Dealing with conflict in project management

Abstract

It is of interest for the project manager to deliver a high-quality result on time and on budget. No projects are executed without conflicts and they have the potential to derail a project completely if ignored or improperly managed e.g. via loss of profit, time, quality, creativity or morale. On the other hand, proper conflict management can lead to positive change such as improved respect and understanding for one another. The competent project manager should therefore possess knowledge that allows him or her to identify and classify a conflict, resolve a conflict accordingly, and design a working environment that minimizes the risk of conflicts occurring. A conflict is spawned from multiple variables such as interpersonal relations, stress, or the difficulty of the task at hand. As a consequence of the complexity, no best practice exists. A strategy for resolving conflict may be applicable in one scenario, but useless or even damaging in another. The project manager must be able to analyze the situation and chose the correct approach to conflict management based on the information he or she has available. In doing so, a fundamental understanding of human psychology and Cross-cultural Management is a plus.

Definition

Conflict is a state of discord caused by the actual or perceived opposition of needs, values and interests. Conflict as a concept can help explain many aspects of social life and social death such as social disagreement, conflicts of interests, and fight between individuals, groups, or organizations. A conflict can be internal (within oneself) or external (between two or more individuals). Without proper social arrangement or resolution, conflicts in social settings can result in stress or tension among stakeholders.[1]

Looking from a project management perspective, conflicts can be internal e.g. interpersonal conflicts or between groups e.g. if two project groups both claim utilization of scarce resources. This article focuses on the former example, as that is a more typical scenario for the project manager. The latter dispute will often move upwards the organizational hierarchy.[2] When dealing with the latter type of conflict, Pondy’s Model of Organizational Conflict provides a framework for assessing and acting accordingly to the type of conflict.[2]

Why focus on conflicts?

In short, one should manage conflicts to avoid their negative influence and to ensure their positive effects. Project members, including the project manager, might be tempted to shy away from conflict in the fear of dissociation, being wrong, hostility, breaking up interpersonal relationships, etc.[3] This is ill-advised as conflicts that are not resolved tend to snowball or escalate cf. the conflict stages below. This means that the sooner the problem is addressed, the better. Table 1 shows what a project manager might experience if a conflict is looming, and what can be gained from properly solving the conflict:[3]

| Signs of conflict looming | Advantages of conflict resolution |

|---|---|

| Productivity drops off | Intimacy |

| Quality deteriorates | Respect and understanding |

| Sick leave increases | Appreciation |

| Employees quit | A better working environment |

| Bad mood | Positive example for future reference |

| Unease and irritation in the work place | Others realize that you are right |

| Sleep deprivation among the employees | Time and energy |

Reasons for conflicts occuring

Conflicts are the product of countless variables. A seemingly insignificant event will affect the mood and behavior of people on a subconscious level. For instance, teachers grading papers have been shown to give statistical significantly higher grades immediately after eating lunch, as they happen to be in a better mood.[4] Similarly, this is why a formula for the birth of conflicts does not exist. There are too many factors. Even though it is impossible to articulate the reason for a conflict prior to its occurrence, some areas tend to spew more conflicts than others. By knowing and understanding these areas, the project manager can identify and thereby solve conflicts faster. Studies have shown the following points to lead to the most conflicts: [5]

- Unresolved disagreement that escalated to an emotional level

- Poor organizational structure

- Personality clashes / differences in values and goals

- Poor communication / miscommunication

- Lack of cordial relationships between labor and management.

The project manager should be particularly alert regarding the potential for conflict if the project work starts venturing into these areas.

Dimensions of conflict

Conflicts in a project-setting can be divided into one of four basic dimensions.[6] It is noteworthy that in a real-life setting, a conflict can easily be the sum of different dimensions. Nonetheless, it is valuable to understand the different dimensions, as they have different levels of severity and should be tackled in different manners.

- Instrumental dimensions

- Dimensions of interest

- Dimensions of value

- Personal dimensions

Instrumental dimensions occur when disagreeing about objective and methods i.e. what should be done, and how should it be done? Here, parties might disagree and must come up with a solution. These conflicts often occur and can lead to creative decision making. Due to their normality, they rarely lead to animosity. The approach to this type of conflict is problem solving with the purpose of finding a solution.

Dimensions of interest occur when competing for resources. This can happen between project teams e.g. competing for machinery or internally in a project team e.g. competing for space in the project room. The approach to this conflict should be negotiation to come up with an agreement that settles the dispute.

Dimensions of value occur when values of the parties are at stake, which the parties are willing to stand up for. Examples include religion or political belief. This type of conflict is seldom related to the project and has a high potential for creating emotional response and a negative impact on the project. As we cannot negotiate our beliefs, dialogue with the purpose of mutual understanding is the goal here.

The personal dimension is the type of conflict that hits the involved people the hardest and has the most potential for disrupting the project-work. Again, dialogue and mutual understanding is the end-goal here to create a better and healthier atmosphere.

Conflict stages

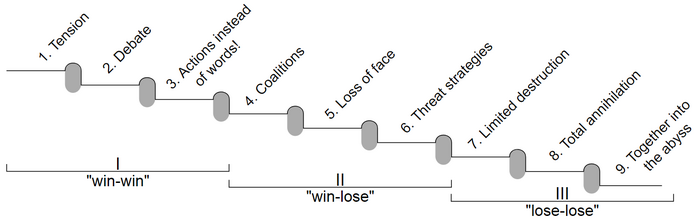

Recall that conflict can lead to positive change if managed correctly. It is very much a case of identifying and dealing with the conflict in an early stage. In doing so, the conflict escalation model can be applied. The model, developed by Australian conflict expert Friedrich Glasl, states that all conflicts will move through some general steps, each with its own dynamics, figure 1:

A brief explanation of the stages are:

Stage 1: Tension

- Tensions exist. It can be any of the four dimensions of conflict. Tensions often occurs and may perhaps not even be noticed.

Stage 2: Debate

- A debate occurs, where one party tries convincing another party that his or her take on the subject is correct.

Stage 3: Actions instead of words

- Pressure rises without resolving the conflict, which manifests to actions. Such actions could be starting to ignore each other or talking badly about the other party.

Stage 4: Coalitions

- One party starts looking for sympathizers, that share his or her position, in order to win the conflict. The argument starts expanding from the initial subject of the dispute. From here on, the major interest is that the opponent loses.

Stage 5: Loss of face

- The desire for winning starts erasing the moral principles of the actors. The thought of the opponent losing face is attractive.

Stage 6: Threat strategies

- The actors try to establish control of the situation by threatening the opponent with various demands. Typically, these ultimatums have the opposite effect.

Stage 7: Limited destruction

- The opponents sensitively try harming each other. From here on, the party disregards the damage that their own actions infect upon them.

Stage 8: Total annihilation

- The actions are now more destructive and the severity increases. The actors can no longer stop or control the escalation.

Stage 9: Together into the abyss

- One continues to attack the opponent, knowing that it also leads to the destruction of him or herself.

The three classes win-win, win-lose, and lose-lose represent the acceptable outcome of the conflict through the eyes of the person amidst the conflict. That is, in the first stage the actor wants to come to a solution that satisfies all parts. In the second stage, it is not only about winning; it is also about the other party losing. In the third stage, the individual is willing to sacrifice himself to see the opponent lose. A project manager's level of involvement and decisiveness should increase as a conflict progresses through the stages. A conflict moves from potentially yielding a positive outcome, to leading to a negative outcome when the parties move from win-win to win-lose.

If a conflict is in stage two and a project manager chooses to force a decision to stop the conflict, he or she removes the chance of reaping the benefits of proper conflict solution. Further, the project team might be frustrated that they are being monitored and limited. Oppositely, if a conflict is in stage 7, and a project manager chooses to avoid or accommodate the conflict, the PM becomes a hostage of the conflict and can only watch as the project deteriorates.

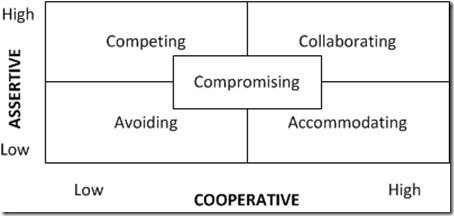

Conflict management styles

Whenever a conflict is looming in a project, the project manager is faced with a choice regarding how to address the conflict. To illustrate this dynamic, the Conflict Mode Instrument developed by Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann can be applied. A good project manager must understand in what instances the different styles are applicable.[8]

The cooperative axis speaks addresses to what extent the other party’s goal is achieved, while the assertive axis states whether one’s individual goals are achieved. The table below[3] highlights some scenarios where the different styles of management can be used, and some scenarios where the project manager should steer clear of them.

| Conflict style inventories | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Forcing/competing | When decisive action is needed

When unpopular and determined actions must be taken |

May destroy inter-personal relations when fulfilling own goals on

someone else’s account |

| Collaborating | When important decisions with long-term effects are to be taken | Often time-consuming, thus not suitable for trivial problems |

| Compromising | Good if pressed for time | May lead to two somewhat discontented parties |

| Avoiding | Postpone a conflict until emotions have cooled off.

When dealing with trivial problems and more important issues should have priority |

The conflict is not resolved |

| Accomodating | When collaboration is more important than the reason for conflict.

When the problem is more important for the other part |

Accommodation may deprive respect.

When important issues are at stake |

Relating to Friedrich Glasl and his conflict stages, one must understand that the cooperativeness falls and assertiveness rises, whenever a conflict is escalating to a stage, where it has profound negative impact on the project.

Conflict resolution

When it comes to resolving a conflict, the Conflict Mode Instrument provides an indication of the style of management that is best to apply. However, the tool does not shed light on the means of coming to a solution. For that, three broad approaches can be laid out.

- 1. Monitoring

- An accommodating approach. The project manager ensures the involved parties take action on the conflict to work it out. This method has the biggest potential for creating a positive, lasting result. Due to the low level of involvement from the project manager, it is best applied when a conflict is in its first three stages.

- 2. Mediating

- A compromise approach. Here, the project manager or an external conflict mediator is involved to help the parties with solving the dispute. The project manager must find a balance between intervening too soon, or alternatively not acting at all. This approach is best applied once the conflict hits the win-lose stage, or if the project manager assesses, that a conflict is on collision course towards that area. For instance, the PM should be particularly alert if the conflict is related to dimensions of value or personal dimensions.The key to the mediation process is making the parties understand each others point of view instead of trying to convince each other that their opinion is wrong. In doing so, communication and openness is key. The following questions provide a solid foundation for understanding each other and generating a compromise:

- What has happened?

- What do you feel?

- What do you want to happen now?

- A realistic solution is drafted based on the information along with a course of action to solve the dispute. When monitoring the communication, one has to understand what constitutes constructive and destructive communication. The project manager or mediator should strive for the parties trying to learn from each other, expressing their own concerns and needs, listening to the other party, attacking the problem, and sticking to the facts. Destructive communication is the polar opposite e.g. trying to win, blaming the other, interrupting, ignoring, or generalizing. No compromise will be made with such communication, and it should therefore be eliminated.

- A compromise approach. Here, the project manager or an external conflict mediator is involved to help the parties with solving the dispute. The project manager must find a balance between intervening too soon, or alternatively not acting at all. This approach is best applied once the conflict hits the win-lose stage, or if the project manager assesses, that a conflict is on collision course towards that area. For instance, the PM should be particularly alert if the conflict is related to dimensions of value or personal dimensions.The key to the mediation process is making the parties understand each others point of view instead of trying to convince each other that their opinion is wrong. In doing so, communication and openness is key. The following questions provide a solid foundation for understanding each other and generating a compromise:

- 3. Convicting

- A forced approach. The project manager or sponsor makes an executive decision e.g. one party leaves the project. This approach should be chosen as a last resort i.e. when the other approaches do not work - thereby the project manager should seldom convict without attempting to mediate. The exception would be if pressured by other forces such as time or executive management.

Character traits and conflict

A competent conflict manager needs to have a broad understanding of different ways people behave when facing a conflict. It is not a case of labeling or defining people, but more so of recognizing personality traits and adjusting the professional communication accordingly.[REF] Multiple tools and tests exist for understanding personalities. Noteworthy examples are Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)[9], The Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF)[10], and DISC assessment[11]. Despite different classification methods of the tools, their underlying indicators are based on attributes and a score, where an individual is placed somewhere on a spectrum. High scores in an attribute is associated with certain behavioral patterns, and the same goes for low scores.

A lot of these attributes can be directly linked to conflict - what can cause certain personality archetypes to become irritated, how a behavioral pattern responds in a conflict situation and so on. These things can be kept in mind when designing a project team. In doing so, one should strive to find a level of equilibrium in the team. That is, a well-rounded team will each be able to find a role in the project team and compliment each other's strengths and weaknesses. Alternatively, a project team designed with an abundance of a particular character trait may experience a harder time collaborating. A classical example would be having too many assertive or dominant individuals in a group. This is why Belbin's team roles or similar tools are commonly used to create well-rounded project teams.

Different personality tests use different attributes to define their classes. However, some common denominators exists. A brief explanation will be given of dominance, extroversion, urgency, and detail orientation as these are commonly found. Furthermore, examples will show how these character traits may be annoyed.

- Dominance

- Denotes the drive to exert influence over people and events. A high score is connected to an independent and assertive individual with a strong competitive drive. Dominating people may become frustrated if their needs are not fulfilled and if they do not get credit for their performance vis-à-vis why several dominating individuals with conflicting opinions can lead to conflict.

- On the other side of the spectrum, a low level of dominance is an agreeable and cooperative person. These people are risk averse, meaning that they prefer accommodating or collaborating. In a conflict-setting, one has to watch that these people do not allow the project to move in a sub-par direction for the sake of avoiding confrontation.

- Extroversion

- Extrovert people tend to be outgoing, optimistic, and socially poised. An extrovert person is interested in earning recognition, which often occurs through the success of a given project in the professional setting. Therefore, when faced with difficulties and setbacks in a project, the extrovert person might become severely frustrated. Moreover, extrovert people may talk before thinking, which can lead to interpersonal or value-related clinches.

- The introvert person is more serious, reflective, and cautious. Introverts may perceive extroverts as disruptive. If the difference is too big, that alone can lead to conflicts.

- Urgency

- Intensity of a persons tension and drive. Urgent people are classified as impatient, action oriented, and fast paced. Asking for the other actors point of view might seem like a waste of time, which is why a conflict can quickly escalate to the win-lose area.

- Low-scoring urgency is when people prefer a patient, stable, and calm environment. Just like with extroversion, if people are too far apart in this spectrum, it is difficult to accommodate both parties, and conflict may arise.

- Detail orientation

- Drive to conform to formal rules and structures. This is a factor that can be influenced by culture[12]. A high score indicates a precise, cautious individual with an attention to details. Two detail oriented people may have a hard time negotiating with each other due to their pride and righteousness.

- The opposite behavior is being informal, tolerant of risks and undaunted when criticized.

Minimizing conflict as the project manager

Recall that it is impossible to avoid conflicts altogether in any project-setting. However, it is possible for the project manager to minimize the risk of severe conflicts occurring. A common cause of conflict is dissatisfaction with the organizational structure from the workers point of view[5]. Even though it is not something that the project manager may decide, he or she should still identify its potential for issues.

If a company applies a matrix organizational structure, employees become so-called two-boss employees, as they answer both to the functional manager and product team manager.[2] This structure can lead to a dimensions of interest conflict, where different managers compete for claiming resources and attention to their projects. Ideally, this type of conflict is solved in a logical manner via tools such as critical path analysis and multi-project resource scheduling. If a settlement cannot be made, support from higher-level management can be called upon[13].

The project plan is drafted to provide structure and to create an overview of a given project. A detailed and accurate project plan creates the basis for constructive communication in the project-setting. This can prevent conflicts occurring in relation to the scope of the project and who is in charge of a task. Moreover, a realistic project plan has a feasible time and resource allocation for the team. By not stressing the team, the team members will be more in control of their feelings and the way that they communicate. The Critical Path Method in project planning is one tool that can be implemented to minimize conflicts.

Finally, conflicts spawning from dimensions of value can also be controlled by defining team ground rules and group norms upon project initiation.

Limitations

The fundamental limitation of the methodology related to conflict management is trying to take a complex situation and grouping it into boxes so one can act accordingly. It is important to recognize that real-life situations are not as saturated as depicted by the litterature. Nonetheless, the litterature and methods still provide an excellent starting point for managing conflict as long as the project manager does not fall into the trap of believing to consistently understand the behavior of team members e.g. due to their personality profiles. Likewise, a conflict may not nessecarily follow the conflict stages and the suggested actions for conflict resolution.

Annotated Bibliography

Tonnquist, Bo (2008). Project management. 1st. edition, Bonniers.[3] This book provides insight in project management from the first to last step with each chapter devoted to a phase in the project. The information is particularly insightful in regards to the intangible aspects of project work such as communication, and behavior. Chapter 10 is devoted to daily management of projects such as giving feedback, keeping motivation and dealing with conflicts. In doing so, the Johari window, Maslows hierarchy of needs, conflict style inventories and the ABC method is explained.

Spiess, Wolfgang (2008). Conflict Prevention in Project Management. 1st edition, Springer.[6]. This book is centered on the importance of correctly classifying conflicts and acting accordingly. Particularly, chapter 4, 5 and 8 provide insight to conflict management through the eyes of the PM. Chapter 4 revolves around using psychology to prevent conflicts, and it is also where the 9 conflict stages are introduced. The book contains a number of case studies of proper and improper conflict management.

Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. 5th edition. Project management institute.[8] This books acts as a complete guide to the many facets of project management. It is a good source of information regarding the methodology that can be used when defining scope, scheduling the project, managing risks etc. Chapter 10 is spent on project communications management, which is where conflicts are addressed. The Conflict Style Inventories is introduced along with examples for when the different approaches make sense to apply.

References

- ↑ Definition of ”conflict”, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jones, Gareth. 7th, 2013. Organizational Theory, Design, and Change, chapter 6, 10, 14 (Pearson).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Tonnquist, Bo. 1st, 2008. Project management, chapter 10 (Bonniers)

- ↑ Kahneman, Daniel. 1st, 2011. Thinking fast and slow (Farrar).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ajibolays, Y, 2017. Conflict Management in Projects, [Online], p5. Available at: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org.proxy.findit.dtu.dk/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=8095588&tag=1 [Accessed 8 February 2018].

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Spiess, Wolfgang. 1st, 2008. Conflict Prevention in Project Management, p.48 (Springer).

- ↑ Friedrich Glasl's model of conflict escalation [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Glasl%27s_model_of_conflict_escalation [Accessed 14 February 2018].

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Project Management Institute, 5th, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Project management institute).

- ↑ Myers Briggs personality profiles, [Online] Available at: https://www.16personalities.com/personality-types [Accessed 20 February 2018].

- ↑ Catell's 16 Personality Traits, [Online] Available at: https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/16PF.php [Accessed 20 February 2018].

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Disc Profiles, [Online] Available at: https://www.discanalyse.dk/disc-profil/ [Accessed 20 February 2018].

- ↑ Schneider, Susan. 3rd, 2014. Managing Across Cultures, (Pearson)

- ↑ Lock, Dennis. 9th, 2007. Poject management p. 136 (Gower).