Emotional Intelligence and Leadership

(→About Emotional Intelligence) |

(→Applications of Emotional Intelligence in Leadership) |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

=== Focusing on the Important Things === | === Focusing on the Important Things === | ||

| − | ... | + | In order to focus on the important things, leaders need to permanently prioritize their own, as well as their team’s working activities <ref name="PMI_ProjM"\>. This task ultimately comes down to making good decisions when faced with a (large) set of alternatives. In the following, the influence of feelings in this matter shall be examined in more detail. |

| + | |||

===== Importance of Emotions in Decision Making ===== | ===== Importance of Emotions in Decision Making ===== | ||

Revision as of 21:44, 15 February 2021

Felix Vinzenz Wütherich, Spring 2021

Contents |

Abstract

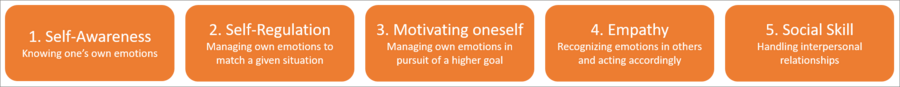

Emotional Intelligence (EI) has received significant attention both in the scientific and broader community for its potential influence on professional and private success. Several models exist, however the dominant domains of EI in the popular literature are (1) self-awareness, (2) self-regulation, (3) motivation, (4) empathy, and (5) social skills. This article aims at linking features of EI to distinct challenges in leadership, as well as deriving key insights for practitioners in the field of project, program, and portfolio management. Acknowledging that the tasks of a leader are subject to a great variety, three distinct areas are addressed.

Firstly, leaders must choose their own and their team’s priorities among a set of alternatives, which are often generated by large quantities of information coming in at fast speeds. It is discussed that emotions do not degrade decision making per se, as the popular opinion might suggest. Rather, the absence of emotions in decision making can substantially lower the quality of decisions. Further, the influence of positive and negative emotions on decision making is considered, as they can lead to very differing outcomes.

Secondly, leaders need to communicate appropriately to their followers. This is especially crucial when giving and receiving feedback. Emotionally intelligent leaders are aware of their followers’ emotions and manage them appropriately when giving feedback. Likewise, leaders are able to accept feedback gracefully through high levels of self-awareness and self-regulation.

Thirdly, leaders are responsible for building effective teams. They can do so by using empathy and further managing their followers’ emotional reactions to unforeseen circumstances. In addition, leaders should be aware of the influence of their own emotional display on their surroundings. Emotions can be subconsciously passed on to one another, through an effect labelled emotional contagion.

Critique regarding the young research area of EI stems from the fact that in an early stage, some inflated claims have been made in the popular literature that could not always be backed up empirically. Further, it is imperative to mention that “leadership” per so does not exist, but rather a variety of different leadership styles. There appears to be a relationship especially between EI and transformational leadership, of which the strength is however not agreed upon. In conclusion, while the importance of handling emotions in leadership is widely acknowledged, one should be careful about regarding EI as the “magic bullet” for successful leadership.

About Emotional Intelligence

When talking about intelligence, the first associations that are made typically refer to mathematical or linguistic skills, and “IQ” is a common term that subsequently comes to mind. However, a large body of literature suggests that there is no such thing as “intelligence” per se, but rather a multitude of types. One such type of intelligence is labelled “emotional intelligence” (hereafter referred to as EI) and has received significant attention for its wide implications on an individual’s private and professional endeavours – even to a degree where it is listed as a requirement in some job descriptions. The basic definition of EI was made by Salovey and Mayer in 1990, describing EI as the “ability to monitor one’s own and others’ emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use the information to guide one’s own thinking and actions” [1]. Salovey et al. further suggested five main domains which characterize emotional intelligence, which were later slightly modified and popularized to a large extent by psychologist Daniel Goleman [2] [3]:

1. Knowing one’s emotions / Self-Awareness. This is also referred to as self-awareness, meaning the ability to “recognize a feeling as it happens” [2]. A high degree of self-awareness is an enabler to recognize the effect of own emotions on oneself, as well as others, and act accordingly [3].

2. Managing own emotions / Self-Regulation, so that emotions match a given situation. This builds on the first domain since handling emotions first requires being aware of them.

3. Motivating oneself. This refers to managing emotions (domain 2) in pursuit of a higher goal, such as delaying gratification or resisting certain impulses.

4. Recognizing emotions in others / Empathy. Recognizing emotions in others through empathy also requires emotional awareness in the first place (domain 1). Empathic people have an advantage at understanding the “subtle social signals” which express the needs and wants of others [2].

5. Handling relationships / Social Skills. This task essentially breaks down to the management of emotions in other people. It holds wide implications for any type of interpersonal interactions and is therefore of particular interest when examining emotional intelligence and leadership.

While this first model is known more to the popular audience, it has been criticised for blending personality characteristics with the underlying link of emotions and cognition in EI [4]. However, since it is rather likely that practitioners of project, program and portfolio management will come across Goleman’s model of EI, the further discussions in this article are mainly based on this model.

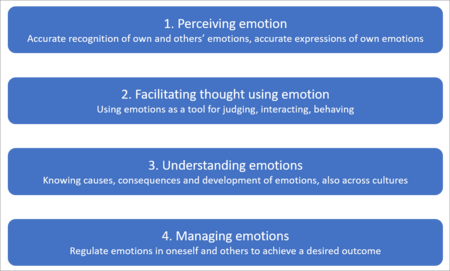

An alternative, more distinct model based on individual abilities was put forward by Mayer and Salovey in 1997 [5], which they also updated in 2016 [6]. It appears to have a higher standing in the scientific literature on EI, and to draw as complete a picture as possible, this "ability model" is also introduced in the following. The model encompasses four branches. These in turn include certain types of reasoning, of which some examples are given below:

1. Perceiving emotion: This relates to accurately identifying and expressing one’s own emotions, as well as correctly identifying others’ expressions.

2. Facilitating thought using emotion: Using emotions to set the right priorities in thought, make the right judgments and relate to other people.

3. Understanding emotions: Knowing how people feel in the present and might feel in the future given the circumstances, as well as recognizing cultural differences.

4. Managing emotions: Effectively handle one’s own as well as others’ emotions to achieve a certain goal.

Throughout this article, the term “feelings” is used for both emotions and moods. Emotions are shorter-lasting and triggered by circumstances that are usually easy to identify. Moods on the other hand are feeling states that last longer and are not specifically tied to a certain trigger. [7]

Applications of Emotional Intelligence in Leadership

Focusing on the Important Things

In order to focus on the important things, leaders need to permanently prioritize their own, as well as their team’s working activities Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Cite error:

<ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found