The iron triangle as an analytical tool

Contents |

Abstract

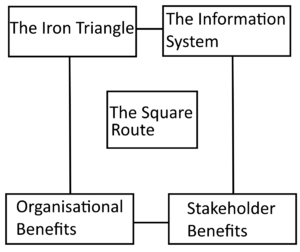

This article aims to present the Iron Triangle (also known as Project Management Triangle, Project Triangle, and Triple Constraint Triangle) as an analytical tool with a focus on Project Management through the perspective of Purpose. The Iron Triangle is considered as one of the most fundamental project management models regarding success and is based on the interrelationships between key project performance metrics, which in this case are defined as constraints. With its origins from the 1950’s, the Iron Triangle was originally applied to settle on initial project estimates and thereby evaluating the project success regarding if these estimates were met. However, this article is going to present some of the most concurrent criticisms and limitations of the classic Iron Triangle, and how key research spanning many years and crossing various industries have let to the mitigations of these issues. This has let the enhancement of the approach of the Iron Triangle into an analytical tool with the purpose of not only defining project frameworks but also to continuously assess project performance throughout its lifespan by guiding project managers to where adjustments in project constraints must be made in the case of changes in other constraints.

With regards to the application of the tool, it is first presented how each constraint application take place in at least two points of PMI’s Project Management Body of Knowledge’s processes; planning and controlling, and how PRINCE2 handles these applications. Then, practical, and strategic approaches to the balancing of the triple constraints will be presented through the Iron Triangle’s core concept of project tradeoffs. Lastly, it will be discussed how project managers can leverage the Iron Triangle from representing a set of pre-defined specifications (classic view of projects) to an analytical tool focusing on value creation (state of the art view of projects) based on relevant success criteria. Here the methodology of conformance (value protection) vs. performance (value creation) will also be included.

The Iron Triangle and its most common variations

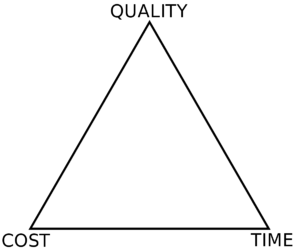

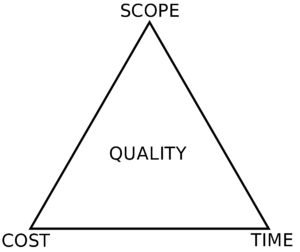

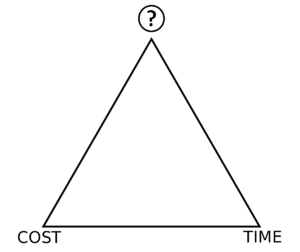

The Iron Triangle (also known as Project Management Triangle, Project Triangle, and Triple Constraint Triangle) is an essential tool that aims to present the concept of which project success should be understood. The Iron Triangle was proposed by Martin Barnes back in 1969 [1] [2] and has since then undertaken various different takes on changes, additions, and updates. Throughout time, the Iron Triangle has always been represented by the key project performance metrics that any project success is measured by, defined as constraints; namely Time and Cost [3] [1]. However, as extensively and thoroughly analysed by the rather up-to-date What is the Iron Triangle, and how has it changed? (2018) [3], it is presented that depending on the given project specifications and other varying debatable factors, either Quality, Scope, Performance, or Requirements are most often applied interchangeably as the triangle's third constraint. So, in other words, the Iron Triangle aims to represent the constraints of whether a project is delivered on time, within its budget, and to an agreed extension of quality, scope, performance, or requirement. Hereby, the main focus of the tool is defined to be Project Management, as some of the most cited project management standards have somewhat aligned views of project success in comparison to the core principals of the Iron Triangle. For example, the Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge [4] presents a comparative overview of the success definition in Project, Program, and Portfolio Management as seen in the table below.

| Projects | Programs | Portfolios | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Success is measured by product and project quality, timeliness, budget compliance, and degree of customer satisfaction. |

A program’s success is measured by the program’s ability to deliver its intended benefits to an organization, and by the program’s efficiency and effectiveness in delivering those benefits. |

Success is measured in terms of the aggregate investment performance and benefit realization of the portfolio. |

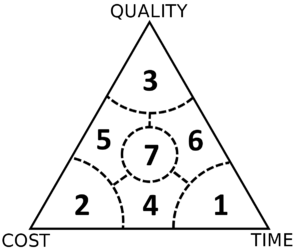

The Iron Triangle is most effective in displaying and communicating interdependencies between the above-presented success criteria. As seen in Figure 1 below, the classic depiction of the tool is a triangle with each constraint located at each corner of the triangle. The primary nature of the triangle’s constraint behaviour is formulated famously as “good, fast or cheap - pick two” [5], describing how the adjustment of focus in a specific constraint warrant compensating changes in one or both of the other constraints. With the Iron Triangle covering such core fundamentals of project management, it has been found that the neglection of its criteria can have devastating consequences on the success of a project in spite of efficient and effective management of other project metrics [4]. One of the newer and most popular depictions of the tool can be seen in Figure 2, where Quality is now defined as its own new dimension as the outcome of the Iron Triangle, while Scope has replaced its place as a constraint. The movement of accepting and replacing the Quality criteria truly took off with “Cost, time and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, it’s time to accept other success criteria” [6], where the method primarily was criticized for its heavy reliance of often unrealistic parameter estimation and un-flexible conditions of evaluating success by initial estimates. However, this is not the only documented limitation of the Iron Triangle which leads us to the next part of this article, the limitations of the Iron Triangle.

Limitations Caused by Simplicity and possible mitigations of these

Intro.

Error Type I

Error Type II

With such an old and fundamental tool as the Iron Triangle, it is of no surprise that research has pointed out some of the tool's most obvious limitations. Instead of saving the limitations of the Iron Triangle to the very end of this article, I'm instead going to address them here before the application process. The reason for this being, that this article thereby has the possibility of presenting not only the limitations but also well-known mitigations of these.

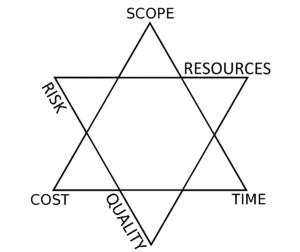

Research has increasingly started to suggest that although the Iron Triangle is important, it does not tell the whole story of project success. For example, Pinto and Pinto (1991) distinguished between short-term and long-term success criteria, categorizing the Iron Triangle as a short-term set of criteria, compared to criteria such as project benefits. Badewi (2016) argued that a strong focus on the Iron Triangle creates an overly output-focused mentality. Too much focus on the Iron Triangle can limit organisational effectiveness in realising benefits, and in the distribution between project managers and functional managers authority and responsibility (Maylor et al, 2006). In addition, Turner and Zolin (2012, p. 12) note that “…evaluations of project success by stakeholders are inherently subjective and cannot be summarized naively into the iron triangle without under or overestimating project success at critical points in the project life cycle.”

Especially

However, the reason for the Iron Triangle to be such a popular tool is its simplicity. This however, can be a double-edged sword as... So while these newer modifications of the premise of the Iron Triangle does make good attempts in solving one of the Iron Trinagle's main limitations, I think these also remove one of the tool's most appealing attributes; its simplicity. Therefore, when presenting the application process of the Iron Trinagle below, it is going to be with the focus on Pollack et al. conclusion of the essence of the Iron Trinagle being Time, Cost, and Quality.

Test [3]

Test [7]

Test. [4]

Test. [1]

Test. [6]

Test. [8]

Test. [9]

Test. [2]

Test. [5]

Test. [10]

Test. [4]

Application of the Iron Triangle

Constraint Management

Planning:

- what the constraints/ tolerances should be (if they have not been previously defined),

- who should be setting them (and when),

- how they are to be used by the project manager,

- how the sponsor/ stakeholders/ Project Board will be kept informed of the status of the constraints and project.

Controlling

- determining what is going on in the project (standard data collection/ monitoring processes),

- assessing how that compares against the constraints/ tolerances the sponsor/ stakeholders/ Project Board have agreed to with the project manager,

- whether any of the constraints/ tolerances been breeched – or threaten to be breached,

- proposing and recommending alternatives for addressing the breech.

Constraint Balancing

As discussed above, it should be clear that the project manager should clrealy define the key success criteria that works the best for them. In this application part, we are going to work with the classical Time, Cost, and Quality as [3] concluded that while the third criterion of Quality could be replaced by other depending on the definition of the project in question, that the Iron Triangle is defined by its classic triple constraint as it based on their analysis was found that these three concepts are highly interconnected, more so than any other combination of project management concepts. So, while still acknowledging that Time, Cost, and Quality is not defined as 'fit for all' projects, this application process making use of exactly these for the sake of generalzation and common ground.

One should not blindly assume that Quality is the most fitting constarint to their specific project. Take NASA for example; they...

Avoid Tunnel Vision

To not apply the Iron Triangle as its own stand alone tool. Must not neglect Business Case, Vision, Long-Term benefits, and priorities (what are the ACTUAL success criteria of this very project?)

Annotated bibliography

Key references:

A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide), 6th Edition (2017)

Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, 6th Edition (2017)

Bibliography

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wright, Andrew, and Therese Lawlor-Wright. “Project Success and Quality: Balancing the Iron Triangle.” Project Success and Quality: Balancing the Iron Triangle, Taylor and Francis, 2018, pp. 171–177. doi:10.4324/9781351213271.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Vahidi, Ramesh & Greenwood, David. (2009). TRIANGLES, TRADEOFFS AND SUCCESS: A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF SOME TRADITIONAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT PARADIGMS. 10.13140/2.1.2809.1520.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Pollack, J., Helm, J. and Adler, D. (2018), "What is the Iron Triangle, and how has it changed?", International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 527-547.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Project Management Institute, Inc. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition) - 2. Initiating Process Group. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). pp. XXX. Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt011DXQ4C/guide-project-management/initiating-process-group

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Van Wyngaard, C. & Pretorius, Jan-Harm & Pretorius, Leon. (2012). Theory of the triple constraint — A conceptual review. 1991-1997. pp. 1192-1195 10.1109/IEEM.2012.6838095.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roger Atkinson, Project management: cost, time and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, its time to accept other success criteria, International Journal of Project Management, Volume 17, Issue 6, 1999, Pages 337-342.

- ↑ AXELOS. Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2 2017 Edition, The Stationery Office Ltd, 2017. pp. XXX. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.findit.dtu.dk/lib/DTUDK/detail.action?docID=4863041.

- ↑ Gabriella Cserháti, Lajos Szabó, The relationship between success criteria and success factors in organisational event projects, International Journal of Project Management, Volume 32, Issue 4, 2014, Pages 613-624. ISSN 0263-7863.

- ↑ Test. Pinto, J., Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2010, pp. 35-40.

- ↑ T. S. Mokoena, J. H. C. Pretorius and C. J. Van Wyngaard, "Triple constraint considerations in the management of construction projects," 2013 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Bangkok, Thailand, 2013, pp. 813-817, doi: 10.1109/IEEM.2013.6962524.