholder Management, the following article is recommended: [[Stakeholder Analysis]]. |

=== Limitations of Stakeholder Management === | === Limitations of Stakeholder Management === | ||

Revision as of 17:28, 28 September 2015

A stakeholder is an entity that can affect a project or be affected by the project itself; thus a stakeholder may have an interest in the outcome and the management of a project. Therefore stakeholder management is essential for project, program and/or portfolio management. Managing stakeholders includes identifying, analysing and mapping the stakeholders. Once the stakeholders have been identified and mapped, they can be managed and engaged accordingly.

This article aims to discuss the crucial concept of managing your stakeholders in a construction project, and will reflect on the principles and methods used in both contracting and in supply chain management (SCM). The article will draw parallels between SCM and contracting concepts, finding similarities, limits and differences from a contracting perspective. The purpose of this article is to analyse the stakeholder management when contracting a large construction program, and reflect upon the similar methods used when managing a supply chain within an organisation.

Contents |

General

The term contracting often describes the act of entering a formal and/or legally binding agreement. In civil engineering, management contracting is the agreement that the construction work is carried out by several different work contractors, who are either contracted to the client or a management contractor (main contractor). The various different work contractors may include suppliers, manufacturers, retailers or workers, and it is the job of the main contractor to manage them all and ensure that the project goes according to the project plan. The main contractor is expected to oversee and involve subcontractors and suppliers, along with managing the overall project and the external stakeholders, such as governmental or local institutions.

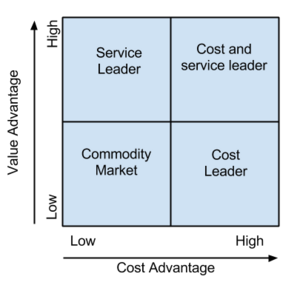

As companies often aim to be succesful, they will seek to achieve a position in the market, where they can offer both a cost advantage and a value/service advantage. As seen on the logistics and competitive advantage matrix[1], it is suggested to have a Cost and Service Leader in order to achieve a competitive advantage in the market. In construction management, the cost and service leader may be responsible for developing a fitting bid for a project, and ensuring that during the project the value created meets the expectations of the client. Obtaining both cost leadership and service leadership, will put an organisation in a leading position within the market. To accomplish this, it is often critical to have an experienced project or program manager leading big projects. Such a leader will often be a management contractor, and he will be responsible for the subcontractors and the flow of resources.

Flow of products, supplies, information, and resources is essential in order to successfully create and plan a project. Logistics provide a solid framework for flow-based plans, such as manufacturing and development facilities. Supply Chain Management (SCM) builds upon this framework, and "seeks to manage upstream and downstream relationships with suppliers and the client, in order to achieve enhanced value in the final market with less cost to the supply chain as a whole."[1] The goal of supply chain management differs from chain to chain, but it could include a wish to reduce buffers in warehousing, by sharing information and co-ordinating the suppliers. The focus of a supply chain is to establish co-operation and trust between suppliers and clients, in order to optimize the final output.

The Management Contractor

A management contractor (main contractor, general contractor) is responsible for the coordination of the construction project, and will oversee the daily progress at the site. The contractor will manage and be responsible for turnkey -, main -, and individual trade contracts[2], and ensure communication between suppliers, traders and the client throughout the course of the project.

- Turnkey Contracts: A turnkey project is a project that is fully functional upon delivery. Thus a turnkey contract is a project that the subcontractor will be fully responsible for, and he "turns over the keys" to the main contractor once the subcontractors job is done..

- Main Contract: A main contract is the contract that binds the main contractor (the management contractor) to the client. The main contractor can make several other contracts, but he has to follow the project's main contract at all times.

- Individual Trade Contracts: The individual trade contractors (subcontractors) are all bound by various contracts with the main contractor. They deliver resources, work, and/or materials to the project and answer directly to the main contractor.

The client employs the contractor after a bidding process, where an estimated price is presented. The price should cover cost of overhead, materials and equipment needed. The client should choose a contractor based price, quality and/or reputation, so it is important for the contractor to have either a value- or cost advantage. During the project, the main contract will transfer the project management from the client to the general contractor. The general contractor will then (depending on the contract) fully manage the suppliers of materials and equipment, as well as labour and services needed for the project. The general contractor may hire subcontractors to deliver turnkey projects, which are fully functional upon delivery. He/she will also be responsible for safety on the construction site, managing personnel, and applying for the necessary permits. In most cases, the management contractor will find himself as a program manager, as he has to oversee many projects performed by subcontractors, along with the overall project of the construction.

The client may choose to coordinate and manage the program themselves, by not hiring a general contractor, but by entering contracts with several individual trade contractors. The client could also choose to split the management of the project by making grouped contracts, which allow related trades to coordinate their work. By using grouped contracts, the client will have fewer contracts to manage contrary to the individual trade contracts.[2] Having a management contractor is often the preferred solution.

Management of a Network

The work of a management contractor can in many ways resemble the work of a supply chain manager, as both are responsible for overseeing a network of connected and interdependent organisations, suppliers, subcontractors and/or resources. This network must be managed in such a way, that the entities work together to manage and improve the flow of materials and information. Often, unlike a supply chain manager, the management contractor works within a finite amount of time. Construction projects have a finite timespan, in which the building must be designed, built and made habitable. A supply chain manager usually has an infinite amount of time, as his work often based on a market pull-strategy and covers several project portfolios at the same time. This means, that if a single project is cancelled or ends, there may still be other projects or programs that are in need of the supply chain. A management contractor therefore needs a different focus than a supply chain manager, and must know exactly how to handle his suppliers and stakeholders, in order to reach the deadline.

Supply chain managers and management contractors use different theories, models and maps to analyse and manage their stakeholders. A handful of these methods will be covered in the following sections. For a more in depth article of the various topics, the following articles are recommended:

- Stakeholder Management: For an overall stakeholder management analysis.

- Stakeholder Analysis: For an in-depth description of stakeholder analysis.

- Stakeholders from a dynamic and network perspective: For an analysis of stakeholders in a network perspective.

Stakeholder Management in Contracting

According to the ISO 21500:2012 standard[3], a stakeholder is defined as: A person, group or organization that has interests in, or can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by, any aspect of the project.

Managing these stakeholders is critical for a construction project, as the project can have both internal and external stakeholders, on either the demand side, the supply side, the public sector and the private sector. All these stakeholders must be managed accordingly, and there are several different methods in doing so. The first step to stakeholder management in both supply chain management and contracting is to do a Stakeholder Analysis, in order to point out the different stakeholders and their attributes. As the stakeholders are often very different and come from different environments, they will need to be managed differently. The stakeholder analysis will provide a solid framework, that can help forming a plan of engagement of the different stakeholders.

Analysis Process

The stakeholders of a project are actors which will incur a direct benefit or loss from the finished project. As a construction project can both create and destroy value, it is important to analyse the various stakeholders that may have an interest in the project. Often it is useful to categorize stakeholders into internal and external stakeholders:

- Internal Stakeholders: These are in legal contract with the client. Examples: The main contractor, turnkey contractors, traders.

- External Stakeholders: These are not in contract with the client, but have an interest in the outcome of the project. Example: The government, the public.

The internal stakeholders can be categorized around the client as wither the demand side or the supply side. The external stakeholders can, likewise, be broken down into private and public actors. An example of possible stakeholders within the various categories can be seen below[4]:

Table 1: Example of Project Stakeholders

| Internal Stakeholders | External Stakeholders | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demand Side | Supply Side | Private | Public |

| Client, Financiers, Client's employees | Architects, Engineers, Trade Contractors | Local residents, NGOs, Landowners | Local Government, National Government, Regulatory Agencies |

Once the stakeholders have been identified and categorized, they should be analysed and explored, in order to determine their interest in the project and their potential influence. The stronger and more interested stakeholders should be managed more closely than less interested and weaker stakeholders. By mapping the stakeholders, a visual presentation of the stakeholders and their strength/interest/influence/power. Once the stakeholders have been found and analysed, they can be managed, engaged, and planned for.

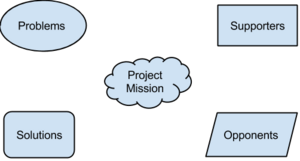

Mapping Stakeholders

In construction projects, the managing contractor often maps the stakeholders in a Winch-Bonke framework[4]. This map focuses on the project mission, and stakeholders can be considered to have a problem with the mission, and to have a solution that will resolve the problem. If the solution is inconsistent with the client's or the main contractor's wishes, then the stakeholders can be defined as being in opposition to the project for as long as the problem is valid. The managing constructor should seek to turn opponents into supporters. This can be done by offering appropriate changes to the project mission, ensuring that both the stakeholder and the client are satisfied. At the same time, the managing contractor should ensure that supporters do not turn into opponents by offering to incorporate their proposed problem solutions.

Mapping the stakeholders is often done before the initiation of the project or program, as the map may uncover some unnecessarily un-cooperative stakeholders. If that is the case, then the management contractor should try to mediate with the stakeholder or, in rare and/or extreme cases, should try to remove the stakeholder if possible, by finding a replacement elsewhere. The map itself may prove useful throughout the project, as it can be used to determine and predict the reactions and actions of the stakeholders in various scenarios.

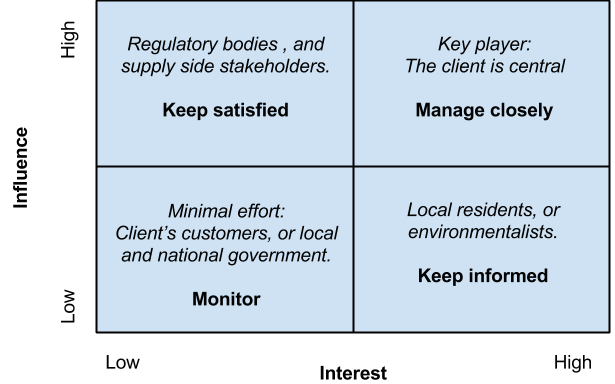

Power/Interest Matrix

Mendelow's Power-interest grid is used in order to classify stakeholders and determine their power in contrast to their interest of a project/program. This mapping method is often used in relation to the Winch-Bonke framework in construction projects, in order to prioritize the stakeholders depending on the two dimensions:[4]

- Power: The power of the stakeholder to influence the project/program definition.

- Interest: The level of interest the stakeholder has in the definition of the project/program.

Stakeholders may be handled differently, as their power and interest may vary greatly. It is, however, important to handle stakeholders correctly, as poor management of stakeholders can have strong consequences of the project, and may even result in a full stop in construction. Certain stakeholders are important and must be overseen at all times during the project, where other stakeholders might need minimal observation.

Stakeholders with low power have only a limited influence on the project. For certain stakeholders in the low-influence low-interest category, a public relations approach may suffice, as it will ensure that those who may be against the project remain in the low-interest and low-power category. Hopefully supporters of the project, may be able to move into the high-interest category. Local residents often have very little influence on the project, but may be very interested in knowing what the construction will do to the surrounding area. They should be kept informed during the project/program, in order to acknowledge their concerns and questions. Stakeholders in the keep satisfied-category, such as regulatory bodies, may allow for various voices to be heard, and so the management contractor should ensure that the regulatory requirements are open to interpretation. Furthermore the management contractor should ensure that the suppliers, which may have a portfolio of projects running at any time, are kept satisfied as they may have a great impact on the project, but may have very little interest in the end-result. Finally, the stakeholders in the manage closely-category are the key players, such as financiers, the client, and even the management contractor. They all have strong power and very high interest in the project, and should all be managed closely during the duration of the project/program.

For an in-depth explanation of other methods used for Stakeholder Management, the following article is recommended: Stakeholder Analysis.

Limitations of Stakeholder Management

The process of analysing and mapping stakeholders is usually made prior to or in the beginning of a project, program or portfolio. As a construction project often stretches over a long period of time, it is very likely that some of the stakeholders change attitude during the project, some stakeholders may disappear, or even new stakeholders may occur. For instance, a loud local resident may move away from the construction site, the government might state a new law that affects the construction progress, or the client or the management contractor is bought by a larger company. This limits the functionality of stakeholder mapping, as it should be updated continuously if and when changes happen both internally and externally to the project. Managing stakeholders whose attitudes are changing or whose interest and/or power suddenly shift, can be a challenge that the stakeholder analysis might not have prepared the client for. A solution for these limitations could be to incorporate the possible influences of the stakeholdes within the map. If a stakeholder is often influenced by an external force, then this force should be taken into account by the management contractor as well. This would result in larger and more complex stakeholder maps, with connecting nodes displaying interdependencies and independencies. In other words, by incorporating the potential supply chains or influential network of the stakeholders, it could be possible to predict and act upon sudden changes in the analysis and the stakeholder map. For a more detailed solution of an improved stakeholder mapping method, the following article is recommended: Stakeholders from a dynamic and network perspective.

Managing Stakeholders in Supply Chain Management

A supply chain manager should also manage his stakeholders, although they may differ from the construction stakeholders. Where contracting uses more general methods, such as the power/influence-grid, the supply chain manager often uses a different method. When managing the stakeholders of a Supply Chain, there are often six key principles to be followed. The general methodology of stakeholder management within the supply chain is constant, as the a supply chain is not a single project, but represents a portfolio of projects. This means, that a supply chain may have hundreds of stakeholders to manage at all times.

The six principles (6P) of stakeholder management in a supply chain are:[5]

- 1. Stakeholder Analysis: Exploring the various stakeholders and analyse their interests, strengths, etc..

- 2. Engaging the Stakeholders: Ensuring the stakeholders are willing to change and partake in the project.

- 3. Listening to the Stakeholders: Consider the wishes and concerns of the stakeholders.

- 4. Communicating: Keep the stakeholders aware of the purpose of the project and the current state at all times.

- 5. Using policy positively: Using positive reinforcement (carrot), rather than rules and regulations (stick) to make the stakeholders work.

- 6. Creating Communities: Sharing information and best practices across the organisation.

In SCM, the organisation is often scanned in order to find the various stakeholders both within the organisation and outside the organisations. Such scans are called vertical scans, horisontal scans and external scans[5]. The vertical scan looks up and down the hierarchy of the organisation and the chain, searching for stakeholders at each level. The horisontal scan searches through different departments within the organisation and the chain. The external scan searches for forces from the outside, like government or NGOs that may have an interest in the project. The stakeholder analysis of a supply chain consists of a thorough scan through the organisation and the chain, and afterwards the communication between the different nodes and the client begins. The supply chain relies strongly on the communication and it is expected that a common communication channel is to be used. Often various Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems are used in order to establish a consistent communication channel between the stakeholders and the client.

Limitations of SCM 6P

Unlike general contracting, a supply chain often runs in an infinite time, and thus has no formal end-date. This means, that the supply chain manager must manage all the stakeholders indefinitely. Furthermore, as the supply chain relies strongly on stakeholders and suppliers, the manager must focus strongly on the 5th principle: if a supplier is unsatisfied with his treatment, he may cancel his contract with the client, and the entire supply chain will stop. This means, that the manager must honor the 5th principle, even when facing difficult challenges. As with the general contracting methods, the SCM method must also be updated if/when something changes, and since a supply chain spans over many years changes are likely to occur. The method also brings a strength with it, as the overall communication with the stakeholders, allows for a flowing engaging/listening-method to be applied. As there is already established an ongoing communication agreement with the 4th principle, it is easy for the stakeholders to bring problems and issues to the manager.

Similarities between SCM and Contracting

The SCM method covers many of the same aspects as the general contracting methods. Although these principles may sound very different from the method used in contracting, they are in fact almost the same. As in contracting, the stakeholder analysis is the initial principle of the supply chain stakeholder management. Once the SCM has found the stakeholders through the scan, they are engaged and communicated with, in order to consider their wishes and hopefully push them towards a positive attitude. The ERP system ensures a communication channel, allowing for flowing information sharing in the supply chain. The Winch-Bonke framework allowed the contractor to initially engage and communicate with the stakeholders as well, allowing him to either influence their attitude or compromise between problems and solutions that may have been brought forward.

The two final principles, namely using policy positively and creating communities are the only two principles, that do not necessarily apply to a contracting case, as these are very specific to an organisation and a network. Using the policies of the company to reinforces changes and make the subcontractors deliver on time may be a useful theoretical idea, however such practices are rarely used in contracting cases, as the subcontractors are often external sources from other companies. It is important for a supply chain manager to keep his network satisfied, in order to avoid pauses and buffers within the supply chain. The contractor can deal with unsatisfied contractors by simply replacing them with other subcontractors. Creating a community on the construction site is useful if the contractors are likely to work together in the future, but it is rarely expected nor required from the client, and so the management contractor can ignore this principle.

Conclusion

Analysing and managing stakeholders is crucial for both a construction project/program and a supply chain. By managing the suppliers and resources, and analysing and managing the stakeholders, a manager may have greater insight in the possible outcome of the project, and may even be able to predict reactions in certain scenarios. Although the management of supply chains and subcontractors may seem like two different tasks, they are very much alike. The core difference between a contracting and supply chain management is the life-cycle of the program/project/portfolio. Where the SCM may have a portfolio of continuous projects, constantly undergoing management of stakeholders, the contractor has a program of projects and limited time and finances to manage them. At the end of the contracting project, there is no method that reviews the best practice, as opposed to the SCM portfolio, which constantly shares information and best practices across the organisation.

Notes

21-09-15: Please note that this article will be renamed on the 23rd of September, 2015.

28-09-15: I've tried to change the article's name many times. I've decided to make a new article with the new name and I shall transfer everything to the new page (including the discussion!).

28-09-15: Please note that this article was/is "Contracting as a PM".

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Christopher, Martin. 2011. Logistics & Supply Chain Management, 4th ed. Pearson.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Handbook: For project and construction management - Fundamental concepts by Københavns Erhvervsakademi and VIA University College

- ↑ Guidance on Project Management. International Organization for Standardization.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Winch, Graham M.. 2010. Managing Construction Projects, 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sharma, Raj. 2008. The 6 Principles of Stakeholder Engagement. Reed Business Information.