Basic estimation techniques

Abstract

When managing a project, a manager has to achieve specific objects within time, resources and money. This can often be challenging, as there is a lot of uncertainty in doing so. "How can the amount of time for each activity be calculated"? "How many resources are needed to complete every task"? "And how much will the project cost in the end"? This article deals with answering all these questions and focuses on how to come up with educated guesses to these uncertainties.

In the first section, a definition of what an estimation is will be given. A variety of standard tools used in the estimation process will then be presented. Some of these tools and techniques are more complex than others and will therefore require a more detailed explanation. For every presented technique, advantages and disadvantages, as well as examples on how to apply these, will be given in order to give the reader an understanding of how the methods works and what they can be used for.

Lastly, a general guideline on how to approach the estimating process will be provided. Challenges and limitations of using the techniques will also be discussed, as these can variate in accuracy depending on the type of the projects and the project phase in which they are applied. The involved risks when estimating will also briefly be covered here.

Contents |

Definition and Techniques for Estimating

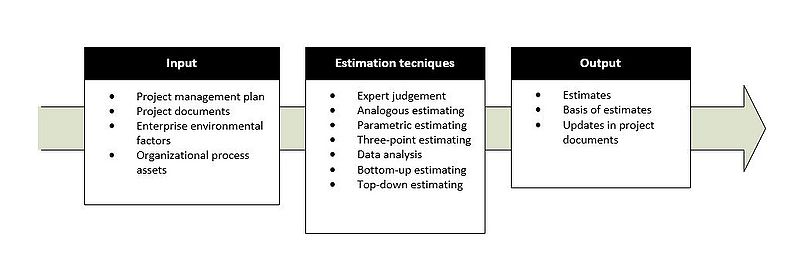

The process of estimating is a common practice within Project Management of predicting a specific value that is not known with a relative accuracy. An estimation can serve different purposes, for example give an indication of the duration for a specific activity, or the amount of resources that must be assigned to a task in order to be completed in time. Figure 1 shows a model for the estimation process.[1]

Estimations are based on different inputs. These can be components from the project management plan as the scope baseline or the schedule plan; project documents as list of activities, assumptions log, resource requirements, register for learned lessons; enterprise environmental factors as market conditions, organizational culture, resource availability; and organizational process assets as policies, scheduling methods and historical data from similar projects. The result of the estimation process, the output, are the calculated estimate and the detailed documentation that supports the approximation. Furthermore, as a result of carrying out the estimation process, some project documents may also be updated.

There exist different estimation techniques. It is important to mention that these are not only limited to the planning phase, but can be used throughout the whole project. This chapter will describe some of the most used techniques in managing projects and give examples of their application. The techniques can be used for estimating costs, efforts, durations, etc.

Expert Judgment

This technique is quite simple and consists in obtaining the judgment of a group or a person with specialized education, knowledge, skill, experience, or training, in the subject that has to be estimated. The expertise can either be provided in the corporation, or externally, for example by turning to a professional consulting agency. An example of carrying this method out, could be having a group of experts to estimate how much the cost for a specific construction material will fluctuate in the next five years. The group will have an open discussion and will eventually at the end agree on what they believe to be the most valid prediction. The problem with doing so, is that there could be a tendency to be persuaded by the majority opinion or the members with the greatest authority on the matter.[2]

A well-known method to overcome these issues, is the Delphi method. According to Helmer (1967), the purpose of this method is to obtain the most reliable consensus of opinion from a panel of selected experts, by questioning them individually around a central subject in a series of rounds, without having the experts confronting each other directly. After every iteration, a host presents the given answers to the group anonymously, thus encouraging the experts to revise their judgement, based on factors other have brought up and that they maybe did not have in consideration during the previuos iteration. At the end of the process the answers are expected to converge towards a more reliable and unbiased estimate for the object of interest.

- Provide documents, data and other kind of information for the experts during the process.

Analogous Estimating

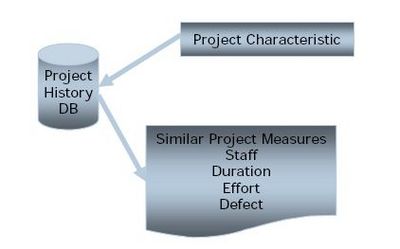

An analogous estimation is based on parameters from projects with broad similarities with the one taken in consideration. This is a particularly useful technique in the early stages of a project, where there is little amount of information available and the board wants for example an estimate of when the project will be completed and how much it will cost in the end. The technique’s main focus is on the overall activities, as it becomes more difficult to give predictions of specific activities, based on information from other projects. The involvement of specific human resources that have been on similar kind of projects is crucial here, as they can give insight on the experiences and challenges they faced, helping thus the project manager in developing valid estimations. Expert judgement will also be helpful when making analogous estimating in order to establish reusability of the information from similar projects.[4]

The method is very simple and generally costs less in terms of time and effort, compared to many other estimation techniques within project management, although it doesn’t work with creative and innovative projects, as these are quite unique.[5]

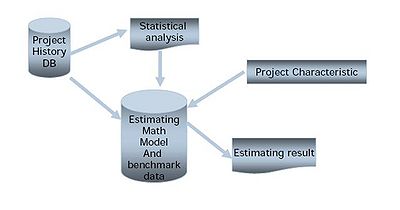

Parametric Estimating

Parametric estimating uses mathematical models that are based on historical data and project characteristics (e.g., duration constraints for a specific activity) to calculate an estimate for specific activity parameters, such as cost, effort, duration, etc. Statistical analyses are usually also performed in order to calibrate the historical data in the mathematical model. Besides, benchmark data from the industry can be utilized to set specific objectives and standards for the model, challenging the project team to improve the work on a type of activity.

Below an application example of this estimation method.

Imagine you have a project where one of your clients wants you to develop a new software within the next two days. The software consists of three parts, respectively A, B and C. Based on internal historical data from similar projects you have worked on before, you can assume that the A section requires 100 hours, the B section 50 hours and the C section requires 30 hours. The A section can be done independently from the other two sections, but B have to be completed before C. You want to estimate how many programmers you need to deliver the software in time. The programmers can work on a section simultaneously and are available 8 hours pr. day each.

The model will consist of the following system of constraints:

Constraint A: 100 / (8*x) ≤ 48

Constraint B+C: (50+30) / (8*y) ≤ 48

where x is the number of programmers working on A, and y the programmers working on B and then C.

The solutions for the system are:

x = 3,84 ≈ 4

y = 4,80 ≈ 5

This means that you will need a total of 9 (4+5) programmers on your team.

Three-point Estimating

bla bla bla

Monte Carlo Simulation

bla bla bla

Bottom-up and Top-down Estimating

bla bla bla

General Guideline

- Prepare to estimate:

- Create estimates:

- Manage estimates:

- Improve estimating process:

Critique on Using Estimates

- One conundrum in estimating, especially for public-sector projects, is that bidders sometimes make overly optimistic estimates in order to win the business.[6] --> just in case

- Estimation should be for normal conditions

- Risks and special situations should be added later

- Optimism Bias

- Is it good to have estimates so early in the process, what happens if something changes?

- Estimates that are there to give an idea, becomes the targets or the constraints.

- Limited in reliability --> sensitivity analysis on accuracy

References

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition)

- ↑ Helmer, O. (1967). Analysis of the future: The Delphi method. The RAND Coroporation, Santa Monica, California.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEstimating_as_an_art - ↑ Green, C. (2006). Estimating as an art—what it takes to make good art. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2006—EMEA, Madrid, Spain. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Kanabar, V. & Warburton, R. D. H. (2011). Leveraging the new practice standard for project estimating. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2011—North America, Dallas, TX. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ https://www.pmi.org/learning/featured-topics/project-estimating