Data-Driven Decision-Making under Uncertainty

Developed by Anton Reiling

There are several approaches to reach decisions under uncertainty under the assumption of reliable, fixed data. The degree of complexity and scope among the approaches differs considerably, which is why they should be selected according to the use case.

Starting with the simple approaches the Minimax and Maximax criterion consider the worst or best possible outcome of decision alternatives. The Hurwicz Criterion offers a mix between these two approaches depending on the predefined Optimism Parameter. The Minimax Regret Criterion considers the opportunity costs caused by choosing an alternative to reach a decision and the Laplace Criterion compares the expected values of the alternatives. However, due to simplifications and assumptions these methods are limited to rather simple problems with low complexity. This is because they lack the possiblity to assess risk, qualitative inputs and heterogenous probabilities for different outcomes.

For more complex problems, approaches like the Monte Carlo Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis can be used, while also requiring more effort to be conducted. There is also the concept of Robust Decision Making, which combines different tools to help to make better and more profound decisions.

All these approaches can be used within Project, Program and Portfolio Management, for example to compare two offers for Outsourcing Contracts within Project Management, which is illustrated later in this article. Depending on the decision-making approach different results will be yielded, which clarifies their respective focus and susceptibility to outliers.

Contents |

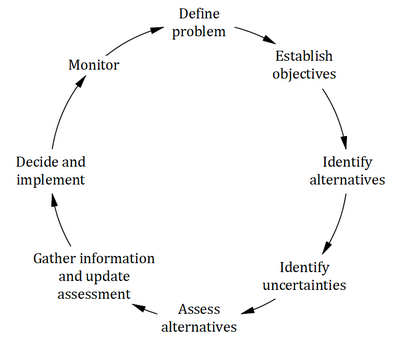

The Decision-Making Process

In order to reach a sensible decision for a specific problem, certain steps have to be followed:

- Step 1: Define the problem: Specify the problem framework with the respective requirements regarding costs, time horizon, etc.

- Step 2: Establish the objectives: Describe the objectives for the given problem to create a foundation to compare later alternatives on depending on their degree of fulfillment and performance.

- Step 3: Identify alternatives: Work out possible alternatives that can satisfy the objectives and narrow them down to a shortlist that can be examined under reasonable effort later.

- Step 4: Identify uncertainties: Elaborate possible scenarios that can inlfuence the utility or cost of alternatives and connect them to the alternatives with their respective values.

- Step 5: Assess alternatives: Conduct research or apply decision-making tools to find out, which alternative satisfies the given objectives best.

- Step 6: Gather information and update the assessment: Gather data to verify if the preferred alternative from step 5 is really the best alternative of all the available ones. In case crucial data was overlooked, repeat step 5.

- Step 7: Decide and implement: Make a final decision regarding which alternative to choose and assign tasks and responsibilities to it

- Step 8: Monitor: Continously track the progress of the implementation to be able to plan adjustments if necessary

Within the scope of this article, steps 5, 6 and 7 will be examined in further detail.[1] (Good Decision-Making: The Key to Project Success, p.14-16)

Fundamental assumptions

Differences between Decision-Making under Uncertainty and Risk

While decison-making under risk implies a certain probability for each possible outcome, decision-making under uncertainty assumes that these probabilites are unknown and thus each scenario is considered equally important. This subsequently leads to a higher inaccuracy of uncertainty problems compared to risk problems. An example for that would be a problem with 3 possible outcomes: Best case, most probable case and worst case. While for decision-making under risk the both extreme scenarios would be considered with a presumable low probability and thus weight, for decision-making under uncertainty all of the outcomes would be regarded in the same way, which means that in this case outliers have a considerably higher impact to the decision.

[2] (p. 607)

Decision-Making Approaches

Minimax Criterion

The Minimax or Maximin approach shows a pessimistic conception: Thus, only the worst possible outcome of each alternatives is taken into accout and compared with the others. This means that all of the outcomes for the remaining scenarios remain unconsidered.

[3](ref: Development of fuzzy multi-criteria approach, p. 507)

Maximax Criterion

The Maximax or Minimin Criterion works opposite to the Minimax approach: Here, the best possible outcome is considered, which means that all other outcomes are ignored.

[3](ref: Development of fuzzy multi-criteria approach, p. 507)

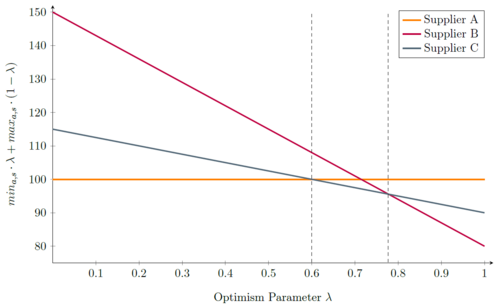

Hurwicz Criterion

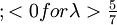

The Hurwicz Approach acts as a combination of the Minimax and the Maximax Criterion. Depending on the Optimism Parameter ![\lambda \in [0;1]](/images/math/1/a/5/1a5a7711ae11da16d07f2a95797cf7b6.png) this approach can represent a rather optimistic or pessimistic attitude towards the outcomes of the examined alternatives. As extremes,

this approach can represent a rather optimistic or pessimistic attitude towards the outcomes of the examined alternatives. As extremes,  would correspond to the Maximax Criterion and

would correspond to the Maximax Criterion and  to the Minimax Criterion.

to the Minimax Criterion.

[3](ref: Development of fuzzy multi-criteria approach, p. 507)

Minimax Regret Criterion

The Minimax Regret Criterion tries to minimize the opportunity costs by choosing one alternative.

[3](ref: Development of fuzzy multi-criteria approach, p. 507)

Laplace Criterion

The Equal Likelihood Criterion or Laplace Criterion compares the expected value of each alternative with each other. Thereby, every outcome is considered which means that outliers that would act as extreme values for the Minimax or Maximax Criterion will have a considerably lower importance with the Laplace Criterion.

[3](ref: Development of fuzzy multi-criteria approach, p. 507)

Comparison of the approaches

[2] (p. 607-608)

Application to Outsourcing Contracts within Project Management

These approaches can also be applied to Project, Program and Portfolio Management. However, since they assume that the given data is certain per scenario and can be expressed as a number, the range of sensible application descreases. One example for utilizing these approaches are simple decisions regarding choosing suppliers for Outsourcing.

Let's take the following example to see how the different methods influence the decision which supplier to select: For a software project, parts of the front-end development are outsourced to a third-party supplier, which needs to be chosen according to their costs. Since mostly supplier and customer agree on a quotation with a cost estimate  , the resulting costs

, the resulting costs  can be higher or lower than the estimate, depending on incidents during the projects like delays, reworking or other unplanned costs. Of course, some additional costs are already included in the cost estimate to grant the supplier a buffer. This example will consider the following 5 scenarios:

can be higher or lower than the estimate, depending on incidents during the projects like delays, reworking or other unplanned costs. Of course, some additional costs are already included in the cost estimate to grant the supplier a buffer. This example will consider the following 5 scenarios:

- Scenario 1: Best scenario: None of the predicted costs actually occured:

- Scenario 2: The actual costs are lower than the estimated costs, but not as low as

:

:

- Scenario 3: The actual costs match the estimated costs:

- Scenario 4: The actual costs are higher than the estimated costs, but not as high as

:

:

- Scenario 5: Worst scenario: On top of the predicted costs a high number of unexpected costs occurs which increases the overall costs drastically:

The following two suppliers can be chosen: Supplier A guarantees a fixed price of 100 monetary units, no matter which scenario will ocur (i.e. how many unexpected costs will occur). Supplier B however, proposes and estimated price of 100 monetary units. The actual price can vary depending on the scenario, which the following table illustrates:

| Suppliers | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier A | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Supplier B | 80 | 95 | 100 | 105 | 150 |

Applying the described approaches to this problem yields the following results:

- Minimax Criterion:

→ Supplier A

→ Supplier A

- Maximax Criterion:

→ Supplier B

→ Supplier B

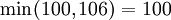

- Hurwicz Criterion:

![[\min(a=2,s) * \lambda + \max(a=2,s) * (1-\lambda)] - [\min(a=1,s) * \lambda + \max(a=1,s) * (1-\lambda)] > 0 for \lambda < \tfrac{5}{7}](/images/math/2/5/8/258ef7438c7256016a87b95ece1b364e.png) (→ Supplier A)

(→ Supplier A)  (→ Supplier B)

(→ Supplier B)

- Minimax Regret:

→ Supplier A

→ Supplier A

- Laplace Criterion:

→ Supplier A

→ Supplier A

It can be seen that due to the assymetric distribution towards higher average costs for Supplier B the Minimax Regret and the Laplace Criterion suggest to choose Supplier A. For the same reason the Hurwicz Criterion suggests to choose Supplier A for a higher Range in  than to choose Supplier B. Since we have costs independent from the scenario for Supplier A it stands to reason that the Minimax Criterion suggests Supplier A and the Maximax Criterion Supplier B.

than to choose Supplier B. Since we have costs independent from the scenario for Supplier A it stands to reason that the Minimax Criterion suggests Supplier A and the Maximax Criterion Supplier B.

It can be critisized that only the costs were considered in this example and not features like reliability or service quality. Also, all the outcomes were assumed to have an equal probablity of happening which is also rather unrealistic. Especially considering scenario 5 equally probable put a high weight on the 150 monetary units of Supplier B for this scenario. However, for minor supplier selection decisions these approaches provide results with low effort.

Limitations

.

Annotated bibliography

.

References

- ↑ Shaltry, P. E. (2009). Book Review: The Project Manager’s Guide to Making Successful Decisions. Project Management Journal, 40(4), 107–107.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kerzner, H. R. (2017). Project management: A systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling (12th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Chung ES, Kim Y. Development of fuzzy multi-criteria approach to prioritize locations of treated wastewater use considering climate change scenarios. J Environ Manage. 2014 Dec 15;146:505-516. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.08.013. Epub 2014 Sep 11. PMID: 25218330.