Effort-Reward-Imbalance

Contents |

Abstract

In 1986, Johannes Siegrist, a medical sociologist and university professor, designed the Effort-Reward-Imbalance Model to predict and explain the effects of high effort with low return on the health of the heart (Van Vegchel et al., 2005). This model has been further developed over the years and is used today to understand the effects of work on the health of the employee, in order to ideally prevent diseases. The model is designed to assess negative effects and stressful experiences at work and predict probabilities of illness. This imbalance can lead to a range of health problems such as stress, burnout, and depression (Siegrist, 1996). Three primary hypotheses can be derived from the ERI model. First, the external ERI hypothesis, which states that high effort combined with low reward increases the risk of poor health. Second, the internal overload hypothesis can be derived from the model. The core message of this hypothesis is that a high, critical level of overcommitment also increases the risk of deteriorating health. These two hypotheses are ideally rounded out with the interaction hypothesis, which suggests that it is primarily the combination of too much effort combined with low reward and the assumption of too much obligation in the form of overcommitment that leads to an even higher risk of stress reactions (Peter et al., 2002).

This article reviews the structure and idea of the model, the hypotheses, the methodology, the impact on health, and possible limitations and management implications.

Structure and idea of the model

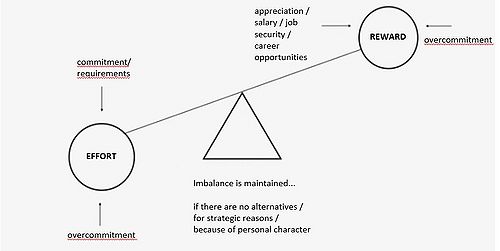

The goal of the model is to combine sociological information describing the work environment or setting, psychological information describing relevant person characteristics, and biological information describing immediate or long-term health outcomes. The model addresses the challenge of answering the question of what critical components of work life influence human health (Siegrist, 1996). It is composed of three components, "effort," "reward," and "overcommitment," although "Overcommitment" was first added to the model in 1999 (see figure 1).

The effort is described in the model as the employee's obligation to the employer (Van Vegchel et al., 2005). The concept of high effort can be divided into high extrinsic effort and high intrinsic effort. Extrinsic effort is the caused stress from outside, for example, in the form of work pressure or the general demands of the job. The high intrinsic effort defines above all the need for control, or the own motivation in a demanding work situation. Reward is described in the Effort-Reward-Imbalance model as professional reward in the form of money, appreciation and state control. In the model, the concept of state control, i.e., control over one's own occupational own professional status, is highly relevant. This includes the availability of advancement opportunities and job security. The combination of these two conditions of low reward coupled with high effort can have negative effects on various areas of job satisfaction, but especially on health.

Hypotheses

Three primary hypotheses can be derived from the ERI model. First, the external ERI hypothesis, which states that high effort combined with low reward increases the risk of poor health. Second, the internal overload hypothesis can be derived from the model. The core message of this hypothesis is that a high, critical level of overcommitment also increases the risk of a deteriorating health state. These two hypotheses are ideally rounded out with the interaction hypothesis, which suggests that it is primarily the combination of too much effort combined with low reward and the assumption of too much obligation in the form of overcommitment that leads to an even higher risk of stress reactions (Peter et al., 2002).

Methodology used in project management

Since 1996, the Effort-Reward-Imbalance-Questionnaire has typically been used to determine the imbalance between effort and reward. In practice, this questionnaire is also used in the context of general management activities and project management tasks to determine the stress level of team members in a project (Van Vegchel, 2005). The questionnaire designed by Siegrist measures extrinsic effort, reward, and overcommitment, the three components of the ERI model. Extrinsic effort is measured using a scale consisting of six items related to the demanding aspects of the work environment (Stanhope, 2017). For example, project members are asked if the worker is under constant time pressure due to a heavy workload. If the participant answers in the affirmative, the participant is then asked to rate the severity of this situation on a Likert scale. By asking questions of this type, it is possible for the project manager to better manage the workload of his or her employees (Hanson et al., 2000). Other items measuring extrinsic effort include physical workload, potential interruptions, level of responsibility, number of overtime hours, and increasing demand. The Reward Scale consists of 12 items that include two subscales, appreciation and status Control.

The esteem scale contains five items, for example, the subjectively perceived respect that employees receive from their colleagues and managers. Status control is measured with six items, including the item of opportunity for promotion (Hanson et al., 2000). The operationalization of overcommitment has changed repeatedly over the years. The most modern versions of the questionnaire contain 5 items designed to measure the employee's ability to switch off from work after a day's work. The ability to switch off from work was declared to be the most important item (Niedhammer et al., 2000). Another item measures the participant's irritability.

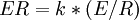

For each item, a minimum score of 1 and a maximum score of 4 must be achieved. To identify Effort-Reward Imbalance, the ratio is calculated as follows: with

with  for Effort,

for Effort,  for Reward, and

for Reward, and  as a corrective variable with

as a corrective variable with  . An imbalance exists if

. An imbalance exists if  is not equal to 1. When the value of

is not equal to 1. When the value of  is less than -1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of reward and when

is less than -1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of reward and when  is greater than 1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of effort (Stanhope, 2017).

As a project manager, its common to use these results to rethink one's behavior toward team members in a project in terms of whether to increase reward or decrease effort.

is greater than 1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of effort (Stanhope, 2017).

As a project manager, its common to use these results to rethink one's behavior toward team members in a project in terms of whether to increase reward or decrease effort.

Impact on health

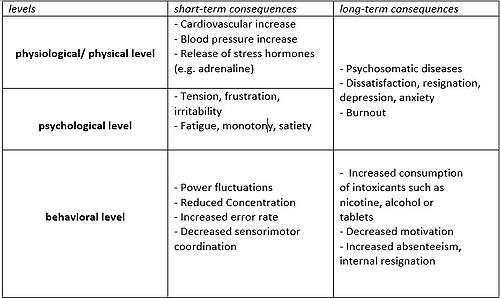

Health effects can be divided into physiological, mental, physical, and behavioral. A meta-analysis by Faragher et al. from 2005 provides a systematic review from 485 studies with a total size of 267,995 study participants on job satisfaction and consequences on health. The calculation yields a combined overall correlation of job satisfaction and health of r=0.370. Accordingly, a valid positive correlation exists (Faragher et al., 2005). The model describes that health consequences can arise from persistent stress reactions. Factors that have a high probability of triggering a stress response are called stressors and play an important role in the relationship of the ERI model and the health of the worker (Greif, 1991). The consequences of stress reactions and stress differ on the temporal and content levels. On the one hand, short-term consequences exist, such as fatigue, monotony, or satiety, however, on the other hand, there are numerous possible medium- to long-term consequences, such as depression. On the content level, the consequences of stress on health differ between the physiological, psychological, physical and behavioral levels (see figure 2, Kauffeld et al., 2019).

Psychological/psychosomatic health effects

An imbalance of effort and reward can have negative influences on the psychological well-being of the individual. An example of this is a study in the Japanese nursing system from 2017, in which 17.9% of the 173 study participants stated that they suffered from high psychological stress. The Effort-Reward-Imbalance-Questionnaire was used as the survey baseline in the study (Honda et al., 2017). Two of the most common psychological stress disorders are burnout and depression. These psychological and psychosomatic health consequences are also relevant for project managers, as a possible long absence of the affected employee should be prevented.

Depression

The number of people currently suffering from depression is high. The German Depression Aid Foundation has determined that 11.3% of women and 5.1% of men in Germany suffer from depression. In terms of their severity, depression is one of the most underestimated diseases (Stiftung Deutsche Depressionshilfe, 2016). 2015, more people died by suicide (10,080) caused by depression in Germany than by drugs (1,226), traffic accidents (3,578), and HIV (371) combined (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015). Depression is expressed in the form of impaired mood, as feelings of dejection, anxiety, loss of pleasure, emotional emptiness, lack of drive, loss of interest, and numerous physical complaints (Hautzinger, 2010). Faragher et al's meta-analysis of 485 studies and 267,995 study participants calculated the correlation of job satisfaction and depression. The correlation is positive and is r=0.366. Accordingly, there is a positive relationship between job satisfaction and depression. The meta-analysis makes it clear that employees who are subjectively lower in the hierarchy of the company are more likely to suffer. If the work does not provide adequate personal satisfaction, or even causes dissatisfaction, this can develop into persistent psychological stress over a longer period of time. The associated lower self-esteem increases the chance of suffering from mild depression or anxiety. If this condition remains unresolved over an extended period of time, it can lead to emotional exhaustion, which can result in an increase in depression. In studies prior to 1980, the averaged correlation of job satisfaction and depression was r=0.424. This was followed by a slight increase to r=0.446 by 1990, but since 1990 the value has dropped to r=0.316 (Faragher et al.,2003). Workers with increased overcommitment have a 1.92-5.92-fold chance of experiencing psychosomatic symptoms such as depression compared to workers with low levels of commitment. The data reported by Van Vegchel et al. reviewed mostly only examined the relationship between Effort- Reward imbalance and overall psychosomatic health. The most of these studies found a positive correlation between ERI and psychosomati outcomes. Workers who work in a high-effort-low-reward situation have an increased chance of 1.44-18.55% psychosomatic outcomes, such as depression (Van Vegchel et al.,2005). An analysis of existing studies conducted by Johannes Siegrist 2006 conducted an analysis of existing studies supports the results collected so far. The combination of high effort and low reward increases the probability of a depressive disorder by 50 to 150%. The results are more consistent for men. Siegrist also confirms Faragher et al.'s hypothesis that the effects are more pronounced in groups with low occupational status (Siegrist, 2006).

Projectmanagement implications

Companies and project managers should recognize the importance of balancing effort and reward and implement it in their work. The consequences are too serious to financial interests over the health of workers. This requires a reordering of priorities. Of course, profit maximization must continue to be an important goal of a healthy company, but this must not impact the health of the workforce. Companies and project managers should develop strategies to manage stress and improve the working atmosphere. Large companies should be able to provide additional psychological care, especially for employees with diagnosed psychological problems. Finally, it should be Finally, it should be mentioned that adjusting the selection process for employee recruitment can prevent an imbalance. The requirement that awaits the applicant upon acceptance should be clearly defined. There should be no deviation from these clearly defined mental and physical requirements unless necessary. Adjustment to the requirement should still be possible on the part of the employer and the project manager, but only with simultaneous adjustment of rewards to maintain the balance of effort and reward. Maintaining the balance is also of great interest to the companies, as this reduces unwanted submissions of notices of termination.

References

Hanson, E. K. S., Schaufeli, W., Vrijkotte, T., Plomp, N. H. & Godaert, G. L. R. (2000). The validity and reliability of the Dutch Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.142

Honda, A., Date, Y., Maeta, S. & Honda, S. (2017). IMPACT OF EFFORT-REWARD IMBALANCE ON PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS IN JAPANESE CARE STAFF. Innovation in Aging, 1(suppl_1), 1107. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.4055

Faragher, E. B. (2005). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta- analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2002.006734

Fink, G. (2016). Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior: Handbook of Stress Series, Volume 1 (Handbook in Stress) (1. Aufl.). Academic Press.

Greif, S., Bamberg, E. & Semmer, N. (1991). Psychischer Stress am Arbeitsplatz. Hogrefe

Niedhammer, I., Siegrist, J., Landre, M. F., Goldberg, M., & Leclerc, A. (2000). Etude des qualites psychometriques de la version francaise du modele du Desequilibre Efforts/ Recompenses (Psychometric properties of the French version of the Effort–reward Imbalance model). Revue d’epidemiol et de sante publique, 48(5), 419–437.

Kauffeld, S., Ochmann, A. & Hoppe, D. (2019). Arbeit und Gesundheit. Springer-Lehrbuch, 305–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56013-6_11

van Vegchel, N., de Jonge, J., Bosma, H. & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Reviewing the effort–reward imbalance model: drawing up the balance of 45 empirical studies. Social Science & Medicine, 60(5), 1117–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.043

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27

Peter, R. (2002). Psychosocial work environment and myocardial infarction: improving risk estimation by combining two complementary job stress models in the SHEEP Study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 56(4), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.56.4.294

Stanhope, J. (2017). Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 67(4), 314–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx023