Metrics in Portfolio management

Contents |

Abstract

According to the Project Management Institute (PMI), a metric is a "description of a project or product attribute and how to measure it" [1]. It is, indeed, a quantitative measure of performance or outcome that provides a basis for comparison, evaluation, or improvement.

Peter Drucker famously said, "if you can not measure it, you can not improve it". However, it is not enough just to measure. The ultimate purpose of metrics is, as well, to provide the right information to the right person at the right time, using the correct media and in a cost-effective manner [2]. Notably, building effective metrics is extremely relevant when it comes to decision making at all levels of a company, project or portfolio. Thereby, knowing specifically what to measure when it comes to portfolio management is a must to ensure the future of the organization.

The purpose of this article is to describe the type of metrics needed to evaluate Portfolio performance and outline their differences from the well-known metrics to measure Project performance. Firstly, this article will focus on introducing to general terms. Secondly, the relevant role of the portfolio management will be highlighted. Hereafter, what is needed to create an effective metric will take part in this essay. Lastly, different useful metrics and techniques for portfolio management will be listed and explained in detail.

General terms

Firstly, to understand the topic under study, both the basics of Portfolio Management and Metrics need to be introduced.

Portfolio Managements

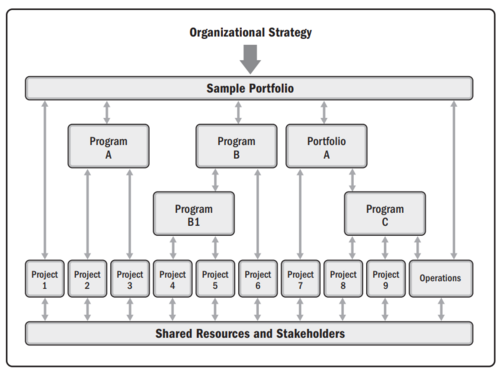

As the PMI states [1], portfolio is a collection of projects, programs, subsidiary portfolios, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives. Notably, those programs or projects within a portfolio may not be directly related or interdependent, they are linked to the organization’s strategic plan by means of the portfolio.

Beisdes, portfolio management is a crucial organizational capability that enables organizations to effectively manage and balance their portfolio, align projects with their overarching strategy, and ensure the allocation of resources in order to maximize benefits [4]. The PMI [3] offers a broader definition and, additionally, points out how portfolio management seeks for this alignment between the portfolio components and the organizational strategy: selecting the best portfolio components prioritizing the work, providing the needed resources, overseeing or working with portfolio component managers on their implementation, supervising proper transition into the operational environment, and enabling the achievement of portfolio value. Furthermore, Harvey Levine in his elaborated Project Portfolio Management Guide [5] mentions what portfolio management definitely is not: the error lies in assuming that it is primarily concerned with managing numerous individual projects, but this is not accurate. The real focus of portgolio management is to manage the collection of projects as a whole, with the aim of maximizing their overall contribution to the overall welfare and success of the enterprise.

Although portfolio management is tailored by and for each organization, there are many common elements and approaches. Indeed, portfolio management aids in decision-making across the full range of project portfolios through the following four steps [4]:

- Gathering data from existing and proposed projects,

- Arranging and categorizing the data,

- Presenting the data to a carefully chosen decision-making team for comprehensive portfolio evaluations, and

- Establishing a framework for communicating and executing decisions.

Metrics

The simplest definition of metric is the one stated by Cambridge: "system for measuring something" [6]. Even though it turns out to be a poorly detailed definition, it lays the foundations of what a metric does. In fact, the core metric function is to measure something. What is being measured and why these measurment are taking place are the components that make metrics relevant. Looking deeper, metrics are tools of quantitative evaluation that can be utilized for the purpose of monitoring and measuring performance or success. At the business or company management level, metrics become even more relevant when they are aggregated to a set of metrics to construct a dashboard that management or analysts regularly consult to ensure that performance assessments and business strategies are maintained.

Metrics require a need or purpose and, not least, they need a target and/or baselines as reference points. On the one hand, it is necessary to specify what is intended to be measured in order to determine why this metric have to be conceived. On the other hand, targets need to be defined. If there is no point of comparions, what is going to be measured against? The metric would not have a raison d'être [2].

Roles and responsibilities of a portfolio management office

As the Portfolio Standards of PMI state [3], Portfolio managers have the responsibility for the establishment and implementation of portfolio management. Among other contributions, the Porfolio Management Office (PMO) supports the portfolio management by:

- Identifying, analyzing, coordinating, negotiating, monitoring, and controlling portfolio components; supporting component proposals and evaluations; facilitating prioritization; authorization; termination of components; and facilitating the allocation of resources in alignment with organizational strategy and objectives.

- Coordinating communication across portfolio component.

- Providing program and project progress information and metric reporting utilizing key performance indicators (KPIs) (e.g., expenditure, defects, resources) to the portfolio governance process.

Evidently, the Porfolio Management Office (PMO) generally establishes the metrics needed to validate the performance of the overall portfolio of projects. To be effective, the PMO needs to define the success metrics that are going to be used to determining how well each project and the overall PMO organization is delivering value within and across the performance domain framewok. The PMO might also want to weight each Performance Domain (PD) in terms of how important it is in determining the PMO’s (and each project’s) success. Each metric should directly align with each domain’s intended outcomes to support efficient oversight. [7]

The current eight performance domains are:

- Stakeholders (relationship, engagement and expectation management)

- Teams (health and performance)

- Development Approach & Life Cycle (process of building)

- Planning (defining what needs to be done)

- Project Work (assignments and tasks)

- Delivery (deploying the project into operations/use)

- Measurement (ways to quantify, monitor and track progress and outcomes)

- Uncertainty (identifying and mitigating risk/dealing with unknowns)

According to Harold Kerzner [2], the PMO should address three crucial inquiries, including:

- Whether the company is engaged in the proper projects, which entails determining if the projects align with strategic objectives and support strategic initiatives;

- Whether the company is involved in a proper number of appropriate projects to maximize investment and shareholder value; and

- Whether the company is executing the proper projects in the right manner, which involves assessing project completion time and cost.

Notably, the term "proper" is present in all three questions and significantly implies a sense of value.

Effective metrics

Gold rules

Efficient use of time and resources is crucial in portfolio management, and progress measurement is no exception. Consequently, it is relevant for portfolio managers to point to the development of metrics that only measure relevant and useful insights for decision-making. According to the PMI Standard [1] and George T. Doran [8], the SMART criteria is one of the golden rules to be followed in order to create effective metrics. Specifically, the acronym SMART stands for:

- Specific: Measurements are specific as to what to measure. define what you are going to accomplish answer the What is measuring

- Meaningful: metrics ought to be linked to the business case, baselines, or requirements. Evaluating project achievement that do not contribute to meeting objecvives or enhancing performance is ineffective. Besides, metrics' meaningfulness is commonly related to their nature of being quantifiable or "measurable" against the baseline and stated requirements.

- Achievable: it is meaningless to establish unfeasible or out-of-reach targets. Targets defined need to be attainable given the people, technology, and environment considered.

- Relevant: the information provided by the measure should represent value and allow actionable information.

- Time-bound: metrics have to be associated to an specific time frame. Creating these boundaries allows to keep the measurements on track and accountable.

Value based metrics vs. Traditional metrics

In 1996, Norton and Kaplan introduced the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) [9], a tool that already expanded beyond the traditional financial metrics to include non-financial metrics. The Balanced Scorecard framework aims to achieve desired outcomes aligned with a business's strategy. This includes creating value for present and future stakeholders, as well as leveraging internal capabilities and investments in people, systems, and procedures to improve future performance

Later in time, "Project Management Metrics, KPIs, and Dashboards" was presented by Harold Kerzner [2]. It highlights the key differences between traditional metrics and value-based metrics and explains how each type of metric can be useful. It is argues that traditional metrics are useful for tracking project performance and ensuring that it is completed within the constraints of the triple constraint model (time, cost, and scope) called Iron triangle. However, these metrics may not necessarily provide a comprehensive view of the projects' overall value to the organization.

On the other hand, value-based metrics are centered on the strategic objectives and intended benefits. They help to ensure that the projects are aligned with the organization's strategic objectives and that it generates the expected benefits. However, value-based metrics may be more difficult to measure and track than traditional metrics. The definition of value and how it is measured can differ depending on the industry, company, and the characteristics of the business. Different stakeholders may have their own ideas of what value means to them, such as job security, profitability, reputation, or the creation of intellectual property. It can be challenging to meet the needs and expectations of all stakeholders at once

Notably, while traditional metrics have as primarily audience the project manager and the team, value (or value reflective) metrics are more useful for the clients/stakeholders.

The importance of the value component in the definition of success cannot be overstated. When management makes poor decisions managing project portfolios, companies end up working on the wrong projects. For example, the deliverable requested can be produced but either there is no market for the product or stakeholders may be displeased with management’s performance.

In any case, Kerzner suggests that the use of value-based metrics and traditional metrics in combination can provide a more accurate and comprehensive assessment of the project's performance. While the traditional metrics can be used to monitor the performance of the project and ensure that it is completed within the constraints of the triple constraint model, the value-based metrics can be used to measure the project's overall impact on the organization and assess its contribution to the organization's strategic objectives.

Regarding assesment and management at porfolio level, value-based metrics clearly gain greater importance than traditional ones: portfolio success have to be defined in terms of the value that was expected to be delivered.

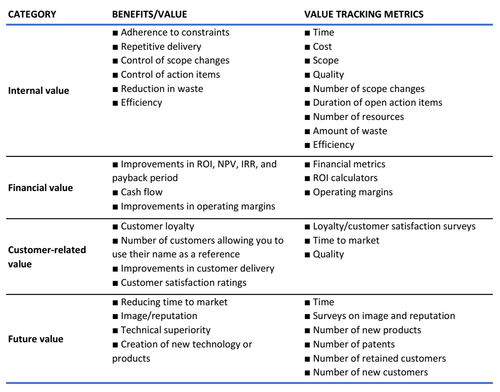

Portfolio measurement techniques and metrics

Portfolio managers should decide what to prioritize between all the opportunities (projects) since the resources are not unlimited. As it was mentioned previously, the PMO pursues the strategic objectives of the company and success is defined in terms of value that is expected. Thereby, projects in portfolio have to be selected that can maximize the value, based on the given constraints placed on the available resources. In order to do this, PMO are required to queantify value. Specifically, Kezner [2], defined four main value categories (internal, financial, customer-related and future value) and their associated tracking metrics. These four categorias have a strong relationship with the performance perspectives considered in the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) [9].

Kezner value categories:

- Internal value

- Financial value

- Customer-related value

- Future value

Aplications

Case of study 1: Portfolio management system at Crompton Corporation

Case of study 2:

Limitations

It is relevant to note that advances in project metrics have been rapid, but advances in portfolio metrics have been slow because not all companies maintain a project management office (PMO) dedicated to portfolio management activities. This leads to changes in the role of the project manager, the metrics used, and the dashboard displays [2].

TO BE COMPLETED

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Project Management Institute (2021) <<Project Management: A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge and The Standard for Project Management>> PMBOK guide 7th Edition

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Harold Kerzner (2017) <<Project Management Metrics, KPIs, and Dashboards>>, Wiley & Sons

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Project Management Institute (2017) <<The Standard for Portfolio Management>> 4th Edition

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 G. Levin & J. Wyzalek <<Portfolio Management - A strategic approach>> Taylor & Francis Group

- ↑ Harvey A. Levine (2005) <<Project Portfolio Management - A practical guide to selecting projects, managing portfolios, and maximizing benefits>> Jossey-Bass

- ↑ Cambridge dictonary, Cambridge University Press & Assessment 2023

- ↑ Michael Wood (2021) <<Are You Effectively Measuring the Right Success Metrics?>> Project Management Institute

- ↑ Doran, G.T. (1981) <<There's a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management's goals and objectives>>

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996) <<The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action>> Harvard Business School Press