Front-end Sustainability: Initiating the right sustainable projects

By Kristine Fisker, Msc. Eng. Design and Innovation, Specialized in Systems Engineering and Design for Societal Transitions in agrifood

Projects shape society and our world permanently, by shaping the impact of the products, buildings, infrastructure, policies, services and systems designed within them. One of the most critical questions for project management going forward will be how to aid in tackling the large, complex, and interlinked sustainability challenges that need to be solved for societies worldwide to be sustained and prosper[1].

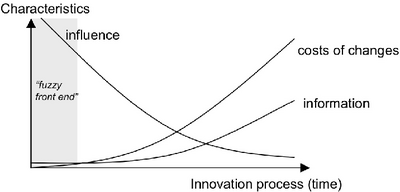

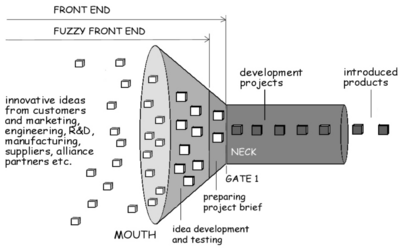

The Front-End of Innovation, or the Fuzzy Front-End refers to the phase where project ideas and concepts are searched for, defined, and evaluated for further development. Sustainability-Driven Innovation or Sustainable Innovation refers to the creation of new market space, products and services or processes driven by social, environmental or sustainability issues[2]. The Front-End of Innovation is the most critical part of projects in determining the final impact[3][4]. Even so, as sustainability impacts of projects is assigned increasing importance, the Front-End of Sustainability-Driven Innovation has received little attention by the field of project management[1][5][6]. Management principles for the Front-End of Innovation can be found in the field of design[7], but still only few descriptions of the Front-End of Sustainability-Driven Innovation.

This article will provide a high level overview of considerations and frameworks that project, program and portfolio managers can apply to transform front-end processes for increased sustainability impact of their projects, which can increase resilience and opportunity creation for their organizations. As the link between front-end innovation and sustainability is an emerging field of study, this article combines current best practices within front-end management- and sustainability management.

Contents

|

The Front-End: An Overlooked Key to Sustainable Impact

Companies that develop solutions to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can discover new growth opportunities and reduce risk to their continued operation. As governments and international organizations keep increasing efforts to deliver on the SDGs, it will strengthen the financial value of corporate sustainability, e.g. as taxes and pricing mechanisms are introduced to internalize externalities [8]. Sustainability-Driven Innovation will thus become an increasing source of competitive advantage, and mastering the front-end of environmental innovation could be crucial for business success and longevity [5].

The Front-End is the most uncertain, challenging part of projects, while at the same time being the part of the project that has the largest influence on final project impact[3][4](see Figure 1). Investing in the front-end project development is generally described as having one of the highest payback of possible investments [4]. To achieve a high level of sustainability rather than a lower level, companies must integrate sustainability considerations into the early stages of the innovation process, as this is the phase where fundamental project requirements and features are defined, and thus the final impact, that will often not be possible to be changed later[5].

Application

Advice and frameworks for managing front-end innovation and sustainability is summarized here in 4 steps of increasing complexity in the following.

1. Know to challenge initial ideas and manage the search for impactful concepts

Realizing the potential and the common pitfalls in front-end innovation management, and allocating resources to manage the front-end, is the very foundation of sustainable project impact.

In numerous projects, the initial solution idea goes unchallenged and eventually becomes the chosen project concept[1][5][9], and the common practice of today is to apply downstream analysis of a given alternative, rather than upstream evaluation of alternative concepts based on needs, goals and priorities[9]. This tendency to define projects based on a preconceived idea of solution to the problem at hand is understandable, as the front-end can otherwise seem to have too few constraints to be managed. Going with a preconcieved solution from the beginning can however be highly problematic, as the initial solution idea often is based on a large amount of assumptions, and not ideal in terms of appropriateness or impact towards the desired outcomes [10]. This is especially problematic for sustainability, as the amount of impacts and trade-offs to be considered and evaluated is even higher than in traditional projects [9]. It is suggested that companies could prevent a significant amount down-stream sustainability issues from arising, by reallocating resources towards front-end innovation, where sustainability issues can be designed out of the future portfolio[6][5].

To exemplify, it is a common strategy for the building departments of organizations to base all their sustainability projects on how to build more buildings, parking lots, etc. with minimal environmental impact, but not to consider initiating projects that map which buildings they could entirely avoid building based on e.g. increased digitization of work, or optimization of the utilization of current space. For a manager in such an organization to simply become aware of this scoping bias and encourage further solution exploration based on desired outcomes, could have a significant potential in reducing the organizations' emissions and resource consumption.

2. Create conditions for explorative Front-End Innovation

If you as a manager have been convinced of the potential value of prioritizing front-end eco-innovation, next step is to figure out how to systematically do so.

2.a Focusing on purpose, by setting priorities and goals

Focusing on purpose/benefits, prioritizing and goal setting is key to avoiding assuming solutions. Good management of priorities and goals for the organization portfolio, for programs within the portfolio, and for individual projects is commonly described as a key step to successfully achieving impact towards sustainability[8][11][2][11]. This can sound obvious, but explicitly formulating and prioritising goals is instrumental in keeping employees and external stakeholders aligned on the desired outcome, to ensure working in the same direction, to avoid excessive scope creep, and to avoid fixating on specific solution paths rather than desired outcomes.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals is one of the most recognized set of defined sustainability goals with defined indicators for each goal. The SDG Compass is a systematic guide for businesses to use the SDGs to define priorities, set goals and integrate them into operations. The SDG-compass process is summarized briefly in the wiki-article Sustainability in Project and Portfolio Management. The SDG-check for guiding open innovation is another guide with templates for using the SDGs specifically in the front-end of open innovation projects[12].

Methodologies for managing value-based priorities and goals include Requirement Management, Goal Hierachy, and Benefits Realization Management (BRM), Objectives and Key Results (OKR).

2.b Apply design competencies to manage front-end innovation

The 'fuzzy' front-end can in fact become less fuzzy, and can be flexibly managed with appropriate tools, skillets and experience. Design has become the main framework for managing innovation, and designers and design engineers are increasingly utilized for their competencies and methodologies in navigating and facilitating value-based concept exploration and the complexity and uncertainty of front-end innovation[7], increasingly also within the public sector[13]. A designer can facilitate and manage the process for teams of field-specific and environmental specialists.

2.c The Front-End Innovation Unit

Several sources suggest a small Front-End Innovation/Delivery Unit/Lab/Incubator, including McKinsey[1] and the Danish Design Center[14] and others[6]. This team should be dedicated to systematically working with the front-end, to ensure official responsibility for exploring the front-end, before project scopes are assumed, and to build front-end competencies within the organization. Because the ideal pace of front-end innovation is iterative and rapid, a smaller team is preferred. Recommendations and insights for managers of innovation units can be found in a report by the Danish Design Center "Diving deep into corporate innovation"[15].

Having a front-end sustainability unit can be considered for actively managing the implementation of development plans[1].

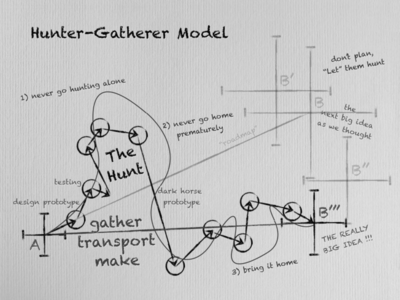

2.d Allowing flexibility

Numerous sources emphasize the importance of flexibility in early stages of front-end innovation[9][11][16]

2.e Consider the future

A common way

Front-End 'Delivery' Unit The Front-End Innovation Unit

Hunter gathering

Future forecasting

Team makeup

3. Move from a reactive to a pro-active, value-focused strategy

As sustainability is a new lense to view projects through, it requires rethinking... Move from reactive to pro-active.

"we concluded that there are three shifts that characterise the integration of sustainability and project management. Considering sustainability implies, firstly, a shift of scope in the management of projects: from managing time, budget and quality, to managing social, environmental, and economic impact. Secondly, it implies a shift of paradigm of project management: from an approach that can be characterised by predictability and controllability, to an approach that is characterised by flexibility, complexity and opportunity. And thirdly, considering sustainability implies a mind shift for the project manager: from delivering requested results, to taking responsibility for sustainable development in organisations and society."

Purpose driven.

4. Open up to external collaborative innovation

The next step to true sustainability impact of projects, programs and portfolios is working collaboratively across organizations, as the scope of the long-term, complex and systemic sustainability challenges is beyond what a single organization, government or individual can solve alone [14].

Stakeholder involvement for sustsinability

Mission Driven Innovation

Open Innovation: Going beyond the individual organization

Logical Framework LFA

OECD Mission Action Lab. Danish Design Center

Developing a Mission-driven Portfolio for Systemic Impact

The Mission Playbook by Danish Design Center. For ambitious, longterm impact across organisations. "mission managers who focus on achieving a long-term vision of change for a wide range of stakeholders instead of internal organizational development." [14]

"Creating impact means allowing room for the uncertainty that is an inevitable

part of long-term missions.

To create impact, we think less in single activities and more in portfolios. We

must consider how to involve a wider field – for instance defined by a policy

or market domain – to take part in achieving a concrete, measurable change.

And most importantly, we must also set up mechanisms that facilitate a con-

stant flow of learning from the activities we put in place, and have a manage-

ment process in place that acts on these insights."

"Missions call for a structure that balances stability and agility – predictabil- ity and unpredictability. That means creating a governance structure for the mission work that leaves room for changing the project portfolio and the ac- tor landscape as the mission progresses. The foundation for making decisions like that is to build in loops of learning at the heart of the mission in order to constantly react and adapt to new learn- ings from both within and outside the mission ecosystem. This means, the task is not “just” to build the solution, but to create the sys- tem around the solution that makes its achievement possible. Value creation, then, becomes a task of working towards committing people to the mission in order to stimulate several smaller innovations that point in the same direc- tion rather than chasing the next big bang."

"This roadmap outlined not only project proposals, but “infrastructure” activities such as communication, new partnerships and investments in new tools and capabilities. Underpin- ning this we created a systematic learning mechanism - a process of on-go- ing portfolio assessment and adjustment. This mechanism turned out to be crucial in our management of the evolution of this mission."

[14].

Limitations

"The tools required for this can perhaps be mastered more easily in big, resourceful companies, but larger companies may have difficulties in allowing the eco-innovation process to be open, informal and creative, aspects which contributed positively to the success of novel eco- innovations." ([5])

Larger than any one organization - benefits beyond the individual organization.

Balancing challenging and maintaining the established

Innovation managers in the front-end of Innovation report that balancing between challenging and maintaining the established is one of the grearest challenges in their work. In general, figuring out when to continue business-as-usual, doing incremental innovation, and when to change the organisations' focus and competencies to stay competitive and relevant, is a though challenge for businesses. Especially in large organisations, that take longer to change and adapt, there can be a tendency to push-out radial innovations. As examples, x invented the digital camera, x invented the labtop, but it was startups that ended up succesfully adapting to the technology. It will be challenging for businesses that have built up their infrastructures and skillsets around fundamentally unsustainable business opportunities to embrace the opportunity of increasing pressures to transition.

Another limitation is the still lacking incentive structures for ambitious sustainability innovation projects aiming at benefits that go beyond the individual organisation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Morris, Peter W. G. 2017. Climate Change and What the Project Management Profession Should Be Doing about It - a UK Perspective. APM, UCL.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Stock, Tim, Michael Obenaus, Amara Slaymaker, and Günther Seliger, 2017. A Model for the Development of Sustainable Innovations for the Early Phase of the Innovation Process, Procedia Manufacturing 8:215–22. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351978917300331?via%3Dihub

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Figueiredo, João, N. Correia, I. Ruivo, and J. L. Alves. 2015. “A Cross-Functional Approach for the Fuzzy Front End: Highlights From a Conceptual Project.” in International Conference on Engineering Design ICED15. Milan, Italy. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-CROSS-FUNCTIONAL-APPROACH-FOR-THE-FUZZY-FRONT-A-Figueiredo-Correia/717996dc452bfc56468287064373c468d8de282b)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Dewulf, Kristel. 2013. "Sustainable Product Innovation: The Importance of the Front-End Stage in the Innovation Process." in Advances in Industrial Design Engineering. IntechOpen.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Bocken, N. M. P., M. Farracho, R. Bosworth, and R. Kemp, 2014. The Front-End of Eco-Innovation for Eco-Innovative Small and Medium Sized Companies, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 31:43–57. Available at: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/245338/The-front-end-of-eco-innovation_final__open-access.pdf?sequence=1 )

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Sherwin, Chris, 2017. The Fuzzy Front-End of Sustainability, Edie. (https://www.edie.net/the-fuzzy-front-end-of-sustainability/) )

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hernández, Ricardo J., Rachel Cooper, Bruce Tether, and Emma Murphy. 2018. “Design, the Language of Innovation: A Review of the Design Studies Literature.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 4(3):249–74.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 United Nations, FRI, and wbcsd. n.d. “SDG Compass - The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs (https://sdgcompass.org/).”

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Olsson, Nils O. E., and Knut Samset. 2006. “Front-End Project Management, Flexibility, and Project Success.” in PMI® Research Conference: New Directions in Project Management, Montréal, Québec, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Cross, Nigel. 2000. Engineering Design Methods: Strategies for Product Design. 4th ed. John Wiley And Sons Ltd.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Green Project Management GPM. 2019. “P5TM Standard for Sustainability in Project Management Version 2.0.”

- ↑ Von Geibler, Justus, Julius Piwowar, and Annika Greven. 2019. “The Sdg-Check: Guiding Open Innovation towards Sustainable Development Goals.” Technology Innovation Management Review 9(3):20–37. Available at: https://timreview.ca/article/1222.

- ↑ Bason, Christian. 2021. “The Diversity of Design Toolkits in the Public Sector.” OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation. Retrieved May 4, 2023 (https://oecd-opsi.org/blog/the-diversity-of-design-toolkits-in-the-public-sector/).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Bason, Christian. 2023. “Embracing a New Leadership Role for the Future: Mission Managers.” Danish Design Center. Retrieved May 3, 2023 (https://ddc.dk/mission-managers/)

- ↑ Danish Design Center. 2021. Diving Deep into Corporate Innovation. Copenhagen. Available at: https://ddc.dk/analysis-diving-deep-into-corporate-innovation/

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Steinert, Martin, and Larry John Leifer. 2012. “‘Finding One’s Way’: Re-Discovering a Hunter-Gatherer Model Based on Wayfaring.” International Journal of Engineering Education 28(2).