Balanced Scorecard in Project Portfolio Management

Contents |

Abstract

The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is a strategic planning and management system that organizations use to connect the strategy elements such as vision, mission and core values with more operational elements such as objectives, measures and targets.

It was introduced by Robert S. Kaplan in 1992 (“The Balanced Scorecard – Measures that drive performance”, Harvard Business Review) after observing that managers focused their attention only on aspects of performance that were measurable, with the primary measurement system in most organizations being based on financial accounting. In their view, these financial reporting systems fail to measure or provide a basis for managing the value created by the organization’s intangible assets.

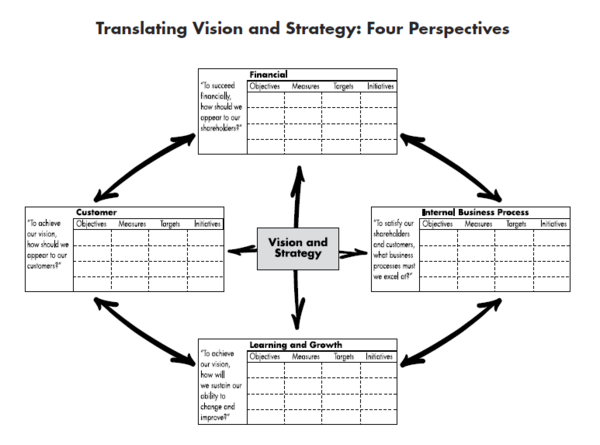

In order to connect the daily work practices with the strategic goals of a company, the Scorecard approach enables managers to review performance from four different perspectives: Financial perspective, Customer perspective, Internal Process perspective, and Learning and Growth perspective.

Nowadays, BSCs are used extensively in business and industry, government, and nonprofit organizations worldwide. BSC has been selected by the editors of Harvard Business Review as one of the most influential business ideas of the past 75 years and was listed fifth among the top ten most widely used management tools around the world in a recent global study by Bain & Co. [1]

The Idea behind the Method

Robert S. Kaplan observed that, as companies around the world transform themselves for competition that is based on information, their ability to exploit intangible assets has become far more decisive than their ability to invest in and manage physical aspects. (reference, usage)

Based on this observation, Kaplan introduced the Balanced Scorecard. The latter augments traditional financial measures with benchmarks for performance in three key nonfinancial areas: a company’s relationship with its clients, its key internal processes, and its learning and growing. “When performance measures for these areas are added to the financial metrics, the result is not only a broader perspective on the company’s health and activities, it is a powerful, organizing framework. A sophisticated instrument panel for coordinating and fine-tuning a company’s operations and businesses, so that all activities are aligned with its strategy.”(1, Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System)

Therefore, BSC enables companies to track financial results while simultaneously monitoring progress in building the capabilities and acquiring the intangible assets they would need for future growth. In other words, it is not a replacement for financial measures but rather their complement.

Translating Vision into The Four Perspectives

The BSC translates an organization’s vision into a set of performance indicators distributed among four perspectives: Financial, Customer, Internal Business Processes, and Learning and Growth.

The four perspectives:

The financial perspective: Focuses on financial performance of an organization and it mainly covers the revenue and profit targets as well as the budget and cost-saving targets. It is important to note that financial performance is usually the result of good performance in the other three scorecard perspectives.

The customer perspective: Focuses on performance targets as they relate to customers and the market. It usually covers customer growth and service targets as well as market share and branding objectives. Typical measures and KPIs in this perspective include customer satisfaction, service levels, net promoter scores, market share and brand awareness.

The internal process perspective: Focuses on internal operational goals and covers objectives as they relate to the key processes necessary to deliver the customer objectives. At this perspective, companies outline the internal business processes goals and the activities the organization has to do really well internally in order to push performance. Typical example measures and KPIs include process improvements, quality optimization and capacity utilization.

The learning and growth perspective: Focuses on the intangible drivers of future and is often broken down into the following components:

• Human Capital (skills, talent, and knowledge)'

• Information Capital (databases, information systems, networks, and technology infrastructure)

• Organization Capital (culture, leadership, employee alignment, teamwork and knowledge management).

The performance measurements:

Objectives: Are the short- and long-term tangible strategic objectives derived from an organization's vision and strategy. Some organizations attempt to decompose the high-level strategic objectives of the business unit scorecard into specific objectives at the operational level. For example, an on-time delivery (OTD) objective on the business unit scorecard can be translated into an objective to reduce setup times at a specific machine, or to a local goal for rapid transfer of orders from one process to the next.

Measures: The measures are financial and nonfinancial and are balanced between the “outcome measures (lag indicators)” the final results from past efforts: Return on equity, customer retention, new product revenue, etc., and the “performance drivers (lead indicators)” that drive future performance: satisfaction survey, product development cycle, revenue mix, etc.

Targets: The targets refer to the scorecard measures that, if achieved, will transform the company. The targets should represent a discontinuity in business unit performance: doubling the return on invested capital, or a 150 percent increase in sales during the next five years, etc.

Initiatives: Are the actions (projects) an organizations puts in place in the attempt to transform themselves to compete successfully in the future, these initiatives must be aligned with what stated in the BSC.

The Balanced Scorecard in Project Portfolio Management (PPM)

PPM aligned to Organization’s Strategy:

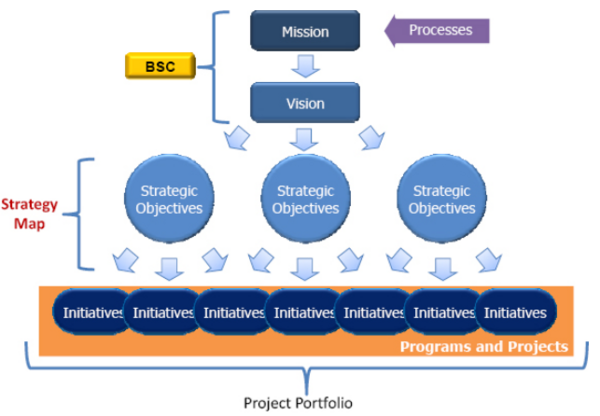

One of the main issues when selecting the projects to be executed as part of the organization's portfolio is if the project is aligned to the organization's strategic objectives. If this is not the case, there is a valid chance the organization and its stakeholders will not get a proper return on their investment. The project portfolio is defined as a collection of projects and/or programs and other related work, grouped to facilitate effective management of that work to meet strategic business objectives. Within the organizational context, PPM establishes the proper actions to accomplish strategic goals and objectives which means that it requires direct inputs from the strategic planning.

Strategic Planning:

Strategic planning is the process whereby the organization's vision and mission, plus the approach that will be adopted to achieving them during a certain period of time, are established by upper management. This process continues with the establishment of strategic objectives and goals, which are the intended achievements of the organization in terms of business results, interpreted from various perspectives—financial, customer, infrastructures, products and services, or by cultural outcomes. All this information is set into a strategic document termed “Strategic Plan.”

BSC bridges PPM with Strategic Planning:

In order to place all the initiatives proposed during the Strategic Planning process, the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is applied. What matters most from the perspective of project portfolio management is that the BSC provides a record of the strategic initiatives that are the strategic projects to be, and from there it is possible to start analyzing, evaluating, prioritizing, planning, and depending on the case, executing the projects that will make the mission and vision of the organization something tangible (Kaplan & Norton, 2008). Figure 3 shows how this “strategic leap” happens. Processes and other sources affect the organization's mission and vision; they provide guidance in deciding the types of initiatives (strategic initiatives) that will likely succeed in accomplishing that mission and that vision for the organization. Those initiatives are translated into projects and programs, most likely embedded into a project portfolio where proper management for effective performance and results delivery is performed (Kaplan & Norton, 2000; Kaplan & Norton, 2008; PMI, 2008a, p. 8; PMI, 2008b, p. 10).

The BSC Implementation Steps

The steps to implement BSC towards an effective PPM which aligns to the organization’s strategy can be summarized involved as follows:

1.Preparation

The organization must first define the business unit for which a top-level scorecard is appropriate. In general, a scorecard is appropriate for a business unit that has its own customers, distribution channels, production facilities, and financial performance measures.

2. Interviews: First Round

Each senior manager in the business unit—typically between 6 and 12 executives—receives background material on the balanced scorecard as well as internal documents that describe the company's vision, mission, and strategy. The balanced scorecard facilitator conducts interviews with the senior managers to obtain their input on the company's strategic objectives and tentative proposals for balanced scorecard measures.

3. Executive Workshop: First Round

The top management team is brought together with the facilitator to undergo the process of developing the scorecard. During the workshop, the group debates the proposed mission and strategy statements until a consensus is reached. The group then defines the key success factors: “If I succeed with my vision and strategy, how will my performance differ for shareholders; for customers; for internal business processes; for my ability to innovate, grow, and improve?” After defining the key success factors, the group formulates a preliminary balanced scorecard containing operational measures for the strategic objectives.

4. Interviews: Second Round

The facilitator reviews, consolidates, and documents the output from the executive workshop and interviews each senior executive about the tentative balanced scorecard.

5. Executive Workshop: Second Round

A second workshop, involving the senior management team, their direct subordinates, and a larger number of middle managers, debates the organization's vision, strategy statements, and the tentative scorecard. At the end of the workshop, participants are asked to formulate stretch objectives for each of the proposed measures, including targeted rates of improvement.

6. Executive Workshop: Third Round

The senior executive team meets to come to a final consensus on the vision, objectives, and measurements developed in the first two workshops; to develop stretch targets for each measure on the scorecard; and to identify preliminary action programs to achieve the targets. The team must agree on an implementation program, including communicating the scorecard to employees, integrating the scorecard into a management philosophy, and developing an information system to support the scorecard.

7. Implementation

A newly formed team develops an implementation plan for the scorecard, including linking the measures to databases and information systems, communicating the balanced scorecard throughout the organization, and encouraging and facilitating the development of second-level metrics for decentralized units.

8. Periodic Reviews

Each quarter or month, a blue book of information on the balanced scorecard measures is prepared for both top management review and discussion with managers of decentralized divisions and departments. The balanced scorecard metrics are revisited annually as part of the strategic

Limitations

In practice, despite widespread use and practitioner-oriented literature suggesting the BSC has beneficial values especially in enhancing organizational performance and strategy achievement, a large body of academics is skeptical about the relationship between BSC and organizational outcomes. In fact, a leading criticism asserts the widespread practice of the BSC in itself does not demonstrate the BSC is beneficial to organizations (Kraaijenbrink, 2012). In support of this assertion, BizShifts (2010) espouse that, within a decade of its inception, an estimated 44% of organizations worldwide had implemented the BSC; however, only 22% to 50% of these organizations achieved higher return on asset and higher return on equity while an estimated 85% of the organizations experienced problems during implementation. Based to academics, the problems can be related to:

1. Rigidity

Voelpel et al. (2005) observe rigidity in the conception of the BSC as a performance measurement tool. While Kaplan and Norton (1992), and Casey and Peck (2004) contend performance measurement is a significant benefit of the BSC, Voelpel et al. (2005) agree and disagree. The BSC enables an organization to transform strategy into tangible performance measures but by limiting performance measures to four categories and this fact introduces rigidity. Rigidity is evident when the four performance measurement categories form the basis of defining key success factors. The BSC thus forces managers to put success indicators into one of the four categories. The result is the BSC limits the view of an organization by leaving no room for cross-perspectives that have combined effect on strategy execution. Further, there is the danger of an organization neglecting success indicators that do not fall into any of the four categories.

2. Confirmation Bias

The four categories also risk creating confirmation bias, a situation where managers only take interest in what they want to measures but ignore changes in the external business environment as evident in the case of Encyclopedia Britannica, which almost went out of business because of sticking to its once successful success factors.

3. Complexity & resource intensive nature

The final limitation in the practice of the BSC is the complexity and resource intensive nature of its implementation. According to Antonsen (2010), implementing the BSC requires an organization to gather new data, which could create work overload for some departments. It could potentially lead to employee resistance and cynicism as well as to managerial resistance due to increased availability of information with the potential to upset the current power balance.

4. Limitations in Learning & Growth

Rillo (2004) observes the limitation of the BSC in dealing with knowledge creation, learning and growth. Although the BSC has a learning and growth perspective that deals with knowledge creation and innovation, the perspective adopts the traditional logic of innovation, where research and development (R&D) deals with innovation but conceals both the process and the innovation itself from competitors. The only difference is the BSC extends the innovation concept from R&D to the entire organization. However, the traditional logic of innovation is changing from closed to open innovation influenced by increasingly inter-linked and networked nature of today’s businesses. In fact, in the present knowledge economy increased mobility of knowledge workers, advancement in information and communication technology, and improved accessibility to venture capital places a greater emphasis on the open nature of innovation. The practice of the BSC does not take into account the changing nature of innovation and does not provide for performance measures and interlink ages with external partners in developing innovative ideas and products and the implementation of the innovative ideas. The limitation of the BSC is therefore to include and to measures distributed innovation in a highly interlinked and networked market.

5. Insufficiency in describing the business complexity

BizShifts (2010) claims that BSC is becoming increasingly deficient since one-way linear cause-and-effect relationships are insufficient to describe the complex nature of today’s business. For instance, customer perspective is inter-linked with various perspectives such as employee satisfaction, delivery time and product quality. In turn, customer satisfaction could influence employee satisfaction. Thus, the complex and interlinking nature of the business process suggests the way the success indicators are linked in the BSC requires revision to consider the entire system rather than the direct and visible success factors alone.

Annotated Bibliography

'“The Balanced Scorecard”', Robert S. Kaplan and Dapid P. Norton (1996), Harvard Business School Press'

It is the original book written by Kaplan and Norton, in which the authors explain the Balanced Scorecard approach as well as providing examples of application.

'“Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System”', Robert S. Kaplan and Dapid P. Norton (2007), Harvard Business Review

It is an article by Kaplan and Norton that provides information on how to use the tool in a contemporary organization.

'Balanced Scorecard: A New Tool for Performance Evaluation',Arman Poureisa, Mohaddeseh Bolouki Asli Ahmadgourabi and Ako Efteghar (2013), Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business (IJCRB)

It is a paper which reviews how BSC emerged and developed during the years.

'A Critique of the Balanced Scorecard as a Performance Measurement Tool', Emad A. Awadallah and Amir Allam (2015), International Journal of Business and Social Science

The main aim of this paper is to provide a review and critique of the BSC as a performance measurement tool and debating whether the BSC is in fact a universal solution for corporate performance measurement.

www.balancedscorecard.org/

It is the official site of the Balance Scorecard Institute (BSI) and provides basic information and consulting services regarding the BSC approach.

References

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameda