Matrix Organizations

Contents |

Abstract

An organization can be defined as a group of people who work together in an organized way for a shared purpose [2]. The way an organization is structured can affect the amount of resources available for the organization as well as how different projects are carried out [3]. In the beginning of 20th century many organizations obtained their ways of working, either by structurizing their work with a larger focus on projects (projectized structure) or groups with similar roles and expertise (functional structure). In 1960s aerospace organizations saw a need of adopting a new approach that would combine the knowledge from various industries, and the third approach, called matrix organization, was found.

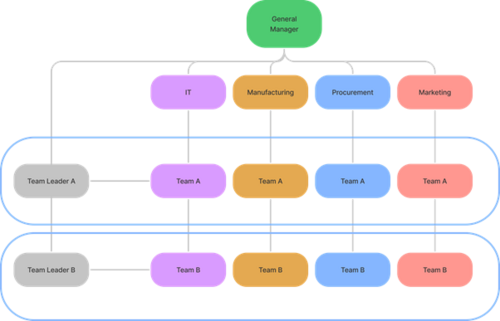

Project Management Institute defines Matrix Organization as any organizational structure in which the project manager shares responsibility with the functional managers for assigning priorities and for directing the work of persons assigned to the project [3]. This means that in matrix organizations there are generally two managers to report to, and the managers must collaborate for better resource allocation, as well as knowledge-sharing. Matrix organizational structure is commonly applied when an organization is focusing on projects and technical support across different functions and fields is needed [4]. An illustration of organization with matrix structure is shown in Figure 1.

Generally, there are three types of matrix organizations, based on the influence of each manager – weak matrix (stronger functional manager link), balanced matrix, and strong matrix (stronger project manager link). The project manager’s involvement in the activities determine the strength of the matrix organization.

Overview of matrix types and characteristics

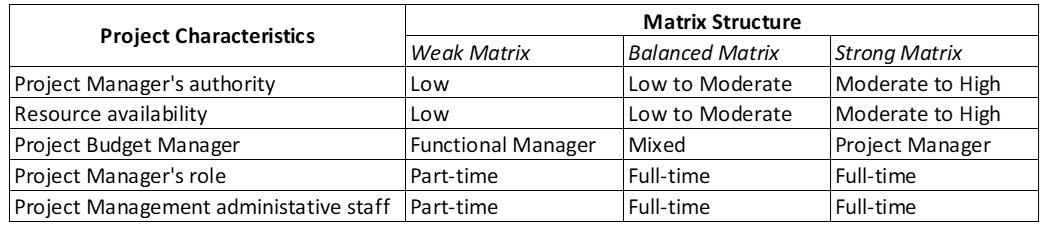

An overview of the matrix types and project characteristics is illustrated in Figure 2 [3].

From three types of matrix organizations, weak matrix has low project manager’s authority, and mostly the authority comes from functional management. Resource availability is low and the project’s budget holder is functional manager. Project manager’s role and their administrative staff is part-time.

When the strength of matrix is increased, project manager and their administrative staff work on with the team full-time. This means that their involvement in the project is increased, and most of their work revolves around this team.

Balanced matrix from its name implies that the strength between the project manager and functional manager is balanced. Both parties collaborate together, however, the functional manager still has higher control in the decision-making.

A strong matrix suggests that the project manager has the most authority over the project and its budget. Resource availability is also increased, from low-to-moderate to moderate-to-high.

Application

Matrix organizational structures are often complex and require managers that can oversee several units within the project. Moreover, the environment in which matrix organizations are applied successfully is unpredictable and complex, such as medicine or space industries [5]. According to Slack et al. (2016), matrix organizations require four main characteristics [6]:

- Communication between managers. All managers that are participating in the project development must communicate effectively for better decision-making and resource allocation.

- Management conflicts. A formal policy of managing conflicts must be developed to avoid confusion when a conflict arises.

- Committment. The project team must clearly understand why such structure is implemented in the organization and how it contributes to the development of a product or service. The team should be committed both to the project(s) as well as their own department.

- Role of project management. The project manager has a role of coordination which involves planning of the resources, budget, and time.

Strengths and weaknesses of matrix organizations

There are contradicting opinions on different strengths and weaknesses of matrix organizations. Research suggests that different authors can see the same characteristic of a matrix organization both as a strength and a weakness [7]. The main advantages associated with the matrix organizational structure includes efficiency, both in terms or resource allocation and information flow. Staff can be fully sourced to a project and also contribute to other parts of the organization, such as their functional department or other projects. The information flow is more transparent, allowing the organization to share the knowledge and see the progress of each functional team. Matrix organizations are also possessing stronger project characteristics, since the structure allows for better project management practices [8].

Because matrix organizations involve a lot of planning around administrative changes and staff resource allocation, the main disadvantage is the high administrative costs. However, if the matrix organization is mature, the additional overhead costs even out due to increase in efficiency [9]. The matrix organization involves a line and project reporting manager, which can potentially cause a conflict if the expectations and conflict management are not clearly defined [8]. This essentially can mean that staff must understand how the managers work together as well as how the reporting must be executed. Staff in matrix organizations can also work on several projects at the same time, causing disadvantage in understanding who to report to.

How to make the matrix organization work

References

W. G. Egelhoff and J. Wolf, Understanding Matrix Structures and Their Alternatives, London: Springer Nature, 2017.

D. Metcalfe, Managing the Matrix: The secret to surviving and thriving in your organization, West Sussex: Wiley, 2014.

R. B. Duncan, "Multiple Decision-making Structures in Adapting to Environmental Uncertainty: The Impact on Organizational Effectiveness," Human Relations, pp. 273-291, 1973.

L. C. Stuckenbruck, "The Matrix Organization," Project Management Quarterly, pp. 21-33, 1979.

Bibliography

- ↑ Moodley, D., Sutherland, M., & Pretorius, P. (2016). Comparing the power and influence of functional managers with that of project managers in matrix organisations: The challenge in duality of command. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 19(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v19i1.1308

- ↑ Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Citation. In Cambridge English Dictionary. Retrieved February 11, 2022 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/organization.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), Fifth Edition ed., Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, Inc., 2013.

- ↑ Kuprenas, John A. Implementation and performance of a matrix organization structure. International Journal of Project Management 21 (2003), p.51-62

- ↑ Burton, R. M., Obel, B., & Håkonsson, D. D. (2015). How to get the Matrix Organization to Work. Journal of Organization Design, 4(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.7146/jod.22549

- ↑ Slack, N., Brandon-Jones, A., & Johnston, R. (2016). Operations Management (8th ed.). Pearson Canada.

- ↑ Goś, K. (2015). The Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Matrix Organizational Structures. Studia i Materiały Wydziału Zarządzania UW, 2015(2), 66–83. https://doi.org/10.7172/1733-9758.2015.19.5

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cristóbal, J. S., Fernández, V., & Diaz, E. (2018). An analysis of the main project organizational structures: Advantages, disadvantages, and factors affecting their selection. Procedia Computer Science, 138, 791–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.103

- ↑ C.J. Middleton, “How to Set Up a Project Organization,” HBR March–April 1967, p. 73.