Matrix Organizations

Contents |

Abstract

An organization can be defined as a group of people who work together in an organized way for a shared purpose [2]. The way an organization is structured can affect the number of resources available for the organization as well as how different projects are carried out [3]. At the beginning of the 20th century, many organizations obtained their ways of working, either by structuring their work with a larger focus on projects (projectized structure) or groups with similar roles and expertise (functional structure). In the 1960s aerospace organizations saw a need of adopting a new approach that would combine the knowledge from various industries, and the third approach, called matrix organization, was found.

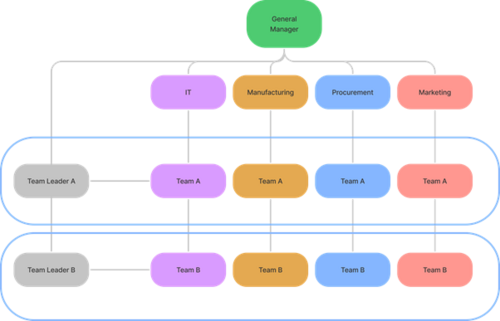

Project Management Institute defines Matrix Organization as any organizational structure in which the project manager shares responsibility with the functional managers for assigning priorities and for directing the work of persons assigned to the project [3]. This means that in matrix organizations there are generally two managers to report to, and the managers must collaborate for better resource allocation, as well as knowledge-sharing. Matrix organizational structure is commonly applied when an organization is focusing on projects and technical support across different functions and fields is needed [4]. An illustration of an organization with a matrix structure is shown in Figure 1.

Generally, there are three types of matrix organizations, based on the influence of each manager:

- Weak matrix: the matrix has a high functional-manager influence and weak project manager link to the project. The staff mainly reports to their functional manager who is the main decision-maker in the process.

- Balanced matrix: the matrix has both functional and project manager involvement, although the functional manager has authority over the resources of the project. The staff reports to both functional and project managers.

- Strong matrix: project manager's link to the project is dominant. Project manager has most influence on decision-making process, resources and task allocation.

The project manager’s involvement in the activities determines the strength of the matrix organization.

Overview of matrix types and characteristics

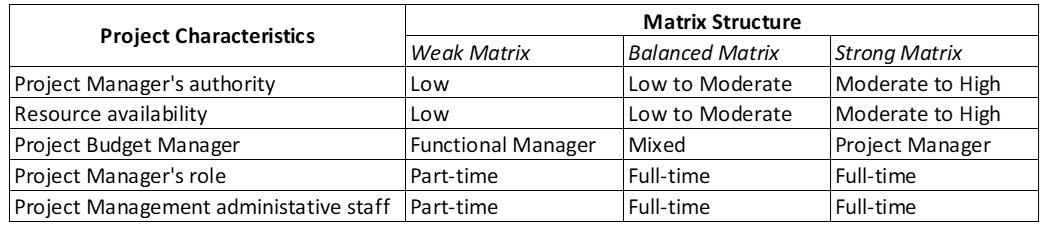

An overview of the matrix types and project characteristics is illustrated in Figure 2 [3].

From three types of matrix organizations, the weak matrix has low project manager’s authority, and mostly the authority comes from functional management. Resource availability is low and the project’s budget holder is the functional manager. The project manager’s role and their administrative staff are part-time.

When the strength of the matrix is increased, the project manager and their administrative staff work with the team full-time. This means that their involvement in the project is increased, and most of their work revolves around this team.

A balanced matrix from its name implies that the strength between the project manager and functional manager is balanced. Both parties collaborate together, however, the functional manager still has higher control in the decision-making.

A strong matrix suggests that the project manager has the most authority over the project and its budget. Resource availability is also increased, from low-to-moderate to moderate-to-high.

Application

Matrix organizational structures are often complex and require managers that can oversee several units within the project. Moreover, the environment in which matrix organizations are applied successfully is unpredictable and complex, such as medicine or space industries [5]. According to Slack et al. (2016), matrix organizations require four main characteristics [6]:

- Communication between managers. All managers that are participating in the project development must communicate effectively for better decision-making and resource allocation.

- Management conflicts. A formal policy of managing conflicts must be developed to avoid confusion when a conflict arises.

- Commitment. The project team must clearly understand why such structure is implemented in the organization and how it contributes to the development of a product or service. The team should be committed both to the project(s) as well as their department.

- Role of project management. The project manager has a role of coordination which involves the planning of the resources, budget, and time.

Strengths and weaknesses of matrix organizations

There are contradicting opinions on the different strengths and weaknesses of matrix organizations. Research suggests that different authors can see the same characteristic of a matrix organization both as a strength and a weakness [7]. The main advantages associated with the matrix organizational structure include efficiency, both in terms of resource allocation and information flow. Staff can be fully sourced to a project and also contribute to other parts of the organization, such as their functional department or other projects. The information flow is more transparent, allowing the organization to share the knowledge and see the progress of each functional team. Matrix organizations are also possessing stronger project characteristics, since the structure allows for better project management practices [8].

Because matrix organizations involve a lot of planning around administrative changes and staff resource allocation, the main disadvantage is the high administrative costs. However, if the matrix organization is mature, the additional overhead costs even out due to an increase in efficiency [9]. The matrix organization involves a line and project reporting manager, which can potentially cause a conflict if the expectations and conflict management are not clearly defined [8]. This essentially can mean that staff must understand how the managers work together as well as how the reporting must be executed. Staff in matrix organizations can also work on several projects at the same time, causing a disadvantage in understanding who to report to.

How to make the matrix organization work

McPhail suggests six steps in making the matrix organization work [10]:

- Conduct Goal Alignment. Employees in the organization must work together towards the mission and have a common sense of the goal. The management team has to clearly define the vision of the project as well as the key priorities.

- Define the Matrix. Matrix organizations are project-oriented, therefore the resources associated with the projects must be set and prioritized. Moreover, many projects can mean higher complexity in project management, which requires a clear plan for making the projects successful.

- Establish Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). A clear definition of KPIs in an organization can show how the performance is being measured as well as the current progress over the specific project. It allows different managers to track the status quo of the objectives and compare it to the objectives set by different project and functional managers. It is the staff's responsibility to deliver on KPIs within the allocated time and budget of the project. The tracking process of KPIs can be easily visualized with different dashboard tools (both company-specific tools as well as publicly available resources).

- Conduct Role Clarification Sessions. Often employees in an organization might feel confused when to report to a certain manager and when the progress of a project must be documented. When roles are clarified, employees have a clear understanding of the responsibility and expectations from higher management. When the roles are not aligned, teams can often experience conflicts causing waste of resources and effectiveness.

- Provide Professional Development. When a project is finished, an employee can be sent to work on a different project with different expectations and skillset. When an organization provides professional development, employees can avoid misunderstandings as well as improve their knowledge on areas that are less known to them. Professional development must be provided by senior staff and team members should be involved in the process of identifying the needs for the next project.

- Build a Culture of Trust. Matrix structure involves multiple managers and teamwork, therefore nurturing the trust within the organization is essential. When the culture of trust is not built, the teams are directly affected by problems of conflicts and mistrust in the organization as such. McPhail suggests several tools that can enhance trust, for example, project kickoff meetings, personality assessments of project teams, social events, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and tracking of the project success.

Adopting these six principles can improve the matrix organization in a business. However, it is not enough to adopt the principles once and think that the organization will succeed. Continuous improvement over the organizational work as well as reviewing the principles is required for making the matrix organization work.

Conclusion

Matrix organizations are complex and a need for a clear structure of making them work in practice is apparent. The matrix organizations are utilized the best in complex and uncertain environments, where resource allocation is required for different projects. There are many advantages associated with matrix structures, such as improved efficiency, better information flows across functions in the organization as well as clear project-oriented goal alignment. Some of the disadvantages include complexity in reporting to several managers, potential conflicts that might arise due to several manager involvement, as well as higher administrative costs for the organization. Several reports suggest that a need for further research of redesigning the matrix organization for modern organizations is required [8], [7], [4]. Great control over conflict management, resource allocation, and clear objectives makes the matrix organizations successful and thriving in the modern world.

Bibliography

- ↑ Moodley, D., Sutherland, M., & Pretorius, P. (2016). Comparing the power and influence of functional managers with that of project managers in matrix organisations: The challenge in duality of command. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 19(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v19i1.1308

- ↑ Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Citation. In Cambridge English Dictionary. Retrieved February 11, 2022 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/organization.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), Fifth Edition ed., Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, Inc., 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kuprenas, John A. Implementation and performance of a matrix organization structure. International Journal of Project Management 21 (2003), p.51-62

- ↑ Burton, R. M., Obel, B., & Håkonsson, D. D. (2015). How to get the Matrix Organization to Work. Journal of Organization Design, 4(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.7146/jod.22549

- ↑ Slack, N., Brandon-Jones, A., & Johnston, R. (2016). Operations Management (8th ed.). Pearson Canada.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Goś, K. (2015). The Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Matrix Organizational Structures. Studia i Materiały Wydziału Zarządzania UW, 2015(2), 66–83. https://doi.org/10.7172/1733-9758.2015.19.5

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Cristóbal, J. S., Fernández, V., & Diaz, E. (2018). An analysis of the main project organizational structures: Advantages, disadvantages, and factors affecting their selection. Procedia Computer Science, 138, 791–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.103

- ↑ C.J. Middleton, “How to Set Up a Project Organization,” HBR March–April 1967, p. 73.

- ↑ Johnson McPhail, C. (2016). From Tall to Matrix: Redefining Organizational Structures. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 48(4), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2016.1198189