Concurrent Engineering

Written by Helena Svendsen

Contents |

Abstract

The implementation of concurrent engineering in a project management framework will be explained holistically in this article. As concurrent engineering in its nature is highly dependent on the successful collaboration between the project’s organizational parties, this article will look into the following three aspects: the people participating in the project, the project process itself, and the technology and/or tools required to achieve these. The article will focus on how to make the implementation of concurrent engineering approach successful by addressing topics like the value of knowledge sharing, the necessity of interdisciplinary teams, effective project planning and what tools are required to support these processes. Finally, the approach's advantages and disadvantages are discussed, and lastly they are paired with the preceding sequential engineering approach to address the situations in which one approach is better to apply than the other.

Big idea

Context

Concurrent engineering (CE) emerged in the 1980s as a result of the need for a more integrated method of operation to keep up with growing competition in the market, respond to a shorter product life-cycle, and meet shifting market and customer demands[1]. Concurrent engineering was thought to be a potential answer to the issues faced by businesses at the time, in order to help them create cheaper goods that could be supplied faster and have higher functionality [2]. Concurrent engineering functioned as a direct response and opposite to the previous traditional "over the wall", sequential engineering (SE) approach, with the overall goals of higher productivity and lower costs by shorter development time and shorter time-to-market.

“Concurrent Engineering is a systematic approach to the integrated, concurrent design of products and their related processes, including manufacturing and support. This approach is intended to cause the developers from the outset to consider all elements of the product life cycle from conception to disposal, including quality, cost, schedule, and user requirements.” - Winner, R.J et al. (1988) [3]

What is Concurrent Engineering?

Concurrent engineering (CE) is neither a technique nor a tool. It is a manner of thinking that calls for a wide range of techniques and methods. The execution of a project's processes simultaneously with the participation of both upstream and downstream functions over the course of the project's life-cycle is the very essence of concurrent engineering [4].

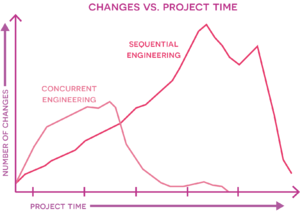

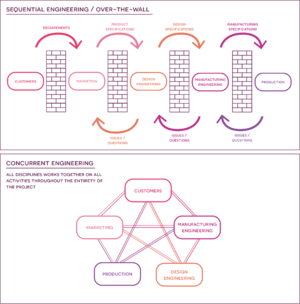

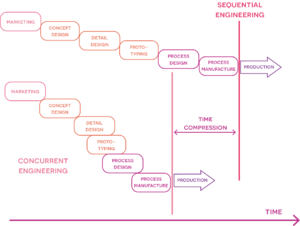

The approach aims to decrease the number of larger iterations further down in the process, where the impact is much greater, by encountering and solving them as they appear in the earlier phases of the project (figure 1) . This is made possible by the concurrent nature of the approach, in which integrated, multifunctional teams collaborate and work together simultaneously to address multiple project-related issues at the same time. As the control and responsibility is shared amongst the departments across the project’s phases, and because their activities overlap, they are able to identify potential problems as they appear and are able to address them faster[5]. This is opposite to the traditional sequential engineering (SE) approach, where each activity is handled by one functional organization at a time (marketing, design, manufacturing etc.) and then thrown “over-the-wall” to the next organization (figure 2) without communication. The problem with this approach is that it might be in the very late stages of the process that a problem is identified, because of the lack of communication between organizations, which will result in the activity/product being sent back over-the-wall to fix the issues [6] resulting in a prolonged process time and increased costs. By working concurrently the overall project duration is greatly reduced, as there is constant collaboration and iterations between the teams in the process, ensuring that larger and time-consuming issues will not occur in the final stages, when changes can be both costly and time-consuming. The reduction in time for CE compared to the sequential approach can be seen in figure 3 . And the benefits of the implementation of CE in a project setting can also be deduced from the figure, as it results in an increased productivity and an overall lower cost of the project due to the reduction in duration[5]. Which also means that the time-to-market for the potential product or service is also decreased, providing the company with a competitive advantage on the market compared to their competitors.Application/Implementation

The concurrent character of the approach makes CE essentially a socio-technical concept[4]. As previously stated, it calls for close coordination and communication across the project's many phases and disciplines. Since effective stakeholder communication, their willingness and ability to collaborate, and the support of tools and communication technologies are crucial components to support and sustain a CE project management strategy, the primary requirements for a successful concurrent engineering project are also related to these elements. These elements can collectively be classified as a company's organizational system, which is a holistic framework in which individuals carry out processes with the aid of tools (methods, tools, or technologies) in order to achieve specific objectives within the organization and/or project environment [7]. To better address the essential elements of the framework and what is needed when attempting to implement the concurrent engineering framework in a project management scenario, the following sections will explain these three aspects: People, Process, and Technology/Tools.

Process

Some key aspects for CE is to have a well-defined process with clear ownership and defined goals. That includes:

- Considering and planning overlapping of activities

- Ensuring that ownership of the process occurs

- Defined, clear and quantitative goals

Overlapping activities

Defining the process, creating the corresponding schedule of activities, and deciding how to handle the necessary overlapping activities are the first steps in adopting CE. For the project to be completed most effectively and efficiently, this includes how and when the tasks should overlap and where all risks are taken into account early in the process. When there is strong communication and cross-disciplinary teamwork, overlapping activities have been found to shorten development time, but there is also evidence that it is not always advantageous for project governance[6]. This can occur if there are two or more overlapping operations, in which case modifications in the upstream activities necessitate significant changes in the downstream activities, which have already been finished as a result of the overlapping. Therefore, in order to minimize the number of actions that need to be redone, it is crucial to take into account which activities are overlapping and that the downstream impact is taken into account prior to planning overlap.

Ownership and defined scope

Since absence of ownership equates to a lack of project discipline, a process owner must be appointed for the CE process. When an issue arises, the team must be able to turn to the person in charge for guidance. The primary responsibility of the process owner is to ensure that the CE process is correctly implemented and updated as needed. Having a process owner ensures better reactivity to impending changes and better learning for future process improvements, since a process owner is responsible for both the full process and the linked sub-processes[6]. However, for the process owner to be successful in implementing CE, there must be set forth, explicit and measurable project goals. In order for the project team to have a shared knowledge of the objectives when working simultaneously on the project, the scope must be precisely specified. This will help to reduce misconceptions as the project progresses.

People

A few factors must be taken into account for a CE deployment to be successful. They are all connected to the cooperation between the project's participants and serve as requirements that must be fulfilled or considered before starting a transition or the implementation of a CE strategy for a project:

- Need for close communication between team members

- Choosing specialists or generalists

- Need for multidisciplinarity

- The role of the project manager in a CE setting

Communication

A few prerequisites must be met for a CE team to succeed in order for the project to get off to the best potential start. These requirements suggest that an effective team should have no more than 10 members, and that each member must choose to work on the project of their own free will and be driven by their intrinsic motivation to continue working on it until completion [5]. In addition, for the team to be able to successfully execute the project, it must have at least one representative from each of the major disciplines involved. Since strong communication between the phases/disciplines is necessary to reap the benefits of a CE strategy, it is crucial to keep this in mind before embarking on the project since this might necessitate some changes to function properly.

This includes colocation [5], in which the project team is physically situated in close proximity to one another. This has demonstrated to considerably enhance both problem-solving and decision-making since they have constant access to both the people and the information related to the project. By physically putting the team members close to one another, they are more likely to talk about issues and assist one another in solving them. It also helps to strengthen the team's bond by ensuring that the group views itself as a team rather than a group of individuals sharing knowledge, which in turn strengthens communication [8]. Due to the overlapping nature of CE, the team members' sensitivity [5] to each other's tasks, is also an important factor in the need for communication. For example, if one team member is working on an upstream task, the other team members are highly sensitive to the outcome of that task because it affects their downstream tasks, and as a result, they are more eager to keep each other updated to streamline the process.

Emails are a common method of communication in organizations as they allow for more effective message distribution, but this does not guarantee that the messages will be read, comprehended, or taken into account. Because of this, true face-to-face communication is still the best method for exchanging information and receiving prompt, precise responses [8]. Therefore, colocation is crucial when employing a CE approach because it has been shown that having direct access to one another and being able to solve issues quickly reduces misunderstandings and delays in the project process.

Specialists vs. generalists

When assembling a CE team, the question of whether experts or generalists are required more often comes up[8]. Since it is challenging to keep the specialists working on the project full-time, they are only present when their expertise is required. As a result, they do not share the same dedication to or sense of responsibility for the project as the other team members. Additionally, because they may not typically work in a CE approach, they are unable to understand how their effort would affect downstream processes, which could lead to further delays. On the other hand, generalists are able to dedicate their whole attention to the project and serve as an all-around speciality team member. Some businesses, particularly those involved in development, will prefer generalists over specialists when working with CE because they will operate as a part of the team throughout the project's life-cycle, which is more crucial than having a specialist. For some businesses, the requirement for a competitive advantage frequently rely on the skills that the specialists offer, and for them, the demand for special skills outweighs the need for a closely working team, which could make adopting CE more challenging and complex.

Multidisciplinary teams

Project manager

Technology/Tools

Need for communication and collaboration makes new technologies a necessity to allow for information sharing

Implementation approach

When is it applicable? How to implement? When to implement?

Benefits & Limitations

Benefits:

Shorter time-to-market - compared to SE

Possible to make changes/alterations early on - focus on solving the issues in their early stages/as they appear in the beginning, so they will not have such a high impact later on

minimized risks of loss (time and knowledge between departments/tasks)

Limitations:

Need for close collaborations between departments

Maybe do a table to compare CE and SE? - Benefits and limitations

Concurrent vs. sequential engineering When to choose one or the other?

CE: no need for a defined output (only scope) in the beginning - SE: need for at defined goal/output

Bibliography

Concurrent Engineering in the 21st Century: Foundations, Developments and Challenges

The newest advancements and industry-best practices for the guiding principles of the framework are covered in-depth in this book's presentation of concurrent engineering. It delves deeply into CE procedures and practices, as well as practical applications and experiences. The book offers a thorough overview of CE from many different viewpoints and industries since it is a compilation of research by numerous professors and scholars.

References

- ↑ Trygg, L. (1993). “Concurrent Engineering practices in selected Swedish companies: a movement or an activity of the few?” in Journal of Product Innovation Management, 10(5), pp. 403–415. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0737-6782(93)90098-B

- ↑ Clark, K.B. & Fujimoto, T. (1991). Product development performance: strategy, organization, and management in the world auto industry. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

- ↑ Winner, R.J. et al. (1988). The role of concurrent engineering in weapons system acquisition. IDA R-338. USA: Institute for Defense Analyses.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stjepandić J., et al. (eds) (2015) Concurrent engineering in the 21st Century: foundations, developments and challenges. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Swink, M.L. (1998). “A tutorial on implementing concurrent engineering in new product development programs,” in Journal of Operations Management, 16(1), pp. 103-116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(97)00018-1.'

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bhuiyan, N. et al. (2006). “Implementing Concurrent Engineering” in Research-Technology Management, 49(1), pp. 38-43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2006.11657357

- ↑ Boer, H & Krabbendam, JJ (1993). Inleiding organisatiekunde (Introduction to organisational science). University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Smith, P.G. (1998) “Concurrent Engineering Teams,” in D.I. Cleland (ed.) Field Guide to Project Management. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 439–450, chapter 32.