Project based organisations

developed by Josefine Steinfurth

This article presents the theory of project based organizations (PBO's). The Project Based Organization is an organizational structure that supports project driven businesses. The functional organization is presented as a comparison to the PBO in order to better understand the problems it solves. The PBO is a structure which is organized according to projects instead of functional units. This gives the project manager high authority and responsibility for the success of projects, making project, program and portfolio management highly important to practice competently. The advantages of the PBO are that they are work well in complex and dynamic environments with high uncertainty and risk. Additionally the PBO is advantageous when working across multiple organizations or with external clients. The article proceeds to present a suggestion for strategies to implement an PBO structure, suggesting to start on experimental one team basis. Then the main limitations within PBO's are presented. The key limitations are lack of knowledge sharing and organizational learning across multiple projects, as well as coherence throughout the organization and to senior management, creating problems with effectiveness and support. Lastly the article presents the limitations of application of the PBO structure. The main limitation when applying the theory of PBO's is that it requires a restructuring of an organization, which is a huge task. Furthermore, the theory behind the PBO that one needs to build the application upon, is complex and goes across several research domains. It is therefore a resource heavy theory to apply in practice.

Contents |

Introduction

In recent years more industries are moving towards project based approaches [1]. The traditional way of organizing development is rigid in its structures leading to problems in execution of new and innovative initiatives. This is because the organizational structures inhibits the flexibility necessary to develop in a dynamic environments, and inhibits the flexible nature of projects [2]. This has lead researchers and practitioners to looking at ways of organizing in a more flexible manner; projects. The film industry is a classic example of an industry that has historically been working project based [1] [3] [4]. This way of working has reached increased attention in other industries in the last couple of decades, where Michael Hobday's work on Project based organisations[5] has been a key source of inspiration for many researchers to build on [3] [6] [7][8][9][10].

This article will give an overview of Project Based Organizations (PBO's). The article will first present the big idea; the characteristics of PBO's, how they solve the problems that occur in the traditional organizational structures. It will present and an overview of the PBO comparing it to the traditional functional organization structures as well as give perspectives on how Project, Program and Portfolio management relates to the PBO. It will present an application of the PBO; what strategies exist for transforming organizations and which steps to take to enhance the specific values that a PBO structure brings. Lastly the article will present the limitations of PBO's, both giving an overview of the limitations inherent to the PBO, as well as limitations in application.

Big Idea

What are Project based organizations?

The Project Based Organization is an organizational form that attempts to create a system that favors the dynamic and flexible environment of projects.[2] [4] To better be able to understand the PBO an introduction of its opposite; the traditional functional organization, is necessary.

The functional organization

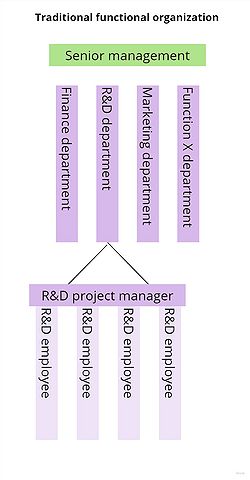

The traditional functional organization, is an organizational form which is structured in functional units (departments) each specialized within a certain domain. Classical examples of departments are; R&D, Finance, Marketing etc.. [11] The structure of the functional organization is illustrated in figure 1, where it can be seen that the departments all run parallel to each other with no links in between. Each department refers to the Senior management, who are in charge of creating the objectives of the organizations' vision and strategy. [2] [11] The head of each department thus have to make sure that initiatives within their own department align with the strategy and vision to keep the support of Senior Management.[12] This is often done through structured documenting practices and well defined formal procedures, such as reporting.

The parallel running departments in the functional organization creates silo systems, that makes this type of organization well suited for repetitive operations with small incremental changes. However the structure becomes problematic if the organization introduces a high rate of projects.[4] This is because there is little range for flexibility or cross domain collaboration in such silo structures. In a functional organization, a project and therefore project manager (PM) would be underneath a head of department in the organizational hierarchy. The role of the PM is therefore often mostly coordination and only little decision making, as this lies with the head of departments. If a project needs collaboration across departments, the manager would thus have to refer to, and ask permission from all department managers before making decisions. This creates high control for the head of departments yet low control for the project manager. This leads to problems in project progress due to low flexibility and authority, with the project manager. It leads to poor communication internally in the project team and with external partners, because the PM can rarely answer urgent questions immediately as they have to ask for permission from each department manager. This leads to frustration for the PM and lack of confidence in the PM with the project team and client. For the above mentioned reasons it becomes difficult to execute innovative and experimenting initiatives, with high uncertainty and risk, as well as projects that need competences across specializations in a functional organization. [2] [4]

The Project based organization, attempts to solve these issues of cross collaboration and flexibility. [13] [4]

The project based organization

The Project Based organization attempts to create a structure that favors the dynamic and flexible environment of projects. The Project Based Organization (PBO) is an organizational structure where[4][2][13];

- projects are the main driver of business

- the project manager has high control over functions and resources

- the flexibility inherent to the structure enhances the ability to be proactive towards uncertainty and risk

- organizational openness enhances collaboration with external partners making it easier to be proactive toward e.g. client uncertainty

These 4 characteristics will be elaborated further below.

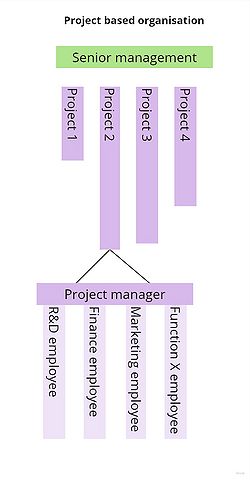

1. Project based organizations are driven by projects.[4] Figure 2, illustrates how projects run parallel to each other and are the main driver of the business instead of the specializations that lie in the departments as seen in the functional organization. The functional units, i.e. R&D, finance, marketing etc. are integrated in each project in the PBO by gathering a team of employees with different specializations. Furthermore, when working project based contrary to function based the knowledge and capabilities are created and build throughout the project. [14] This means that project based organizations requires that the employees not only know their specializations but also have the competences to acquire new knowledge and capabilities [9]. However, employees will only have the project to work on, and therefore do not have to prioritize between operational and project work. This frees up time and mental space for building these capabilities. [2]

2. The project manager is the main responsible for execution and decision-making in the projects that run in the organization. This means they have high control over all functions of the projects including resources, with only senior management to refer to, as seen in figure 2.[2] Because of the integration of specializations the project manager does not have to try to build collaboration across rigid departments as seen in the functional organization. Instead the PM is given high authority over the project. One of the mechanisms behind this is that the controlled step of referring to the department heads is eliminated. The simple link from PM to senior management is the key to agility and flexibility that is inherent to PBO's. [7]

3. Due the above described structures and the authority that lies with the PM, the PBO has the ability to deal with fast change as well as being proactive to uncertainty and project risk. The project manager, has the power to make the necessary decisions to urgent problem, and have a better standpoint for negotiations. [13] [7] This characteristic of the PBO stands in contrast to the functional organization where the project manager would not have the authority to make proactive decisions. [2]

4. One of the ways of dealing with complexity is stakeholder engagement.[15] The authority of the PM is an advantage when working with external partners and working across several organizations, because it leads to an organizational openness.[13] This is because the point of contact is reduced to just the PM, instead of the PM and a number of other departments cf. characteristic described above. [2] This organizational openness makes it easier to include external stakeholders and bring them close to the project process. [13] The enhancement of communication this brings leads to a PM that can ensure that external partners are properly informed, and even part of decision-making processes throughout the project, often leading to higher satisfaction with the client. Thus the PBO becomes an enabler for co-creation in projects. PBO's are therefore beneficial when dealing with complex project where the clients' needs may change through the progression of the project as they gain more knowledge. [2]

The PBO in theory and practice

According to the PMBOK Guide 2021 a project is " [...]a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result."[16] The definition refers to uniqueness, and even though not all standards agree on this factor, it can still be concluded that projects are often different and need different types of structures to support them and to get the best results. [17] Thus, because PBO's are driven by projects the organization can look very different both from organization to organization, but also from project to project within the PBO.

Project to project variance in the PBO

The PBO creates temporary organizations each time a new project is initiated. This means that the objectives of the project will partly define the organizational structure within that project. For example; the level of complexity or innovation of the project will have an impact on; the size of the project, the amount of stakeholders involved, the uncertainty of the project etc. These are all factors that will influence the temporary organization that is created when initiating a project.

Another factor that will influence the project is the contractor or client of the given project. These will often have different needs and requirements for the project and its collaboration or partnership structures, thus shaping the communication structures of the project. This is exactly the benefit of PBO; they are so flexible that they can adapt to the given context of the project; they can adapt to the best possible way of operating with the specific client, project team, project content, project complexity etc.

Organizational context of the PBO

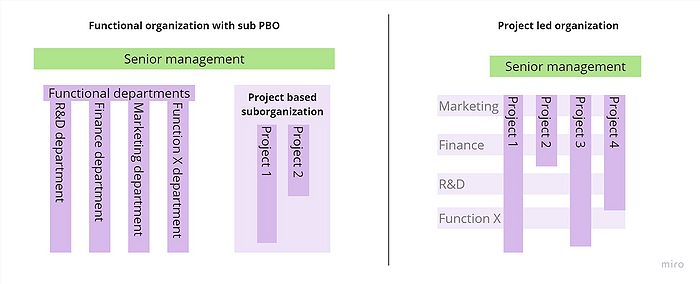

The PBO can as mentioned also look different from organization to organization. The "pureness" of the PBO can be altered, to fit the organizational needs. In some industries it is possible to create more or less pure PBO's. The classic example is as mentioned the film industry. [1] [3] However, a PBO can also exist within a functional organization as a sub organization as shown in figure 3. [13] [4] Lastly, the PBO can exist as a so called Project Led Organisation. This is the most common form of the PBO in practice. It has weakly linked functional units that run across the projects, helping to create coherence between the individual project in the organization, but keeping the main decision authority with the PM.[3] [2] [13]This structure is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Left; The PBO as a suborganization in a functional organization. Right; Project Led Organization (Created by J. Steinfurth)

Summing up, the PBO is a project driven business and therefore changes with its environment. It is capable of doing so because of its flexibility and the authority that lies with the PM, creating an open organizational structure and a proactive approach towards uncertainty and risk. The authority that lies with the PM is thus a positive characteristic of the PBO. However, with the authority follows a responsibility. Therefore good management, and especially good Project, Program and Portfolio management, is of vital importance for success in such organizations.

Project, program and portfolio management theory in the PBO domain

The following paragraph will help give an overview of the relationship between the PBO and Project, program and portfolio management (PPPM).

PBO's operate in two distinct levels of activities; the organizational level and the project level. [9] [18] These levels are represented in figure 4; The strategy and business models are developed on the organizational level (green), and the activities at Project, Program and Portfolio levels should support that strategy (purple). [19] This relationship between the organizational level and project level is further described in the PMI standard, where strategy implementation is one of the main activities of portfolio management and where defining program outputs that support organizational strategy is one of the main activities of program management. [20]

In the context of the PBO, the project manager becomes the link and enabler of the strategies developed on organizational level, to integrate them on project, program and portfolio level. This is illustrated as the arrows in figure 4. Researchers suggest that the PBO framework even enhances the effectiveness of project portfolio management, because of the authority of the PM. [7] [17] This shows the importance of both the PBO structure and PPPM and the reciprocal support which is found between the two levels, where one cannot succeed without the other. It also shows that PPPM practices are the tools that PM's utilize to support and drive the effectiveness and thus success of the projects, programs and portfolios within the PBO. [4] [7] It has now been established that project, program and portfolio management is important for organizational success in PBO's.

Figure 4: Levels of activties in PBO's; Organizational level (green) and project level (purple) (Created by J. Steinfurth, inspired by [19]

Application

The context of application

Before going into application strategies it is important to understand the context in which one applies the theory. The application of the PBO structure will vary depending on this "pureness" and the context of the organization, cf. the paragraph "Organizational context in the PBO". Furthermore, to be able to apply this organizational model, an organizational change is necessary, meaning one should be familiar with the good practices and theories of organizational change management. Transforming organizational structures is a big task that needs to be planned carefully, as it involves not only structures but people and the mindset of those.

Theories on change management is vast. This paragraph will present one change theory elaborating on it in the context of the PBO, based on the theory presented in the section "The big idea". It gives the reader an overview of the steps in a change process and can help to make a small test of the PBO structure, by applying it in small scale on one or two teams. For full application the reader is referred to the annotated bibliography, to further reading on organizational change, as there is a manifold of theories that could potentially be used for transitioning to a PBO form, depending on the organizational form one wants to transform from. The PBO specific considerations presented below will be adaptable to most change theories.

Application strategy to transform to a PBO

An existing and well known strategy of change is Lewin, K.'s three step model (1952). [21] Here it is presented with the expansion made by Lippet, R. et. al. 1958. [22]

The model divides change into 3 stages[21], with 3 subphases in step 2 [22]:

- Unfreezing status quo

- Moving to a new status

- Clarification of the problem

- Examining alternatives

- Defining and performing change initiatives

- Refreezing new status quo

1. & 2. Initially the change agent needs to realize that a change is needed and prepare for moving to a new status quo.

2.1 The change agent firstly need to understand the given problem and root cause for why the change is needed. When this stage has been fully investigated it is possible to start understanding if the PBO would be a fitting structure, by analysing if the problems fit with those that a PBO structure can help solve.

Based on the theory on PBO's one needs to consider the following questions, to understand if the PBO structure can help solve the problem.

- Are you doing or moving towards doing a project oriented business;

- Are projects becoming more important in your organization and can you see them becoming main drivers? If yes, is it beneficial that this is happening? In what way?

- Is lack of flexibility and authority of the project manager a root cause for project failures or organizational effectiveness challenges?

- Are the projects complex and uncertain and therefore need high flexibility to have a proactive approach (PBO) or are you rather handling projects with high predictability (eg. functional organization)?

- Are the projects often collaborating across other organizations and need to be able to quickly adapt to client/partner needs?

2.2 If these questions have all been answered with a yes, one needs to take a little step back again. These characteristics are namely similar to that of other organizational structures. This follows Lippet's 2nd subphase in the change model. Examining alternatives;

- Are there other organizational structures that fit better? e.g. the matrix organization has similar characteristics yet focus on the combination of the functional and project oriented work. The personnel refer to 2 bosses to keep equal importance on project and functional units. [23] Research other organizational structures that may better fit with your detailed and contextual answers to the questions above.

- Could the matrix form be more suited for the organization?

- How important is the functional parts vs. the project manager - who should be in charge?

- Do you need a pure PBO or rather a project led organization with weak links of functional management, where project manager still has the highest authority and is the main referee for employees?

2.3 The change agent has now analyzed if the PBO could potentially solve the root cause of the problem underlying the need for change. If the PBO is assessed as a possibly solution the next step is implementing the structure. The 8 step model, introduced by John Kutter and presented in the PMBOK guide is here utilized in a combination with the theory on adaptive approaches presented in the PMI portfolio guide.[24] [25]

- Create urgency; In the steps above one should have defined the problem. This will help create urgency, by defining the threats if not changing to a the PBO structure.

- Form a powerful coalition; Adaptive approaches needs a culture in which self management is highly valued. Identify the people in your organization that practice this already, and make them your co-change agents.

- Create a vision for change; Your vision should build on your initial analysis of the status quo. What values does a PBO bring; flexibility in projects, ease in cross organization collaborations etc.

- Communicate the vision; The change should be communicated throughout the entire organization; Why is it happening and what are the benefits?

- Remove obstacles; Adaptive approaches often need change in the way of working, reporting structures and mindset. In the adaptive approach i.e. PBO, reporting structures are important as these often become lost because of the high flexibility. Create the habit of reporting in a learning database from the beginning of the change. [26] [10]

- Create short term wins; Make a test with a small team and a smaller project. Remember to follow the characteristics of the PBO. Create a team that is free of the organizational structures, with a PM that has the flexibility and authority to make decisions.

- Build on the change; If the above experiment was a success then build on that with more teams.

- Anchor the changes in corporate culture; Acknowledge the people in your organization that are practicing self management and are adopting the new ways of working.

Performing the steps above would lead to an incremental change of the organization.

3. The last step would be a refreezing of the new status quo; The project based organizational structure. This entails sustaining the change. [21]

This concludes the application strategy that this article will present.

Limitations

Limitations inherent to the PBO

This article has shown how the PBO has many advantages, when working in dynamic and flexible environments, with high uncertainty and risk. However, in the pursiut of a flexible organizational structure the PBO also loses some of the advantages that the functional organization has. The lack of structure means that PBO’s often have a hard time sharing knowledge within the organisation and across the projects within it. [10] [3] Organizational learning instead often only happens within the projects and the temporary organizations they create. [9]. Sharing learnings across the organization is an important practice as it sets important values into play and helps realize benefits. Valuable benefits may be missed if these are not shared to other projects to adapt and integrate them. [10] Furthermore, if the PBO is integrated in a functional organization (or other organization with similar structures), the projects within the PBO often have difficulty in communicating with the static part of that organization. [10] This internal organizational communication problem, can also happen in the pure PBO, between the projects and the senior management (and additional entities that may be part of the static part of the PBO), thereby losing support and creating tensions within the organization. [2]

The PMI standards for Project, Program and Portfolio management, addresses some of the above mentioned limitations of the PBO. However these management practices and standards are often generic in how they address the organizational structures and theories. [18] The following will present how the standards address organizational learning and capability building and relate it to the PBO theory.

The PMBOK guide presents a short paragraph on knowledge management. It states how learnings can both be contextual and general, and that the general knowledge should be shared across the organization for utilization. [27] Furthermore, the guide explains that a project should be adapted to the given organizational contexts. It presents the organizational units Value Delivery Office (VDO) and the Project Management Office (PMO), whose roles amongst other include building capabilities throughout the organization and delivering value across portfolios and programs, respectively. The offices are often present in organizations that follow "adaptive delivery approaches" , which follows the PBO theory. [28] However, the standard lacks to present a practical guide on how the these initiatives of sharing knowledge can be integrated across an entire organization. A guide containing practical steps would be crucial in the PBO context, where the projects are weakly, if at all linked to each other. [2] This lack of development in the organizational domain is recognized by Michel Thiry, who challenges the way PMO's are implemented in practice. The article suggest that the PMO is merely a mimic of the functional organizational structures, put in a project management terminology. It suggest to integrate the structure of the PMO further into the PBO, adapting it to the project oriented approach, thus living up to the theoretical role of capability building as well as expanding the role to knowledge sharing and strategy linking activities. [4]

The PMI standard further addresses the PBO's limitations through a roadmap for integrating learnings and capabilities [29]. However, the roadmap is generic, and neither presents a step by step guide nor good practices. The same pattern is present in the portfolio management standard; it acknowledges that capability building is important and that it need to be adapted to the context of the organization, yet the practical steps still lack. Lastly, the PMI standard, presents one crucial practical initiative; a learning database. [26] Anna Mahura and Gustavo Birollo, present a manifold of researchers who study this formal knowledge sharing initiative, showing that it is in practice a valuable and applicable tool for formal knowledge sharing. [10] They also argue that formal knoweldge sharing needs to be combined with informal knowledge sharing across the projects within the organization to enable cross organizational learning. Summarizing, the PMI project, program, portfolio standards puts a focus on the problem of lack of knowledge sharing and capability building across the wider organization, as well as present the learning database practice and frameworks for integrating capabilities. However, in the context of the PBO where these limitations are distinct, the standards reach short in the practical approach.

Limitations in application

Transforming to a Project based organization in practice is as metnioned a huge task to take on. This is because it is not merely a tool, yet an entire restructuring of an organization or part of it. As explained in the paragraph "Application", the people in the organization need to go through large changes. Change management in itself is already a major management topic, that needs training, time and resources to practice. Furthermore, the theory of PBO's can be a difficult and complex field to understand, especially if not familiar with basic organizational theory. The theory expands across several domains; organizational theories, management, project management etc..[30] Additionally in PBO literature and research the definition and the terminology varies and has evolved over time and not all researchers define and explain the PBO in their work, as the definition is implicit in the work they do. [1] [3] [9] This can make it difficult to research if not known in the field. To show this great variance as well as the help the reader search for further information on the topic, and overview of some of the terms that can refer to the PBO or similar organizational forms is given [1] [3][9][31]:

- Project based organisations

- Project led organisations

- Project based enterprises

- Project based industry

- Project based firms

- Multiple project organisation

- Temporary organisations

- Projectized organizations

The different terms are often used in different contexts and highlight a specific field of study, eg. temporary organizations are often PBO's but refer to the study of the organizational structures whereas literature using the term project based organization is often in the crossing between the two fields of study; project management and organizational structures [1]. This shows how vast and complex it may be to gain the necessary knowledge for successfully transforming and organization to a PBO.

Lastly, transitioning to a project based organizational form is not only a large task because it needs understanding of both PBO theory as well as change management theories but also because organizational change management needs expertise and experience to practice properly. This means that depending on the level of expertise and experience of the change agent, a transition to a PBO may require a significant amount of resources.

Annotated bibliography

1) Davies, A., Hobday, M., 2005. The project-based organisation, in: The Business of Projects: Managing Innovation in Complex Products and Systems. Cambridge University Press, pp. 117–147. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511493294.007

This book is a great resource for understanding the core principles of project based organzations. The book is about projects and complex products and systems and suggests a form of PBO for the development of such complex and uncertain systems. In it you will find project management and organizational theories in general with a specific chapter dedicated to project based organizations. In that chapter is a case study comparing the PBO to a functional organization; definin some of the core values of Project Based Organisations in practice.

2) Kroon, J., 1995. General Management, Second. ed.

This book is presents management theory. Wihtin this article it has mainly been used to get an understanding of different organizational structures. The book has an entire chapter devoted to "organizing", in which it presents organizational types in detail, as well as displaying them through graphical tools; organizational charts.

3) Petro, Y., Gardiner, P., 2015. An investigation of the influence of organizational design on project portfolio success, effectiveness and business efficiency for project-based organizations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 33, 1717–1729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.08.004

This article investigates the PBO in relation to portfolio management. Is investigates how the structure and design of an organization can have influence on project management and vice versa, and discusses hypotheses on how the project oriented organizational structures can enhance portfolio success, due to the characteristics of high authority in PBO structures.

4) Thiry, M. (2007). Creating project-based organizations to deliver value. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2007—EMEA, Budapest, Hungary. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute

5) Söderlund, J., Hobbs, B., Ahola, T., 2014. Project-based and temporary organizing: Reconnecting and rediscovering. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 32, 1085–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.06.008

This article is relevant for further reading, if interested in the relations between project management and the PBO more specifically how sharing of project management practices between projects can happen in a PBO. In this discussion the article focuses on the terms of effectiveness and efficiency in a process project management domain, and suggest that these are relevant to define to help create standards for project management across a PBO.

In this article a further explanation of the role of the PMO in a project based organization can be found. The article is available through PMI's database, and presents several organizational governance models in the PBO context.

Change management theory

1) Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 4.2.4 Change Models. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZKN2/guide-project-management/change-models

This section in the PMBOK Guide gives an overview of different change management models, including Change in Organizations, ADKAR model, the 8-step process for leading change, Virginia Satir Change Model and Transition model. It is an easy way to get an impression of the change management models and if they could be relevant to research further.

2) Dawson, P. 2003. Organisational Change: A Processual Approach. London, UK: Chapman & Hall.

This reference is relevant in the PBO context as it challenges the refreezing stage presented in the theory. It argues that this stage is not reached in dynamic environment because changes happen continuously.

3)Beckhard, R., and R. Harris. 1987. Organizational Transitions: Managing Complex Change. 2nd ed. Reading, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley.

This change management book includes a different version of the three-stage model as well as other change management models amongst other the gap analysis and feedback mechanisms.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Bakker, R.M., 2010. Taking Stock of Temporary Organizational Forms: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 12, 466–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00281.x

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Davies, A., Hobday, M., 2005. The project-based organisation, in: The Business of Projects: Managing Innovation in Complex Products and Systems. Cambridge University Press, pp. 117–147. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511493294.007

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Thiry, M., Deguire, M., 2007. Recent developments in project-based organisations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 25, 649–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.02.001

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Thiry, M. (2007). Creating project-based organizations to deliver value. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2007—EMEA, Budapest, Hungary. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Hobday, M., 2000. The project-based organisation: An ideal form for managing complex products and systems? Res. Policy 29, 871–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(00)00110-4

- ↑ Pryke, S., 2017. Managing Networks in Project‐Based Organisations, Managing Networks in Project‐based Organisations. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Petro, Y., Gardiner, P., 2015. An investigation of the influence of organizational design on project portfolio success, effectiveness and business efficiency for project-based organizations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 33, 1717–1729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.08.004

- ↑ Turner, R., Miterev, M., 2019. The Organizational Design of the Project-Based Organization. Proj. Manag. J. 50, 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972819859746

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Leiringer, R., Zhang, S., 2021. Organisational capabilities and project organising research. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 39, 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2021.02.003

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Mahura, A., Birollo, G., 2021. Organizational practices that enable and disable knowledge transfer: The case of a public sector project-based organization. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 39, 270–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.12.002

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kroon, J., 1995. General Management, Second. ed.

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Portfolio Management (4th Edition) - 1.8 Relationships among Portfolio Management, Organizational Strategy, Strategic Business Execution, and Organizational Project Management. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0XW1/standard-portfolio-management/introducti-relationships

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Sydow, J., Lindkvist, L., & DeFillippi, R. (2004). Project-Based Organizations, Embeddedness and Repositories of Knowledge: Editorial. Organization Studies, 25(9), 1475–1489. https://doi-org.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/10.1177/0170840604048162

- ↑ Dosi, G., Nelson, R., & Winter, S. (2000). The nature and dynamics of organizational capabilities. Oxford: OUP

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 2.8.3.3 Process-Based. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZJ73/guide-project-management/process-based

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/toc/id:kpSPMAGPMP/guide-project-management/guide-project-management

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Sundqvist, E., Backlund, F., Chronéer, D., 2014. What is Project Efficiency and Effectiveness Procedia? - Soc. Behav. Sci. 119, 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.032

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Thiry, M. (2006). A paradoxism for project-based organizations. Paper presented at PMI® Research Conference: New Directions in Project Management, Montréal, Québec, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Portfolio Management (4th Edition) - 1.4 Relationships among Portfolios, Programs, Projects, and Operations. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0XS2/standard-portfolio-management/relationships-among-portfolios

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Program Management (4th Edition) - 1.5 The Relationships among Organizational Strategy, Program Management, and Operations Management. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0S2J/standard-program-management/relationships-among-organizational

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Lewin, K. 1952. Field Theory in Social Science - Selected Theoretical Papers. Edited by Dorwin Cartwright. London, UK: Tavistock Publications Ldt.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lippet, R., J. Watson, and B. Wesley. 1958. The Dynamics of Planned Change. New York , NY, USA: Harcourt Brace, Jovanovich

- ↑ Stuckenbruck, L. C. (1979). The Matrix Organization. Project Management Quarterly, 10(3), 21–33.

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 4.2.4.3 The 8-Step Process for Leading Change. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZKQ1/guide-project-management/8-step-process-leading

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 2.3.4.3 Organization. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZH42/guide-project-management/organization

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Program Management (4th Edition) - 8.2.4.1 Lessons Learned Database. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0VO1/standard-program-management/lessons-learned-database

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 2.5.8.2 Explicit and Tacit Knowledge. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZI11/guide-project-management/explicit-tacit-knowledge

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 3.4.2 Tailor for the Organization. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZJR1/guide-project-management/tailor-organization

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Program Management (4th Edition) - 3.3 Program Roadmap. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0SK8/standard-program-management/program-roadmap

- ↑ Söderlund, J., Hobbs, B., Ahola, T., 2014. Project-based and temporary organizing: Reconnecting and rediscovering. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 32, 1085–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.06.008

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Portfolio Management (4th Edition) - 5.5.2 Supply and Demand Allocations. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0ZO3/standard-portfolio-management/supply-demand-allocations