Knowledge management in projects and organizations

Aitor.altuna (Talk | contribs) (→Discussion) |

Aitor.altuna (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

== Barriers to effective knowledge management == | == Barriers to effective knowledge management == | ||

| − | Knowledge management, if done effectively, can be very helpful and useful for an organization. However, there are some barriers that prevent organizations establish these practices. Most of the barriers to effective knowledge management involve people. Human beings are complex with diverse psychological needs. Data and documents need to be stored somewhere. | + | Knowledge management, if done effectively, can be very helpful and useful for an organization. However, there are some barriers that prevent organizations establish these practices. Most of the barriers to effective knowledge management involve people. Human beings are complex with diverse psychological needs. Data and documents need to be stored somewhere.<ref name=Audrey<i>Audrey S. Bollinger, Robert D. Smith (2001). "Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset", ''Journal of Knowledge Management''. Retrieved 11.09.2016. [http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/13673270110384365 Available Online] </ref> |

| − | From organizational perspective, the process of building these knowledge bases can be very time consuming, labour intensive and costly. People are already busy, and sharing knowledge may mean changing how they work or adding extra steps to the process to extract the data and enter it into a database. There have been significant limitations to the achievement of effective knowledge processing and knowledge-based systems up to date. Tools of knowledge engineering are being adapted for use in knowledge management but the technology is not yet sophisticated enough for large-scale application. It can be difficult to keep track of discussions and decisions when teams work on temporary projects. It is difficult to codify tacit knowledge. In addition, knowledge is constantly changing both at the individual and organizational levels. The gap between what people actually do to perform their jobs and how it is documented is difficult to bridge due to spontaneous actions people take in response to unexpected challenges and problems. | + | From organizational perspective, the process of building these knowledge bases can be very time consuming, labour intensive and costly. People are already busy, and sharing knowledge may mean changing how they work or adding extra steps to the process to extract the data and enter it into a database. There have been significant limitations to the achievement of effective knowledge processing and knowledge-based systems up to date. Tools of knowledge engineering are being adapted for use in knowledge management but the technology is not yet sophisticated enough for large-scale application. It can be difficult to keep track of discussions and decisions when teams work on temporary projects. It is difficult to codify tacit knowledge. In addition, knowledge is constantly changing both at the individual and organizational levels. The gap between what people actually do to perform their jobs and how it is documented is difficult to bridge due to spontaneous actions people take in response to unexpected challenges and problems.<ref name=Audrey<i>Audrey S. Bollinger, Robert D. Smith (2001). "Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset", ''Journal of Knowledge Management''. Retrieved 11.09.2016. [http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/13673270110384365 Available Online] </ref> |

| − | At the individual level, people are often reluctant to share information if they fear criticism from their peers or recrimination from management. This can occur if there is lack of respect, trust and common goals among the different people within the company. Professional knowledge is perceived as a source of power. There is a sense of worth and status to be gained because of expertise. People tend to have feelings of “ownership”. There can also be fear that there will be a diminished personal value after giving up know-how. Competition among professionals can be intense and, as a result, knowledge can be lost. | + | At the individual level, people are often reluctant to share information if they fear criticism from their peers or recrimination from management. This can occur if there is lack of respect, trust and common goals among the different people within the company. Professional knowledge is perceived as a source of power. There is a sense of worth and status to be gained because of expertise. People tend to have feelings of “ownership”. There can also be fear that there will be a diminished personal value after giving up know-how. Competition among professionals can be intense and, as a result, knowledge can be lost.<ref name=Audrey<i>Audrey S. Bollinger, Robert D. Smith (2001). "Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset", ''Journal of Knowledge Management''. Retrieved 11.09.2016. [http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/13673270110384365 Available Online] </ref> |

| − | To conclude, organizational culture plays a primary role in the likelihood that employees will be willing to work together and share their knowledge. If the culture is not supportive, or the reward system favours only individual effort, it may be difficult to get people to work together. Some organizations use a chief knowledge officer (CKO) to coordinate the knowledge management. This implies controlling people, and if that is the employees’ perception, it will be destined to fail. High levels of motivation, creativity and adaptability are required for the “care-why” level of knowledge to exist. This in turn is dependent on the culture of the organization. People will not use the technology if there is a lack of trust, respect and interest in common goals. | + | To conclude, organizational culture plays a primary role in the likelihood that employees will be willing to work together and share their knowledge. If the culture is not supportive, or the reward system favours only individual effort, it may be difficult to get people to work together. Some organizations use a chief knowledge officer (CKO) to coordinate the knowledge management. This implies controlling people, and if that is the employees’ perception, it will be destined to fail. High levels of motivation, creativity and adaptability are required for the “care-why” level of knowledge to exist. This in turn is dependent on the culture of the organization. People will not use the technology if there is a lack of trust, respect and interest in common goals.<ref name=Audrey<i>Audrey S. Bollinger, Robert D. Smith (2001). "Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset", ''Journal of Knowledge Management''. Retrieved 11.09.2016. [http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/13673270110384365 Available Online] </ref> |

== Annotated bibliography == | == Annotated bibliography == | ||

Revision as of 21:26, 26 September 2016

Knowledge management (KM) is the process of capturing, developing, sharing, and effectively using organizational knowledge. [1] The aim of this article is to identify within a project in an organization how knowledge is created, transferred and reused in a project management environment. Two main areas will be studied: intra-project and inter-project learning and organizational memory and knowledge sharing.

Intra-project learning consists of knowledge created and shared within a project, whereas inter-project learning is based in reusing existing knowledge from project to project. There are mainly two types of knowledge: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is knowledge that is expressed tangibly and can potentially be stored in databases or documents. Tacit knowledge, instead, is stored in a person´s head and cannot be readily expressed in words. Managing both of them correctly within an organization is essential for effective knowledge management.[2]

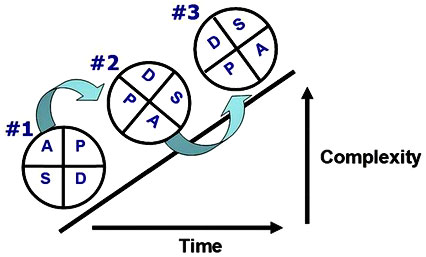

Intra and inter-project learning is explained through the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. The PDSA cycle is based on the premise that for an organization to continually improve or learn they need to plan for it, implement the plan, analyse or study the results and act on the analysis. Intra-project learning is the process in which new knowledge is created when overcoming problems in projects. Intra-project learning can occur in different ways but should be documented in order to transfer it to other projects within the company. This concept is called knowledge reuse.[2]

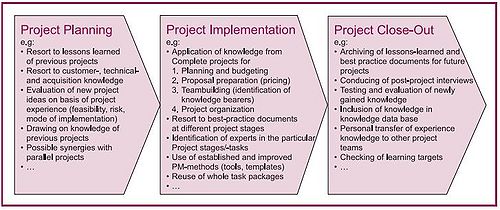

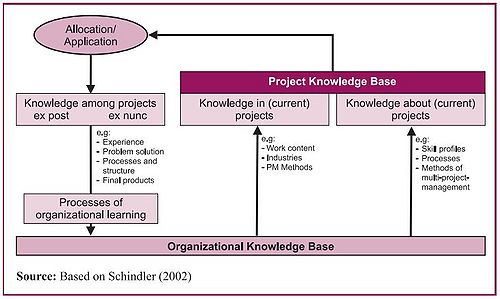

Knowledge that is gained in different projects needs to be transferred to an organization's memory for reuse on other projects. This information transfer is essential for the organization's prosperity. Therefore, a knowledge management strategy should developed to determine how knowledge should be reported, stored, shared and used.[3]

Contents |

Importance of knowledge management

Knowledge is a vital resource in project-based industries such as aerospace, construction, shipbuilding and software. Considering management of knowledge is a necessary prerequisite for project success in today’s dynamic and changing environment. [4]

Key business objectives for project management in companies are to: increase customer retention and acquisition, increase returns on projects, and minimize risks. Crucial factors in achieving these objectives are related to managing, applying and reusing knowledge gained throughout the project life cycle. If useful information is identified, assimilated and retained within the organization, it represents intellectual capital that can be reused on other projects, reducing the time staff spend recreating what has already been learned, and therefore improving project management in general. Such organizations must continually develop their core competencies or project management capabilities to successfully win and execute projects to meet client needs.[2]

Effective project management is a key enabler for business success. However, where corporate knowledge is ineffectively managed during the project lifecycle, valuable intellectual capital is lost or devalued, causing rework and lost opportunities. The management and transfer of knowledge can support an organization in improving organizational learning. From the project management point of view, this in turn should help deliver more projects on time and within budget, or alternatively deliver projects of a higher quality for an increased profit. This also leads to higher customer satisfaction and better reputation for the organization.[2]

To succeed competitively and to achieve their business strategies and goals, organizations such as project management organizations need an effective knowledge management strategy in order to maintain valuable intellectual capital and not causing rework to employees. Effective knowledge management and learning are also essential to ensure a qualified and polyvalent staff. It also affects to the personal satisfaction of employees, as they consider their work to be valuable and efficient. For technology-based organizations, continuous learning is a helpful strategy to remain innovative.[2]

Intra and inter project learning and knowledge creation

In a company, two projects will never be exactly the same. Possibilities to find similar projects are high, but each project is unique due to several factors such as project definition, tasks or members, among others. Therefore, projects are especially suitable for learning. [5]

PDSA cycle

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle is an iterative, four-stage problem-solving model used for improving a process or carrying out change. It is also known as the PDCA cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act) or the Deming wheel. Applied to the field of knowledge management, it is used to characterize knowledge creation and learning in a project management environment, and is linked to the Project Management Institute´s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK). The PDSA model is valid to explain two possible situations in a project-based environment. On the one hand, it can explain the process within a project where an iterative process is used to find the best solution for a problem. This means that inside a project there are several PDSA cycles, and the design is improved and refined until the final solution is obtained. On the other hand, taking into account that a project is a single PDSA cycle, it explains how knowledge that is gained from one project can be saved and transferred to be reused in future projects.[2][7]

In both cases, The PDSA cycle is based on the premise that for an organization to continually improve or learn they need to plan for it, implement the plan, analyze or study the results and act on the analysis [2]. In the following explanation the second situation will be considered, but it can be perfectly applicable to the first situation as well.

The “Plan” step is where the cycle usually starts. When a project is assigned to a project manager, the first step is to plan and decide how it is going to be carried out. There are several points that need to be taken into account. The most relevant ones are explained next:[7]

• Recruit a team: Assemble a team that has knowledge of the problem or opportunity for improvement. Consider the strengths each team member brings and look for a balanced, engaged and forward-thinking staff. Roles and responsibilities should also be identified and assigned to all the members of the group.

• Describe the problem: It is important that all the members of the group have a clear understanding of the problem.

• Define the goal: The objectives of the project need to be clear and every member of the group should know what needs to be accomplished.

• Make a plan: Analyze how the previously defined goals could be accomplished in the most efficient way. Develop an action plan, including necessary resources and a timeline. Identify risks that might come up in the implementation process and develop alternatives in relation to the risks.

The "Do" step is where the project team implements the previously defined plan. During this process the project team identifies problems that were not planned in the previous stage and these need to be solved in order to deliver the project successfully. Learning takes place when project team members discuss approaches for completing a task or overcoming problems. Knowledge is created by individuals and groups building on existing knowledge and creating new knowledge. This knowledge can either be coded in project documentation or is stored with the project member, as it usually occurs in informal situations. The intra-learning occurs continually throughout the project life cycle. A way of ensuring that project learning occurs is to ensure that knowledge is captured at regular review points during the project lifecycle.[2][8]

In the "Study" step the project team reflects on the associated plans, and assesses what has occurred in the project, determining both good and bad instances. The output of this step is a lesson learned, which is a tool to consolidate the knowledge gained throughout the project. A lesson learned overcomes the barriers to organizational learning and knowledge sharing by playing two roles. First, the process of developing a lesson learned provides an opportunity for the project team to take reflective time to gain a full understanding of project results. Actions are identified as good or bad as well as procedures to carry them out. The lesson learned should describe the actions to take or avoid on similar projects. Second, a lesson learned is a mechanism to document the learning of the project team to share with other members in the company [8]

The "Act" step is the next step where the cycle is completed and knowledge gained from one project can be input into future projects. It represents the transition from project to project. Then, if a project as a whole is seen as a PDSA cycle, the "Act" step is the one that links one cycle with the next one. For example, a lessons learned document of a current project supports the planning stage of the next project by providing information and knowledge gained from one PDSA cycle to another.[2]

An example will be shown next. Boeing first introduced the 737 and 747 plane programs with serious problems. To ensure that problems were not repeated, senior managers commissioned a high-level employee group, called Project Homework, to compare the development processes of the 737 and 747 with those of the 707 and 727, two of the company's most profitable planes. The group was asked to develop a set of "lessons learned" that could be used on future projects. After working for three years, they produced hundreds of recommendations and an inch-thich booklet. Several members of the team were then transferred to the 757 and 767 start-ups and guided by experience, they produced the most successful, error-free launches in Boeing's history.[10]

This is a example that shows perfectly all the steps of the PDSA cycle. The critical step in this cycle was definitely the "study" part, as they gave a high relevance to observe and analyze the differences between the planes that failed and the ones that succeed. It also shows how explicit and tacit knowledge were managed. Explicit knowledge was created by noting down recommendations in a booklet, whereas tacit knowledge was also transferred as these individuals were part of the new project team.

Organizational memory and knowledge sharing

Knowledge that is gained in a project needs to be transferred to an organization´s memory for reuse on other projects. Organizational memory is the accumulated body of information and knowledge created in the course of an individual organization´s existence.[2] The organizational memory can be divided up in two main groups: organization´s archives (including its electronic data bases); and individual´s memories.[3]

The challenge is to capture and index this knowledge for retrieval while it is available, as project teams are temporary. The context in which knowledge transfer happens is important, especially for tacit knowledge, because usually people exchange knowledge personally based on trust and experience. As stated in the previous chapter, a project knowledge base is created when a project is carried out. This knowledge is stored in two ways mainly: formal and explicit documentation (lessons learned) and within each of the individual members of the project group. This information will not be useful for the organization unless it is shared with other members in the organization. It is essential that this information is shared effectively. For that purpose, a knowledge management plan should be established. If done it successfully, the loss of information throughout the process would be minimal, enhancing the reuse of knowledge for other projects.[2][3]

Explicit knowledge is usually shared through archives or documentation. Lessons learned from all the different projects that the organization has carried out throughout years should be archived and stored for future look up by any of the members of the organization. Bear in mind that employees will also use it as a source of learning if the system is easy and straightforward. Therefore, knowledge management tools are a great step forward in order to keep the information well-structured and organized. Computer-based information systems have been key in the improvement of such databases, which make the information exchange much easier and convenient. In this way, the information remains stored within the organization and it is ready for lookup and reuse in future projects. [11]

Tacit knowledge is the knowledge that is in a person´s head that is often difficult to describe and transfer. It includes lessons learned, know-how, judgment and intuition. there are so many nuances involved that it can be difficult, if not impossible, for individuals to describe what it is that they know.[3]

Absorbing facts by reading them or seeing them demonstrated is one thing; experiencing them personally is quite another. It is very difficult to become knowledgeable in a passive way. Actively experiencing something is considerably more valuable than having it described. This type of knowledge is usually shared within the members of the organization based on trust and experience; therefore, human relations and social behavior play a key role. Some practical means of transferring tacit knowledge will be explained shortly next:[10]

• Tours within the organization: it allows employees to see how other colleagues work and knowledge is shared.

• Personnel rotation programs: probably one of the most powerful methods of transferring knowledge. Those in daily contact with these experts benefit enormously from their skills. Transferring them to different parts of the organization helps share the wealth and knowledge.

• Training programs within the company: this enables social networking and enables knowledge sharing among its members if they are well designed.

Continuous learning is essential for companies in fast-growing industries to be able to respond to changes in the business environment. In order to maintain competitive advantage, organizations need to learn and obtain knowledge faster than their competitors. A knowledge management strategy is developed by the organization for improving how it develops, stores and uses its corporate knowledge. Both tacit and explicit knowledge are important in the creation and reuse of knowledge. Organizational memory forms the basis of intellectual capital that is held in an organization. Intellectual capital is the knowledge and capability to develop that knowledge in an organization.[2][10]

Four key factors are critical to a project-based organization´s capacity to learn:[2]

• A culture that encourages learning

• A strategy that allows learning

• An organizational structure that promotes innovative development

• The environment

These factors contribute to individuals creating, transferring and reusing knowledge leading to organizational learning. For a project organization to continually learn and develop, organizational learning needs to occur. Organizations with these characteristics and mindset, that integrate learning as part of their business, are called learning organizations.[2]

Barriers to effective knowledge management

Knowledge management, if done effectively, can be very helpful and useful for an organization. However, there are some barriers that prevent organizations establish these practices. Most of the barriers to effective knowledge management involve people. Human beings are complex with diverse psychological needs. Data and documents need to be stored somewhere.[3]

From organizational perspective, the process of building these knowledge bases can be very time consuming, labour intensive and costly. People are already busy, and sharing knowledge may mean changing how they work or adding extra steps to the process to extract the data and enter it into a database. There have been significant limitations to the achievement of effective knowledge processing and knowledge-based systems up to date. Tools of knowledge engineering are being adapted for use in knowledge management but the technology is not yet sophisticated enough for large-scale application. It can be difficult to keep track of discussions and decisions when teams work on temporary projects. It is difficult to codify tacit knowledge. In addition, knowledge is constantly changing both at the individual and organizational levels. The gap between what people actually do to perform their jobs and how it is documented is difficult to bridge due to spontaneous actions people take in response to unexpected challenges and problems.[3]

At the individual level, people are often reluctant to share information if they fear criticism from their peers or recrimination from management. This can occur if there is lack of respect, trust and common goals among the different people within the company. Professional knowledge is perceived as a source of power. There is a sense of worth and status to be gained because of expertise. People tend to have feelings of “ownership”. There can also be fear that there will be a diminished personal value after giving up know-how. Competition among professionals can be intense and, as a result, knowledge can be lost.[3]

To conclude, organizational culture plays a primary role in the likelihood that employees will be willing to work together and share their knowledge. If the culture is not supportive, or the reward system favours only individual effort, it may be difficult to get people to work together. Some organizations use a chief knowledge officer (CKO) to coordinate the knowledge management. This implies controlling people, and if that is the employees’ perception, it will be destined to fail. High levels of motivation, creativity and adaptability are required for the “care-why” level of knowledge to exist. This in turn is dependent on the culture of the organization. People will not use the technology if there is a lack of trust, respect and interest in common goals.[3]

Annotated bibliography

1. Peter Senge, "The fifth discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization", Currency Books (Revised Edition) 2006. ISBN 0-385-51725-4.

The book Fifth Discipline is Peter Senge's account of the learning organization. For Senge, five disciplines are necessary to bring about a learning Organization—personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, team learning, and systems thinking. Systems thinking is the discipline that integrates all five disciplines. Each discipline is briefly explored with emphasis placed on systems thinking. Senge's concern with localness and openness is also touched upon.

2. Joseph Davis, Eswaran Subrahmanian & Art Westerberg, "Knowledge Management", Physica-Verlag (2005). ISBN 3-7908-0081-3

The papers included in this volume were selected from a collection of papers presented at an invitation-only workshop entitled 'Knowledge Management (KM) and the Global Firm: Organizational and Technological Dimensions' held at the University of Sydney in Sydney, Australia in February 2003. The following topics are discussed in these papers: concept of knowledge management and modes of sharing it, explaining the role of IT systems; empirical research on knowledge creation within social environments; and five reflective and useful contributions from practitioners actively engaged in knowledge management related endeavors.

3. Päivi Haapalainen, "Learning within Projects: A Qualitative Study of How Learning Contributes to Knowledge Management in Inter-Organizational Construction Projects", Acta Wasaensia No. 179, Industrial Management 14, Universitas Wasaensis 2007. ISBN 978-952-476-191-8

This PhD dissertation gives an extended explanation of learning in projects and within projects. It also investigates learning in inter-organizational projects as a part of the knowledge management of the project. It is typical for these projects that the project team consists of people from different organizations with different education and background. Public construction projects are good examples of inter-organizational projects and two case studies are carried out to understand how is knowledge related to knowledge management in the case of construction projects and how this learning can be facilitated using facilitated tool activities.

4. David A. Garvin, "Learning in Action: A Guide to Putting the Learning Organization to Work", Harvard Business School Press (2000). ISBN 1-57851-251-4

In this book, Garvin offers a complete overview of learning organization concepts. He introduces three models of learning - intelligence gathering, experience and experimentation - and shows how each mode is most effectively deployed. These approaches are brought to life in richly detailed case studies of learning in actions at organizations such as Xerox, L.L. Beam, the U.S. army, and GE. The book concludes with a discussion of the leadership roles that senior executives must play to make learning a day-to-day reality in their organizations.

References

- ↑ John Girard, JoAnn Girard (2015), "Defining knowledge management: Toward and applied compendium", Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management. Retrieved 11.09.2016, Available Online

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Jill Owen, Frada Burstein & Steven Mitchell (2004). "Knowledge Reuse and Transfer in a Project Management Environment", Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research, 6:4, 21-35, DOI: 10.1080/15228053.2004.10856052. Retrieved 12.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Audrey S. Bollinger, Robert D. Smith (2001). "Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset", Journal of Knowledge Management. Retrieved 11.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ E.D. Love; Edum-Fotwe; Irani, Zahir (2003). "Management of knowledge in project environments", International Journal of Project Management. Retrieved 14.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ Nahid Hashemian Bojnord, Abbas Afrazeh (2006). "Knowledge management in project phases", Proceedings of the 5th WSEAS International Conference on Software Engineering, Parallel and Distributed Systems. World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society (WSEAS). Retrieved 14.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ qualitydigest.com PDSA,Retrieved 17.09.2016 Available Online

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Health Partnership Division (August 2016), "PDSA: Plan-Do-Study-Act", Minnesota Department of Health Journal. Retrieved 14.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tim Kotnour, (2000), "Organizational learning practices in the project management environment", International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, Vol 17 Iss 4/5 pp. 393-406. Retrieved 11.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bastian Hanisch, Frank Lindner, Ana Mueller and Andreas Wald (2009). "Knowledge management in project environments", Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 13 Iss 4 pp. 148-160. Project Life Cycle,Retrieved 17.09.2016 Available Online

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 David A. Garvin (1993). "Building a Learning Organization", Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 12.09.2016. Available Online

- ↑ William R. King (2008). "Knowledge management and organizational learning", Omega-international Journal of Management Science, 2008, Volume 38, Issue 2, pp. 167-172. Retrieved 14.09.2016. Available Online