Front-end Sustainability: Initiating the right sustainable projects

Developed by Kristine Fisker

Projects, programs and portfolios shape our society and world permanently, by shaping the impact of the products, buildings, infrastructure and systems designed within them. One of the most critical questions for project management going forward will be how to aid in tackling the large, complex, and interlinked sustainability challenges that need to be solved for societies worldwide to survive and prosper[1].

The 'Fuzzy' Front-End, when a project is conceptualized and defined, is the stage which is most critical in determining the impact of a project, yet the Front-End of Eco-Innovation has received little attention by the field of project management [2] [3]. This article will describe how project, program and portfolio managers can achieve effective sustainable impact and increase resilience and opportunity creation for their organizations by increasing sustainability focus in the fuzzy front end.

Contents |

Why sustainability in the front end?

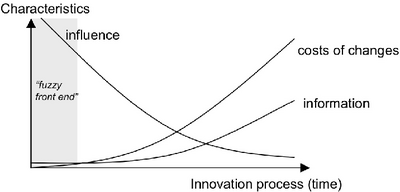

The 'Fuzzy' Front-End is the most uncertain, challenging part of projects, while at the same time being the part of the project that has the largest influence on final project impact (see Figure 1). "For companies to achieve true sustainability as opposed to a lower level of sustainability, considerations for sustainability have to be incorporated in early stages of the innovation process"[2].

"The ability to ‘eco-innovate’ may become increasingly important under growing global pressures (see e.g., Royal Society, 2012), and may become a new source of competitive advantage. Hence, mastering the FEEI would be a key to business success and longevity." ([2])

This article will be a high level overview of considerations and tools that project, program and portfolio managers can apply to transform front end processes for increased sustainability impact. As the link between the fuzzy front end and sustainability is an emerging field of study, this article can be read as a summary of current best practices within fuzzy front end- and sustainability management. The literature findings are structured in a sense-making framework inspired by advice in the article 'The fuzzy front-end of sustainability' by Chris Sherwin [3].

SDGs "By developing and delivering solutions for the achievement of the SDGs, companies will discover new growth opportunities and lower their risk profiles. Companies can use the SDGs as an overarching framework to shape, steer, communicate and report their strategies, goals and activities, allowing them to capitalize on a range of benefits."

"Global efforts by governments and others to deliver the SDGs will further strengthen financial value drivers of corporate sustainability, including: – The introduction of taxes, fines and other pricing mechanisms to make current externalities become internalized to the business."

Application

As described in the wiki-article Fuzzy Front End Management, the front-end process described the phases where project concepts are 1) searched for, and 2) a project concept is selected.

0. Allocate sustainability ressources to the fuzzy front-end

Because the fuzzy front-end is a highly insecure stage, there is an understandable tendency in organizations to go with a preconcieved idea of the technological solution to the problem, based on major assumptions, in order to make a manageable project definition [5] [6] [2]. As described by Olsson et al. "In too many projects, the initial idea remains largely unchallenged and turns out to become the selected project concept. The predominant tradition is to apply “downstream” analyses of the consequences of an already given alternative, rather than “upstream” assessment of alternative concepts as seen in relation to needs and priorities."[6]. Going with a preconcieved solution from the beginning can however be problematic, especially in a sustainability context [6], as the first assumed solution often is not ideal in terms of appropriateness or impact[7].

Picture this: a building department of a company basing all their sustainability projects on building new buildings with the highest sustainability certification, but never consider which buildings they could avoid building based on e.g. increased digitization of work and optimizing the utilization of current space. You can also picture a public procurement unit making calls for tenders calling for the most sustainable surgical scissor, rather than... A manager of a company having an idea for a sustainable product that there is no need for.

The very foundation of initiating the right sustainable projects is to recognize that the fuzzy front-end can in fact be managed with flexibility, without falling into the assumption trap of defining the solution too narrowly at the offset. Designers and design engineers are increasingly utilized for their competencies and methodologies in meaningfully managing the fuzz of the fuzzy front end. It is suggested that companies could prevent many down-stream sustainability issues from arising by reallocating just 10% of their sustainability budget towards front-end innovation, which could effectively 'design out' sustainability issues from the future portfolio[3][6].

1. Move from reactive to pro-active, value focused strategy

As sustainability is a new lense to view projects through, it requires rethinking... Move from reactive to pro-active.

"we concluded that there are three shifts that characterise the integration of sustainability and project management. Considering sustainability implies, firstly, a shift of scope in the management of projects: from managing time, budget and quality, to managing social, environmental, and economic impact. Secondly, it implies a shift of paradigm of project management: from an approach that can be characterised by predictability and controllability, to an approach that is characterised by flexibility, complexity and opportunity. And thirdly, considering sustainability implies a mind shift for the project manager: from delivering requested results, to taking responsibility for sustainable development in organisations and society."

Purpose driven.

2. Create conditions for explorative front-end innovation

Front-End 'Delivery' Unit The Front-End Innovation Unit

Hunter gathering

Future forecasting

Team makeup

3. Open up to external collaborative innovation

Management of meaningful sustainability projects, programs and portfolios can be especially complex, as the scope is beyond what a single organization, government or individual can solve alone.

"Individual organizations must be part of the solution, but they cannot be addressed within the organization alone or solved independently in other organizations." "The key to solving complex, systemic, long-term problems across sectors and levels is to address them together." [8]

LFA Logical Framework

Mission-Oriented Innovation and Open Innovation

OECD Mission Action Lab. Danish Design Center

Developing a Mission-driven Portfolio for Systemic Impact

The Mission Playbook by Danish Design Center. For ambitious, longterm impact across organisations. "mission managers who focus on achieving a long-term vision of change for a wide range of stakeholders instead of internal organizational development." [8]

Creating impact

(insert impact model)

"Creating impact means allowing room for the uncertainty that is an inevitable part of long-term missions. To create impact, we think less in single activities and more in portfolios. We must consider how to involve a wider field – for instance defined by a policy or market domain – to take part in achieving a concrete, measurable change. And most importantly, we must also set up mechanisms that facilitate a con- stant flow of learning from the activities we put in place, and have a manage- ment process in place that acts on these insights."

"Missions call for a structure that balances stability and agility – predictabil- ity and unpredictability. That means creating a governance structure for the mission work that leaves room for changing the project portfolio and the ac- tor landscape as the mission progresses. The foundation for making decisions like that is to build in loops of learning at the heart of the mission in order to constantly react and adapt to new learn- ings from both within and outside the mission ecosystem. This means, the task is not “just” to build the solution, but to create the sys- tem around the solution that makes its achievement possible. Value creation, then, becomes a task of working towards committing people to the mission in order to stimulate several smaller innovations that point in the same direc- tion rather than chasing the next big bang."

"This roadmap outlined not only project proposals, but “infrastructure” activities such as communication, new partnerships and investments in new tools and capabilities. Underpin- ning this we created a systematic learning mechanism - a process of on-go- ing portfolio assessment and adjustment. This mechanism turned out to be crucial in our management of the evolution of this mission."

[8].

Open Innovation: Going beyond the individual organization

Limitations

"The tools required for this can perhaps be mastered more easily in big, resourceful companies, but larger companies may have difficulties in allowing the eco-innovation process to be open, informal and creative, aspects which contributed positively to the success of novel eco- innovations." ([2])

The Sustainable Innovation Early Phase Model

Tool [9]

References

- ↑ Konstantinou, Efrosyni, Jenny McArthur, Rob Leslie-Carter, and Vedran Zerjav, 2021. Climate Change and the Evolution of the Project Management Profession, Project Management Institute. (https://www.projectmanagement.com/contentPages/video.cfm?ID=736527&thisPageURL=/videos/736527/climate-change-and-the-evolution-of-the-project-management-profession#_=_)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Bocken, N. M. P., M. Farracho, R. Bosworth, and R. Kemp, 2014. The Front-End of Eco-Innovation for Eco-Innovative Small and Medium Sized Companies, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 31:43–57. Available at: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/245338/The-front-end-of-eco-innovation_final__open-access.pdf?sequence=1 )

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sherwin, Chris, 2017. The Fuzzy Front-End of Sustainability, Edie. (https://www.edie.net/the-fuzzy-front-end-of-sustainability/) )

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Figueiredo, João, N. Correia, I. Ruivo, and J. L. Alves. 2015. “A Cross-Functional Approach for the Fuzzy Front End: Highlights From a Conceptual Project.” in International Conference on Engineering Design ICED15. Milan, Italy. (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-CROSS-FUNCTIONAL-APPROACH-FOR-THE-FUZZY-FRONT-A-Figueiredo-Correia/717996dc452bfc56468287064373c468d8de282b)

- ↑ Morris, Peter W. G. 2017. Climate Change and What the Project Management Profession Should Be Doing about It - a UK Perspective. APM, UCL.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Olsson, Nils O. E., and Knut Samset. 2006. “Front-End Project Management, Flexibility, and Project Success.” in PMI® Research Conference: New Directions in Project Management, Montréal, Québec, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Cross, Nigel. 2000. Engineering Design Methods: Strategies for Product Design. 4th ed. John Wiley And Sons Ltd.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bason, Christian. 2023. “Embracing a New Leadership Role for the Future: Mission Managers.” Danish Design Center. Retrieved May 3, 2023 (https://ddc.dk/mission-managers/)

- ↑ Stock, Tim, Michael Obenaus, Amara Slaymaker, and Günther Seliger, 2017. A Model for the Development of Sustainable Innovations for the Early Phase of the Innovation Process, Procedia Manufacturing 8:215–22. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351978917300331?via%3Dihub