Earned Value Management (EVM)

Abstract

When managing projects, it is of greatest interest to make sure that the project delivers what has been agreed upon. To make sure that expectations are fulfilled performance measurements can be used. Performance measurements allow the project manager and other stakeholders to closely monitor the project and decide more easily when it is necessary to take actions, if the project is running out of line. Projects that are not monitored properly run the risk of being late, overrunning the budget and ending up being out of scope, which can often lead to unsatisfied stakeholders. [1] Earned value management is a method used in project management to evaluate the performance of a project at any point to monitor whether or not the project is proceeding according to plan. This is done by comparing the actual outcome to the expected outcome of the three constraints: cost, time, and scope.[2][3] The result of the performance measurement is a value which indicates how much the current state of the project varies from the expected progress with cost, time, and scope taken into account. This value can later be used to forecast when the project will be finished and at what cost, if it proceeds at the current pace. [4]

This article aims to explain the purpose and concepts of earned value management, which prerequisites that need to be fulfilled, and how it can be applied in order to improve the outcome of projects. Further, a short case is presented to provide a better understanding of how the concept is used in practice. Finally, the article highlights the benefits and limitations of the concept.

Contents |

What is Earned value management?

Earned value management (EVM) is a method used throughout the entire project life cycle to measure the performance of projects, programs, and portfolios. The use of EVM dates back to the 1960s when the United States Department of Defense implemented a similar system to measure project performance in order to control cost and schedule. It was first implemented as many projects had become more expensive and had been delivered later than anticipated. [5][6] EVM mainly consists of the three elements that often play a big role in project management; budget of cost, project schedule as well as scope of work. The main idea of EVM is to integrate these elements to develop a baseline which can be used and compared to the actual outcome of the project at a certain point. It is thereby important that these elements are established with care when the project is planned. The difference between the traditional cost management and EVM is the additional component earned value, which is used to measure the actual accomplishment based on the budgeted cost, what the actual cost is and how this relates to the schedule. An example of what the additional component measures could be "after spending 50 percent of the budget, is 50 percent complete?"[7] EVM allows project managers to integrate these already organized components to forecast the end date and final cost of the project, which then can be used to visualize the project status. Visualization is often a powerful tool, as it can be used to make sure that all stakeholders in a project have the same picture. Visualization also makes it easier to identify issues which allows the stakeholders, such as the project manager, to make efficient decisions based on objective data. [1][8][5] Due to the characteristics of EVM it is highly connected to various key areas within projects such as cost management, schedule management, scope management, risk management and integration management.[1] EVM can be seen as a critical method when it comes to project planning, execution and control as these areas are often related to measuring, analyzing and forecasting. [2]

Application

This section begins with a brief description of terminology that is crucial to EVM. Further, it explains how EVM is applied to a project from a theoretical standpoint starting with setting up the baseline and deciding which measurement values to use to measure earned value. This is followed by an overview of how the analysis is conducted and how to use these values to forecast the expected cost of the project if it continues at the current pace. The section is finished off with a practical application of EVM on a fictional case.

Terminology

There are three main components when working with earned value management, planned value (PV), earned value (EV) and actual cost (AC). PV is the cost budget for the work that needs to be done related to a certain point in time. The planned value often relates to the cost for a certain activity hence the term budget at completion (BAC) is also commonly used, referring to the total budget for the project. EV is the component that is unique to EVM and can be seen as a measurement component which describes how effectively the money has been spent on the project. EV is simply calculated by multiplying the budget with the percentage of work done. The amount of work done completed can be calculated in various ways depending on the characteristics of the activity, this will be covered in the coming sections. The final component, AC, measures how much money that was needed to accomplish what has been done so far in the project. To compare these different values it is important that all the variables use the same unit. It is common that either work hours or currency is the unit of choice. When conducting forecasts using EVM common terminology is estimate at completion (EAC) and estimate to completion (ETC). EAC is the estimated cost that the project will have upon completion while ETC is the remaining amount of money that needs to be spent in order to complete the project.[9][7]

Step 1: Deciding the baselines

In order to successfully apply EVM there are a few important steps to go through. One of the most crucial steps is to define the different baselines of the project. The baselines that need to be decided are the scope baseline, schedule baseline and budget baseline. These baselines are used to generate what is known as the performance measurement baseline. The performance measurement baseline reflects the expected outcomes of the budget, schedule and scope, known as PV when the model is applied to the project. As the performance baseline will reflect what the project is expected to deliver at different times, it is important that the underlying baselines are determined correctly. It is also important that the performance measurement baseline is determined with consideration to the fact that changes may occur to budget, scope or schedule during the project.[2][7]

To accomplish this it is important that the scope of work is converted into a more distinct component already in the planning phase of the project. This can be done systematically by using the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). A well defined WBS can thereby be seen as a core component in EVM as the different baselines are developed from the WBS. The lowest level of the WBS, also known as the work package, usually consists of a small number of measurable activities such as a product, service or action that needs to be delivered.[5][2] In addition to the WBS the WBS dictionary is also developed. This is a document that explains each activity in the WBS in more detail. At this step the scope of work, WBS and WBS dictionary can be approved and form what is known as the scope baseline for the project.[1] Further, the schedule of the project can be decided with the scope baseline and resource breakdown structure as a base. When the project schedule is approved, the schedule baseline for the project is set. When applying EVM the schedule baseline will work as a base to compare the actual outcome of the project from a time perspective. [2] The final baseline that needs to be set is the budget baseline. In order to set this baseline the budget itself first has to be decided and approved, which is done by assigning costs to each element in the WBS. However, the budget also needs to include a lot of other elements such as the management reserve - a pot of money reserved for unknown management control purposes. The contingency reserve is - a pot of money reserved to manage risk. When deciding on the budget baseline it is important to keep in mind that the project may change along the way as well as to make sure that all costs are included.[2][5]

Step 2: Measuring earned value

It is important to decide which method that should be used to measure the EV of the project. As different work packages have unique characteristics, there are three different classes of work that are used depending on the character of the work package. These three work classes are discrete effort, apportioned effort, and level of effort.

ALT 1

Discrete effort

Work packages are identified to belong to the discrete effort work class if it is an activity that is a tangible product or service that can be measured. An example of an activity that belongs to this work class could be to put the tires on a car. If this is expected to take four hours, then we can assume that after one hour 25% of the tires are mounted.[2] However, measuring the work done using this method is only one way that discrete effort can be measured. Discrete effort can also be measured by for example using fixed formula, weighted milestone or, as the example suggests, physical measurement.[2][9]

- Fixed formula is a method where a certain percentage of earned value is gained when the activity is started and the rest is assigned when it is finished. This is suitable for work packages that can be finished quickly.

- Weighted milestones are suitable for work packages that take a long time to finish. Several milestones are set up for the work package, each adding a certain amount of earned value when reached.

Apportioned effort

If the work does not deliver a specific output but is a support activity for the discrete effort activities, such as quality checks or inspection, the work can be considered to be apportioned effort. The apportioned effort is directly connected to the discrete activity, therefore appointed effort activities are often set to be equal to the value of the discrete activity itself.[9]

Level of effort

The final work class that activities can be assigned to is level of effort. An activity is considered to be a level of effort activity if it does not directly produce a product or service that can be measured but is a necessary activity for the project. Example of a level of effort activities could be team lead, accounting, or customer relationship management. Earned value for level of effort activities are often very difficult to calculate, hence it is usually calculated as money spent on the activity divided by the total budget for that activity.[9] Too much time is often spent trying to find the perfect technique to measure the specific activity. It is important to remember that this measurement is an estimate. It is more important to focus on finding the optimal technique for larger value work packages, as these have a larger impact on the overall than the smaller work packages. [9]

ALT 2

- Discrete effort

- - Work packages are identified to belong to the discrete effort work class if it is an activity that is a tangible product or service that can be measured. An example of an activity that belongs to this work class could be to put the tires on a car. If this is expected to take four hours, then we can assume that after one hour 25% of the tires are mounted.[2] However, measuring the work done using this method is only one way that discrete effort can be measured. Discrete effort can also be measured by for example using fixed formula, weighted milestone or, as the example suggests, physical measurement.[2][9]

- Fixed formula is a method where a certain percentage of earned value is gained when the activity is started and the rest is assigned when it is finished. This is suitable for work packages that can be finished quickly.

- Weighted milestones are suitable for work packages that take a long time to finish. Several milestones are set up for the work package, each adding a certain amount of earned value when reached.

- Apportioned effort

- - If the work does not deliver a specific output but is a support activity for the discrete effort activities, such as quality checks or inspection, the work can be considered to be apportioned effort. The apportioned effort is directly connected to the discrete activity, therefore appointed effort activities are often set to be equal to the value of the discrete activity itself.[9]

- Level of effort

- - The final work class that activities can be assigned to is level of effort. An activity is considered to be a level of effort activity if it does not directly produce a product or service that can be measured but is a necessary activity for the project. Example of a level of effort activities could be team lead, accounting, or customer relationship management. Earned value for level of effort activities are often very difficult to calculate, hence it is usually calculated as money spent on the activity divided by the total budget for that activity.[9] Too much time is often spent trying to find the perfect technique to measure the specific activity. It is important to remember that this measurement is an estimate. It is more important to focus on finding the optimal technique for larger value work packages, as these have a larger impact on the overall than the smaller work packages. [9]

Step 3: Analysis

When all the necessary measures are collected the next step is to analyse the results. The analysis can be done by calculating various variances as well as indices such as schedule variance(SV), cost variance(CV), schedule performance index(SPI) and cost performance index(CPI). The SV can describe whether the project is on time or not by subtracting PV from EV (EV-PV). A positive number here indicates that the project is ahead of the schedule as a greater EV than what was expected has been reached. The CV can be used to evaluate how efficient the money is spent and is calculated by subtracting AC from EV (EV-AC). A negative value here indicates that the project has spent more money than expected to reach a certain EV level, meaning the project is overrunning the budget. This is usually more critical than overrunning the schedule, as it is more difficult to recover from.[7][9] CPI and SPI are indices that indicate how well every dollar was spent. CPI is calculated by dividing EV with AC (EV/AC) where a value above one is preferred, as this shows that more EV was gained from each dollar spent than what was anticipated the project runs ahead of plan. Just like CPI, SPI measures how much was expected to be completed at the current time by dividing the EV with PV (EV/PV). A value greater than one indicates that more work has been accomplished than what was planned at the current time, meaning the project is running ahead.[7] It is important that these measurements are individual for each project and therefore the performance between different projects cannot be compared to each other by for example looking at the index values. However, when monitoring a certain project these values can be very useful as trigger levels can be set to make sure that actions are taken whenever a certain measure is crossing a certain value.[7]

Step 4: Forecasting

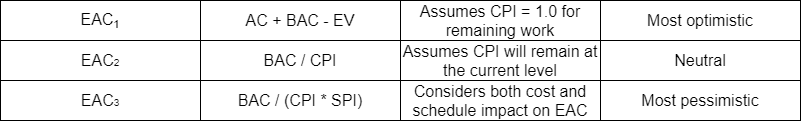

Once the analytic measures are calculated the future progression of the project can be forecasted, calculating the final outcome of the project if it continues at the current pace with regards to cost and time. By using CPI and SPI it is possible to forecast the expected additional cost needed to complete the project known as estimate to completion (ETC), as well as the estimate at completion (EAC). EAC can be compared to the total budget at completion, BAC, to assess the current risk of the project.[7][9] There are different ways to calculate the EAC which will give different results. Some of the methods gives a more pessimistic view on late projects while other calculating methods provide a more optimistic view. While it may be possible to forecast using only one EAC value, calculating a range by using two values may be favourable as both the optimistic and pessimistic values can be displayed. The three most common formulas used for EAC are presented in Figure 1.[9] The ETC can be calculated by subtracting AC from EAC, resulting in a value that shows how much money that is expected to be spent in order to complete the project.[7]

A practical example on how to apply EVM

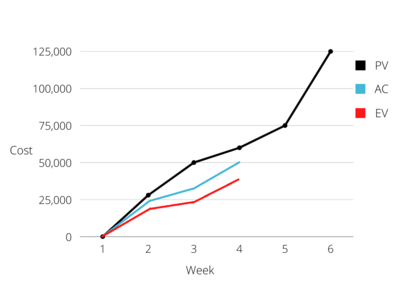

Imagine the following situation. A construction project has just begun and the foundation for a particular building needs to be constructed. The foundation is planned to cost $60000 and be finished in week 4, while the total budget for the project is set at $125000. When week 4 comes around, it turns out that only $50000 has been spent of the $60000 budgeted. By using a measurement method that was decided before the project began, the project manager notices that 60% of the work has been completed. As it turns out, the PV is $60000 while the AC is $50000, however; the EV is only 0.60*60000 = $36000. This means that while $50000 has been spent, the EV achieved at this point is only $36000. A graphical example of this can be seen in Figure 2.

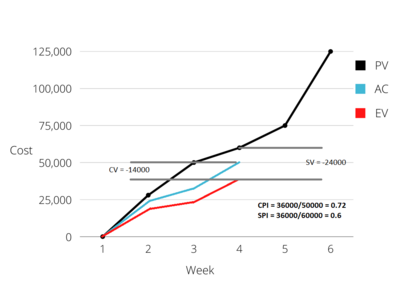

By applying the analysis measures CV, SV, CPI and SPI it can be noticed that the CV is $-14000 while the SV is $-24000. Turns out that the project is behind both with regard to time and cost. This can also be seen by looking at the index values where the CPI is 0.72 and the SPI is 0.6.[9] A graphical illustration can be seen in Figure 3. The project manager makes the other stakeholders aware of the situation, and the investors ask for a forecast of the final cost if the project proceeds in the same manner. The project manager decides that EAC1 is a good way to calculate the EAC in this case, see figure 1. Using EAC1 this results in a final cost for the project of $139000, $14000 above budget. In order to not overrun the budget actions must be taken by the managers in charge.

Benefits and limitations

With the use of EVM projects can be tracked by the use of objective measurements and the progress can be communicataged to to the stakeholders. EVM can also provide early warnings when the project is overrunning either cost or schedule, increasing the ability for managers to take proactive actions.[7] However successfull application of EVM requires a lot of requisites that need to be fulfilled in order to be able to apply it to the project at all, meaning a lot of resources are necessary to make it work. EVM therefore often requires a significant investment to be made, making it more suitable for larger projects. However, lighter, alternative versions such as EVM lite can be applied to smaller projects.[10][6] In addition, EVM does not take the quality of the work that has been done into account. While the work may be done, it may not actually have earned the value if it is not done properly.

Nevertheless, EVM has proven to be beneficial for use in a large variety of different projects in various industries such as construction[11], software development[12] and energy[13]. With continuous developments and improvements to make the method more viable by for example using it to measure performance of sustainability goals in projects[14], as well as combining it with agile[15], it is very likely that EVM will remain a very useful method.

Annotated bibliography

Project Management Institute (2012) Practice standards for earned value management. 2nd ed. Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute.[2]

The Practice standards for earned value management is the official standard for earned value management. It provides a detailed framework over what earned value management is and which role it plays when it is applied in project, program, and portfolio management. The goal of the standard is to encourage the use of earned value management to improve the project performance. The standard comprises a lot of information and describes earned value management in a broad context highly connected to other areas in project, program, and portfolio management.

Earned Value Management (EVM) Implementation Handbook. (2013). In NASA Center for AeroSpace Information (CASI). Reports. NASA/Langley Research Center.[16]

The implementation handbook was developed to be applied by the personnel at National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The handbook presents a framework of how earned value management should be applied in their projects and programs. As NASA is a large corporation, this handbook provides a detailed example of what a large corporation using EVM finds important. The handbook looks further into areas considered in this article, such as requirements, baselines, and implementation. But also puts further attention into areas that have not been highlighted, such as the area of roles and responsibilities.

Joseph A Lukas (2008) ‘Earned Value Analysis - Why it Doesn’t Work’, in AACE International transactions. 2008 Morgantown: American Association of Cost Engineers. p. EV11–.[9]

Joseph A Lukas is a former consultant who used to help companies figure out corrective actions to get their earned value analysis back on track. The article explains what earned value analysis is and how it is applied and corrective actions that should be taken. Further, the article discusses the top 10 pitfalls organizations usually face when applying earned value analysis. Finally, the author discusses what causes these pitfalls which generally comes down to the preparation of the project.

Kwon, O.-C. et al. (2008) “Application of earned value in the Korean construction industry — A case study” Journal of Asian architecture and building engineering, 7(1), pp. 69–76.[11]

Hanna, R. A. (2009) “Earned Value Management Software Projects” in 2009 Third IEEE International Conference on Space Mission Challenges for Information Technology. IEEE.[12]

Urgilés, P., Claver, J. and Sebastián, M. A. (2019) “Analysis of the Earned Value Management and Earned Schedule techniques in complex hydroelectric power production projects: Cost and time forecast” Complexity, 2019, pp. 1–11.[13]

PROBABLY DELETE THIS The three articles above presents the use of earned value management in three different industries and highlights the complications and the complexity that arises in the different industry. In Korea for example the government has put a legislation in place that forces construction projects worth more than $50 million to apply earned value management after the benefits that has been seen by using it. This article provides a case study of how that works out on a particular project. The second article looks into how EVM can be used in software projects, an area that has proved to be particulary difficult. The article mainly discusses the challenges which often comes down to uncertainty and how software projects successfully can apply EVM by reducing uncertainty. The third article analyzes how effective EVM is when it comes to managing very complex and cost intensive hydroelectric power production projects.

Koke, B. and Moehler, R. C. (2019) “Earned Green Value management for project management: A systematic review” Journal of cleaner production, 230, pp. 180–197.[14]

As sustainability is becoming more and more important in our daily life as well as in project this article aims to investigate whether EVM can be adapted to not only measure scope, time, and cost but be adapted to also measure the performance of sustainability goals in projects. The authors develop a framework known as Earned Green Value Management which is developed to bridge the gap between sustainable project management and traditional project management.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Project Management Institute (2017) A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide). 6th ed. Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Project Management Institute (2012) Practice standards for earned value management. 2nd ed. Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Sparrow, H. (2002). Integrating scheduling and earned value management (EVM) metrics. Paper presented at Project Management Institute Annual Seminars & Symposium, San Antonio, TX. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Levine, H. A. (2005) Project portfolio management: A practical guide to selecting projects, managing portfolios, and maximizing benefits. London, England: Jossey-Bass.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Stephen P Warhoe (2004) The Basics of Earned Value Management. AACE International transactions. CS71–.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Vanhoucke, M. (2009) Measuring time: Improving project performance using earned value management. 2010th ed. New York, NY: Springer.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Chen, M. T. (2008) ‘The ABCs of earned value application’, in AACE International Transactions. 2008 Morgantown: American Association of Cost Engineers. p. EV31.

- ↑ Anbari, F. T. (2011). Advances in earned schedule and earned value management. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2011—North America, Dallas, TX. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 Joseph A Lukas (2008) ‘Earned Value Analysis - Why it Doesn’t Work’, in AACE International transactions. 2008 Morgantown: American Association of Cost Engineers. p. EV11–.

- ↑ Forman, J. B. & Somerville, D. (2009). EVM "lite"—a deliverables-based approach. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2009—North America, Orlando, FL. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kwon, O.-C. et al. (2008) “Application of earned value in the Korean construction industry — A case study” Journal of Asian architecture and building engineering, 7(1), pp. 69–76.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hanna, R. A. (2009) “Earned Value Management Software Projects,” in 2009 Third IEEE International Conference on Space Mission Challenges for Information Technology. IEEE.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Urgilés, P., Claver, J. and Sebastián, M. A. (2019) “Analysis of the Earned Value Management and Earned Schedule techniques in complex hydroelectric power production projects: Cost and time forecast” Complexity, 2019, pp. 1–11.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Koke, B. and Moehler, R. C. (2019) “Earned Green Value management for project management: A systematic review” Journal of cleaner production, 230, pp. 180–197.

- ↑ Sulaiman, T., Barton, B. and Blackburn, T. (2006) “AgileEVM - earned value management in scrum projects” in AGILE 2006 (AGILE’06). IEEE.

- ↑ Earned Value Management (EVM) Implementation Handbook. (2013). In NASA Center for AeroSpace Information (CASI). Reports. NASA/Langley Research Center.