Managing Projects with Earned Value Management

The management of technical projects has become a real challenge in an always more competitive market where effective project Planning and Control approaches need to comply with clients’ requirements. For successfully completing a project, this needs to both meet the technical objectives and be completed on schedule and within budget. This task involves comparing the actual situation with the planned one in terms of Scope, Time and Costs, which, together, form the Project Management Triangle. To guarantee that all project deliverables are achieved, it is very important that all three dimensions of project performance are monitored and controlled.

However, if any of these dimension is analyzed without taking into account the other two, problems may arise, because only a partial overview of the project status would be provided. For instance, a project may be on budget whilst having accomplished less work than what was planned to be accomplished. On the other hand, a project may also be on budget while having accomplished more work than what was planned. In the first case the project is said to be behind schedule, while in the second case it would be ahead of schedule. How can time measurements be related to costs? And how can managers have an objective overview of the current state of their projects? To answer these questions an effective project control system should be created, to provide managers with timely and accurate information on deviations of costs and time measurements from the objectives established during the planning phase of the project.

This is where Earned Value Management (EVM) come into play by allowing for both schedule and cost analysis against the physical amount of work accomplished. Earned Value Management is a project management technique used for measuring, at any time, the progress and the integrated performance of a project in an objective way. It is an approach that effectively combines the scope of a project with time and costs parameters and allows alerting to deviations from budget and schedule baseline. In this way it can generate early warning signals to detect problems or to exploit new opportunities within the project.

With this methodology it is possible not only to see how a project is performing, but to predict future performance as well. In fact, it is also able to estimate the project completion date and final cost and to provide accurate forecasts of performance problems, which can be a fundamental contribution when managing a project.

Today, Earned Value Management is considered one of the most powerful techniques used in the management of complex projects in commercial, government or private environments. The purpose of this article is to provide the reader with a brief but effective guidance to the concept of EVM and to its application.

Contents |

Background and purpose

Earned Value Management, formerly known as Earned Value, emerged in its embryonic version in the 1960’s as a financial analysis discipline in US Government programs. It was the creation of an Industrial Engineer, named A. Ernest Fitzgerald, whose field of expertise was work measurement.

At that time the latest Project Management tool was the Project Evaluation and Review technique (PERT), which was extremely difficult to implement in an efficient manner because of the limited computing technology available at the time [1]. As a consequence, it was not always reliable and timely and therefore not widely used[1] . The computing problems became even bigger[2] when a joint Navy/Stanford team decided to include resources in the PERT by adding Cost information, and introducing the PERT/Cost. Another weakness of the PERT/Cost, in the eyes of Ernest Fitzgerald, was that it adopted updated estimates as the performance measurement baseline. In order to address this and other issues related to performance measurements, Fitzgerald founded a consulting firm called Performance Management Corporations (PMC), which delivered, as one of its first products, the highly influential Earned Value Summary Guide, where a first definition of Earned Value was provided:

“Earned Value is a concept – the concept that an estimated value can be placed on all work to be performed, and once that work is accomplished that same estimated value can be considered to be “earned.” The utility of this concept as a management tool is that the summation of all earned values for work accomplished when compared to what was actually expended to perform the effort can provide management with a comprehensible, objective indicator of how the total effort or any identifiable segment is progressing.” (as cited in Morin, James B. (2016)[1]).

Shortly afterwards, Earned Value started being introduced and validated in the Ballistic System Division with its implementation in the Air Force’s Minuteman Program. Earned Value won the battle against the PERT/Cost methodology, which was concurrently proposed to the Air Force as a valid alternative. The determining criteria for sticking with Earned Value relied on the inflexibility of its basis for measurements, which in the case of PERT/Cost could be adjusted to hide overruns. On the other hand Earned value uses a non-flexible baseline. The PERT/Cost methodology encountered the Air Force rejection [3] and by mid-1960's it was decided that the Minuteman Earned Value approach would be the Air Force standard. Soon Earned Value was expanded to a Department of Defense-wide requirement.

This brief history shows how although performance measurement is the critical structural component of Earned Value, this approach was not created for that purpose only. In fact, in 1965 Estimates at Completion (EAC’s) i.e. the expected costs of a project at the date of its completion, were extremely inaccurate and finding a solution to that problem was the number one objective of Earned Value and the reason why the Air Force and Department of Defence decided to support it.

Theory of Earned Value Management

The concept

The process of controlling is fundamental to the success or failure of any project. Therefore, it is likewise important to measure the project performance throughout the whole life of the project in order for managers to take corrective actions should the project be in danger. Earned Value Management (EVM) is a project management technique used to control the time and cost performance of a project. Its core concept is "Earned value", which means the value assigned to work which has been accomplished at a certain time. By comparing this monetary value to the planned budget and to the actual cost to that work, EVM is able to measure and evaluate the status of a project at any given point in time. The specific metrics used in EVM can act as early warning signals to timely spot problems or to exploit new project opportunities.

A simple example

DTU is going through an architectural renovation project which involves, among other activities, replacing every outdoor dining table of the campus with new ones. A team has been assigned to this task and the plan is the following:

- 15 batches of 10 tables (150 tables in total) need to be installed

- It is planned to install 3 batches per day (30 tables)

- The budgeted cost per table is 200 dkk. (total budget = 30,000 dkk)

After the first day:

- 25 tables have been installed against the 30 which were planned. (The drill broke down and caused delays).

- The Total Cost for the day was 6,800 dkk. This is because a new drill has been rented and costs 1,800 dkk per day.

Basic EVM calculations for the first day:

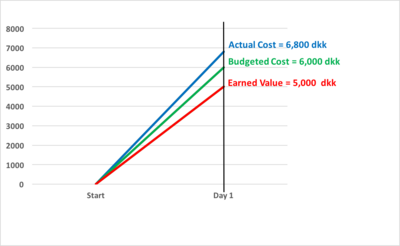

- Budgeted Cost (BC): 30 tables planned * 200 dkk/table planned = 6,000 dkk

- Earned Value (EV): 25 tables installed * 200 dkk/table installed = 5,000 dkk

- Actual cost (AC): 25 tables installed * 200 dkk/table installed + 1,800 dkk for the machine = 6,800 dkk

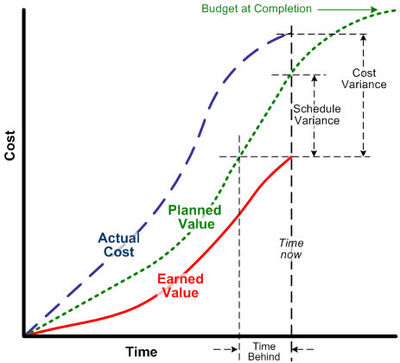

A visual representation of these three parameters is shown in Figure 2, which clearly shows that there is a difference between what it was planned and what has been accomplished. This difference regards both Cost and Schedule:

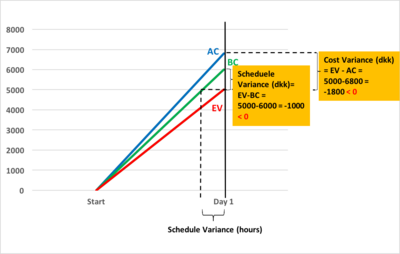

- On a Cost level the difference between Earned Value and Actual Cost is called Cost Variance and in the example is equal to: 5000 - 6800 = -1800

- It is a negative value, which means that the project is, at Day 1, over budget.

- On a Schedule level the difference between Earned Value and Budgeted Cost is called Schedule Variance and for this case is equeal to: 5000 - 6000 = -1000

- Again, the value is negative, which means that the project is, at Day 1, behind schedule.

A visual representation of the variances is provided in Figure 3

If no action is taken to modify the current performance of the project, its final state can easily be plotted by extending the Actual Cost into the future. This let us calculate the Estimate at Completion, which is the Actual Cost of the project at the time of its completion. By comparing it to the Budget at Completion, the Project Slip and the Cost Overrun of the entire project can also be calculated.

The example above represents a very simple situation for evaluating the progress of a single task. In reality it is usually significantly more difficult to determine the realistic progress of a project. However, this is an essential prerequisite to ensure the accuracy and meaningfulness of the Earned Value Management methodology.

EVM Terminology

In the previous section a few technical terms of EVM have been briefly introduced. These are extremely important since Earned Value Management uses a specific terminology which needs to be known and fully understood by all the people involved in the application of this methodology. This section presents and discuss the EVM key terms by dividing them three categories:

- The three basic metrics - to show the difference between plan, cost and progress.

- The project performance metrics - to evaluate the current project performance, in terms of costs and time.

- The project forecasting metrics - to estimate the project duration and total cost, given the current performance.

The three basic metrics

The three key parameters of EVM are the Planned Value (PV), the Earned Value (EV) and Actual Costs (AC). By calculating EV and AC during a project and by comparing it with PV a manager can draw conclusions on the performance of a project. The definitions of these fundamental metrics are given in Table 1.

| Earned Value Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Value (PV) | Formerly known as Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS).

It represents the planned project expenditures i.e. the approved budget for the work scheduled from the project start until the present time. This is established at the time the project was initially planned and represents the original intent of the project team. In the example above it is referred to as "Budgeted Cost". The total Planned Value of a project (or task) is equal to the project's (or task’s) Budget At Completion (BAC), i.e the total amount of money budgeted for the project/task. | ||||

| Earned Value (EV) | Formerly known as the Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP).

It is the percent of the approved budget actually completed at a point in time. EV is calculated by multiplying the budget for an activity by the percent progress for that activity. | ||||

| Actual Cost (AC) | Formerly known as the Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP).

It is the actual project expenditures at the present time. It includes all the costs related to the work that has been accomplished until the present instant in time. | ||||

Project Performance

The Earned Value methodology is based on monitoring these three basic metrics over the life of the project. Through some basic calculations they provide important information on how the project is doing. This information is expressed in the form of other metrics (or indicators) which are divided into two sub-categories:

- Variances, presented in Table 2;

- Indices, presented in Table 3.

| Earned Value Variances | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Variance (CV) | The difference between Earned Value and Actual Cost.

The Cost Variance shows whether and to what extent the project is under or over budget. |

| |||

| Schedule Variance (SV) | The difference between Earned Value and Planned Value.

The Schedule Variance shows whether and to what extent the project is ahead of or behind the approved schedule. |

| |||

| Earned Value Indices | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

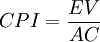

| Cost Performance Index (CPI) | The ratio between Earned Value and Actual Cost.

It is an indicator of the project cost efficiency. |

| |||

| Schedule Performance Index (SPI) | The ratio between Earned Value and Planned Value. |

| |||

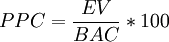

| Project Percent Complete (PPC) | Percent of project work complete.

It is the ratio between Earned Value and Budget at Completion, expressed as a percentage. |

| |||

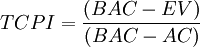

| To Complete Performance Index (TCPI) | It represents the efficiency required to complete the project on budget. It is the ratio between the planned cost of work that still needs to be complete and the amount of money remaining. |

| |||

Four Performance Scenarios

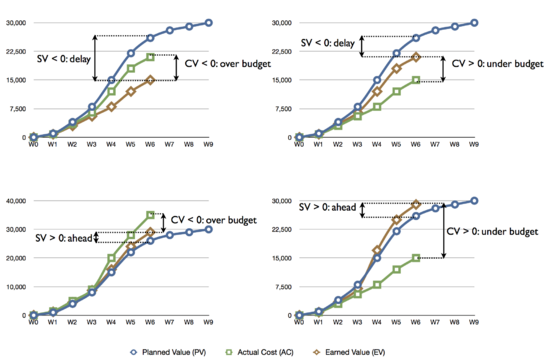

Given the cost and time dimensions and their possible variances (zero, positive or negative), nine different project performance situations can occur.

- Scenario 1: on time project, over budget,

- Scenario 2: on time project, on budget,

- Scenario 3: on time project, under budget,

- Scenario 4: early project, over budget

- Scenario 5: early project, on budget

- Scenario 6: early project, under budget

- Scenario 7: late project, over budget

- Scenario 8: late project, on budget

- Scenario 9: late project, under budget

By excluding the “on time” and/or “on budget” situations, four scenarios (4, 6, 7 and 9) are left. They are visually represented in Figure 5 using an example of a project with a planned duration of 9 weeks and the actual time equal to week 6.

Figure 5 shows the three EVM key parameters and the SV and CV under the four remaining scenarios. Depending on the SV values, the project is late or early, while The CV values determine whether the project is under or over budget.

---

Project Forecasting

| Earned Value Forecasts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

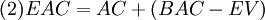

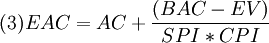

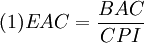

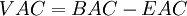

| Estimate at completion (EAC) | The estimated total cost at project completion.

As the project advances there might be unexpected events, delays and circumstances that may cause variations between the actual final cost and the planned final cost (BAC). EAC is a way to estimate/project the planned cost at the end of the project, based on the data available at a certain time. Depending on the information available and the contingency of the situation, three different formulas can be used to calculate the EAC: (1) used when it is believed that the project will keep spending at the same rate from now onwards, for example because of reasons that are likely to continue. (2) used when it is believed that the project's future expenditure will go on at the original planned amount, for example because of unexpected events that are not likely to happen again. (3) used when it is believed that both cost and schedule performance at a certain time will affect the future cost performance. |

| |||

| Variance at completion (VAC) | The variance at the completion of the project, i.e. the difference between the new estimate at completion and the planned total cost at the project´s completion.

If we forecasted that the project will be over budget, then the VAC will take up a negative value. If we forecasted that the project will be under budget, then the VAC will take up a positive value. |

| |||

Application of Earned Value Management

How to implement Earned Value Management

In order for a company to effectively apply EVM there are a series of steps that need to be carried out. These were gathered by Fleming (1998) [3] in ten "must-do's" that build up an application framework valid for projects of any size, in any industry:

- Define the Scope of Work. The foundation of EVM lies is defining the work scope of the project by deconstructing its Statement of Work (SOW) into discrete components, which will build up the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) .

- Define a bottom-up plan. All the critical processes, such as the work scope definition, scheduling and estimating resources have to be integrated into into an integrated plan of detailed cells named Control Account Plans (CAPs). The real performance measurements will take place within each CAPs and the total project’s performance will be the summation of the single CAPs' performance. Every CAP can be considered as a subproject of the main project.

- Formally schedule CAPs. Each of the defined CAPs needs to be planned and scheduled with a formal scheduling system. In earned value terms, this scheduled work represents the planned value of the project. The outcome of this step is the project master schedule, which constitutes the project manager’s defined planned value for everyone to follow.

- Assign each CAP to an executive for performance. Assigning every CAP to a functional executive for performance effectively commits that person to oversee the performance of each CAP. It is argued by Fleming (1998)[3] that companies should assign a senior functional person to each CAP, rather than a functional employee. By doing so, a strong commitment from the functional executives will be ensured.

- Define a baseline that summaries CAPs. The total project performance measurement baseline must be defined, based on the summation of the CAPs' baselines.

- Measure performance against schedule. The schedule performance of the project must be periodically measured against its planned master project schedule, in order to compute the difference between the work that has been scheduled and the work accomplished (schedule variance). At this point the behind-schedule tasks are assessed, regarding their criticality to the project. If a late task is on the critical path, or if a task involves a high risk, actions can be taken to get the late task back on schedule.

- Measure the cost efficiency against the costs incurred. The project’s performance efficiency rate needs to be periodically measured, in terms of difference between the value of work performed and the costs incurred to accomplish the work provides the cost-efficiency factor (cost variance).

- Forecast the final costs based on performance. The final cost of the project needs to be periodically forecasted based on its performance against the plan. Here is when EAC's are calculated

- Manage the remaining work. The results achieved at a certain time in a project, no matter if good or bad, are “sunk costs”, gone forever. Therefore, any improvements in performance must derive from future work. It is thus fundamental to quantify the value of the work that still needs to be completed to stay within the objectives set.

- Manage changes in baseline. Any performance baseline becomes invalid if it does not incorporate changes that may have occurred over the project's duration. Therefore, the baseline must be adapted to changes and updated.

Areas of application

EVM has proved to be a valuable methodology in many different domain and for projects of any degree of complexity. Therefore, it should be considered as a valid project management approach every time organisations could benefit from receiving early warning cost signals, able to modify the ultimate direction of project.

Some of the areas where EVM can be used are:

- Construction

- Software development

- Software projects seem to particularly benefit from the application of a simple EVM approach.

- ...

Limitations

- EVM makes use of a wide and not-so-intuitive vocabulary, which might be an obstacle when it comes to communicate the information both within the team involved in the EVM and people outside the team, including other managers in the company and/or other stakeholders.

- It requires data which might be difficult to collect i.e. real-time and accurate information from the people directly involved with the works. This could directly affect the quality of the EVM parameters.

- For instance, a CPI higher than 1.0 suggests that an under-run of costs is occurring. However, this condition could simply be due to lagging costs, slow to be registered in the organizational cost ledger. A reason for this could be that some activities of the project may be outsourced and therefore, there might be a time mismatch between the earned value measured "on spot", and the actual payment of the outsourced labor invoices, which, according generally takes more time than the recording of labor[4].

- Although it takes into account Cost, Schedule and Scope of Work, Earned Value Management does not assess the Quality dimension of the Project Management Triangle.

- It is not a stand-alone tool: EVM is not sufficient ‘per se’ to monitor projects and programs. Therefore, it must be combined with other methods.

An extension to Earned Value Management

Earned Value Management is a powerful management system, able to integrate cost, schedule, and technical performance but as mentioned above it also has some shortcomings. A peculiarity of EVM is that at the conclusion of a project which is behind schedule, the Schedule Variance (SV) is equal to zero and the Schedule Performance Index (SPI) is equal to one. Therefore, a project that was completed late, according to Earned Value metrics, seems to have a perfect schedule performance. To solve this ambiguity an extension of EVM, called Earned Schedule was introduced in 2003. Earned Schedule (ES) is an innovative analytical technique that finds a solution to the EVM dilemma by using time-based performance indicators against the cost-based indicators used by EVM. It directly derives from EVM and it does not require any additional data in order to be implemented.

See also

Annotated Bibliography

List and short description of the main references used to sustain this wiki article:

- Morin, James B. (2016). How it all began: the creation of Earned Value and the evolution of C/SPCS and C/SCSC. The Measurable News. 15-17. [1]

- A paper that documents the origins of today’s Earned Value Management methodology and describes how and why the Earned Value concept was created in the US back in the 60’s. It provides the reader with a good overview of the context in which Earned Value started being used and it describes how it was developed and accepted as a powerful Project/Program Management tool within the US Air Force’s Minuteman Ballistic Missile system and the Department of Defence.

- EVMS Education Center (2012) Basics concepts of Earned Value Management (EVM). Retrieved from https://www.humphreys-assoc.com/evms/basic-concepts-earned-value-management-evm-ta-a-74-t-1_11.html

- The article represents an introduction to the basics of Earned Value Management, which cover the all the steps from the initial project planning phase until the execution of the plan, going through techniques of data analysis and baseline adjustments. It refers to the Standard for EVMS and addresses the benefit that this methodology can bring to both contractors and customers.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Morin, James B. (2016). How it all began: the creation of Earned Value and the evolution of C/SPCS and C/SCSC. The Measurable News. Page 15-17.

- ↑ Fleming, Quentin W. and Koppelman, Joel M. (2005) Earned Value Project Management, Third Edition, Project Management Institute. Page 28.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fleming, Quentin W. and Koppelman, Joel M. (1998) Earned Value Project Management. A Powerful Tool for Software Projects. Primavera Systems, Inc. CROSSTALK The Journal of Defense Software Engineer. Page 20.

- ↑ Quentin W. Fleming and Joel M. Koppelman, Primavera Systems, Inc. (2016) The two most useful earned value metrics: the CPI and the TCPI. The Measurable News. Page 23-25.