Post-Project Review

(→Planning Process) |

(→Review Amnesia) |

||

| Line 114: | Line 114: | ||

===Review Amnesia=== | ===Review Amnesia=== | ||

| − | + | ||

Considering the theory of Von Zedvitz, a post-project review's objective is to ensure knowledge generation for future projects <ref name="orglearning"/>. However, despite the tool's purpose, utilization of PPR lacks in organizations. A study conducted by Schindler and Eppler (2003), states that conducting "a successful post-project review requires personnel that are willing to invest time, having the right motivation, as well as the individual skills and the discipline"<ref name="harvest"/>. | Considering the theory of Von Zedvitz, a post-project review's objective is to ensure knowledge generation for future projects <ref name="orglearning"/>. However, despite the tool's purpose, utilization of PPR lacks in organizations. A study conducted by Schindler and Eppler (2003), states that conducting "a successful post-project review requires personnel that are willing to invest time, having the right motivation, as well as the individual skills and the discipline"<ref name="harvest"/>. | ||

Revision as of 16:19, 25 February 2018

When finalizing a project and providing a deliverable, a project manager does not necessarily know if the project can be considered a success. Thus, a methodology to gain tacit-knowledge can be done by using Post-Project Reviews (PPR). PPR is a tool to "evaluate project results in order to improve future projects methods and practises"[1]. It is arguably a tool within the uncertainty perspective, as the purpose of the tool is to analyze potential failures and successes of a project. The knowledge gained can lead to minimized risk by possibly optimizing and/or preventing mistakes in subsequent projects.

Despite the usefulness of the tool, there is no fixed framework of how to conduct it. Organizations operate differently and do have a tailored methodology for execution of the review [2]. Different studies depict recommendations of measures to apply before closing a project and conducting a PPR, as well as the methodology on how to conduct it. A project manager follows a set of interrelated actions in order to provide the desired deliverable, and do mainly follow the five categories known as Project Management Process Groups: Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring/Controlling and Closing [3]. Simultaneously, a successful application of PPR must follow these steps. If a project manager defines the different criteria for success or failure of a project, as well as applying strict quality management during the project; An easier application of PPR can be assessed [4]. Furthermore, the review can be conducted by a combination of team-members and external facilitator. Lastly, there are two recommended debriefing methods which are process-based and documentation-based. Process-based methods are debriefing methods that address the key learnings experienced during a project, and documentation-based methods"are methods on logging the knowledge obtained [1].

This article focuses on the purpose fo the tool, as well presenting a methodology of applying PPR considering a new product development project. Furthermore, the article argues who are responsible for applying the tool and depict the many barriers against it.

Contents |

Big Idea

Post-Project Review to improve organizational learning

Post-Project Review is a formal review or a meeting of an ended project, examining the lessons that may be learned and used to the benefit of future projects [1][5]. The purpose of the tool is to provide project managers with an overview of the success and failure modes from an ended project. The introduction of evaluation guidelines to an organization should lead to a more efficient way to manage projects as previous issues can be avoided, and safe solutions can be applied repeatedly. Furthermore, the experience from a project is documented in such a way that it is available for everybody to use it in future projects and not just linked to key employees who might not be present in the future[2].

The tool can be considered within the domain of uncertainty, as one of the four perspectives on how to do projects. PPR is a tool to acknowledge lessons learned from a project, and a method that emphasizes reflections. Application of the tool gives an additional possibility to adapt to other processes and increase people's competencies and awareness to issues [6].

PPR is a tool that can be utilized in any type of project and has clear benefits regarding gain of knowledge and lessons learned. The tool is a way for an organization to increase the tacit-knowledge sharing, as the knowledge shared is based on experiences and not facts [7]. Considering the different types of projects conducted, the PPR is a method emphasized especially within the domain of new product development and R&D projects. Product development is a time-consuming process, and the learning curve is depended on knowledge-sharing. According to Goffin and Koners (2011), it is "necessary to pass the knowledge of lessons learned between project teams in order to improve the performance of product development"[7].

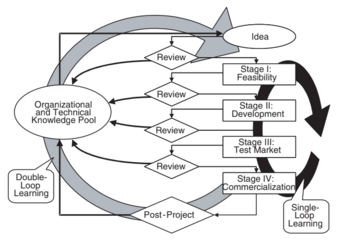

Von Zedvitz (2002) goes even further when defining what type of learnings that are generated when conducting a PPR, by stating that "post-project review focuses on the link between team-learning and organizational learning" [1]. The idea is that PPR do not only provide single-loop learning but double-loop learning. Single-loop learning considers "detection and corrections of mismatches between experience and a reference system without questioning or altering the value of the system". However, double-loop learning considers the detected "mismatch and implements measures to correct the reference-system" [8]. PPR allows organizations to gain knowledge from project-specific experiences, and then make it available to a "corporate-wide pool of organizational and technical knowledge pool"(as displayed in figure 1) [1].

Lack of Framework

Despite the tool's purpose, there is no standardized framework provided on how to conduct it. The reason for that is that all organizations operate differently, and may have a strategical aim that differs from other competitors. Thus, it is not possible to give a step-by-step description of how to conduct the review. Furthermore, this means that there is no literature that clearly depicts who are responsible for conducting the review (This is further discussed in section 3.1).

There are different studies published that depict their method of conducting a PPR. A study conducted by Schindler and Eppler (2003) states that organizations lack a clear and systematic way of logging knowledge obtained from projects. Thus, they have recommended two debriefing-process methods for the post-project review, which is: process-based and documentation-based methods. Process-based methods are the methods of acquiring the lesson learned from concluded projects, whereas the idea is to gather the project-team to answer four main questions [2]

- What was supposed to happen?

- What actually happened?

- Why were there differences?

- What can you learn from this experience?

Secondly, the document-based methods aim is to learn from the project experiences gathered. Documentation-based methods focus on aspects of experiences gathered from current project with knowledge gathered throughout the history of the organization. There are mainly three ways of documenting the lessons learned [2]:

- Micro Articles

- Learning Histories

- RECALL

Micro-article is a short article that depicts topic and project description, where the main trait is that there are graphical representations of the key learnings. Furthermore, Learning Histories are dense reports that provide more context or remarks of learnings obtained. Lastly, RECALL is an individual documentation method where participants address their personal learnings. It is important to emphasize that this is one out of several studies on how to conduct a PPR. The tool contains high-flexibility considering how to use it, and is mainly depended on the type of projects and how the organization operates regarding [2].

Utilization of Post-Project Review

The previous section states that there is no fixed framework on how to conduct a post-project review. The purpose of the tool is to ensure knowledge-sharing between project-teams and increase efficiency and effectiveness of execution of future projects [9]. Conducting a PPR requires a foundation of criteria, that are considered before and during a project. A study conducted by Anbari et. al (2008), provides a detailed overview of measures to be applied to the processes of a project. The process groups are according to the PMBOK guide defined as following [3]:

- Initiation: Defining a new project or a new phase of an existing project, as well as obtaining authorization to initiate a phase

- Planning: Development of a scope statement that clarifies future decision-making in order to attain the objectives.

- Execution: The processes initiated in order to complete the work

- Controlling: The measures applied to maintain, review and regulate the progress

- Closing: Finalizing all activities and closing the project

Initiation Process

When starting or pursuing the next phase of a project, a careful analysis of which criteria to measure against success or failure of a project should be conducted. Typically applied criteria are if project deliverable is given on-time within the budget, as well as it satisfies the different technical and legal specifications. These type of criteria are according to Project Management Institute (PMI) considered the "triple constraints", as these criteria consider scope, time and cost. Projects considering triple constraints theory may be helpful for future project managers to determine the most effective approach to address a certain issue [4].

Planning Process

During the process of establishing the scope of the project and refining the objectives; It is according to Anbari (2008) recommended to "use quality planning tools in order to ensure customer involvement with project team" [4]. Examples of quality planning tools are Quality Function Deployment (QFD) which aids management to identify customer needs, wants expectations and translates it into a technical recommendation. Another tool is multi-criteria decision-making to Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) that considers subjective values to different components and technical project deliverables. Utilization of quality management tools decreases the chances scope creep, cost overruns and specification gaps. [10] [4].

Executing Process

Considering that the quality management tools are applied by the management in the two first process groups, a solid foundation for PPR is provided as it gives a clear overview over the different criteria for successes and failures. Furthermore, the quality management tools aid a proper execution of the project as it clarifies the certain expectations the project customer and/or final user has to the deliverable [4].

Monitoring/Controlling Process

Given that the use of quality management tools was insufficient and was the cause of quality deficiencies; The recommendation is to use to quality improvement approaches. Examples of improvement approaches can be the six sigma method, seven-step method, benchmarking, quality audits etc. The idea behind these methods is to identify causes for quality deficiencies and analyze which measures to apply in order to meet customer expectations [4].

Closing Process

The last process is about providing the project deliverable. Usually, a deliverable is considered a success if the triple constraints are satisfied [4]. Considering all the measures from previous processes are applied, a project manager will have a solid foundation to define the potential wrongdoings in the project. Hence, a PPR can be initiated wherein it can be conducted by for instance the debriefing methods stated in section 1.2 (process-based and documentation-based).

Application

As outlined in the abstract, the application of the PPR will be analyzed from a new product development perspective. Section 1.2 emphasized that the tool is yet to be standardized, and different organizations conduct it differently. Thus, one can not depict a certain framework of how to perform a PPR.

A recommendation of what measures to apply before conducting the review is given, however, how to conduct the review after a project-end are yet to be defined. Before conducting the review itself, a project manager should apply the different measures in order to have a solid foundation of criteria for the review.

This section describes an application method for PPR in light of a product-development project.

Framework for Post-project review in a product-development project

A study performed by Goffin et at. (2010) suggests four focus areas to better leverage knowledge generation in an organization that strives for product development. The focus areas are following [7]:

- Facilitation-method of PPR that stimulates and emphasizes tacit knowledge

- Foster individual learning

- Team members to act as knowledge brokers

- Project kick-off meetings as an opportunity to review

Facilitate PPRs to Stimulate Tacit Knowledge

When conducting the PPR, an experienced facilitator should be hired. An experienced facilitator is able to successfully apply a stimulating environment, wherein the facilitator is able to guide the discussion and generate tacit-knowledge within the team and the organization [7]. Experienced facilitators are known for using tools that make participants creative and motivated, thus, the ability for improved knowledge-sharing [8].

Foster Individual Learning

Project-managers developing new products must ensure that the team-members possess the necessary motivation to strive for more learning. Knowledge may be obtained in several ways. It can be direct project experience, mentoring, participation in communities of practice or even individual reflection [7]. R&D professionals need to be encouraged to develop their expertise. By doing so, the team will have a better base on executing the project, as well as more knowledge to share with the other teams [11]

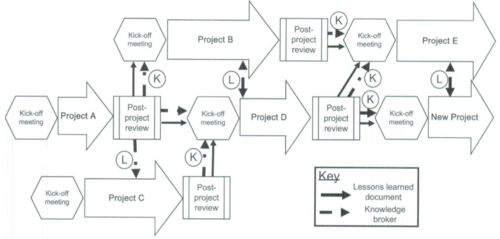

Designate Knowledge Brokers

Project personnel should emphasize members to transfer specific learning between each project. This method will make project-to-project learning more tangible [11]. Furthermore, applying the method will ensure prevent knowledge-gaps in future projects [7].

Use Project Kick-Off Meetings

Considering the planning process, where the project scope and objectives are defined; It is recommended to have a kick-off meeting in order to ensure the correct motivation and mutual understanding of what the project has to deliver and understand the objectives [7].

An On-Going Process

The four main steps to perform in a product development project can be considered a reverse post-project review framework. The mission is to ensure that key-learning are to be shared between project-teams in order to aid future projects. The framework starts with having a kick-off meeting before executing a project, wherein a PPR is conducted with an experienced facilitator after the end of a project. Further on, knowledge brokers from the PPR inform the kick-off meeting for the project. This description is further illustrated in figure 2, as it clearly displays how knowledge-brokers share lessons learned from a PPR to a kick-off meeting.

Thus, the product-development PPR framework can be considered an on-going evaluation that emphasizes tacit-knowledge. Organizations execute projects differently, however, it is common that knowledge generated in any project-execution is done by failing. Therefore, it is important to have a work environment that is not judgemental, but rather open [1].

Limitations

Despite the benefits of executing a post-project review, there are uncertainty on whom are responsible of conducting the review (as mentioned in section 1.1). As organizations operate and conduct the review differently, it is not possible to define if it is a project, program or portfolio manager that is responsible. Furthermore, studies shows that organisations shows skepticism towards the use of it. This section discusses who is responsible for conducting PPR, as well as describing the reasons of why the tool is not being used to a full extent in organisations today.

Responsibility of Post-Project Review

According to PMBOK guide, the responsibilities of a project manager is to ensure that the project led will generate value for the organization, and adapt to the many changes in the environment, competition and marketplace. A project is a temporary endeavour wherein the purpose is to provide a certain deliverable [3]. A project is ended when a deliverable is provided, however, it can also be deemed done if objectives cannot be met. In cases where failure is obtained in a project, a post-project review can provide the root-causes for it.

Studies do not depict directly who are responsible for applying the tool. Previous section states that PPR is conducted in the closeout of a project, however, there is no literature stating whether it is a project, program or portfolio manager that are responsible for it.

Referring to section 1.1; Post-project review does generate better organizational learning. Thus, one can argue that the main responsible manager of the review are the managers initiating the projects. According to MSP (Managing Successful Programmes) framework, a post-project review is an activity under the domain of program management, with the "involvement of project-team members, project manager and external personnel" [12]. Incorporating all these members will according to MSP "capture successes and problem areas associated with the execution of the project" [12].

The program manager considers not only the project deliverable, but also what benefits are gained from all projects within the program [13]. Program manager ensures coordination of project execution. Summarily, one can argue that the project manager is responsible for the quality of the review, and the program manager is responsible for review-execution and newly obtained knowledge is shared to the upcoming project. This view can be coherent to the framework presented in the previous section, as project managers perform the review and the program manager ensure that the knowledge gets shared.

Review Amnesia

Considering the theory of Von Zedvitz, a post-project review's objective is to ensure knowledge generation for future projects [1]. However, despite the tool's purpose, utilization of PPR lacks in organizations. A study conducted by Schindler and Eppler (2003), states that conducting "a successful post-project review requires personnel that are willing to invest time, having the right motivation, as well as the individual skills and the discipline"[2].

These abilities may be hard to require from personnel after a project-closeout. The main reasons for the lack of PPR in organizations are due to scepticism regarding the benefits of it. Project manager and team tend to have difficulties understanding the value created by performing such a review, and rather consider it costly and time-consuming [5].

Usually, there is high time pressure of finalizing the project, including tasks that await completion. According to Busby (1999), "project managers want to minimize cost allocated to their project in general, especially towards the end" [5]. As addressed earlier, the project manager is hired to provide a deliverable within a certain time-frame. Thus, project manager tends to not see the value for their own project by conducting a PPR, as the benefits from the review are for the future projects and not the current one. Therefore, it is important for a program manager to ensure that project manager and team understand the benefits generated for the organization and the program by using PPR.

Program managers need to use the necessary time to ensure better sharing of projects, either by performing the documentation themselves or allocating responsibility of the documentation to employees that can see the value of knowledge-sharing. A method of increasing motivation is to graphically show the long-term benefits that are obtained by performing such a review [5]. Program managers goal is to ensure that projects provide a deliverable that together will provide the program desired benefit.

According to Schindler and Eppler (2003) project managers tend to have a weakness of admitting their wrongdoings [2]. Therefore, they prefer to pursue the next project rather than analyzing potential mistakes from the previous one. For PPR to be favourably performed, the mindset of the managers must change. A suggestion would be that program and portfolio managers apply measures, showing that failure can lead to success [1].

Requiring the skills and discipline to conduct such a review is of high importance, however, Von Zedwitz (2002) discovered that personnel do have troubles of providing objective reflections upon past actions and their consequence [1]. Furthermore, participants tend to repress experiences as they may be uncomfortable to share it. Maintaining social relationship do usually matter for most people, and management is afraid of a post-project review being a platform to blame, criticize and recriminate each other [4].

Annotated Bibliography

- Von Zedtwitz, M. (2002). Organizational learning through post-projects reviews in R&D. - The author has several acknowledgments regarding R&D innovation and development considering organizational changes. The article depict how organizations benefits from using post-project review, as well as how to incorporate the tool. Furthermore, it adresses why R&D organizations are sceptical against conducting the tool.

- Schindler M. and Eppler M. (2003). Harvesting project knowledge: a review of project learning methods and success factors - The article depict the proven methodologies on harvesting knowledge obtained from ended projects. Furthermore, the article depict on the benefits given to the project manager by applying the debriefing methods. Lastly, a recommendation for implementation is provided.

- Busby, J. S. (1999). An assessment of post-project reviews. Project Management Journal - The article is published on the Project Management Journal and depict how project-teams obtain knowledge and how they are able to share. Busby compares the tool with the reality of why it is not being fully used, and provides suggestions on how to adapt to the challenges.

- Anbari F., Carayannis E. and Voetsch R. (2008). Post-project reviews as a key project management competence - The article compare knowledge management with project management. It further adresses how success from previous projects affects future project, and in what way the knowledge obtained do provide an improved future project-execution. Lastly, it depict the barriers against the tool.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Von Zedtwitz, M. (2002). Organizational learning through post-projects reviews in R&D. International Institute for Management Development [online]. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9310.00258/full

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Schindler M. and Eppler M. (2003). Harvesting project knowledge: a review of project learning methods and success factors Institute for Media and Communication Management [online]. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0263786302000960

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Project Management Institute (2013). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. 5th ed. Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Anbari F., Carayannis E. and Voetsch R. (2008). Post-project reviews as a key project management competence Department of Information Systems and Technology Management [online]. Available at: http://production.datastore.cvt.dk/filestore?oid=539b961a4179934d1f03f6e4&targetid=539b961a4179934d1f03f6e6

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Busby, J. S. (1999). An assessment of post-project reviews. Project Management Journal, 30(3), 23–29. [online]. Available at: https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/assessment-post-project-reviews-5308

- ↑ Geraldi J, Oehmen J., Thuesen C. and Stingl V.(2017). How to DO projects: A Nordic flavour to managing projects. Danish Standards Foundation.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Goffin K. and Koners U. (2011). Tacit Knowledge, Lessons Learnt, and New Product Development. The Journal of Product Innovation Management.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rasmussen L.B. (2011). Facilitating Change using Interactive Methods in organizations, communities and networks. Polyteknisk Forlag.

- ↑ Kransdorff A. (1996). Using the benefits of hindsight - the role of post-project analysis. The Learning Organization. Vol 3 Issue 1: p.11-15. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/09696479610106763

- ↑ Rolstsdås, A., Olsson, N., Johansen, A., & Langlo, J. A. (2014). Praktisk prosjektledelse. Bergen: Fagboklaget Vigmostad & Bjørke.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Carillo P., Choudhary A. and Harding J. (2011). Knowledge discovery from post-project reviews. Construction Management and Economics [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2011.588953

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 AXELOS and Cabinet Office. (2010). Managing Successful Programmes. 2011 edition. The Stationary Office Ltd.

- ↑ Project Management Institute. (2008). The Standard For Program Management. Project Management Institute.