Roadmapping in Program Management

(→Example - How to do it) |

(→Example - How to do it) |

||

| Line 200: | Line 200: | ||

|The team commits to the approach and acknowledges you as the owner of the roadmap, responsible for the process. | |The team commits to the approach and acknowledges you as the owner of the roadmap, responsible for the process. | ||

|[[File:Roadmap_Example_Step_01.png|thumb|200px|]] | |[[File:Roadmap_Example_Step_01.png|thumb|200px|]] | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

|02 | |02 | ||

Revision as of 13:56, 26 September 2016

Contents |

Overview

A roadmap is a time-based chart that aligns multiple planning layers (such as marketing-, product-, development-plan) with strategic business objectives. Its main idea is to create one integrated planning approach. This way, strategic pathways towards specific trajectories can be found, compared and decided while taking into account the planning elements’ interdependencies, mutual requirements and synergies.[1] Due to this holistic approach, technology roadmaps are a valuable tool for program management in organisations in two ways:

- To analyse and define the need for initiatives and/or programs as well as their design;

- To administer programs and their underlying activities.

In this article, the main focus will be on how to use technology roadmaps for the definition of (organizational) programs. For that, the key aspects of roadmaps and their purposes are described. Afterwards, the utilisation and the benefits of roadmapping for program management are discussed. As a third step, a roadmapping toolbox as well as an example for practical use are presented. Finally, the limitations of roadmapping processes are discussed emphasizing the necessity of a continuous and integrated roadmapping system.

Understanding Technology Roadmaps

Technology Roadmaps were first broadly introduced in the 1970s when pioneers like Motorola used them to integrate their technology and product development/planning. Since then, several types of roadmaps have been developed for different purposes (e.g. Service/Capability Roadmap for service-driven companies or knowledge asset roadmap for knowledge-driven companies). What they have in common is the approach of extrapolating or ‘’forecasting’’ effects of certain elements into the future and/or backcasting future goals/expected trends into current activities.[2] In order to visualise these aspects, most roadmaps share certain commonalities described below.

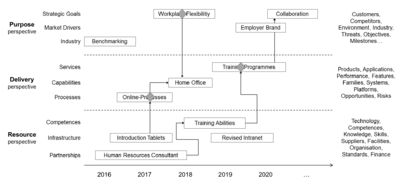

Key Aspects - What they look like

Roadmaps are time-based charts that depict projects, initiatives, technologies and other planning objects on several layers. The timeframe (x-axis) typically spans several years and may include the past as well for reference. Even though specific dates will increase the roadmap's explanatory power, relatively vague estimates (such as "now", "plans", "strategy") may be useful in some cases.

The y-axis depicts the different planning layers in which the projects and activities can be categorized. These can mostly be joined into three main perspectives (blocks):

- Resource perspective (bottom-layers): e.g. technologies, resources

- Delivery perspective (middle-layers): e.g. products, services, systems

- Purpose perspective (top-layers): strategic objectives, markets, business

A more detailed overview including possible layer-categories can be found in figure 01.

Within this framework, bars, and milestones are arranged to represent the activities and initiatives. The interrelations are represented by arrows that connect the different elements often times spanning several layers.

However, timeframe, layers as well as the type of activities etc. often are (and should be) subject to customization according to the specific case. The most important aspect for this customization is the purpose of the roadmap that may differ broadly. Also, next to the most common visualization presented above, there are other methods, e.g. tables,graphs,flow charts and others, that may be better suited to represent the situation comprehensively in some cases. [3]

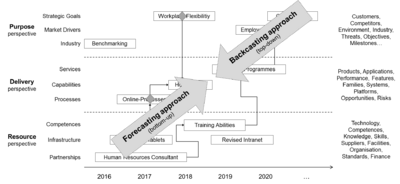

Reading Direction - How to interpret them

Typically roadmaps can be understood following a diagonal from the bottom-left to the top-right corner (as indicated in figure 02). Depending on the direction along this line, one obtains either an

- backcasting-approach (top-right to bottom-left corner) following the market/objective pull, or

- forecasting-approach (bottom-left to top-right corner) following the technology/resources push.

Following the top-down direction, the market/objective pull is first represented by the strategic business goal that propagates through the product portfolio plan, and finally the technologies and resources to be developed (backcasting). Thus a holistic approach to fulfilling market or strategy needs can be tracked. The other way around (bottom up), one may estimate the effects of a new technology or resource and how it can affect future products and therefore shape markets (forecasting). In practise, both directions are often merged as there will always be some idea about future developments as well as strategic implications.

Technology Roadmapping in Program Management

According to the PMI-Standard, Program management is the centralized coordinated management of a program to achieve the program's strategic benefits and objectives with a program itself being a group of related projects managed in a coordinated way [...].[4] Comparing these definitions to the overall idea of technology roadmaps - namely the coordination of multiple elements on several layers, to support specific (business) objectives and/or to analyse effect of certain elements on those goals - it becomes clear, that roadmaps are a highly applicable tool for program management. Considering the different program performance domains, roadmaps can play out their strengths in program-strategy-alignment, as well as in benefit-orientation and holistic program design. That being said, they may also be used in the same way for projects (on a smaller scale) as well as to ensure fit within portfolios of projects and programs. To realize these benefits, roadmaps should be defined when initiating a program and constantly revised over the course of it, to manage the design as well as the execution. Therefore, especially in the program management context, roadmaps are to be seen as dynamic documents.[5]

|

Note: Roadmaps in the PMI Standard: |

Benefits - What they can do

The key benefit of roadmaps in program management is coordination and alignment. Their high-level scope and their focus on interdependencies enable an organisation to guarantee fit between the programs' elements.[4] Especially the process of roadmapping helps asking the right questions to design holistic programs that do not lack critical projects/activities. However, roadmaps improve program management in even more ways:

- Improve commitment and understanding, as they communicate a high-level overall scope and execution of the program;

- Help avoid costly mistakes, as they reveal gaps in the overall program;

- Provide direction and focus, as they link program elements to overall strategic objectives;

- Improve stakeholder/resource management, as they point out key contributors for program success and/or unveil hidden resources

- Help save unnecessary cost/guarantee return on investment, as they focus on benefit/value creation (therefore contribute to lean program management);

- Contribute to risk management efforts, as ripple-effects are easier to foresee;

- Improve collaboration, as they summarize key deliverables/interfaces;

- Improve decision making, as consequences are easier to foresee;

- Clarify responsibilities, as they define clear tasks/milestones.

Methodology - How to use it

Roadmaps can be used to design a program from scratch, review and/or improve it. In the following the focus will be on the definition from scratch, as it includes all other steps. If the program is to be reviewed or improved, one can simply start at one of the latter process steps. Following the forecasting/backcasting approach, a program roadmap is guided by the following questions, inputs etc.:

| Key Question |

|

| Key Input |

|

| Key Activity |

|

| Key Output (note the similarity between fore- and backcasting approach) |

|

Application - How to adjust

Consequently, according to the different types of programs, namely Engineering Programs, Organizational Change Programs and Societal Programs Technology Roadmaps may be used as follows:

- Engineering Programs

- In engineering programs, technology roadmaps can be used to analyse the effects of emerging technologies on the industry/organisation, or (the other way around) to see which technologies need development to realise a strategic product portfolio or the like. For example:

- Forecasting: Phone manufacturers might analyse the probable impact of flexible displays in order to assess the need for programs to pursue this trend. They may also plan generation-spanning rollout-plans and there product (platform) development programs.

- Backcasting: Car manufacturers might examine which resources to acquire, capabilities and technologies to develop etc. to position them as a leading e-car-brand in the future.

- Organizational Change Programs

- In change programs, (next to IT and supporting technologies), methodologies and knowledge takes the place of "technology". It may therefore be used to assess if the current pathway complies with the company's vision of the future (and to define the corresponding program's elements to get back on track). Next to that, a strategic organizational change may be translated into the required projects (and therefore a program). Examples might be:

- Forecasting: Companies may validate the impact of social networks for their internal structure and design a program that promotes, mitigates or direct the effects.

- Backcasting: Organizations may design programs that involve human resource strategies, IT-systems, new processes as well as training and education etc. to facilitate a learning organization.

- Societal Programs

- On a societal level, possibilities for roadmaps are broad and depend largely on the perspective of the roadmap owner. Mostly, they face the question of how society will develop according to major trends or how "big issues" may be solved. For example:

- Forecasting: Governments may use the approach to assess the impact of smoking on an aging society (including social systems, health care etc. as layers).

- Backcasting: NGOs may develop roadmaps on which initiatives, farming methods and technologies may mitigate world hunger.

Guideline for facilitation

Numerous process descriptions of how to carry out roadmapping exist (e.g. T-Plan-process[7], Integrated Roadmap process [8], Program roadmap process [9]). They differ vastly due to the different purposes and types of roadmaps, however they all point out three main aspects that are essential to any roadmap:

| Step | Key Question | Means | |

| 01 | Planning |

|

Discussion with core team, approval meeting with board, input gathering from project and line managers. |

| 02 | Definition of current and future state |

|

Analysis in core teams, strategic decision from strategic planning and organizational goals (board). |

| 03 | Gap Analysis |

|

Workshops (often per layer) with respective departments, experts as well as outside consultants. |

| 04 | Implementation |

|

Using existing processes, facilitating hierarchical power of roadmap owner, gathering a “board of project managers” and the like. |

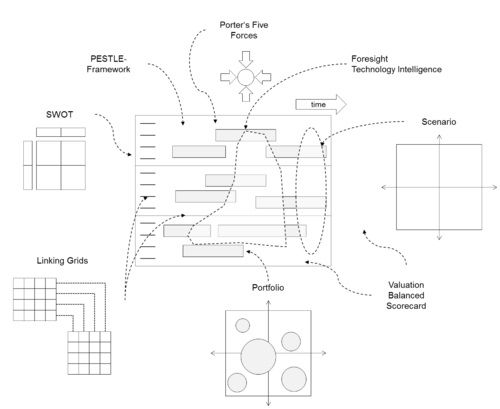

However, since roadmapping is such a highly customizable undertaking, it is barely possible to define a more precise universal approach. That does not mean though, that there is no need for a structured process. On the contrary, especially the quality of information and the combination of it is essential to a successful roadmap. Due to that, a roadmapping toolbox is presented containing models and processes that help facilitate the building process of a roadmap. Its focus is on the utilization of information that should mostly be available in an organization anyways.

Toolbox - Support the process

If the necessary information is not at hand from the beginning, the following toolbox offers an array of supporting measures (see figure 03). It is explained briefly how/for what to use the method in the context of roadmapping. They are organised so they comply with the order of most roadmapping processes. (Click the models names for respective links.)

- Market and technology assessment should be utilised to estimate the scope and "clockspeed" of development. Depending on that, the timeframe for the roadmap should be chosen. (Step 1 and 2)

- SWOT-Analysis can be used to choose the right focus areas for the companies program (layers of the roadmap) as well as to indicate gaps within/between the layers. (Step 1 and 2)

- Portfolio-Analysis is useful to define the overall scope as well as to organize the options within the different layers (e.g. technology resources at hand). (Step 2)

- PESTLE-framework the factors political, economic, social, technological and environmental trends and drivers can be used to assess the top layers of the roadmap to find out key trends. (Step 2)

- Porter's Five Forces may be used if the competitive environment is highly relevant, e.g. when the roadmap is used to design strategic differentiation programs. (Step 2)

- Delphi-method should be used to gather inside and outside expert's opinions on the initiatives and developments. (Step 3)

- Valuation techniques such as net-present value, discounted cash flow, balanced scorecard or the like should be used to assess the different options (projects, technologies, etc.). (Step 3 and 4)

- Linking grids similar to Quality Function Deployment these grids link and translate higher-level aspects into lower-level requirements. Thus, they are crucial when linking the roadmaps layers. (See [7] for further explanation.) (Step 3)

- Scenario Techniques should be used to create different pathways and to assess possible future developments. (Step 4)

Example - How to do it

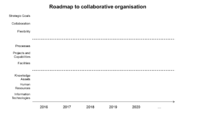

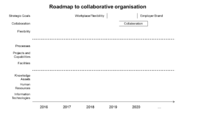

| Example: You are program manager tasked by the CEO to put a program into place, that changes the company to become a truly collaborative work environment to be ready for future competition. They expect a well-rounded solution including the whole company. |

| Step | Action | Result | ||

| 01 | Team Set up | You set up a team including all major stakeholders in the company to discuss the matter and get everyone on board. | The team commits to the approach and acknowledges you as the owner of the roadmap, responsible for the process. | |

| 02 | Clarify the purpose | You meat with the board to discuss the overall goal. | The purpose of the roadmap is defined as "Define a roadmap which resources, technologies and capabilities to acquire/develop to become a collaborative business within 5 years". | | |

| 03 | Choose basic dimensions | You meet with the core team and discuss the basic layout of the roadmap according to current market and technology information. | x-Axis: The 5-year-timeframe required is acknowledged as realistic. The following layers are decided to have an impact: y-Axis: |

|

| 04 | SWOT-Analysis | To analyse the current capabilities you screen the company strengths and weaknesses in relation to the opportunities and threats of not pursuing the collaborative approach. | You realize that next to collaboration, flexibility and maintaining visibility are key capabilities. | |

| 05 | Portfolio-Analysis | Together with the responsible colleagues (process managers, facility managers etc.) you analyse process maps, facilities at hand and knowledge assets. You decide which contribute to the key capabilities, and which you would need. | You now can fill in the as-is-state and already have first ideas for a to-be-state. | |

| 06 | PESTLE-Analysis | With the core-team you analyse outside trends and factors that might have an impact on the overall goal. | You find that the goal seems valid, from a HR-standpoint you realize, that employee expectations will change over the course of the program. | |

| 07 | Gap Analysis / Delphi-Method | You carry out several workshops (at least one for each layer) with experts from the company on which measures to take to fill the gaps. | Afterwards you have an array of possible projects for the program and how they would contribute to the benefit creation. | |

| 08 | Valuation | You meet with cost experts and controlling to estimate project costs and benefits. | The project/initiative array is now prioritized. | |

| 09 | Linking Grids | According to the prioritisation, you now use linking grids to connect the initiatives to each other and the overall goal. | For example: Collaboration needs flexible workspaces (adjusting facilities), which require cloud-based solutions and processes (redesign processes), which require wireless IT-solutions (invest in notebooks and wireless access points). | |

| 10 | Scenario-Analysis | Together with experts you create different scenarios to prove the programs robustness and schedule accordingly. | You can now present a validated, cost-estimated, logically connected holistic program that offers the required benefit. | |

| 11 | Action Plan | You can now distribute the projects including the most relevant interfaces and milestones. | Continuous feedback from project controlling | |

| 12 | Continuous Process | Constant revising of the roadmap according to project feedback and market/industry intelligence. | Revisions of the roadmap |

Discussion

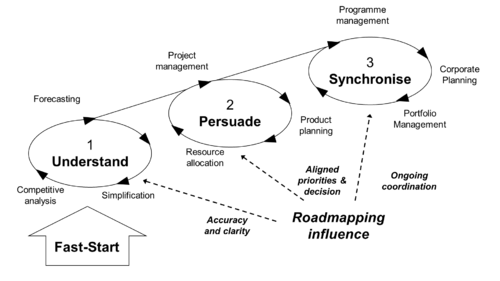

As shown, technology roadmaps are very useful when applied even for only one specific case/question. However, they can unfold their full potential only if they are part of a continuous process that is deeply embedded in the strategic PPM planning process (see figure 05). It should make use of all information available to truly integrate across all areas of an organisation. However, implementing and maintaining such a process takes time and until now, only very few companies manage to integrate them in that fashion. Organisations should therefore be aware of the fact, that if they decide for roadmapping as part of their strategic planning, they should be in for the long run. Only after learning how to use roadmaps to understand matters and how to make them persuasive for others, they can truly be used to synchronise programs, strategy and planning. [10] Due to these impediments, roadmaps are especially interesting for bigger companies, where interrelations or connections are not clearly visible and the necessary pre-requisites exist.

Next to this overarching restriction, there are some critical aspects to roadmaps, that determine their success or failure within an organisation and should be kept in mind.[5]

- Accuracy and actuality of information

Although technology roadmaps are a powerful tool to visualize organisation-spanning programs, they are just as good as the underlying data and information. Especially the probabilistic nature of the assumptions about the long-term development thus calls for steady refinement and evaluation. Check and update information as time unfolds.

- Shortcutting the process

Organisations should not be misled by the simplistic appearance of a roadmap. As shown, a lot of effort is needed to design a program roadmap - including lots of lengthy discussions about opinions and best practices. However, this exact process is what creates the value of the roadmap, as it unveils the logical links between the mass of information. Thus: Understand the roadmap as the result of an even more important roadmapping exercise.

- Link to decision-making and operations

Roadmaps will stay visualisations if there is no proper link to strategic and decision-making. This is why the process described emphasizes the action plan. Ways to link are the hierarchical position of the roadmap owner, the purpose definition, and the like. Therefore: Ensure to translate understanding into implications and customize the process to needs.

Recommended Literature

Phaal, Robert et al. (2005): Developing a Technology Roadmapping System; University of Cambridge

In this compact article, Robert Phaal focuses on the customization of roadmaps. After introducing the roadmapping methodology briefly, the focus is on the integration of roadmapping in an organisation’s strategic planning process. It is elaborated how to make roadmaps work in organisations and the need for development (maturity model) of a roadmapping system is pointed out. Phaal's key point is that the organization should tailor the roadmapping process according to its needs and capabilities.

Milosevic, Dragan et al. (2007): Program Management for Improved Business Results; John Wiley & Sons Inc. (Chapter 10)

This book represents a very structured overview of all facets of program management.

In chapter 10 specifically, Milosevic presents a very short and to-the-point description of the benefits and elements of a roadmap. The most interesting part however is the relation to other strategic planning methods (such as portfolio management and the like).

Behrendt, Siegfried (editor) (2007): Integrated Technology Roadmapping: A practical guide to the search for technological answers to social challenges and trends; Zentralverband Elektrotechnik und Elektroindustrie e.V.

“Integrated Technology Roadmapping” emphasizes the realisation of roadmapping in the context of societal programs. It presents a process model tailored for programs targeting societies “big questions” and considers key practical tips (such as risk management, uncertainty, and stakeholders).

Moehrle, Martin et al. (editors) (2012): Technology Roadmapping for Strategy and Innovation: Charting the route to success; Springer.

Moehrle et al. focus on roadmapping to link (technological) innovation and strategy. This book is thus especially interesting for technology-driven businesses as it presents a very detailed scope concerning background, process, implementation of technology roadmapping and the link to strategic planning.

Bernal, Luis et al. (2009): Technology Roadmapping Handbook; University of Leipzig.

This short handbook provides a very good overview of the different types of roadmaps and their elements. It does not go in-depth but gives an initial idea about the alternatives that should suffice to specifiy one’s needs.

References

- ↑ Moehrle, Martin et al. (editors) (2012): Technology Roadmapping for Strategy and Innovation: Charting the route to success; Springer.

- ↑ Bernal, Luis et al. (2009): Technology Roadmapping Handbook; University of Leipzig.

- ↑ Phaal, Robert et al. (2004): Customizing Roadmapping; in: Research Technology Management Vol. 47.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Project Management Institute (2006): The Standard for Program Management; 2nd edition.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Milosevic, Dragan et al. (2007): Program Management for Improved Business Results; John Wiley & Sons Inc..

- ↑ Project Management Institute (2013): The Standard for Program Management; 3rd edition.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Phaal, Robert et al. (2001): Technology Roadmapping: linking technology resources to business objectives; University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Behrendt, Siegfried (editor) (2007): Integrated Technology Roadmapping: A practical guide to the search for technological answers to social challenges and trends; Zentralverband Elektrotechnik und Elektroindustrie e.V..

- ↑ Byrne, Kevin et al. (2013): How to Prepare a Program Roadmap; Journal of Evonomic Development, Management, IT, Finance and Marketing, Issue 6.

- ↑ Phaal, Robert et al. (2005): Developing a Technology Roadmapping System; University of Cambridge. Link