Organisational resilience with mindfulness

Contents |

Abstract

An increasing demand for resilience within sociotechnical organisations has led to several managerial concepts preparing organisations for unexpected events. Thorough management is crucial in resilient organisations (check ref, Geraldi et al, 2009) and mindfulness encompass the risk of the human mind. Mindful project managers are aware of cognitive biases and irrationalities. They inspire workers to be rational and fact-based.

Mindfulness is about keeping a high level of alertness and awareness of context and using awareness in our decision and actions [1]. This article will address how mindfulness is used as an managerial instrument to obtain resilience in an organisation. The article will define the mindfulness theory with description of the 5 principles. Furthermore complex organisations and unexpected events related to unknown/unknowns is defined. There will be a focus on “commitment to resilience” and “deference to expertise” which focusing on reacting to unexpected events hence improving the resilience in the organisation.

Big idea /Overview

Mindfulness is a term introduced by the professors Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe after studying high reliability organizations (HRO). These organizations have no choice but to function reliable. Weick and Sutcliffe [2] found that reliability does not mean a complete lack of variation. It is just the opposite. It takes mindful variety to assure stable high performance. The learnings and techniques from the HRO’s can be implemented in projects and in organizations who want a higher reliability.

In brief, mindfulness involves the ability to detect important aspects of the context and take timely, appropriate action. A well-developed capability for mindfulness catches the unexpected earlier when it is smaller, comprehends its potential importance despite the small size of the disruption, and removes, contains or rebounds from the effects of the unexpected. Managing the unexpected, mindfully project managers and organizations are able to deliver reliably the task they were asked to do.

The expectations of individuals tend not to correspond with the reality. We are all affected by cognitive biases and the mindful project manager is aware of that.

Mindfulness VS Mindlessness

To underline the importance of mindfulness its counterpart mindlessness is described. Mindlessness is characterized by at style of mental functioning in which people follow recipes, impose old categories to classify what they see, act with some rigidity, operate on automatic pilot, and mislabel unfamiliar new contexts as familiar old ones (Weick and Sutcliffe).

Application

An increasing demand for resilience within sociotechnical systems has led to several managerial concepts preparing organisations and their project, program and portfolio managers for unexpected events. The awareness of resilience and antifragility is crucial for HRO’s, but all organisations can learn from the mind-set of the HRO’s. Even organisations without risks of casualties can improve their practises with mindfulness. It is a matter of context. Once the context, the precautions, the assumptions, the focus of attention, and what was ignored, it becomes obvious that many organizations are just as exposed to the unexpected as HRO’s and just as much in need of mindfulness. E.g an unexpected shutdown at an assembly line is not a severe crisis. However the supervisor did not expect any fails or shutdowns. To him it is an unexpected crisis. Unexpected events occur at all organizational levels.

Project, Program and Portfolio managers are familiar with many project management tools and they are able to define project time, costs, risks, stakeholders etc. by PMI standards. However, when projects become more complex e.g. in order of technical and organisational complexity, social intricacy of human behaviour or uncertainty of long lifecycles, standard tools becomes inadequate. We tend to think of ourselves as rational beings, but in fact subconscious processes often drive human behaviour [EXAMPLE]. Not being aware of these subconscious thought processes can adversely affect projects. Mindful project managers know that they do not know everything. They know that their thoughts and impressions are affected by cognitive biases. Thus, they must be aware of their irrationalities to act in a mindful manner and become rational and fact-based. Mindfulness is instrumental in managing the intersection between human behaviour and uncertainties thus generating processes within projects, programs and portfolios that are more reliable.

Principles

Weick and Sutcliffe[2] have developed five principles that harness the key characteristics in mindfulness. These guidelines/principles apply upward to divisions and organizations as well as downward to teams, crews and team leaders. The principles can be adopted by anyone. Each principle is given an example from different HRO’s.

| Principle | Description | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Preoccupation with failure | A preoccupation with failure focuses the organization to convert small errors and failures into organizational learnings and improvements.

“Pay close attention to weak signals of failure that may be symptoms of larger problems within the system” [2] Be wary of the potential liabilities of successes such as complacency, the temptation to reduce margins of safety and drift into automatic processes. |

The airline industry encourage their personnel to report all failures and near misses generating failure catalogs. A big effort is expended in reviewing all reports to improve processes and workarounds. |

| Reluctance to simplify | Simplify mindfully and reluctantly. Have in mind that simplification can become too simple resulting in useless, unprecise simplifications e.g. explanations and categories. Problems faced in complex projects typically offer several options and a nuanced picture to fully understand the best solution. | A merger of two North American railroad companies in 1996 resulted in a gridlock of the system from North Platte, Nebraska to Chicago. Many small errors and failures occurred after the merger, but the most obvious reason for the gridlock was an ignorant and arrogant attitude toward innovative and complex solutions. The top management insisted that trains are made up in central locations called classification yards, not in dispersed locations called shipper yards, satellite yards or mainline tracks. Freight shipped by railroaders are shipped by rail, not barge. In this case the problems caused by these simplifications were overlooked until the central location or excessive grain shipments became a bottleneck causing the gridlock. |

| Sensitivity to operations | An organization must have an integrated overall and aligned picture of operation. Sensitivity to operations is closely related to sensitivity to relationships. Meaning a clear and unprejudiced communication between operation and management is crucial to understand the big picture.

Furthermore, it is important to be responsive to the changing reality of projects. This can be obtained first by controlling the progress, monitor deviations and implication on projects, and second being mindful to potential unexpected events. |

1: Studies of nuclear weapons suggest that many problems arise not from a single failure, but when small deviations in different operational areas combine to create conditions that were never imagined in the plans and designs[3]

2: The microcomputer industry can be characterized as a high velocity environment with a rapid and discontinuous change in demand, competitors, technology and inaccurate, unavailable or obsolete information. Decision-makers deal with this environment by paying close attention to real-time information e.g. concerning current operations or environments. |

| Commitment to resilience | Accommodate unexpected events and react to them quickly as they arise.

Resilience involves (a) the ability to absorb strain and preserve the functioning of the project; (b) ability to recover quickly; (c) ability to learn from the unexpected event and how it impacted the project.[1] |

In the North American railroad merger case the meltdown of operations showed an inability to bounce back when the initial problems occurred. The railroad were short of men right after the merger and they trimmed crews, locomotives and supervisors shortly before the gridlock from Nebraska to Chicago. Slack resources is a common way to create resilience. |

| Deference to expertise (Collective mindfulness) | Deference to expertise is about involving experts in the decision-making. The experts actively involved in the projects are more capable to give articulate solutions to problems. Rigid hierarchies have their own special vulnerability to error where errors at high levels tend to pick up and combine errors at low levels. HRO’s push decision making down and around where decision is made on the front line. The authority migrate to the people with the most expertise, regardless of their rank.

Collective mindfulness is associated with cultures and structures that promote open discussions of errors, mistakes and awareness. |

In the North American railroad merger case the decisions were made from top management even though their operational expertise were outdated. Furthermore the management were only fed with information that they wanted to hear. A horrible paradigm where management were fed with biased information and insisted to make decisions at top level. This classic command-and-control bureaucracy is adequate for a stable situation but too inflexible in times of change.

(eventually Carlsberg case) |

Topics in Mindfulness

[The five principles are general guidelines of mindfulness. To be able to implement mindfulness as a manager you must be aware of your cognitive behaviour as a human including how you experience the world. Weick and Sutcliffe [2] [4] (reference 2001 & 2007) It is recognised that you start Write about circle of influence from IDA event…... Continuous learning] FINISH WRITING

Expectations

An expectation is to envision something, that is reasonably certain to come true. To expect something is to be mentally ready for it. “ Expectations form the basis for virtually all deliberate action because expectancies about how the world operates serve as implicit assumptions that guide behavioural choices” [5]. With that in mind, it is important to be mindful about your expectations. Expectations direct your attention to certain features or events, which means that they affect what you notice and remember. Whenever our expectations does not match with reality our mind adjust you expectations to reality. It can be compared with a hypothesis-test [Wikilink]. The human mind search for confirmation of its expectations but is biased to avoid looking for evidence that disconfirm them. HRO’s work hard to counteract this tendency. They routinely suspect their expectations for being incomplete. With this process, they check if the normal accepted expectation still pass the hypothesis test.

The capability for mindfulness (Categories)

Whenever people change the way they perceive the world they essentially rework the way they label and categorize what they see. This change in perception can be described with the following process:

- Re-examine discarded information

- Monitor how categories affect expectations and,

- Remove dated distinctions

Firstly, to rework one’s categories mindfully implies to evaluate how much information is discarded with a categorisation of an instance with similar characteristics. Generally categorization help gaining control in a fast pace world. They can predict what will happen and plan one’s own actions. Without categories, any person or situation would be unique and therefore conserve scarce mental resources of attention and thinking. To exemplify categorization a university professor meet hundreds of students each day and have to categorize different types of students. The professor could categorize the students into categories such as active/passive, introvert/extrovert, Intelligent/less intelligent, man/women, young/old etc. The categories guide the professor how (s)he should behave or treat the different students. One category cannot describe all facets of a person and the professor must be aware of the discarded information within each category. Secondly, mindful reworking of categories also mean that one pay close attention to their effect on the expectations. Categories and expectations are closely related. E.g., a person categorised as an expert is expected to know the answers within his/her field of expertise. These expectations constantly have to be revised and evaluated. It may be necessary to differentiate the expectations, replace them, supplement them, or discard the whole category. Third, mindful reworking means a check whether the categories remain plausible. Outdated categorisation with implausible distinctions of expectations ensure trouble. This is the basic misreading in HRO’s. The trouble starts when you fail to notice that you only look for whatever confirms your categories and expectations. “Believing is seeing. You see what you expect to see. You see what you have the labels to see. You see what you have the skills to manage.” (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001) People who persistently rework their categories and refine them, differentiate them, update them, and replace them notice more and catch unexpected events earlier in their development. That is the essence of mindfulness (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001).

The Unexpected

Unexpected events can be categorised in three forms (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007): The unexpected occur when an event that was

- expected to happen fail to occur.

- not expected to happen does happen.

- simply unthought-of happens (Unknown/unkowns)

Unexpected events are caused by faulty expectations and the fact that we sought to look for evidence that confirm our expectations. These confirmations are found to boost our experience of being in control. However, this confirming behaviour has adverse effect on how quick we realise we are wrong and rework our expectations. A slow realisation time allows problems to worsen and become harder to solve and they might even be entangled with other problems. HRO’s strive to minimize the risk of events unthought-of happens by steering people towards mindful practices that encourage imagination. People inadvertently trivialize the importance of imagination. Instead people tend to “Expect the unexpected” to maintain their desire for control and predictability.

Putting Mindfulness into Practive as a Project, Program and Portfolio Manager

Putting Mindfulness into practice as a Project, Program and Portfolio Manager Weick and Sutcliffe(reference) have developed concrete processes based on the five principles and on practices identified in the best HRO’s. The processes is organised under the headings of “Awareness and Anticipation of the Unexpected” and “Containment of those unexpected events that occur” Enhancing awareness and anticipation

INSERT PROCESSES

Limitations

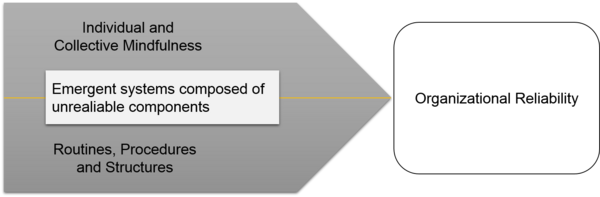

Weick and Sutcliffe argue that human cognition in the mindfulness theory is the solution to reliability problems, but they tend to over-simplify the resilience concept by neglecting the importance of routine-based reliability. Studies of human systems reveal two strategies for achieving reliable performance (Butler & Gray, 2006):

- Routine-based reliability

- Mindfulness-based reliability

Organizationally, routine-based reliability involves the creation and execution of standard operating and decision-making procedures, which may be unique to the organization or widely accepted across an industry (Spender, 1989). The routine-based reliability strategy rely on predefined procedures, routines and training designed to decrease cognitive human problem solving, to reduce errors, unwanted variation and waste. Defining procedures etc. is a frontloaded(Front end thinking) process where unknown/unknowns[link] may oppose a major risk because unexpected events cannot be implemented into the procedures. While routine-based approaches focus on reducing or eliminating situated human cognition as the cause of errors, mindfulness-based approaches focus on promoting highly situated human cognition as the solution to individual and organisational reliability problems (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2001). Mindfulness focus on one of the two strategies and ignore or assume that optimal routines, procedures and structures are in place. Mindfulness does not describe the interdependencies and synergistic impacts between the two strategies.

Mindfulness is a complex management theory. As the principle “Relucatance to simplify” justify, it takes a complex idea to capture a complex phenomenon. To fully implement mindfulness and deal with the unexpected it is required to organise in a complex manner. Likewise mindfulness preach a need for complex set of ideas to understand what people are doing and why it works thus requiring workers with a certain level of receptivity and resources.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Oehmen, J. et al. 2015. Complexity Management for Projects, Programmes, and Portfolios: An Engineering Systems Perspective. Copenhagen: PMI

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Weick, K. E. and Sutcliffe, K. M. 2001. Managing the unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0787956279

- ↑ Sagan S.D. 1993. The limits of safety: Organizations Accidents and Nuclear Weapons. Princeton, NJ. Princeton University.

- ↑ Weick, K. E. and Sutcliffe, K. M. 2007. Managing the unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 9780787996499

- ↑ Olson, J. M., Roese, J. M. and Zanna, M. P. Expectancies. In Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles, edited by E.T. Higgins & A.W. Kruglanski, pp211-238. New York, NY: Guilford.

Further Reading

Human cognition (further reading) Mindfulness UN: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_Pacific_Railroad Systems reliability Reliability