Emotional Intelligence and Leadership

Felix Vinzenz Wütherich, Spring 2021

Emotional Intelligence (EI) has received significant attention in both the scientific and broader community for its potential influence on professional and private success. Several models exist, however the dominant domains of EI in the popular literature are (1) self-awareness, (2) self-regulation, (3) motivation, (4) empathy, and (5) social skills. This article aims at linking features of EI to distinct challenges in leadership, as well as deriving key insights for practitioners in the field of project, program, and portfolio management. Acknowledging that the tasks of a leader are subject to a great variety, three distinct areas are addressed.

Firstly, leaders must choose their own and their team’s priorities among a set of alternatives, which are often generated by large quantities of information coming in at fast speeds. It is discussed that emotions do not degrade decision making per se, as the popular opinion might suggest. Rather, the absence of emotions in decision making can substantially lower the quality of decisions. Further, the influence of positive and negative emotions on decision making is considered, as they can lead to very differing outcomes.

Secondly, leaders need to communicate appropriately to their followers to empower and mentor them. Giving and receiving feedback is an integral part of this. Emotionally intelligent leaders are aware of their followers’ emotions and manage them appropriately when giving feedback. Likewise, leaders are able to accept feedback gracefully through high levels of self-awareness and self-regulation.

Thirdly, leaders are responsible for building effective teams. They can do so by using empathy and further managing their followers’ emotional reactions to unforeseen circumstances. In addition, leaders should be aware of the influence of their own emotional display on their surroundings. Emotions can be subconsciously passed on to one another (= emotional contagion), and this can be used to create a high-performing atmosphere.

Critique regarding the young research area of EI stems from the fact that in an early stage, some inflated claims have been made in the popular literature that could not always be backed up empirically. Further, it is imperative to mention that “leadership” per so does not exist, but rather a variety of different leadership styles. There appears to be a relationship especially between EI and transformational leadership, of which the strength is however not agreed upon. In conclusion, while the importance of handling emotions in leadership is widely acknowledged, one should be careful about regarding EI as the “magic bullet” for successful leadership.

Contents |

About Emotional Intelligence

"I have often heard about emotional intelligence - but what is it actually?"

When talking about intelligence, the first associations that are made typically refer to mathematical or linguistic skills, and “IQ” is a common term that subsequently comes to mind. However, a large body of literature suggests that there is no such thing as “intelligence” per se, but rather a multitude of types. One such type of intelligence is labelled “emotional intelligence” (hereafter referred to as EI) and has received significant attention for its wide implications on an individual’s private and professional endeavours – even to a degree where it is listed as a requirement in some job descriptions. The basic definition of EI was made by Salovey and Mayer in 1990, describing EI as the “ability to monitor one’s own and others’ emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use the information to guide one’s own thinking and actions” [1] (p. 189).

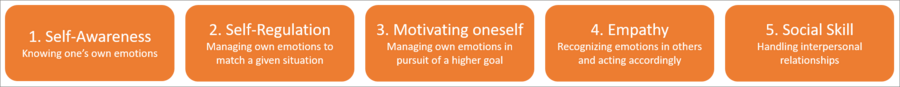

In 1995, the concept of EI was popularized to a large extent by psychologist Daniel Goleman in his best-selling book "Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ". A 1998 article ("What Makes A Leader?") by Goleman in the Harvard Business Review (HBR) further examined EI in the context of business. Goleman's model of EI, as presented in his 1995 book [2] (pp. 46-47) and 1998 HBR article [3] encompasses five domains:

1. Knowing one’s emotions / Self-Awareness. This refers to the ability to “recognize a feeling as it happens” [2]. A high degree of self-awareness is an enabler to recognize the effect of own emotions on oneself, as well as others, and act accordingly.

2. Managing own emotions / Self-Regulation, so that emotions match a given situation. This builds on the first domain since handling emotions first requires being aware of them.

3. Motivating oneself. This refers to managing own emotions (domain 2) in pursuit of a higher goal, such as delaying gratification or resisting certain impulses.

4. Recognizing emotions in others / Empathy. Recognizing emotions in others through empathy also requires emotional awareness in the first place (domain 1). Empathic people have an advantage at understanding the “subtle social signals” which express the needs and wants of others [2].

5. Handling relationships / Social Skills. This task essentially breaks down to the management of emotions in other people. It holds wide implications for any type of interpersonal interactions and is therefore of particular interest when examining emotional intelligence and leadership.

While this first model is known more to the popular audience, it has been criticised for blending the underlying link of emotions and cognition in EI with personality characteristics [4]. However, since it is rather likely that practitioners of project, program and portfolio management will come across Goleman’s model of EI, the further discussions in this article are mainly based on this model.

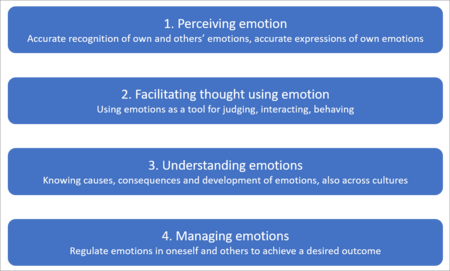

An alternative, more distinct model based on individual abilities was put forward by Mayer and Salovey in 1997 [6], which they also updated in 2016 [5]. It appears to have a higher standing in the scientific literature on EI, and to draw as complete a picture as possible, this "ability model" is also introduced in the following. The model encompasses four branches:

1. Perceiving emotion: This relates to accurately identifying and expressing one’s own emotions, as well as correctly identifying others’ expressions.

2. Facilitating thought using emotion: Using emotions to set the right priorities in thought, make the right judgments and relate to other people.

3. Understanding emotions: Knowing how people feel in the present and might feel in the future given the circumstances, as well as recognizing cultural differences.

4. Managing emotions: Effectively handle one’s own as well as others’ emotions to achieve a certain goal.

Throughout this article, the term “feelings” is used for both emotions and moods. Emotions are shorter-lasting and triggered by circumstances that are usually easy to identify. Moods on the other hand are feeling states that last longer and are not specifically tied to a certain trigger. [7]

Applied Emotional Intelligence for Leaders in Project, Program and Portfolio Management

"Why should I as a leader care about EI - and how can I apply it?"

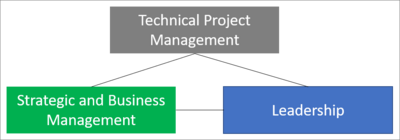

Even though project, program and portfolio management differ in scope and associated tasks [8] (pp. 11–13), a common quality that people who are put in charge within these fields should have is leadership skills [9] (p. 56), [10] (p. 18), [8] (p. 15). To put the importance of leadership into a broader perspective, the Project Management Institute (PMI) provides a useful visualization through the PMI Talent Triangle ® [11] (p. 52).

Leadership is thereby an integral quality for practitioners in project, program and portfolio management next to distinct management skills - and EI has been mentioned as part of the leadership side of the Talent Triangle ® [12].

At the core, leadership is about influencing people so that they voluntarily work towards some shared goals [13]. Consequently, leadership is also a process full of emotions for both leaders and followers [14]. The topic of leadership is wide, and a multitude of leadership theories exists in the literature. It is not within the scope of this article to go into detail about these, but rather to explore the benefits of applied EI in common leadership tasks in project, program and portfolio management.

Goleman argues that EI be be learned to some degree through training [3] - so the reader is encouraged to stick with this article regardless the individual background. The tasks that are considered in this article are:

- Setting the right priorities, relating to effective decision making

- Communication: Motivating and mentoring team members, relating to giving and receiving feedback

- Building effective teams, relating to creating a work environment that promotes high performance

Setting the Right Priorities

Effective leaders need to concentrate "on the important things", and must therefore permanently prioritize their own, as well as their team's working activities [9] (p. 62). This task ultimately comes down to making good decisions when faced with a (large) set of alternatives.

Importance of Feelings in Decision Making

“Don’t let your emotions guide you” is a phrase that decision makers hear often. It is acknowledged (and likely a part of the reader’s own experience) that moods and emotions indeed have an influence on the quality of decision making [14]. However, it is worth pointing out that the opposite can equally hold true: The absence of emotions can also have negative consequences for decision making.

This has been observed in patients who had undergone brain surgery, and whose brain areas for generating emotions and moods were damaged or removed during the procedure. Even though the IQ-level of these patients, as well as their cognitive abilities were by no means impaired, the quality of their decisions suffered drastically. As illustrated in detail by Goleman [2] (p. 58), based on findings from neurologist Antonio Damasio [15] (pp. 34-51), one such patient was indeed able to rationally reason for and against each alternative he was faced with. However, the lack of any feelings about each option left the patient unable to choose, since it was not possible to assign any “value” to the alternatives. Instead, all options simply appeared neutral.

Ultimately, the patient could not be trusted to “perform an appropriate action when it was expected” [15] (p. 37).

Possible Drawbacks of Feelings in Decision Making

Having acknowledged the importance of feelings on decision making, it is imperative to consider the drawbacks they can have in this regard. Positive moods can enable an individual to think more broadly and complex. However, they also induce a bias: When in a state of positive moods, the brain tends to weight incoming information more positively [2] (pp. 96–97).

As a result, strong positive feelings can lead a decision maker to rely less on careful and logical thought. This facilitates making riskier decisions without rationally thinking them through. As the psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman puts it, “a happy mood loosens the control of System 2 over performance” [16] (p. 69). System 2, according to Kahneman, refers to the rational and conscious way of thinking, as opposed to System 1, which stands for the subconscious and emotion-driven type of thinking [16] (p. 29).

Negative emotions on the other hand can favour (overly) careful decisions. This can be explained from a biological viewpoint: A bad mood may be a signal of a hidden danger, which encourages more careful thinking – in contrast to a good mood which indicates that it is safe to be less vigilant. [16] (p. 69)

However, extreme negative emotions tend to have a disastrous effect on rational decision making. High anxiety for instance can essentially paralyze an individual’s rational thoughts [2] (p. 94) – any reader who has ever blacked out during an exam can likely relate. In similar fashion, high levels of anger also undermine rational reasoning [2] (p. 65).

Synthesis and Recommendations for Leaders

It has been found that people with a capability to identify their current emotions as well as distinguish among them can make better decisions than those who do not possess this trait, which can be explained by an “enhanced ability to control the possible biases induced by those feelings” [17].

Leaders should therefore be aware of their current feelings when making decisions – this relates to “self-awareness” and “self-regulation” in Goleman’s model of EI. In this regard, the famous phrase “sleep on it” may actually be good advice for leaders who are about to make a decision when feeling strong positive emotions. Likewise, it is advised to postpone decisions when feeling very angry or stressed.

There are situations in which feelings are particularly likely to influence decisions [14], which especially leaders should be aware of. A common issue when prioritizing in project, program or portfolio management is an abundance of incoming, possibly ambiguous information in a short amount of time – and the need to make a good decision fast. Mastering this complex challenge not only requires cognitive and analytical abilities. It is equally important to be aware of how such a task affects feelings, which can then in turn influence decision making. When individuals are involved in this type of situation, they tend to engage in “substantive processing” [18]. Present moods and emotions are particularly likely to influence judgments during substantive processing – in other words, a complex situation generally favours moods and emotions to guide decisions [14]. This effect is also called “affect priming” [18].

Kahneman uses the term “cognitive strain” for a thinking process which requires significant effort. He however illustrates that cognitive strain activates the rational mind contrary to emotion-guided thinking, thereby encouraging analytical and careful thoughts [16] (p. 65). Nonetheless, I argue that a demanding situation can easily turn into an overstrained one – provoking strong negative feelings which degrade decision making.

Communicating Appropriately

Both the quantity, as well as the quality of communication is an integral part of successful leadership. Leaders need to communicate sufficiently, and it has been shown that the most successful project managers indeed devote around 90% of their time to communication [9] (p.61). The focus in this section lies however on the quality of communication.

An important leadership skill for project, program and portfolio managers is to coach and motivate their followers [11] (pp. 21, 26, 30). In this regard, one communication task that leaders should be firm with is giving and accepting feedback [9] (p.61). “Without feedback people are in the dark” [2] (p. 172) – feedback is vital for letting employees and leaders know where they stand and what they can improve on. Ultimately, the effectiveness of whole organizations depends on how each distinct part may change each other for the better (or worse!) through feedback. (ibid.)

Recommendations for Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is to a large extent about managing emotions in others. It is therefore advised to be fully aware of the feelings that one's own statements can potentially trigger. This relates especially to the “Understanding emotions”-branch in the EI ability model, which emphasizes the importance of knowing causes, consequences and the development of emotions over time [5]. Goleman [2] (p. 173) describes that the way criticism is delivered in the workplace can leave an employee empowered and optimistic, or completely demotivated. When feeling attacked, individuals tend to become defensive and in the worst case, they “stonewall”. This means they cut all contact with the overly harsh manager, and this can essentially kill a team’s performance.

Recommendations for Receiving Feedback

Receiving feedback on the other hand relates especially to self-awareness and self-regulation [3]. Recognizing and understanding one’s own feelings is an important ingredient in accepting criticism. A leader who is aware of the unease he feels when a concern about his performance is raised can separate this feeling from the facts and learn from the received feedback. Moreover, self-aware individuals know their strengths and weaknesses and are not afraid to be open about them [3]. I argue that this encourages followers to provide more feedback, which in turn gives the leader the opportunity to learn even more about him- or herself. Ultimately, an open and approachable leader helps to build a sense of trust within an organization.

Shaping a High-Performance Atmosphere

Project, program and portfolio managers should promote a high-performance atmosphere in their respective teams [11] (pp. 21, 26, 30). In more detail, a leader needs to install excitement and enthusiasm as well a sense of collaboration and trust, among other traits [14]. This requires emotional intelligence, as leaders not only have to correctly recognize their followers’ emotions using empathy, but also manage their emotions proactively.

Distinguishing between Expressed and True Emotions

In today’s dynamic world, changing circumstances and unexpected events are part of day-to-day business. While leaders certainly have to anticipate these changes and act as a buffer, they should equally be able to foresee and manage their followers’ emotional reaction to them [14]. This way, a level of overall excitement in the team can be maintained. For this, it is imperative that leaders possess the ability to distinguish between the emotions their followers are actually experiencing, as opposed to the emotions they are displaying [14]. For instance, an employee might put on a fake smile after a change to his tasks has been announced, while feeling disappointed or angry at the same time. Empathic leaders are attuned to the subtle signals in facial expression, body language or tone of voice. As a result, it would be the leader’s emotional intelligence (not technical expertise) signalling to the leader that something is wrong. Subsequently, the reason for the employee’s true feelings can be investigated, and appropriate measures be taken.

It is important to consider that effectively tuning in becomes even more challenging in cross-cultural teams, as different social norms may apply for which feelings are shown under which circumstances [2] (p. 129). These norms are also labelled “display rules” [19].

Using Emotional Contagion

When aiming to create a work environment in which people feel at ease and collaborate, “emotional contagion” is a term that leaders should be familiar with. People tend to unconsciously mimic facial and vocal expressions as well as body language of others [20] (p. 26). Goleman illustrates that people “catch feelings from one another as if they were some kind of social virus” [2] (p. 131). This transfer of feelings is mostly very subtle. Using electronic sensors, it has been measured that people’s facial muscles react to seeing smiling or angry faces in a way that the emotion is mimicked [2] (p. 132). When mimicking other people's expressions of feelings, a small amount of the other person's emotions can be felt (described as feedback) [20] (p. 26). Goleman [2] (p. 133) describes that this subtle exchange of emotions can also affect how well an interaction is going. There is an “orchestration” with which nonverbal expressions are exchanged. This can be as simple as nodding at the right time or leaning in when the other person leans back. Thereby, a feeling of closeness can be created which is entirely unconscious – an important step in installing a sense of collaboration and trust.

It has even been shown that moods and emotions can transfer from a person who is highly expressive with their feelings to person who is more passive [2] (p. 132). A leader who can effectively display a high degree of excitement and enthusiasm can for instance install the same feeling in his or her followers [21].

Concluding, to shape a high-performance atmosphere, emotionally intelligent leaders can foresee their followers’ emotional reactions and (re-)act accordingly. Further, they are aware and can make use of the potential of their own emotional display on their followers' feelings.

Limitations

"What should I as a leader be aware of when I hear the buzzword "emotional intelligence"?"

Firstly, leaders in project, program, or portfolio management need to be cautious about inflated claims. The research area of EI itself is rather young, yet it has gained large popularity in a short amount of time. The importance of some notions of EI, such as emotional awareness or self-control had been known for decades [22]. However, the core concept of EI was not proposed until 1990 by Salovey et al. (Goleman 1995, p. 361), while only five years later, Goleman made the field known to a worldwide audience in his international bestseller on EI. This is a speed with which empirical studies and scientific reviews have not always been able to keep up, and a point of critique is that some early claims have been exaggerated beyond truth to be attractive to the broad audience. For instance, a claim about leadership that “outstanding leaders’ emotional competencies make up to 85% to 100% of the competencies crucial for success” [23] (p. 187) has been criticized for being unprecise and potentially misleading [4].

Secondly, a difficulty that arises when talking about emotions and leadership is that there is no such thing as “leadership” per se, but rather a multitude of different leadership styles [9] (p. 65). One style of leadership which has been associated with EI particularly often is transformational leadership. It is the job of a transformational leaders to “inspire, energize, and intellectually stimulate their employees”, according to one of the field’s key researchers Bass [24]. Further, transformational leaders encourage their followers to be creative and build individual rapport with them [9] (p. 65). There is empirical evidence of a positive correlation between EI and transformational leadership, however, the strength of these ties is still debated [25].

In this regard, the difference between leadership and management [9] (p. 64) is also worth emphasizing. Being a leader in project, program and portfolio management is not all about inspiring and energizing – sometimes for instance, mere positional power (ibid.) has to be used to direct followers, disregarding the feelings they might have about it. Still, I argue that EI could help a leader in bringing the team together after such tense times. In this sense, the PMI Standard on Project Management is right to say that “the right balance for each situation” needs to be found [9] (p. 64). It is therefore advised to not regard EI as a cure-all [4], but rather a window of opportunity for the outlined leadership tasks in this article – bearing in mind that influencing people to work towards a shared goal never goes without emotions. The potential applications of EI in leadership are therefore very wide, and the reader is encouraged to refer to the annotated bibliography for further reading.

Annotated Bibliography

Goleman, Daniel (1995), “Emotional Intelligence – Why it can matter more than IQ”, Bantam Books, New York

This book can be regarded as a core work on the topic of emotional intelligence and has advanced to an international bestseller. Daniel Goleman argues that emotional intelligence is just as important for a successful private and professional life as the infamous IQ. Goleman further criticises the neglect of schooling emotional intelligence in children and teenagers, and provides flagship examples of successful programmes. Throughout the book, interesting and compelling findings from a wide array of psychological studies are discussed and put into the context of the brain´s neurophysiological ways of working.

Goleman, Daniel (1998): What Makes a Leader? In Harvard Business Review (Reprint R0401H from Jan. 2004).

This article is a much-noticed outline of the potential of EI on leadership in a business context. Goleman provides many concrete cases in which concepts of EI are beneficial for leaders. He also explains how certain elements of EI such as empathy can be learned through training.

Mayer, John D.; Caruso, David R.; Salovey, Peter (2016): The Ability Model of Emotional Intelligence: Principles and Updates. In Emotion Review 8 (4), pp. 1–11.

A guide to the more "scientific" model of EI. The authors critically revise and update their 1997 "ability model", giving detailed information about the types of reasoning that each branch of emotional intelligence encompasses. Their model description appears to be more distinct than Goleman's popular model of EI. The authors further examine the position of EI among other intelligences, such as personal and social intelligence.

George, Jennifer M. (2000), “Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence”, in Human Relations 53 (8), pp. 1027–1055

This frequently cited paper examines the role of feelings in a wider array of leadership responsibilities. Many situations which leaders can face are analysed from the viewpoint of emotions and their implications, backed up by an extensive research in the literature. Since “leadership is an emotion-laden process”, George suggests that emotional intelligence is indeed a part of effective leadership. However, a precise quantitative back-up of some findings is lacking in this paper.

Jordan, Peter J.; Ashton-James, Claire E.; Ashkanasy, Neal M. (2014): Evaluating the Claims: Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace. In Kevin R. Murphy (Ed.): A critique of emotional intelligence: What are the problems and how can they be fixed?: Taylor and Francis, 198-210.

The authors critically examine some of the more inflated claims about EI that have mainly been made in the popular press. They do so by evaluating whether empirical results support the claims, as well as checking on the theoretical links to the construct of EI. The authors also look for alternative explanations for the claims by discussing related studies. In summary, this reading helps to put the popular picture of EI into a scientific perspective and is thereby making a valuable contribution for a reflected discourse on the subject.

Kahneman, Daniel (2011): Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Penguin Books; Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Daniel Kahneman's international bestseller is not focusing on emotional intelligence per se, but the cognitive biases and ways of thinking that shape an individual's decisions and behaviour. The book provides compelling insights from a large body of psychological studies. It is a useful literature especially for leaders, as it shows how rational thought can easily be compromised by other forces at play, which are also not necessarily related to emotions.

Chan, Jonathan T.; Mallett, Clifford J. (2011): The Value of Emotional Intelligence for High Performance Coaching. In International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 6 (3), pp. 315–328.

This paper offers a refreshing view on EI not from the perspective of business, but of high-performance sports coaching. Mayer et al.'s ability model is applied to the role of the coach and the relationship to his team as a whole, as well as individual athletes.

References

- ↑ Salovey, Peter; Mayer, John D. (1990): Emotional Intelligence. In Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9 (3), pp. 185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FDUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Goleman, Daniel (1995): Emotional Intelligence. Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Goleman, Daniel (1998): What Makes a Leader? In Harvard Business Review (Reprint R0401H from Jan. 2004).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Jordan, Peter J.; Ashton-James, Claire E.; Ashkanasy, Neal M. (2014): Evaluating the Claims: Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace. In Kevin R. Murphy (Ed.): A critique of emotional intelligence: What are the problems and how can they be fixed?: Taylor and Francis, 198-210.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mayer, John D.; Caruso, David R.; Salovey, Peter (2016): The Ability Model of Emotional Intelligence: Principles and Updates. In Emotion Review 8 (4), pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1754073916639667

- ↑ Mayer, John D.; Salovey, Peter (1997): What is Emotional Intelligence? In D. J. Sluyter (Ed.): Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. New York: Basic Books, pp. 3–34.

- ↑ Ekman, Paul (2021): Mood vs. Emotion: Differences & Traits. Paul Ekman Group. Excerpt from "The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions (1994)". Available online at https://www.paulekman.com/blog/mood-vs-emotion-difference-between-mood-emotion/, checked on 13/02/2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Project Management Institute (PMI) (2017): The Standard for Portfolio Management - Fourth Edition.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Project Management Institute (PMI) (2017): Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) - 6th Edition.

- ↑ Project Management Institute (PMI) (2017): The Standard for Program Management - Fourth Edition.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Project Management Institute (PMI) (2017): Project Manager Competency Development Framework - Third edition.

- ↑ Project Management Institute (PMI): The PMI Talent Triangle. Your Angle on Success. Available online at https://www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/documents/public/pdf/certifications/talent-triangle-flyer.pdf, checked on 16/02/2021.

- ↑ Hitt, William D. (1993): The Model Leader: A Fully Functioning Person. In Leadership & Organization Development Journal 14 (7), pp. 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437739310046976

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 George, Jennifer M. (2000): Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. In Human Relations 53 (8), pp. 1027–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700538001

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Damasio, Antonio (1994): Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Kahneman, Daniel (2011): Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Penguin Books; Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Seo, Myeong-Gu; Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2007): Being Emotional during Decision Making - Good or Bad? An Empirical Investigation. In Academy of Management Journal 50 (4), pp. 923–940. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.112.2224

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Forgas, Joseph Paul (1992): Affect in Social Judgments and Decisions: A Multiprocess Model. In Advances in Experimental Psychology 25, pp. 227–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60285-3

- ↑ Ekman, Paul (2018): Are facial expressions universal or culturally specific? A look at cultural expressions in public and private. Paul Ekman Group. Excerpts taken from Dr. Paul Ekman’s scientific autobiography, Nonverbal Messages: Cracking the Code (pp. 70-74). Available online at https://www.paulekman.com/blog/facial-expressions-universal-culturally-specific/, checked on 17/02/2021.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hatfield, Elaine; Rapson, Richard L.; Yen-Chi, Le L. (2009): Emotional Contagion and Empathy. In Jean Decety, William Ickes (Eds.): The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Social neuroscience).

- ↑ Chan, Jonathan T.; Mallett, Clifford J. (2011): The Value of Emotional Intelligence for High Performance Coaching. In International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 6 (3), pp. 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.3.315

- ↑ Fambrough, Mary J.; Hart, Rama Kaye (2008): Emotions in Leadership Development: A Critique of Emotional Intelligence. In Advances in Developing Human Resources 10 (5), pp. 740–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422308323542

- ↑ Goleman, Daniel (1998b): Working with Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

- ↑ Bass, Bernhard M. (1990): From Transactional to Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the Vision. In Organizational Dynamics 18 (3), pp. 19–31. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.895.1330

- ↑ Kim, Hyejin; Kim, Taesung (2017): Emotional Intelligence and Transformational Leadership: A Review of Empirical Studies. In Human Resource Development Review 16 (4), pp. 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484317729262