Managing Projects with Earned Value Management

M vittoria (Talk | contribs) (→Terminology) |

M vittoria (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

===Terminology=== | ===Terminology=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:earned_value_s_curve.jpg| 400px | thumb| |'''Figure X:''' EVM metrics Source: http://www.chambers.com.au/glossary/earned_value_management.php.]] | ||

| + | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ style="caption-side:bottom; "|'''Table X:''' The three main parameters of EVM. | |+ style="caption-side:bottom; "|'''Table X:''' The three main parameters of EVM. | ||

| Line 60: | Line 63: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

==Application of Earned Value Management== | ==Application of Earned Value Management== | ||

Revision as of 21:11, 15 September 2016

However, if any of these dimension is analyzed without taking into account the other two, problems may arise, because only a partial overview of the project status would be provided. For instance, a project may be on budget whilst having accomplished less work than what was planned to be accomplished. On the other hand, a project may also be on budget while having accomplished more work than what was planned. In the first case the project is said to be behind schedule, while in the second case it would be ahead of schedule. How can time measurements be related to costs? And how can managers have an objective overview of the current state of their projects? To answer these questions an effective project control system should be created, to provide managers with timely and accurate information on deviations of costs and time measurements from the objectives established during the planning phase of the project.

This is where Earned Value Management (EVM) come into play by allowing for both schedule and cost analysis against the physical amount of work accomplished. Earned Value Management is a project management technique used for measuring, at any time, the progress and the integrated performance of a project in an objective way. It is an approach that effectively combines the scope of a project with time and costs parameters and allows alerting to deviations from budget and schedule baseline. In this way it can generate early warning signals to detect problems or to exploit new opportunities within the project.

With this methodology it is possible not only to see how a project is performing, but to predict future performance as well. In fact, it is also able to estimate the project completion date and final cost and to provide accurate forecasts of performance problems, which can be a fundamental contribution when managing a project.

Today, Earned Value Management is considered one of the most powerful techniques used in the management of complex projects in commercial, government or private environments. The purpose of this article is to provide the reader with a brief but effective guidance to the concept of EVM and to its application and implementation.

Contents |

Background and purpose

Earned Value Management, formerly known as Earned Value, emerged in its embryonic version in the 1960’s as a financial analysis discipline in US Government programs. It was the creation of an Industrial Engineer, named A. Ernest Fitzgerald, who possessed a wide knowledge of work measurement.

At that time the latest Project Management tool was the Project Evaluation and Review technique (PERT), which was extremely difficult to implement in an efficient manner because of the limited computing technology available at the time [1]. As a consequence, it was not always reliable and timely and therefore not widely used[1] . The computing problems became even bigger[2] when a joint Navy/Stanford team decided to include resources in the PERT by adding Cost information, and introducing the PERT/Cost. Another weakness of the PERT/Cost, in the eyes of Ernest Fitzgerald, was that it adopted updated estimates as the performance measurement baseline. In order to address this and other issues related to performance measurements Fitzgerald founded a consulting firm called Performance Management Corporations (PMC), which delivered, as one of its first products, the highly influential Earned Value Summary Guide, in which a first definition of Earned Value was provided:

“Earned Value is a concept – the concept that an estimated value can be placed on all work to be performed, and once that work is accomplished that same estimated value can be considered to be “earned.” The utility of this concept as a management tool is that the summation of all earned values for work accomplished when compared to what was actually expended to perform the effort can provide management with a comprehensible, objective indicator of how the total effort or any identifiable segment is progressing.”

Shortly afterwards, Earned Value started being introduced and validated in the Ballistic System Division with its implementation in the Air Force’s Minuteman Program. Earned Value won the battle against the PERT/Cost methodology, which was proposed to the Air Force as a valid alternative. The decisive criteria for sticking with Earned Value relies on the inflexibility of its basis for measurements, which, in the case of PERT/Cost could be adjusted to hide overruns, while Earned value used a non-flexible baseline. The PERT/Cost methodology encountered the Air Force rejection and by mid-1966, it was decided that the Minuteman Earned Value approach would be the Air Force standard. Soon Earned Value was expanded to a Department of Defense-wide requirement.

This brief history shows how although performance measurement is the critical structural component of Earned Value, this approach was not created for that purpose only. In fact, in 1965 Estimates at Completion (EAC’s) i.e. the expected costs of a project at the date of its completion, were extremely inaccurate and finding a solution to that problem was the number one objective of Earned Value and the reason why the Air Force and Department of Defense supported it.

Theory of Earned Value Management

The concept

A simple example

DTU is going through an architectural renovation project which involves, among other activities, replacing every outdoor dining table of the campus with new ones. A team has been assigned to this task and the plan is the following:

- 15 batches of 10 tables (150 tables in total) need to be installed

- It is planned to install 3 batches per day (30 tables)

- The budgeted cost per table is 200 dkk. (total budget = 30,000 dkk)

After the first day:

- 25 tables have been installed against the 30 which were planned. (The drill broke down and caused delays).

- The Total Cost for the day was 6,800 dkk. This is because a new drill has been rented and costs 1,800 dkk per day.

Basic EVM calculations for the first day:

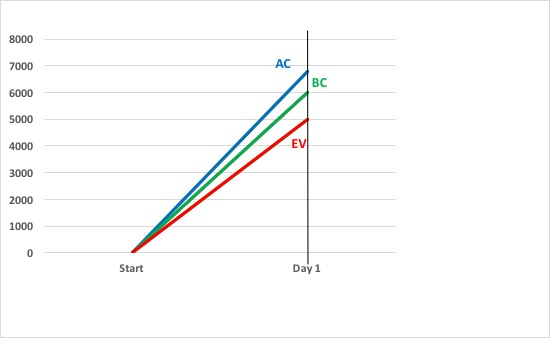

- Earned Value: 25 tables installed * 200 dkk/table installed = 5,000 dkk

- Budgeted Cost: 30 tables planned * 200 dkk/table planned = 6,000 dkk

- Actual cost: 25 tables installed * 200 dkk/table installed + 1,800 dkk for the machine = 6,800 dkk

A visual representation of these 3 parameters is shown in the diagram on the right.

Terminology

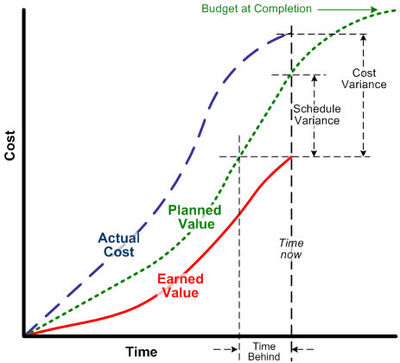

| Planned Value (PV) | Also known as Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS). It is the approved budget for the work scheduled to be completed by a specified date. The total Planned Value of a task is equal to the task’s Budget At Completion (BAC), i.e the total amount budgeted for the task. In the example above it is referred to as "Budgeted Cost". |

|---|---|

| Earned Value (EV) | Also known as the Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP). It is the approved budget for the work actually completed by the specified date. |

| Actual Cost (AC) | Also known as the Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP). It is the costs actually incurred for the work completed by the specified date. |

Application of Earned Value Management

How to implement Earned Value Management

Areas of application

Limitations

See also

Annotated Bibliography

List and short description of the main references used to sustain this wiki article:

- Morin, James B. (2016). How it all began: the creation of Earned Value and the evolution of C/SPCS and C/SCSC. The Measurable News. 15-17. [1]

- A paper that documents the origins of today’s Earned Value Management methodology and describes how and why the Earned Value concept was created in the US back in the 60’s. It provides the reader with a good overview of the context in which Earned Value started being used and it describes how it was developed and accepted as a powerful Project/Program Management tool within the US Air Force’s Minuteman Ballistic Missile system and the Department of Defence.

- EVMS Education Center (2012) Basics concepts of Earned Value Management (EVM). Retrieved from https://www.humphreys-assoc.com/evms/basic-concepts-earned-value-management-evm-ta-a-74-t-1_11.html

- The article represents an introduction to the basics of Earned Value Management, which cover the all the steps from the initial project planning phase until the execution of the plan, going through techniques of data analysis and baseline adjustments. It refers to the Standard for EVMS and addresses the benefit that this methodology can bring to both contractors and customers.