Emotional Intelligence and Leadership

Contents |

Abstract

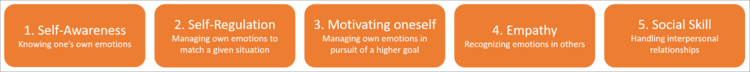

Emotional Intelligence (EI) has received significant attention in both in the scientific and broader community for its potential influence on professional and private success. Several models exist, however the dominant domains of EI in the popular literature are (1) self-awareness, (2) self-regulation, (3) motivation, (4) empathy, and (5) social skills. This article aims at linking features of EI to distinct challenges of leadership, as well as deriving key insights for practitioners in the field of project, program, and portfolio management. Acknowledging that the tasks of a leader are subject to a great variety, three distinct areas are addressed.

Firstly, leaders must choose their own and their team’s priorities among a set of alternatives, which are often generated by large quantities of information coming in at fast speeds. It is discussed that emotions do not degrade decision making per se, as the popular opinion might suggest. Rather, the absence of emotions in decision making can substantially lower the quality of decisions. Further, the influence of positive and negative emotions on decision making is considered, as they can lead to very differing outcomes. Secondly, leaders need to communicate appropriately to their followers. This is especially crucial when giving and receiving feedback. Emotionally intelligent leaders are aware of their followers’ feelings and manage them appropriately when giving feedback. Likewise, leaders are able to accept feedback gracefully through high levels of self-awareness and self-regulation.

Thirdly, leaders are responsible for building effective teams. They can do so by using empathy and further managing their followers’ emotional reactions to unforeseen circumstances. In addition, leaders should be aware of the influence of their own emotional display on their surroundings. Emotions can be subconsciously passed on to one another, through an effect labelled emotional contagion.

Critique regarding the young research area of EI stems from the fact that in an early stage, some inflated claims have been made in the popular literature that could not always be backed up empirically. Further, it is imperative to mention that “leadership” per so does not exist, but rather a variety of different leadership styles. However, there appears to be some relationship between EI and transformational leadership, of which the strength is however not agreed upon. In conclusion, while the importance of emotions in leadership is widely acknowledged, one should be careful about regarding EI as the “magic bullet” for leaders.

About Emotional Intelligence

When talking about intelligence, the first associations that are made typically refer to mathematical or linguistic skills, and “IQ” is a common term that subsequently comes to mind. (However, a large body of literature suggests that there is no such thing as “intelligence” per se, but rather a multitude of them). One such type of intelligence is labelled “emotional intelligence” (hereafter referred to as EI) and has received significant attention for its wide implications on an individual’s private and professional endeavours – even to a degree where it is listed as a requirement in some job descriptions. The basic definition of EI was made by Salovey and Mayer in 1990, describing EI as the “ability to monitor one’s own and others’ emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use the information to guide one’s own thinking and actions”. [1] Salovey et al. further suggested five main domains which characterize emotional intelligence, which were later slightly modified and popularized to a large extent by psychologist Daniel Goleman [2] [3]:

1. Knowing one’s emotions / Self-Awareness. This is also often referred to as self-awareness, meaning the ability to “recognize a feeling as it happens” [2]. A high degree of self-awareness enables one to recognize the effect of own emotions on oneself, as well as others, and act accordingly [3].

2. Managing own emotions / Self-Regulation, so that emotions match a given situation. This builds on the first domain since handling emotions first requires being aware of them.

3. Motivating oneself. This refers to managing emotions (domain 2) in pursuit of a higher goal, such as delaying gratification or resisting certain impulses.

4. Recognizing emotions in others / Empathy. Recognizing emotions in others through empathy also requires emotional awareness in the first place (domain 1). Empathic people have an advantage at understanding the “subtle social signals” which express the needs and wants of others [2].

5. Handling relationships / Social Skills. This task essentially breaks down to the management of emotions in other people. It holds wide implications for any type of interpersonal interactions and is therefore of particular interest when examining emotional intelligence and leadership.

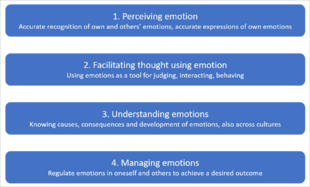

While this first model is known more to the popular audience, it has been criticised for blending personality characteristics with the underlying link of emotions and cognition in EI [4]. An alternative, more distinct model based on individual abilities was put forward by Mayer and Salovey in 1997 [5], which they also updated in 2016 [6]. It encompasses four branches. These in turn include certain types of reasoning, of which some examples are given:

1. Perceiving emotion: This relates to accurately identifying and expressing one’s own emotions, as well as correctly identifying others’ expressions.

2. Facilitating thought using emotion: Using emotions to set the right priorities in thought, make the right judgments and relate to other people.

3. Understanding emotions: Knowing how people feel in the present and might feel in the future given the circumstances, as well as recognizing cultural differences.

4. Managing emotions: Effectively handle one’s own as well as others’ emotions to achieve a certain goal.

Since it is rather likely that practitioners of project, program and portfolio management will come across Goleman’s model of EI, the further discussions in this article are mainly based on this model.

Throughout this article, the term “feelings” is used for both emotions and moods. Emotions are shorter-lasting and triggered by circumstances that are usually easy to identify. Moods on the other hand are feeling states that last longer are not specifically tied to a certain trigger. [7]

Applications of Emotional Intelligence in Leadership

Limitations

Annotated Bibliography

Daniel Goleman, “Emotional Intelligence – Why it can matter more than IQ”, Bantam Books New York 1995

This book can be regarded as a core work on the topic of emotional intelligence and has advanced to an international bestseller. Daniel Goleman argues that emotional intelligence is just as important for a successful private and professional life as the infamous IQ. Goleman further criticises the neglect of schooling emotional intelligence in children and teenagers and provides flagship examples of successful programmes. Throughout the book, interesting and compelling findings from a wide array of psychological studies are discussed and put into the context of the brain´s neurophysiological ways of working.

Jennifer M. George, “Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence”, in Human Relations 53 (8), pp. 1027–1055, 2000

This frequently cited paper examines the role of feelings in a wider array of leadership responsibilities. Many situations which leaders can face are analysed from the viewpoint of emotions and their implications. Since “leadership is an emotion-laden process”, George suggests that emotional intelligence is indeed a part of effective leadership. However, a precise quantitative back-up of some findings lacking in this paper.

Jordan, Peter J.; Ashton-James, Claire E.; Ashkanasy, Neal M. (2014): Evaluating the Claims: Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace. In Kevin R. Murphy (Ed.): A critique of emotional intelligence: What are the problems and how can they be fixed?: Taylor and Francis, 198-210.

The authors critically examine some of the more inflated claims about EI that have mainly been made in the popular press. They do so by evaluating whether empirical results support the claims, as well as checking on the theoretical links to the construct of EI. The authors also look for alternative explanations for the claims by discussing related studies. In summary, this reading helps to put the popular picture of EI into a scientific perspective and is thereby making a valuable contribution for a reflected discourse on the subject.

References

- ↑ Salovey, Peter; Mayer, John D. (1990): Emotional Intelligence. In Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9 (3), pp. 185–211.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Goleman, Daniel (1995): Emotional Intelligence. Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Goleman, Daniel (1998): What Makes a Leader? In Harvard Business Review (Reprint R0401H from Jan. 2004).

- ↑ Jordan, Peter J.; Ashton-James, Claire E.; Ashkanasy, Neal M. (2014): Evaluating the Claims: Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace. In Kevin R. Murphy (Ed.): A critique of emotional intelligence: What are the problems and how can they be fixed?: Taylor and Francis, 198-210.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mayer, John D.; Salovey, Peter (1997): What is Emotional Intelligence? In D. J. Sluyter (Ed.): Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. New York: Basic Books, pp. 3–34.

- ↑ Mayer, John D.; Caruso, David R.; Salovey, Peter (2016): The Ability Model of Emotional Intelligence: Principles and Updates. In Emotion Review 8 (4), pp. 1–11.

- ↑ Ekman, Paul (2021): Mood vs. Emotion: Differences & Traits. Paul Ekman Group. Excerpt from "The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions (1994)". Available online at https://www.paulekman.com/blog/mood-vs-emotion-difference-between-mood-emotion/, checked on 13/02/2021.