Blake-Mouton Managerial Grid

This article is mainly based on; the Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence, written by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton.

Contents

|

Abstract

Project managers play a critical role of leading a team towards achieving the objectives of a project. The leadership style of a project manager may be a result of combination of multiple factors related to the project or be of a personal preference. Leadership is a productive field of study, with many theories reaching back decades. Thoughts on leadership and the ideal characteristics of a leader have evolved through time, but some of the thoughts have passed the test of time.

The Managerial Grid developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton was first published in 1964. It was the outcome of their research for Exxon, where they worked towards improved leader effectiveness. It was developed with influence from Fleishman's work, using attitudinal dimensions rather than behavioural, like Fleishman.

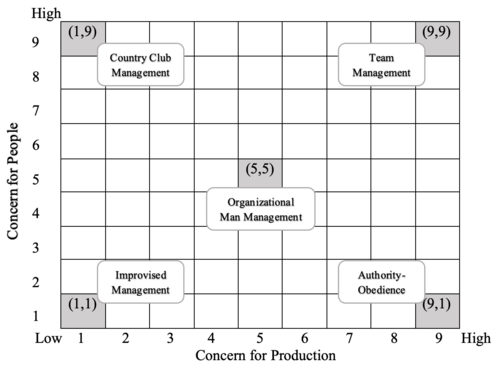

The Managerial Grid is a 9x9 matrix and it quantifies the degree to which the emphasis is on tasks and the emphasis is on the relationship with the subordinates, with Concern for Production as the x-axis of the matrix and Concern for People as the y-axis. Blake and Mouton labelled and characterised the extreme corners as well as the center of the matrix. The Managerial Grid is a widely accepted as an important and critical analysis of the behaviour of a leader. Its simplicity captures vital truths about management styles and implications. The following consists of what is needed to know about the Managerial Grid, how to apply it, suggestions of improvements for a leader, as well as addressing main limitations of the Grid and finally, some literature suggestions for further studies on the Grid.

Leadership in Project Management

Project manager plays a critical role of leading a team to achieve the objectives of a project. He provides the team with leadership, planning and coordination through communication. Leadership skills are the ability to guide, motivate and direct a team [1] (p.56). These skills may include abilities regarding negotiation, resilience, communication, problem solving, decision making, critical thinking and interpersonal skills. A common denominator in all projects is people, and therefore, a big part of the role of a project manager involves dealing with people and different stakeholders of a project. The project manager should strive to be a good leader, as leadership is a crucial part of a successful project [1] (p.60).

Project managers need to possess over both leadership abilities as well as abilities in management, in order to succeed at their job. The key is finding the correct balance for all occurring situations. It is often displayed in the project manager’s leadership style, how the management and leadership is employed. The leadership style of a project manager may be result of a combination of multiple factors related to the project or be more of a personal preference. The style can change and evolve through time, based on the factors in play each time. The major factors are for example characteristics of different elements related to the project, that is characteristics of the leader, of the team members, of the organisation and/or of the environment [1] (p.65). Thoughts on leadership and the ideal characteristics of a leader have evolved through time, but some have passed the test of time, one of them being the Managerial Grid.

Development of the Managerial Grid

The Managerial Grid was developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton between 1958 and 1960 and it was first published in 1964. Blake and Mouton were management theoreticians, and the model was the outcome of their research for Exxon, where they worked towards improving leader effectiveness [2]. The Grid was developed with influence from Fleishman’s work and according to him, there were two underlying dimensions of leaderships’ behaviour which he called consideration and initiating structure.

Blake and Mouton used attitudinal dimensions rather than the behavioural like Fleishman, their attitudinal dimensions being Concern for Production and Concern for People. The dimensions are claimed to reflect the character of thinking and feeling applied behaviourally to achieve an intended purpose, rather than being a reflection of behaviour [3] (p.6).

The Managerial Grid

The Managerial Grid is a 9x9 matrix with Concern for Production, that is getting results, as one dimension of the grid or as the x-axis. The other dimension, or y-axis, being Concern for People, that is subordinates and colleagues. The phrasing of concern for is not referring a mechanical term that indicates the amount of actual production achieved or actual behaviour towards other people. It is more about indicating the character and strength of assumptions present behind any given style of leadership [4]. The dimensions are viewed as interdependent and the interaction of the two dimensions to create a specific leadership approach, is specified by a comma [3] (p.4). The Managerial Grid is a widely accepted as an important and critical analysis of the behaviour of a leader. Its simplicity captures vital truths about management styles and implications [5].

Concern for Production

Concern for production includes results, bottom line, performance, profits or mission. It covers both quantity and quality and can be displayed in different forms. It may be revealed in the scope of a decision, the number of ideas or products that the development converts into sellable products, accounts processed in a collection period, or the service quality by staff. It also may take the form of measurements of efficiency, amount produced, amount of time needed to complete production, sales volume or attainment of specified level of quality. Production can be a project or whatever an organisation requires their employees to accomplish [4] (p.10).

Concern for People

An important factor regarding determination of effectiveness are the assumptions that managers make about people, as they lead with and through other people. Concern for people can be revealed in different ways. Some show it in their efforts to ensure that their subordinates like them, while others are more concerned that subordinates finish their jobs. Despite the differences, getting results based on respect and trust, sympathy, obedience, or understanding and support, is a manifestation of Concern for people. It can become evident through salaries, benefits, job security, etc. [4] (p.10).

Intercorrelation of Concerns

The Managerial Grid is shown as a nine-point scale, where 1 is low concern, 5 is an average amount of concern and 9 is high concern, numbers in between denote intermediate degrees of concern. The way these concerns are expressed by a leader, defines the usage of authority. If the concern for people is high, coupled with low concern for production, the leader weighs the well-being and happiness of the people the most. The other way around, if the concern for production is high but the concern for people is low, the leader is production efficiency oriented [4] (p.11).

To increase managerial competences and productivity in people, a leader needs to know different leadership styles. Blake and Mouton identified five benchmark styles, that display significant differences in characteristic actions and outcomes. Following are the titles they used, but the styles have often gotten different titles. Figure 1 shows the Grid with the five styles.

Leadership Styles

1,1 – Improvised Management

1,1 or Improvised Management is located in the left corner, representing a minimum concern for both production and people. 1,1 oriented manager seeks to continue the current activities to remain a member of the organisation, by applying minimum effort. He avoids activities that reveal that he is uninterested, as he knows that can get him fired. The involvement of subordinates is likely low, as a result from the lack of leadership [6] (p.31).

9,1 – Authority-Obedience

9,1 or Authority-Obedience is located in the lower right corner, where the 9 in concern for production intersects with 1 of concern for people. It displays a maximum concern for production combined with minimum concern for people. A 9,1 oriented manager concentrates on maximising production by exercising power and authority and achieving control over subordinates. He fears failure and is unaccepting of his own weaknesses and inadequacy. He is likely to be involved and committed to organisational purposes and views subordinates as little more than agents of production and they are seen as only being employed to do the dictates of the manager [6](p.28).

5,5 – Organization Man Management

5,5 or Organization Man Management is located at the center of the grid. It is about fulfilling organisational performance through a balance of completing necessary jobs, while maintaining morale of people at a satisfactory level. A 5,5 oriented manager is anxious about potential criticism and is afraid of not belonging. He tries to gain acceptable results in doing what has to be done, but at same time avoiding action that might lead to potential criticism [6](p.32).

1,9 – Country Club Management

1,9 or Country Club Management is located at the top left corner, where minimum concern for production is combined with a maximum concern for people. The manager fears most to suffer rejection and feeling unworthy of acceptance. His efforts are focused towards making the subordinates feel important and satisfied with the working conditions, as an attempt to avoid being rejected by them. The key focus is on human dimension, with production accomplishment almost eliminated, that is good morale at the expense of achieving organisational results [6](p.30).

9,9 – Team Management

9,9 or Team Management represents the top right corner, a maximum concern for both production and people. The 9,9 oriented manager is able to contribute to the situation where he performs as well as enabling other to contribute. It is a goal-cantered, team approach seeking maximum results through participation, commitment, involvement, decisions and conflict solving of all team members. A consequence of 9,9 management style is that subordinates develop commitment to contribute to organisational achievements. 9,9 leadership style is put up as the soundest approach to managing and leading production with and through people. It leads to a combination of high actual productivity, good creativity and increased job satisfaction by all subordinates [6](p.17).

Additional Leadership Styles

Blake and Mouton identified three additional managerial orientations, each of which a combination of the basic theories already identified. The first one is Paternalism, a combination of 9,1 direction and control, and 1,9 rewards through praising compliance. At each extreme, this managerial style is prescriptive about what the team needs and how they supply it. The team management of adapting to the teams’ needs, is not present [4] (p.140).

The second is Opportunism, which is when all five styles are relied on in an unprincipled way, for personal advancement. It is a highly opportunistic manager, prepared to exploit any situation and manipulate their people into doing so [5].

Finally, is Facade, with no specific combination of styles. Facade is referring to a front or a cover, for the real approach lying behind it. The general feature of all facades is that the manager avoids revealing the content if his mind but giving the impression of doing so [4] (p.155).

Application of the Grid

The Managerial Grid helps to examine assumptions about leadership and characterise leadership styles [3] (p.7). We can analyse our assumptions once we become aware of the character and depth of them, identifying the good and bad consequences of our actions. Alternative assumption can provide a sounder basis for our actions, so we can try to practice applying them until they become a characteristic of our leadership style [4](p.6). The Grid becomes a good management tool, when used properly. It can help a leader to reflect on their leadership style and the effects it has on their team’s motivation and productivity. It can be used to increase effectiveness of an organisation on an in-company basis. Once studied, it can be used to improve selection, training, development and coaching within an organisation. It can help to improve participation, involvement and commitment, to solve conflicts, setting goals, and so on [4](p.17).

How to use the Grid

According to Blake and Mouton, leadership can be described by identifying main elements, each of which is a leadership factor that can be isolated and examined. The identified elements are six and are vital to effective leadership as none can compensate for the lack or overabundance of other. The elements are initiative, inquiry, advocacy, conflict resolution, decision making and critique [4](p.18).

Step 1 - Identify Leadership style

The first step of using the Managerial Grid, is to measure individual’s leadership style against these dimensions which can be done through the following questionnaire [3](p.9) . Selecting one statement for each element, by for example drawing a circle over them and afterwards seeing which letter came up most frequently. It is essential to strip away as much self-deception as possible, to see the real underlying assumptions. To do so, one needs to take time, reflect and assess which statements of each element reflects their actual leadership style the most [7].

The following questionnaire is based on pages 2-5 in the Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence [4].

| Questionnaire | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiative | |||||||

| A | I put out enough to get by. | ||||||

| B | I initiate action the help and support others. | ||||||

| C | I seek to maintain a steady pace. | ||||||

| D | I drive myself and others. | ||||||

| E | I stress loyalty and extend appreciation to those who support me. | ||||||

| F | I exert much effort and on others to join in enthusiastically. | ||||||

| Inquiry | |||||||

| A | I go along with facts, beliefs, and positions given to me. | ||||||

| B | I look for facts, beliefs and positions that suggest all is well. I don’t like challenging others. | ||||||

| C | I take things at face value but check facts, beliefs and positions, if critical. | ||||||

| D | I investigate facts, beliefs and positions, to control and so nobody makes mistakes. | ||||||

| E | I double-check what others say and verify their positions before complimenting. | ||||||

| F | I search for information and validate it. I am inviting and listen for others’ opinions and acknowledge them. | ||||||

| Advocacy | |||||||

| A | I respond if asked, but avoid taking sides by not revealing my opinions, attitudes or ideas. | ||||||

| B | Even having some reservations, I embrace opinions, attitudes and ideas of others. | ||||||

| C | I try to meet others halfway and express my opinions, attitudes and ideas. | ||||||

| D | I stand up for my opinions, attitudes and ideas, even if it means rejecting others. | ||||||

| E | I hold strong convictions but let others express ideas and help them to think objectively. | ||||||

| F | I tell my convictions and concerns but if others’ idea is sounder, I acknowledge it. | ||||||

| Conflict Resolution | |||||||

| A | I seek to stay out of conflict by remaining neutral. | ||||||

| B | I avoid conflicts but if they appear, I keep people together by soothing feelings. | ||||||

| C | I try to find a reasonable position that others find suitable, when a conflict arises. | ||||||

| D | I try to cut off a conflict when it arises or try to win my position. | ||||||

| E | I terminate conflicts when they arise but thank people for expressing their mind. | ||||||

| F | I seek out reasons for conflicts, to resolve possible underlying causes of it. | ||||||

| Decision Making | |||||||

| A | I let others make decisions. | ||||||

| B | I make decisions that maintain relations and encourage others to make decisions. | ||||||

| C | I search for decisions that others accept. | ||||||

| D | I am seldom influenced by others and I make my own decisions. | ||||||

| E | I make an effort so that my decisions are accepted, and I must have the final say. | ||||||

| F | I seek understanding and agreement of others, as I feel it is important to arrive at a sound decision. | ||||||

| Critique | |||||||

| A | I avoid giving feedback. | ||||||

| B | I avoid giving negative feedback but give encouragement given an opportunity. | ||||||

| C | I give indirect feedback as a suggestion for improvement. | ||||||

| D | I pinpoint weakness to measure up. | ||||||

| E | I give others feedback and consider that it is for their best interest to accept it. | ||||||

| F | I encourage a two-way feedback in order to strengthen performance. | ||||||

The following table, based on page 13 in the Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence, shows which statement corresponds to each style.

This provides an opportunity to consider if you should wish to improve your managerial leadership behaviour.

| Statement | Style |

|---|---|

| A | 1,1 |

| B | 1,9 |

| C | 5,5 |

| D | 9,1 |

| E | Paternalism |

| F | 9,9 |

Step 2 - Suggestions for Improvement

Following are suggestions by Blake and Mouton, for gained leadership skills striving towards Team Management.

Improvements for 9,1:

- Motivation: Increase subordinates’ involvement by letting them participate and open up.

- Initiative: Where you have been taking the shorts, invite others to do it. Help them act, instead of always acting yourself.

- Inquiry: Consult with subordinates that may have information for achieving better result. Do not discount information coming from someone, even if you dislike them.

- Advocacy: Help others to say what they think and listen, before stating your own. Don’t demand others to accept your statements as final.

- Conflict: Listen to others and don’t reject differences, get them in the open.

- Decisions: Slowdown and consult with others. Take reservations into account and communicate the rationale behind your decisions, rather than stating the conclusion.

- Critique: Realize that critique does not have to be blame-including or fault-finding. Feedback should be a two-way street [4] (p.33).

Improvements for 1,9:

- Motivation: If you are polite and solicitous when it obscures real issues, it might make others feel uneasy.

- Initiative: Take initiative when you ordinarily tend not to.

- Inquiry: Increase preparation for meeting as it makes you feel self-assured. Ask questions that invite explanations.

- Advocacy: Rehearse your convictions so they are clearly understood and be specific.

- Conflict: Conflicts are inevitable, but differences can be examined without increased tension. Smoothing over difference is not a solution.

- Decisions: Do not postpone unpleasant decisions.

- Critique: Realize that others want to help, feedback is good and should be a two-way street [4] (p.48-49).

Improvements for 1,1:

- Motivation: Reassess your degree of involvement and think about the consequences of being fired, it may be enough to reactivate your leadership.

- Initiative: Your subordinates are likely aware of your uninvolvement, but they are also likely to encourage you once seeing your increased interest.

- Inquiry: Read more to use as a background for further inquiry with subordinates.

- Advocacy: Answer questions straightforwardly and make your standpoint clear, if needed give the questioner your pledge to further investigation, within a timeframe.

- Conflict: When people disagree, explore and resolve your differences instead of walking out. Others are usually willing to find a mutual basis of agreement.

- Decisions: Involving several subordinates in solving complex problems, will strengthen the practice of a sound teamwork.

- Critique: Ask subordinates for a feedback, working as a team increases productivity [4] (p.62-64).

Improvements for 5,5:

- Motivation: Consider whether the reaction you receive from others indicates respect, or if they simply reflect their approval of your conformity-based actions.

- Initiative: Take on an obvious problem rather than waiting for an approval.

- Inquiry: Be thorough to avoid being uninformed, ask questions ensuring full understanding.

- Advocacy: Don’t shape your convictions to make other agree, speak your mind.

- Conflict: Disagreement can lead to valuable innovation, ask for information if necessary and be open.

- Decisions: Only you can make certain decisions, although you can ask others for input. Make reasonable decisions without delay. Teamwork based on majority thinking might be in the right direction.

- Critique: Feedback can reduce needless mistakes. Critique is especially valuable when it is negative and raises doubts [4] (p.78-80).

Limitations

Blake and Mouton propose that Team Management leadership style is beneficial to all leaders, as every leader oriented to another style should strive towards it. James Scouller stated that the model does not fully address two important factors, the need of adapting behaviour, or style, according to different situations, nor the psychological factors of a leader. It is not always relevant for a leader to adapt team leadership, for example during a crisis, when the task is significantly more important than the interest of subordinates. Or when working in a tight timeframe with unexperienced team, therefore not having the time to instruct them properly and keep them involved [8]. A leader might find difficult to adapt the team management style because of inner phycological factors or personality, that is the characteristics of a leader, which is one factor the PMI standards say a major factor in a manager leadership style. Often a very efficient leader is significantly more skilled in areas not concerning people. Scouller states that it is just not sensible to imply that such a leader is not a good leader even though being very skilled in strategy, visioning, innovation, etc. [8]. The style that a leader reverts to under significant occasions, such as under pressure, tension or during conflicts, is hard to solve in a characteristic way [4] (p.31). There are definitely more aspects of leadership that could have been covered by the Grid, that are not [9]. According to the PMI standards a leadership style of a manager can change and evolve through time, which the Grid does also reflect, by suggesting improvements towards the Team Management style.

Annotated bibliography

The following are the main resources used for the construction of this article, and can provide basis for further and deeper studies on the topic.

- 1. Blake, R, and Mouton, J. (1985). The Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

- This is the third edition of the book that Robert Blake and Jane Mouton wrote about the Managerial Grid. The book discusses the Grid in great details. It presents the Grid framework, the five different leadership styles and examines the 9.9 orientation in great depth. The three additional leadership theories are discussed as well as how the Grid can be used to increase organisational effectiveness in a company. In addition, there is a conceptual analysis of current leadership theories as well as a research evaluating the validity of the 9.9 orientation.

- 2. Molloy, P. (1998). A Review of the Managerial Grid Model of Leadership and its Role as a Model of Leadership Culture. Aquarius Consulting.

- This article provides a more critical perspective of the Managerial Grid, other than what is displayed in the original book, as might be expected as it is written by the developers of the Grid. The Grid is described in a pretty detailed way, but the main focus of the article is to show the Grid as a OD process and as a model of leadership culture. The Grid is tested, with the main focus being on the longitudinally on Grid OD as a process.

- 3. Blake, R, and Mouton, J. (1981). The Versatile Manager: The Grid Profile. Homewood, Ill. : R.D. Irwin.

- This book is about the dilemma of managerial leadership, and it identifies behavioural principles that underlie organisational effectiveness and how to put them into use. It shows the Grid in detail, but it also describes in depth how important healthy communication is, especially with the subordinates. In addition, it deals with conflicts, confrontations and responsibilities, in a team setting and shared participation in general. Versatility refers to the capacity of a manager to solve a wide range of dilemmas, either regarding production or people, in a sound way.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition). Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/toc/id:kpGPMBKP02/guide-project-management/guide-project-management

- ↑ Harappa Learning Private Limited. (2020). Managerial Grid Theory of Leadership . Retrieved on 8.2.2021 from: https://harappa.education/harappa-diaries/managerial-grid-theory-of-leadership.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Molloy, P. (1998). A Review of the Managerial Grid Model of Leadership and its Role as a Model of Leadership Culture. Aquarius Consulting.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 Blake, R. and Mouton, J. (1985). The Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Clayton, M. (2017). ROBERT BLAKE & JANE MOUTON: MANAGERIAL GRID. Retrieved on 8.2.2021 from: pocketbook.co.uk/blog/2017/05/16/robert-blake-jane-mouton-managerial-grid/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Blake, R. and Mouton, J. (1981). The Versatile Manager: The Grid Profile. Homewood, Ill. : R.D. Irwin..

- ↑ Blake, R. and Mouton, J. (1985). The new Managerial Grid. p.1-2. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Scouller, J. & Chapman, A. (2020). Behavioural Leadership: Managerial Grid - Blake and Mouton. Retrieved on 18.2.2021 from https://www.businessballs.com/leadership-models/behavioural-leadership-managerial-grid-blake-and-mouton/.

- ↑ Islam, M. and Bhattachar, P. (2019). A Review on Managerial Grid of Leadership and its Impact on Employees and Organisation. International Journal of Research. 06. 159-162.