Integrating Mindfulness in Project and Program Management

Mindfulness is a state of consciousness in which attention is focused on present-moment phenomena occurring both externally and internally (Dane, 2011) [1]. This present-moment phenomena can also include embarking in creative imagination about the future, problem solving in the present or analysis of the past - as well as a discerning capacity of observing the present situation and context without falling into habitual tendencies or routines. This targets a number of challenges for Project and Program managers in where, due to time pressure, uncertainty and personal cognitive biases, sub-optimal decisions are often made highly impacting the projects outcomes.

This article intends to build upon the growing number of theories and evidences of the benefits of mindfulness, from two perspectives: individual and collective. It will draw from the latest research on the topic and link it to the existing framework for Mindfulness in High Reliability Organizations (HRO), developed by professors Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. Finally, the article will finish by suggesting potential tools and areas of integration for Project and Program Managers practice.

Contents |

Context

Historical definition of Mindfulness

The earlier account of the meaning of the world mindfulness comes from the Pali-term sati, simply meaning a state of non forgetfulness, bearing in mind a given object of attention. This includes retrospective memory of things in the past; prospective memory, to remember to do things in the future; and present centered recollection in the sense of maintaining attention to the present reality. [2]

In several contemplative traditions mindfulness this mental factor is viewed as a pre-requisite to: 1) Develop attention/concentration skills 2) Develop empathy and altruism; and 3) Developing cognitive balance. The latter can be generally understood as the self-awareness of our own internal mental processes, cognitive biases and tendencies, and the degree of freedom to which an individual can refrain from acting on them.[3]

Mindfulness in the West

Even though there are earlier accounts of Mindfulness in the West, the recent popularity of the concept of Mindfulness in the West is generally attributed to Jon Kabbat-Zinn and his work on Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programme. The adoption of mindfulness related practices/training has been widespread, ranging from training and development programs of major corporations from Google to General Mills, to programs in prisons to prevent work burnout of juvenile guards.

Universities, too, have taken up the call. For example, the director of mindfulness education at UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center leads on average 200 people every week in a silent Mindfulness Awareness meditation class held at the Hammer Museum’s Billy Wilder Theater [4]

Recent research

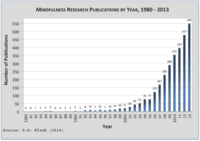

The past 30 years have seen exponential growth in research of Mindfulness. Much research concerned with the development of individual-level mindfulness maintains that mindfulness can be developed through meditation. The research takes its cue from Jon Kabat-Zinn's MBSR programme but also a variety of other Mindfulness Based Interventions (MBIs) i.e.: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy [5]

Building on the view that mindfulness is a byproduct of meditation experimental research has shown that state mindfulness can be activated through brief meditation-related instructions and exercises (e.g., Hafenbrack et al. 2014, Ostafin & Kassman 2012, Papies et al. 2012, Reb & Narayanan 2014).

The growth in mindfulness research literature from 1980-2013 is shown in the graph at the right-handside.

Individual Mindfulness

| Definitions | Source |

|---|---|

| A state of consciousness in which attention is focused on present-moment phenomena occurring both externally and internally | Dane (2011, p.1000) |

| A meta-cognitive ability defined as "a state of being attentive to and aware of what is taking place in the present" and involves conscious perception and processing of external stimuli (in contrast to automatic tendencies) | Eisenbeiss & van Knippenberg (2015) |

| A state of consciousness in which individuals pay attention to the present moment with an accepting and nonjudgemental attitude | Brown et al. 2007, Kabat-Zinn 1994 |

| An active state of mind characterised by a novel distinction-drawing that results in being (a) situated in the present, (b) sensitive to context and perspective, and (c) guided (but not governed) by rules and routines | Langer (2014, p. 11) |

Benefits of Individual Mindfulness

Different research on mindfulness has proved its varied impacts on health, performance and emotional regulation. Some of the key findings presented include:

- enhanced psychological and physical well-being (e.g. Brown et al. 2007)

- slow aging (Epel et al. 2009)

- improve standardised test performance (Mrazek et al. 2013).

- Research has demosntrated that meditative training programs reduce work-related stress (e.g., Bazarko et al. 2013, Wolever et al. 2012).

- Hulsheger et al. (2013) found through a field experiment with working professionals that mindfulness reduced emotional exhaustion and increased job satisfaction.

Even more relevant to our case in point, organisational research indicates that individual mindfulness is positively related to employee outcomes such as:

- Work engagement (Leroy et al. 2013) and

- Job performance (Dane & Brummel 2014).

Suggesting the mindfulness contributes to an organisation's bottom line.

In a study of nuclear power plant operations, Zhang et al. (2013) found that trait mindfulness was positively related to job performance for operators who held jobs high in task complexity (see also Zhang & Wu 2014, for relationships between trait mindfulness and safety performance in the same industry). Dane & Brummel (2014) found a positive relationship between workplace mindfulness and job performance among those working in a dynamic performance environment (the restaurant service industry) that remained significant when controlling for three dimensions of work engagement.

Furthermore, Reb et al. (2015) found positive relationships between work-related mindfulness and task performance and organizational citizenship behavior, respectively, within their survey of working adults. Also relevant to overall performance, Eisenbeiss & van Knippenberg (2015) found that employees high in trait mindfulness responded more strongly to ethical leadership in terms of the effort and helping behaviors they put forth. This suggests that, in the presence of an ethical leader, individuals high in trait mindfulness are more likely to perceive and embrace the values and behaviors they perceive in ethical leaders and to perform accordingly. Mirroring this finding, through a pair of cross-industry, survey-based studies, Reb et al. (2014) found that the trait mindfulness of supervisors is positively related to the well-being and performance of their employees.

These findings suggest that the mindfulness of one person in an organization can influence the well-being and performance of others and also that individual mindfulness practice can have an impact accross all levels of organization, ranging from strategic and tactical to operational.

Collective Mindfulness

Collective mindfulness was originally developed to explain how high-reliability organizations (HROs) avoid catastrophe and perform in a nearly error-free manner under trying conditions. Over time, the focus has expanded to include "organizations that pay close attention to what is going on around them, refusing to function on ‘auto-pilot’”. Collective mindfulness is a means of engaging in the everyday social processes of organizing that sustains attention on detailed comprehension of one’s context and on factors that interfere with such comprehension (Vogus & Sutcliffe 2012; Weick et al. 1999; Weick & Sutcliffe 2001, 2006, 2007).

Some of the most common definitions of Collective Mindfulness highly influenced by Weick et al work are the following:

| Definitions | Source |

|---|---|

| To stay mindful, despite hazardous environments, frontline employees consider constantly five principles: tracking small failures, resisting oversimplification, remaining sensitive to operations, maintaining capabilities for resilience, and taking advantage of shifting locations of expertise | Ausserhofer et al. (2013, p. 157) |

| Actively and continuously question assumptions; promote orderly challenge of operating routines and practices so successful lessons of the past do not become routine to the point of safety degradation; “outside view” actively solicited or created through active multidisciplinary review of the routine and debriefing of the unusual to prevent normalization of deviance | Knox et al. (1999, p. 26) |

| The combination of ongoing scrutiny of existing expectations based on newer experiences, willingness, and capacity to invent new expectations based on newer experiences, willingness and capacity to invent new expectations that make sense of unprecedented events, a more nuanced appreciation of context and ways to deal with it, and identification of new dimensions of context to improve foresight and current functioning | from Weick & Sutcliffe 2001, p. 42) |

| Mindfulness refers to processes that keep organizations sensitive to their environment, open and curious to new information, and able to effectively contain and manage unexpected events in a prompt and flexible fashion | Valorinta (2009, p. 964) |

Benefits of Collective Mindfulness

Investigation on the employee and organisational consequences of collective mindfulness - defined as the collective capability to discern discriminatory detail about emerging issues and to act swiftly in response to these details (Weick et al. 1999, 2000; Vogus & Sutcliffe 2012) - and, in doing so, have found an array of benefits. For employees,

- mindful organising is associated with lower turnover rates (Vogus et al. 2014a).

For organisations, collective mindfulness is positively related to salutary organisational outcomes including:

- more effective resource allocation (Wilson et al. 2011);

- greater innovation (Vogus % Melbourne 2003);

- improved quality, safety and reliability (e.g., Vogus & Sutcliffe 2007a,b).

Interestingly, these effects are most commonly observed in particularly trying contexts charactered by complexity, dynamism, and error intolerance. This suggests that some of these benefits can be achieved even in the toughest project and programs situations.

Why is it important? The Impact of Human Behaviour on Project and Program Management

Independent of the actual complexity of a project is the way we perceive and manage this complexity. Arguably, regardless of the project's "real” complexity, what count are our perception and reaction to it. (2015 J. Oehmen, C. Thuesen, P. Parraguez, and J. Geraldi)

We are incredibly adaptable at learning although our capacity to make decisions is limited by at least three main factors:

- Our access to information will never be perfect and completely and accurately represent the full current state;

- We have cognitive limitations—for example, regarding the number of factors we can consider in parallel, the amount of information we can take up, or the speed with which we can process it; and

- The time we have to make a decision.

Adding to these cognitive limitations, our subconscious or built-in decision-making models and routines, i.e.: cognitive biases and heuristics, can often be detrimental when trying to come up with optimal solutions/responses when managing complex systems. Below some of the key findings on these topics, and how they directly affect decision making at large and project/program management in particular:

Prospect Theory and Cognitive Biases

"Humans are not the rational beings they think themselves to be", argues Nobel lareaute Daniel Kahneman. In his book Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman unpacks his life-long research on prospect theory which, in a nutshell, addresses the idea that: the experimental faults in Daniel Bernoulli's traditional utility theory and challenging that economic rationality of Utilitarian theory do not reflect people's actual choices under risk, by not taking into account their cognitive biases.

Several key findings of his studies have been widely used in Economics, Finance and business (Andrei Shleifer, 2012). Some of these insights are on the frontier between behaviour economics and psychology and therefore it is the authors' perspective that they are also of utmost relevance for project and program management.

A non exhaustive list of relevant findings that are key to our discussion are shown bellow, illustrated with examples:

Framing

Framing is the context in which choices are presented. People tend to avoid risk when a positive frame is presented but seek risks when a negative frame is presented.

Example: Participants were asked to choose between two treatments for 600 people affected by a deadly disease. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, whereas treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die. This choice was then presented to participants either with positive framing, i.e. how many people would live, or with negative framing, i.e. how many people would die.

| Framing | Treatment A | Treatment B |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | "Saves 200 lives" | "A 33% chance of saving all 600 people, 66% possibility of saving no one." |

| Negative | "400 people will die" | "A 33% chance that no people will die, 66% probability that all 600 will die." |

Treatment A was chosen by 72% of participants when it was presented with positive framing ("saves 200 lives") dropping to only 22% when the same choice was presented with negative framing ("400 people will die").

Optimism bias and the Planning Fallacy

Kahneman explains a "pervasive optimistic bias", which "may well be the most significant of the cognitive biases". Associative memory leads us to respond fairly automatically to new stimulus by framing them on the network of experiences that we have been through before. The danger, however, is when the situation is in fact new and treating it merely like a previous situation might lead us to disregard important factors, details or new information that would require greater effort - or mindfulness - to apprehend and act upon. This leads to people having overconfidence in judgements that are not necessarily true.

When we find ourselves in front of a question that we can't answer, our internal instinctive process is to answer a similar easier question we had in the past and use this answer instead. People are often unaware of this substitution process and that it will use the right answer to the wrong question.

To explain overconfidence, Kahneman introduces the concept he labels What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI). This theory states that when the mind makes decisions, it deals primarily with Known Knowns, phenomena it has already observed. It rarely considers Known Unknowns, phenomena that it knows to be relevant but about which it has no information. Finally it appears oblivious to the possibility of Unknown Unknowns, unknown phenomena of unknown relevance.

In 2003, Lovallo and Kahneman proposed an expanded definition of the Planning Fallacy as the tendency to overestimate benefits and underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions, impelling people to take on risky projects. According to this definition, the planning fallacy results in not only time overruns, but also cost overruns and benefit shortfalls.

Some empirical studies support this:

- In a 1994 study, 37 psychology students were asked to estimate how long it would take to finish their senior theses. The average estimate was 33.9 days. They also estimated how long it would take "if everything went as well as it possibly could" (averaging 27.4 days) and "if everything went as poorly as it possibly could" (averaging 48.6 days). The average actual completion time was 55.5 days, with only about 30% of the students completing their thesis in the amount of time they predicted.

- In 2002, American kitchen remodeling was expected on average to cost $18,658, but actually cost $38,769 (Holt, Jim (27 November 2011).

Finally, Kahneman suggests that humans fail to take into account complexity and that their understanding of the world consists of a small and necessarily un-representative set of observations. Furthermore, the mind generally does not account for the role of chance and therefore falsely assumes that a future event will mirror a past event.

One of the most emblematic real world examples:

The Sydney Opera House was expected to be completed in 1963. A scaled-down version opened in 1973, a decade later. The original cost was estimated at $7 million, but its delayed completion led to a cost of $102 million.

Sunk Cost or Escalation of Commitment

Escalation of commitment refers to a pattern of behavior in which an individual or group will continue to rationalize their decisions, actions, and investments when faced with increasingly negative outcomes rather than alter their course. The related sunk cost fallacy has been used by economists and behavioral scientists to describe the phenomenon where people justify increased investment of money, time, lives, etc. in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment ("sunk costs"), despite new evidence suggesting that the cost, beginning immediately, of continuing the decision outweighs the expected benefit.

Two famous cases include:

- The Big Dig in Boston

- Sony's continued participation in electronics after $8.5 billion in losses over 10 years

These and other key cases are reviewed and analysed; and the issue of Escalation of commitment is addressed in the two following papers:

- Stray, Viktoria Gulliksen; Moe, Nils Brede; Dybå, Tore (2012). "Escalation of Commitment: A Longitudinal Case Study of Daily Meetings"

- Woods, Jeremy A.; Dalziel, Thomas; Barton, Sidney L. (2012). "Escalation of commitment in private family businesses: The influence of outside board members"

Applications and practice

Individual Mindfulness

Collective Mindfulness: Lessons from High Resilience Organizations (HRO)

Weick and Sutcliffe have developed five principles that harness the key characteristics of collective mindfulness within an organization. These guidelines/principles apply upward from a strategic to tactical level of an organization as well as downwards to operational teams, crews and team leaders.

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Preoccupation with failure | A preoccupation with failure focuses the organization to convert small errors and failures into organizational learnings and improvements. |

| Reluctance to simplify | Simplify mindfully and reluctantly. Have in mind that simplification can become too simple resulting in useless, unprecise simplifications e.g. explanations and categories. Problems faced in complex projects typically offer several options and a nuanced picture to fully understand the best solution. |

| Sensitivity to operations | An organization must have an integrated overall and aligned picture of operation. Sensitivity to operations is closely related to sensitivity to relationships. Meaning a clear and unprejudiced communication between operation and management is crucial to understand the big picture. |

| Commitment to resilience | Accommodate unexpected events and react to them quickly as they arise. |

| Deference to expertise (Collective mindfulness) | Deference to expertise is about involving experts in the decision-making. The experts actively involved in the projects are more capable to give articulate solutions to problems. Rigid hierarchies have their own special vulnerability to error where errors at high levels tend to pick up and combine errors at low levels. HRO’s push decision making down where decision is made on the front line. The authority migrate to the people with the most expertise, regardless of their rank. Collective mindfulness is associated with cultures and structures that promote open discussions of errors, mistakes and awareness. |

Whenever people change the way they perceive the world they essentially rework the way they label and categorize what they see. This change in perception can be described with the following process:

- Re-examine discarded information

- Monitor how categories affect expectations and,

- Remove out-dated distinctions

Firstly, to rework one’s categories mindfully implies to evaluate how much information is discarded with a categorization of an instance with similar characteristics. Generally categorization help gaining control in a fast pace world. Categories can predict what will happen and plan one’s own actions. Without categories, any person or situation would be unique and therefore conserve scarce mental resources of attention and thinking. One category cannot describe all facets of a person and the professor must be aware of the discarded information within each category.

Secondly, mindful reworking of categories also mean that one pay close attention to their effect on the expectations. Categories and expectations are closely related. E.g., a person categorized as an expert is expected to know the answers within his/her field of expertise. These expectations constantly have to be revised and evaluated. It may be necessary to differentiate the expectations, replace them, supplement them, or discard the whole category.

Third, mindful reworking means a check whether the categories remain plausible. Outdated categorization with implausible distinctions of expectations ensure trouble. This is the basic misreading in HRO’s. The trouble starts when you fail to notice that you only look for whatever confirms your categories and expectations. “Believing is seeing. You see what you expect to see. You see what you have the labels to see. You see what you have the skills to manage.” (Weick, K. E. and Sutcliffe, K. M. 2001.) People who have a critical approach towards their categories by refining them, updating or replacing them notice more and catch unexpected events earlier in their development.

The case for Mindfulness in Project and Program Management

Projects never go according to plan. Far too many cases could be drawn to support this statement. That is why it is fundamental for project managers to be able to navigate in changing environments - making the best decisions not only as a way to accomplish the initial plans but also to seize the opportunities that manifest along the way.

Taking the example a recent interview with the Bispebjerg hospital Executive VP, he states: when managing a project with such a long life cycle (10y) there must be a continuous capacity to adapt because of the of the opportunities that make themselves present along the way. "What was a the best technology in the beginning of the project might be mediocre by the end of it" - this implies that if we firmly grasp onto our habitual ways of viewing and solving problems, refusing to absorb new information and reconstruct our way of thinking, we become blind to new opportunities presented by our context.

The mere awareness of our own limitations, can help us a great deal in understanding where it is that we need to introduce individual or collective mindful practice in order to not compromise decision making. As J. Oehmen, C. Thuesen, P. Parraguez, and J. Geraldi suggest: "While we cannot completely dissolve our cognitive limitations, we can discipline our minds by becoming aware of our “irrationalities” and inspiring ourselves to act in a mindful manner. Our behaviour will become more like we thought it was anyway—rational and fact-based."

Already mentioned above, collective mindfulness refers to processes that keep organizations sensitive to their environment, open and curious to new information, and able to effectively contain and manage unexpected events in a prompt and flexible fashion. If this sounds particularly similar to the job description for a Program Manager, it's because it is. Taking the Programme London Olympics 2012 as an example, part of the success of its management was due to a heightened awareness of the potential synergies to be drawn amongst the several individual projects - and how could these mutually reinforce one another in reaching the ODA's priority goals. (revisitar os papers dados na aula)

Apart from all the objective metrics and targets used to project and program efficient delivery; the human aspect, including from work satisfaction, social relations and individual well-being are also a key factor that should be accounted for when considering the beneficial impacts of integrating mindfulness in Project Program and Portfolio Management. In short, even though there are positive outcomes in terms of organizationals performance, a key point is that the benefits of fostering an environment with such a mindset will produce benefits for each individual that will never be captured in its entirety.

Of course there also are limitations to this, most of which have to do with the complexity of the organizations and the necessity for individually adapt such approaches to each context. Also, the fact the breadth of this topic makes it difficult for researchers to come with validly and unequivocal findings about the benefits of such practices and approaches within an organization. Finally, these practices are not a substitute for competent leadership and management skills and are only to be viewed as a complement in order to increase quality and performance.

It remains your call to decide which stance would you like you and organisation to hold on this topic. Would you rather wait for all the data come in before embracing a Mindful culture in your oganisation; or given what is already out there are you willing to try it out and see how well your Project and Program Management can improve. How are you going to manage this risk?

Annotated Bibliography

Mindfulness in Organizations: A Cross-Level Review Kathleen M. Sutcliffe,1 Timothy J. Vogus,2 and Erik Dane

The Attention Revolution

Weick

Josef

References

- ↑ Dane E. 2011. Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in the workplace. J. Manag. 37:997–1018

- ↑ B. Alan Wallace, "The Attention Revolution"

- ↑ B. Alan Wallace, "The Four Applications of Mindfulness"

- ↑ Hanc J. 2015. 25 minutes of silence in the City of Angels. The New York Times, March 20, F2

- ↑ Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, Lau MA. 2000. Prevention of re-lapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68:615–23