Pooled, Sequential & Reciprocal Interdependence

Written by Tolga Azgun

Abstract

A project consists of systematic essential features in all levels that interacts with each other. The way and quality of interactions shape the level of complexity. Although this complexity cannot be fully controlled, project teams can be designed and adapted to coordinate the origins that arise as a consequence of complexity. [1] Large scale projects encompassing various cross functional business units or teams have been characterized through their structural complexity.These complexities occur due to uncertainties which often is a direct consequence of vacillating resources (e.g., insufficient information flow) streaming throughout the project team.[2] These resources vary from team to team and can be crucial for the success of the overall performance.These interlinkages of workflow between groups were conceptualized by Thompson (1967) [3] naming them “interdependencies”. The term can be defined as the extent to which groups, business units or teams are interdependent with one another and are essentially dependent upon the action of others for their success. Interdependencies were categorized according to the severity of their dependence to one another. An additional area of interest for scholars has been external interdependencies.(e.g., buyer-supplier relationships) These relationships indicate specific firm level dependencies where being dependent on another is seen as an integral part and as “boundary spanners” for successful cooperation between companies. [4] However, this article aims to illustrate dependencies from an inter-organisational point of view, in which contrasting historic concepts of interdependencies will be reviewed. Furthermore, it is aimed to highlight the groundwork of the notion constructed by Thompson (1967)[5] in introducing the following concepts: pooled, sequential, and reciprocal interdependence. In addition, the article will outline the need of differing coordination methods for varying interdependency types based on the intensity levels to reduce the uncertainties which arises through complex workflow patterns.

Contents |

Big Idea and Literature Review

J.D Thompson’s work Organizations in Action” is seen as the foundation of characterizing organizational groups and has been inspirational for scholars studying the organizational design field. [6] Consequently, elementary theories of the book “Organizations in Action” developed itself into having universal acceptance within the field.

As the adoption of groups and teams is increasing within organizations [7] it is essential to realize the effect of different types of interdependences on group control mechanisms and results. Typically, harmony in relationships and interaction between group members improves performance, in contrary, variance inflates interpersonal costs as well as disagreements which will weaken the group efficiency.[8] Besides the work of Thompson (1967), much scholar’s research has been investigating the value of “management control” processes to complement synergies of teams and business units. [9] Adler’s (1995)[10] main research has been focusing on how coordination exigencies of interdependences differ over the time of a product development project’s lifecycle. The results showed that the growing innovation of a product and process scope needed more interactive management instruments. Ambos and Schegelmilch (2007)[11] have laid their focus on the effects of interdependence levels and respective control mechanisms like “centralization, formalization and socialization” and found out that with an expanding degree of interdependence the use of these measures were also growing. Macintosh and Daft’s (1987)[12] center of attraction was to detect the effect of differing formal control mechanisms according to interdependence models. The summarized outcome of the study presented that, in growing pooled interdependences the usage of classic operating mechanisms grew, whereas the usage of “setting up budgets and statistical reports” declined. On the other hand, in an expanding scope of sequential interdependences, the adoption of “budgets and statistical reports” have shown an increase. However, on intensifying reciprocal interdependences the use of both classic operating mechanisms as well as budgets, statistical reports have dropped. In general, the outcome of ongoing research has proven that high level interdependences among teams requires more control. This is mainly because of the difficulty in reviewing the particular input of a sub team to the general project success while actions and resources commonly influence each unit’s performance.[13] Therefore, planning and a suitable coordination between units in a project is critical in apportioning limited resources which could potentially hinder arising disputes for teams facing uncertainties. A suitable coordination strategy would allow a copious knowledge flow throughout the entire project which is essential for a flawless operation. [14]

Pooled, Sequential & Reciprocal Interdependecies According to J.D.Thompson

Interdependence can be described as the degree to which responsible units are contingent to one another because of the allocation or trade of mutual resources and actions to carry out objectives.[5] As mentioned previously, the most popular systematic classification of task interdependence was brought in by J.D. Thompson who detected three types of interdependence - pooled, sequential and reciprocal interdependence. J.D. Thompson has actively worked with the following Guttman-scale to categorize these types according to their complexities: If a company or unit only consists of pooled interdependencies, then the organization is of low complexity, if there are only sequential interdependencies existent, the organization is of medium complexity, last but not least if the reciprocal interdependence is the type dominating the project, a high level of complexity is expected. Furthermore, he suggested a scheme for categorizing technology kinds utilized by both production and service units in which he associated the organizational characteristics of unit or team to the following technology types: mediating technologies, long-linked technologies, and intensive technologies.

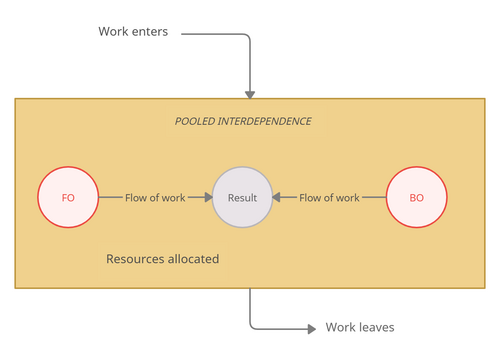

Pooled Interdependence

A pooled interdependency is the least intense dependency type and has the largest physical dispersal of team members out of the three proposed by Thompson. Thompson associated the mediating technology type with the organizational characteristics of pooled interdependence. It occurs when project teams split comparable resources and tasks but continue to work independently. However, the outcome of each member affects the whole project performance but does not hinder anyone else to proceed with their activities. Everyone of the team contributes to the overall performance with distinguished efforts and is backed by the entire team. Autonomous activities of each individual usually run parallelly and resources are allocated by a routine pool. Merging homogeneous resources and actions is mostly compelled by “economies of scale” to reduce costs. Therefore, this kind of resource interdependency originates when a great degree of consistency of resources are ready for use to accommodate the needs for taking decisions. The results can be mostly predicted beforehand.[2]

The cost of coordination for pooled resource and task interdependencies is relatively low compared to its contraries. This is mainly because of the low-level management requirements. The need of active collaboration and communication is little. One of the main mechanisms is driving standardization in patterned workflows or in operation processes throughout units. In pooled interdependencies, it is crucial to maintain the devotion of each individual by reminding them how their input will be unified at the end result. Integrating a “reporting process” in which the decision makers or managers can assign a specific part of the total project to a team member, having routine team discussion where processes and regulations are reviewed could boost the motivation of the members. A gymnastics team is one of the many examples which could represent a pooled interdependence where each team member has to actively render a distinct contribution in order to succeed in team rankings. Another example is a school where different teachers each take actively part to accomplish the overall goal, which is that pupils learn, they are however all independent in their classes while teaching to their students.

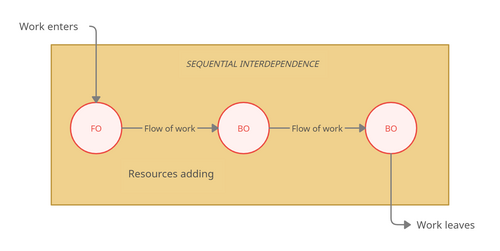

Sequential Interdependence

A sequential interdependence engages with workflows moving and operating between team members or units within a single direction. The sequence can be seen as a chain framework that helps the extension of the value stream. Thompson has associated the organizational features of the sequential interdependence type with a long-linked technology. The intensity level of a sequential interdependency is definitely larger than a pooled coupling. The units who are located in the downstream side of the chain are very much reliant on the success and completion of the task of the first members of the unit. The task distribution begins with an input workflow and is transferred to the next recipient. Hence the receiver unit or team member is highly dependent on the completion of the previous work. Due to the sequential construct, the input resource of the downstream member is provided by the upstream member or unit. However, the direction of the resource is never in the opposite direction. This leads to adding resources task by task throughout the value chain. The critical point which requires further attention for the coordination of a sequential interdependence is the transfer of a share of task or resource to the consecutive member down in the value chain. The effectiveness and smooth functioning of handing the task or resource to the next unit can be key in the overall success. A respective example for a sequential team interdependence can be a rugby or track team where each athlete has to run his or her part in the field and hand off the baton to the next member on the sequence before the consecutive member can start their part. Another interesting example is a manufacturing hall where certain outsourced materials must be first purchased by the procurement team and hand it over to the first station in the assembly line. After the first station is reached in the assembly station it is most probably sent to the next section where the product is tested.[2] To sustain the effectivity of an assembly line workflow or a sequentially structured unit some of the following coordination mechanisms are utilized in order to reduce the uncertainty. Standardization might be used to automate certain uncritical activities throughout the chain, however according to J.D.Thompson planning the workflow beforehand and scheduling a timetable should be used as a coordination method. Adding additional slack resources in the inventory for the case of an absence or failure is counted as one of the measures to cope with the uncertainty. Thompson took external firm-level interdependencies also into account in which he suggests “vertical integration” within the supply chain as a coping mechanism for buyer-supplier dependencies.[5] Integrating IT systems for scheduling and assisting the progress one-sided structure is seen as a critical point by bringing capabilities and competencies together for reaching functional agility.[2]

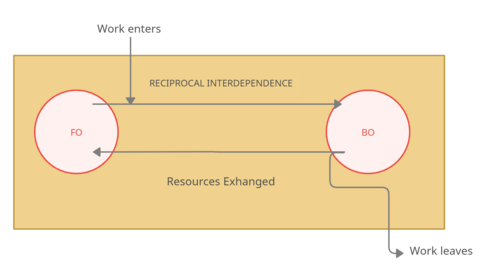

Reciprocal Interdependence

Reciprocal interdependence encapsulates sequential interdependences and is the most complex as well as the most intense interdependency type out of the three proposed by J.D. Thompson. It arises from activities and tasks flowing cyclical and in both directions throughout the value chain. Resources are mutually exchanged, and tasks are completed simultaneously, each team member working for a common objective. A unit’s output might become an input of the consecutive member and vice versa.[9] The lowest physical dispersal and the greatest level of collaboration is typically seen within a reciprocal interdependence. A good example of a reciprocal interdependent unit is a hospital team. A patient who was just delivered to an emergency room creates typically an extensive pressure on the team. The need of mutual interaction and collaboration suddenly increases, and the patient is sent to different test stations to find the root cause of the problem. Each station runs their tests parallelly working towards the same objective which is to save the patient. The importance of the coordination here lays in the mutual adjustment and comprehensive interaction between the team members. Another important coordination mechanism is to have respective specialists as well as experts which are capable of reducing the uncertainty of the situation. It is proposed to have certain “all-rounders” within the team that serve as a bridge function to sustain the interaction between distinctive experts. This is often neglected in teams where respective expert intel is not transferred correctly to the next person who might not have the same understanding of the topic. Since the costs of coordination would be very high for serving a broad sector, these teams usually prefer to operate on a narrow focus. J.D.Thompson has categorized this technology type as an “intensive” technology where there is no room for standardization and negotiation.[5] The essential objective of coordinating reciprocal interdependences is improving certain competencies. The role of IT has here is to ease the bidirectional exchange of resources and assist the mutual adaptation procedures.

J.D. Thompson has introduced an additional interdependence type after several years later naming it “intensive interdependence”. It’s correlation with respective coordination mechanisms has not been studied by scholars as comprehensively as the other three types. Intensive interdependences occur when miscellaneous resources and tasks are utilized in a direct teamwork. These resources usually arise as new packages for filling the existent resources to seek the overall objective. This is usually a collective intention mainly considering the economies of scope effect.[9]

Coordinating Interdependence in Cross-Functional Project Teams

Standartization of Work Processes

Standardization of workflows in a whole can be achieved when the work processes itself, the output as well as the input of the task is constructed beforehand according to the aligned standards. The input of the workflow consists of the talents and know-how of the worker.[15] As mentioned previously, standardization as a coordination mechanism is mostly suitable for pooled interdependences. By aligning the expectations (outputs) of each team member beforehand, each member’s output can be linked without difficulty to carry out the overall goal. The range of the output can be distinguished in terms of performance or further quantitative indicators which can be crosschecked by integrating a reporting mechanism. The work itself can be fixed in alignment with rules and guidelines. Furthermore, the input (skills and know-how) can be controlled by appropriate training schedules for each employee. The structure of the procedure is unaltered as long as the conditions are constant.[16]

Planning and Scheduling

Planning and scheduling are the suitable kind of coordination method for sequential structured interdependences. Plans for projects could inherit many divisional subplans and are an overreaching composed document.[1] It can serve as a guideline for processes distinguished with fixed set of rules including deliverables and expectations. However, plans with high quality takes deviations throughout the timeline into consideration with integrating adaptation mechanisms to reach operational agility.

Mutual Adjustments

Mutual adjustment as a coordination method is mostly seen in teams having complex and large interdependencies. With this being said, it is commonly used in reciprocal interdependencies where resources are exchanged, and tasks are completed parallelly. Due to the dynamic environment new intelligence unfolds during the completion of the task which needs to be transferred correctly for the other team member’s adaptation. The difficulty of handling the information flow which has typically an iterative character lays on team members working as experts in an operator role without the influence of a manager in a higher hierarchy.[15]

Limitations of the Construct

As every other theory, there have been academics who have been opposing the construct of J.D. Thompson. McCan & Galbraith[17] argue in their work that it does not seem to be adequate enough categorizing interdependences without taking their respective intensity degrees into account. The lack of quantifying the degree of an interdependence in an ordinal scale makes it difficult to coordinate certain conditions. For example, Thompson proposed that pooled interdependences are less intensive compared to a sequential one. Additionally, both pooled and sequential types indicate smaller interdependences in contrary to a reciprocal structure. Hence, this leads to the question how much more or less is the divergence of both types? Further, they have raised the question “if three pooled interdependences are smaller or larger than only one reciprocally structured interdependence”? Another interesting thought was how to differentiate the complexity levels of interdependences in an unexpected conflict situation? They have argued that certain organizational structures like pooled interdependences were much handier for having conflict situations within the team members. Would not a source of conflict generate more complexity within the operational excellence and how would this complexity effect the management control mechanisms? The vagueness of Thompson’s construct hinders the persuasiveness of his theory as an instrument for resolving contemporary organizational questions. As a counter argument McCan & Galbraith proposed a less cryptic measure in their theory by utilizing the amount of “workflow exchange” as an adaptation in determining the exact degree of interdependence.[3] They have criticized the construct of Thompson extensively based on Lewin’s definition of “construct” by highlighting the importance that a construct is a tool for solving problems. Lewin argues that fully advanced constructs must have the capability of distinguishing and comparing related interorganizational occurrences. This leads to the previously mentioned question if Thompson’s approach contains the ability of (a) examining the contrast between the effects of various quantities of interdependence in organizations as well as (b) differentiating interdependences and alternative accompanying consequences of the work force behaviours.

Annotated Bibliography

*F. Ter Chian Tan, S. L. Pan and M. Zuo, "Realising platform operational agility through information technology–enabled capabilities: A resource‐interdependence perspective," INFORMATION SYSTEMS JOURNAL, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 582-608, 2019

This paper focuses on IT compelled operational flexibility on the basis of complex resource interdependencies. It gives the reader a solid introduction to resource interdependencies and their respective management control mechanisms concentrated on IT applications. The paper backs up its statements with a real-world case study conducted in an organization located in China. Strategies to manage these complexities are assessed with the help of internal intelligence generated by the conducted interviews. Hence, it outlines the effects of IT driven coordination mechanisms on the complexity of different types of interdependencies.

*J. D. Thompson, Organizations in Action. Social Science Bases and Administrative Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967'

J.D Thompson’s book has continually been studied as a turning point in the progress of “organization theory”. It has been studied by many researchers as a solid data base and evolved into a “classic” within the organizational theory field. Many scholars tried to interpret, extend or even contraticdted with Thompson’s arguments. Besides the above mentioned interdpendence theories, it encompases a further sociolagical point of view on many organisation related topics. It can give the reader further insights on J.D.Thompson’s theories.

*J. Frost, K. Bagban and R. Vogel, "Managing Interdependence in Multi-business Organizations : A Case Study of Management Control Systems," Schmalenbach Business Review, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 225-260, 2016

To be continued..

*B. Victor and R. S. Blackburn, "Interdependence: An Alternative Conceptualization," The Academy of Management Review, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 486-498, 1987

To be continued..

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Project Management Institute, Inc., The standard for project management A Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge (pmbok® Guide) – Seventh Edition and the Standard for Project Management (english), Project Management Institute, Inc., 2021

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "F. Ter Chian Tan, S. L. Pan and M. Zuo, "Realising platform operational agility through information technology–enabled capabilities: A resource‐interdependence perspective," INFORMATION SYSTEMS JOURNAL, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 582-608, 2019

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "B. Victor and R. S. Blackburn, "Interdependence: An Alternative Conceptualization," The Academy of Management Review, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 486-498, 1987

- ↑ "R. H. Chenhall and D. Morris, "THE IMPACT OF STRUCTURE, ENVIRONMENT, AND INTERDEPENDENCE ON THE PERCEIVED USEFULNESS OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING SYSTEMS," Accounting Review, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 16-135, 1986

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 J. D. Thompson, Organizations in Action. Social Science Bases and Administrative Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

- ↑ J. R. Galbraith, Organization Design. Reading, Mass, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1977.

- ↑ S. R. Barley, "Explaining pooled interdependence with a respective example & figure," Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 1, p. 61, 1990.

- ↑ M. J. Kostecki and K. Mrela, "Book Reviews : Andrew H. Van de Ven and Diane Ferry: Measuring and Assessing Organizations," Laboratory of Organizational Sociology. The Polish Academy of Sciences, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 300-302, 1981

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 J. Frost, K. Bagban and R. Vogel, "Managing Interdependence in Multi-business Organizations : A Case Study of Management Control Systems," Schmalenbach Business Review, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 225-260, 2016

- ↑ P. Adler, "INTERDEPARTMENTAL INTERDEPENDENCE AND COORDINATION - THE CASE OF THE DESIGN/MANUFACTURING INTERFACE," Orhanization Science, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 147-167, 1995.

- ↑ B. Ambos and B. B. Schlegelmilch, "Innovation and control in the multinational firm: A comparison of political and contingency approaches," Strategic Management Journal, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 472-486, 2007

- ↑ N. Macintosh and R. Daft, "MANAGEMENT CONTROL-SYSTEMS AND DEPARTMENTAL INTERDEPENDENCIES - AN EMPIRICAL-STUDY," Accounting Organizations and Society, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 49-61, 1987

- ↑ V. Blazevic and A. Lievens, "Learning during the new financial service innovation process – antecedents and performance effects," Journal of Business Research, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 374-391, 2004.

- ↑ C. Tomkins, "Interdependencies, trust and information in relationships, alliances and networks," Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 161-191, 2001

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 H. Mintzberg, The structuring of organizations : a synthesis of the research, Prentice-Hall, 1979.

- ↑ R. Schwarz, "Harvard Business Review," Harvard Business Publishing, 23 March 2017. [Online. [Accessed 19 February 2022]]

- ↑ J. McCann and J. Galbraith, "Interdepartmental relations. In P.Nystrom & W.Starbuck (Eds)," in Handbook of Organizational Design, New York, Oxford University Press, 1981, pp. 60-84.