Benchmarking in Project Management

Nowadays, project management tools and methodologies have been highly useful for organisations that seek to implement changes in order to increase their performance. Adding to that, organisations are constantly striving to find new opportunities to make it as much effective for them as possible. One of these opportunities is to examine the outcomes and the lessons learnt from various similar projects that have been completed in the market from similar organisations and thus use benchmarking.

As a business term, benchmarking is the series of actions in order to compare one's business distinct processes, practices or procedures, to other businesses that perform similar activities and have a leading role in the world market. Benchmarking is mainly used so that the company gains valuable information in pursuance of improving its performance and, as a natural outcome, to increase its competitiveness. Usually, there are different indicators that companies use to assess their performance during the process of benchmarking that mainly focus on the aspects of time, cost and quality.

It has been proved that benchmarking against companies that have a leading role in the industry has effectively helped average organizations to improve their performance [2]. Based on that, this article will present how improvements in the performance of companies can be achieved by benchmarking projects. This article will firstly explore the general purpose of benchmarking. Then, it will be examined how the distinct types of benchmarking can be applied to the management of projects. Furthemore, there will be a discussion on what to benchmark and what aptitudes are needed to do so. Finally, an analysis about the limitations of benchmarking in project management will be held.

Contents |

Purpose of Benchmarking

Benchmarking is a constant process of analysis and research of the best performers in order to extrude useful information for improving the organisational or project performance of a company, and not just copy or imitate what others do to thrive. As Bent and Humphrey suggest about benchmarking, ‘‘Benchmarking is the technical core of the Total Quality Management (TQM) process. It identifies the quality of current personal skill levels and company procedures/methods, and then compares this quality with the latest state-of-the-art techniques’’ [3].

Another definition of benchmarking was suggested from the International Benchmarking Clearinghouse (IBC) Design Steering Committee which concluded in 1992 that benchmarking is: “A systematic and continuous measurement process; a process of continuously measuring and comparing an organisation’s business processes against business process leaders anywhere in the world to gain information which will help the organisation take action to improve its performance [4].”

It is clear from these definitions that benchmarking is not only a process in which performance, compared to others, can be measured, but also a tool to describe how notable performance can be accomplished. This kind of performance can be described by measures of performance indicators, called benchmarks. The activities that are used in order to achieve this performance are called enablers [5] and their main purpose is to analyze the logic for achieving this kind of notable performance. Usually, benchmarking studies are conducted with the support of this two components and thus it can be stated that benchmarks can be attained by obtaining enablers.

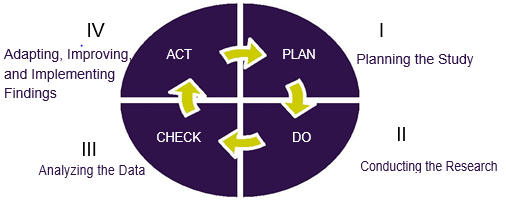

As part of the benchmarking process, many models and approaches have been used but they all take into account an iterative benchmarking process proposed by W.E Deming called the “Deming cycle”. The Deming cycle includes a minimum of four phases “Plan –Do-Action-Check” and is presented in Figure 1.

Types of Benchmarking

The types of benchmarking indicate what is compared when they involve comparisons that are closely associated with process, performance and strategic benchmarking. Apart from that, when they include internal, functional, generic and competitive comparisons, they are referred to whom it is compared against [7,8]. All these type of benchmarking are further analyzed in the table below.

| Types of Benchmarking | Definition |

|---|---|

| Performance Benchmarking | Comparison of performance measures in order to determine how good an organization is if compared to others. |

| Process Benchmarking | Comparison of methods and processes in order to improve the processes in an organization. |

| Strategic Benchmarking | Comparison of the current organization’s strategy with other successful strategies from organizations in the market.

This helps to improve competence so that the organization can cope with the changes in the external environment. |

| Internal Benchmarking | Comparisons of performance of departments inside the same organization in order to find and apply best practice information. |

| Competitive Benchmarking | Comparison made against the “best” competition inside the same to compare performance and results. |

| Functional Benchmarking | Comparisons regarding particular functions in an industry. The purpose is to master a specific function using this type of benchmarking |

| Generic Benchmarking | Comparison of processes against best process operators regardless the type of industry. |

Benchmarking Generations

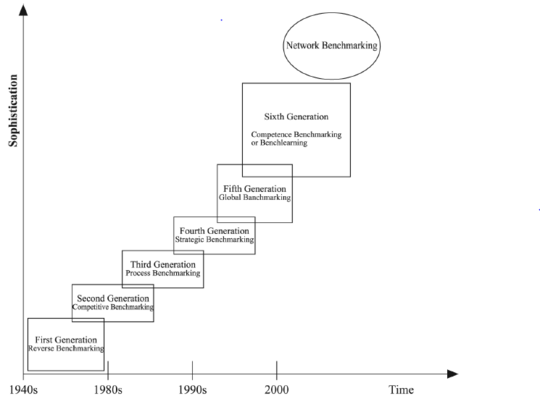

Benchmarking has been characterized as a developing science and thus many generations can be identified [9]. As it can be seen in Figure 2 the first generation of benchmarking, called “Reverse Benchmarking”, was entirely focused on the comparisons based on products' characteristics, functionality and performance with similar products, and thus it was more product-oriented.

Furthermore, the second generation, or as called “Competitive Benchmarking”, involved comparisons of processes with those of the competitors. The “Process Benchmarking”, which was the third generation of benchmarking, suggested that comparisons were developed outside the same industry. Adding to that, evaluations mostly had targeted companies with recognized strong practices, regardless of the industry and the competitors. The fourth generation is referred as “Strategic Benchmarking”, and is a systematic process of alternatives assessment, implementation of strategies and improvement of performance by trying to understand and adapt to successful strategies that external partners who participate in an ongoing business alliance use.

Strategic benchmarking is about trying to compare a competitor's strategy to one's own in the same market and product benchmarking compares the features and performance of actual products. As Gattorna and Walters [10] argue, unless the strategic direction of the addressed benchmark company is understood, it is improbable that any comparison will have successful outcomes, especially when management strategies of projects are concerned. Management performance falls under performance benchmarking but is influenced by the company's strategies. Benchmarking project management is a subset within the managerial performance indicators.

The fifth generation or “Global Benchmarking” has to do with a global development and application of benchmarking, and thus is dealing with the globalization of industries [11]. This generation of benchmarking is helping organisations to identify which are the best in class and then and link with them. As it was suggested by some researchers [12], some extensions of the model are starting to arise, and predictions about a sixth and a seventh generation called “benchlearning” and “network benchmarking” respectively are close on becoming a reality.

Benchmarking in Project management

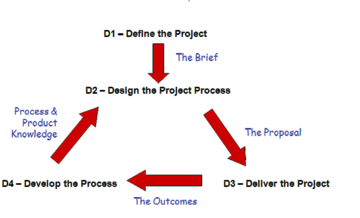

Improvement can be characterized as the primary driver behind any benchmarking initiative, including that of project management. As it can be seen in Figure 3, Maylor[13] presented the four distinct phases regarding the process of project management. The main idea behind “Develop the process” phase is that constant learning and improvement can be achieved by using information to improve the management process of any forthcoming projects, by evaluating the project progress and by learning from any previous experience. The improvement process can be divided into two parts. The first one is "learn by doing" and the second one is "learn before doing". As far as the project progress is concerned, tools, such audit reviews, lesson learnt during the project and scorecards are vastly used. However, benchmarking is used to link “learn by doing” and “learn before doing” with the aim of learning and improving managerial processes of any future projects.

Furthermore, benchmarking can be applied during different phases of a project for distinct purposes. For instance, when it is applied early on, such as in project authorization, it can be used to identify features that may be closely bonded with possible future problems. Adding to that, it can be used to identify aspects of project management (e.g. risk management) that require proper attention and precise handling so that the project leads to a favorable outcome. When applied during the project execution phase, it can be used as a useful project management tool that can guide decisions regarding the project. Finally, post-project benchmarking is mainly used in order to assess the performance of a project delivery system, to analyze the lessons learned during the project and to use feedback as a tool that can be used to enact benchmarks for future comparisons. Post-project comparisons are usually the first comparisons that organizations use. As the benchmarking process builds, they progress to its earlier uses as well. As time goes by, when satisfactory data are available, trends can be analyzed so that a clear vision into the performance of project management systems can be provided.

What to Benchmark

Benchmarking is a method of assessing the quality of a project’s management and learning from it for the management of future projects. Based on literature, the project manager is responsible for orchestrating the management progress of a project [14]. Therefore, and as it will be analyzed afterwards, the project manager should be endowed with certain skills and competencies to achieve superior results in project management.

As it was stated by the Project Management Institute [15], the effective project management should possess and master eight primary competencies. Competence can be defined as the knowledge, skills and personal aspects that bring about superior results or match performance standards [16]. Project managers are required to be highly effective people and possess knowledge of all the technical details of their jobs as well as the ability to get things done. So this eight primary competencies that should master according to PMI are: scope, time, cost, human resource, communication, risk, quality and contract management [15].

When the success of a project is to be measured, then the so-called ‘‘Iron Triangle’’ -which is recognized as the cornerstone of project success evaluation- is used (Fig.5). As Atkinson [17] states ‘‘cost, time and quality (the iron triangle) over the last 50 years have become inextricably linked with measuring the success of project management’’ [17, p. 337]. Atkinson claims though that these three factors will not signify whether the management of a project has been exemplary or not. He argues that these three estimations (especially time and cost) are put together at a time when the least amount of information is available regarding the project – typically in the planning stages.

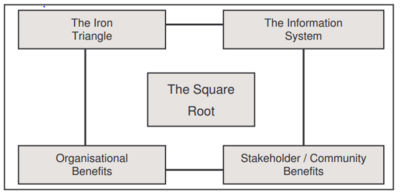

Figure 6: Atkinson's "Square Root" criteria for project management success

If the benchmarking process centres on these three criteria translated loosely as within budget, on time and to a prescribed quality then benchmarking the management processes will be flawed as well.

Apart from that, Atkinson [17] also suggests the adoption of the ‘‘Square Root’’ in order to create a more pragmatic view of project management (Fig. 6). He combines the three criteria of the iron triangle into a single touchstone and adds three supplementary criteria, which are information systems, benefits to the organisation and benefits to the stakeholder community. The attributes comprising each of the four components include both tangible and in-tangible elements, which would increase the difficulty of initiating a benchmarking process. For instance, information systems usually consist of maintainability, reliability, validity and information-quality usage. Benefits to the organisation pertain to improved efficiency, improved effectiveness, increased profits, strategic goals, organisational-learning and reduced waste. Whilst benefits to the stakeholder community refer to satisfied customers and users, social and environmental impacts, personal development, professional learning, contractors profits, capital sup-pliers, content project teams and economic impacts on the affected community.

Even though the scope of Atkinson's method is logical, substantial disaggregation will still be needed for benchmarking the management of a specific project.

As other researchers claim [18], the key areas of interest, when evaluating the management of a project, are effectiveness and efficiency. Efficiency can be defined as the maximization of the output for a given level of input while effectiveness is directed to the level of achievement of goals or targets.

As it can be seen then, there is a variety of sources and opinions on what to benchmark. Only if a common ground on what are the needed skills and competencies of manager is created, will benchmarking become generally acceptable. So far, the only agreement is on an agreeable generic benchmark evaluation of project managers' competencies.

Limitations

Benchmarking the management of projects has its own limitations that support the fact that is not always a good idea to introduce evaluation via benchmarking of project management. First of all, projects are by nature unique and have a specific life-cycle. Hence, it is difficult to find common ground among projects. The uniqueness of projects is mirrored in the way they are managed, which is something that increases the complexity to identify the best management practices among them.

Moreover, another limitation can be that benchmarking is lacking effectiveness when a problem that has not been previously recognized has to be encountered. If for instance a managerial aspect is facing a difficulty and the comparable partner has not experienced that kind of difficulty before, then it is most probable than a benchmarking process will not provide any feasible solution.

Furthermore, it is obvious that benchmarking is based on expense, meaning that it requires excessive time and cost of gathering and evaluating performance data. As a result, this can consume a vast number of resources and at the same moment wast a great amount of time. For example, the process of finding the right company to benchmark the right aspects of management can be time and money consuming. Adding to that, benchmarking is based on sharing knowledge and creating thrust among the distinct organizations which might in the end cultivate unwillingness to cooperate and raise suspicions.

Different factors and their interrelationships during a project can also be a limitation, and have a significant effect on its management. It is almost impossible to manage all of these factors during a large and complex project and thus it is crucial to separate the important few for the trivial many. This means that a manager should waste time to clearly identify the "key factors" that will have the greatest impact on the success of the project.

Finally, Benchmarking has often been found deficient because it highlights the performance gaps without giving the reasons for these gaps. Sometimes, the performance gaps identified through benchmarking have more to do with the differences in the way the organisations measure and track the performance of their systems, rather than any meaningful differences in the way each manager controls his or her project.

These so-called limitations can be offset somewhat by the benefits arising from benchmarking. Whereas audits and other forms of evaluation tend to occur at set points in time benchmarking can be a continual process that permits reciprocal benefits to both partners