Negotiations

Created by Gudrun Karitas Blomsterberg

Summary

Negations are a part of everyday life, a useful skill in both personal and professional settings. Negotiations are highly relevant to project management, as they encourage alignment with key stakeholders, play a large part in resource allocation and organizational structures, and risk management. Being skilled at negotiating can prevent conflict in projects and enable smoother project execution. It is also useful in our personal lives as it can enable us to buy our dream home, help us launch our start-up, and even give us an advantage when deciding who must do the dishes. Therefore, it is safe to conclude that the art of negotiation is a skill useful and relevant to everyone. This article will provide a review of the relevance of negotiation for project managers and explore the key factors that determine the trajectory of negotiations, such as different personality types and power. Additionally, cultural differences and their impact on negotiations are examined, a relevant topic as negotiations between parties with different cultural backgrounds become more common. Finally, this article will address the benefits and limitations of the negotiation process.

Contents |

The Big Idea

Negotiations refer to discussions between two or more parties to reach an agreement. The different parties usually come to an agreement through a series of back-and-forth discussions, strategies, demands, and tactics [1]. Negotiation is a complex process involving multiple factors that contribute to the outcome of the process. Studies have been conducted on that very issue for the purpose of determining the key factors that significantly influence the success of the negotiation. But what are the determining factors when it comes to the outcome – is it personality traits, a specific tactic or negotiation approach, and is there something that will ensure success every time?

The Importance of Negotiations in Project Management

Being a skilled negotiator is beneficial for everyone and especially project managers. Most projects have contracts and/or procurement - procurement can mean physical materials or products, labour, and services. These things involve negotiating and a good project manager must be a skilled negotiator or hire one. It has great influence on the financial side of projects and is a skill that comes to great use for stakeholder relations and conflict management. Stakeholders play a large part in projects and can directly or indirectly influence the outcome of projects. Project teams are a group of stakeholders that communicates with other groups of stakeholders, they must take into consideration the interests, needs, and opinions of the other stakeholder groups. Stakeholders must be analyzed and engaged with from the start [2]. Conflicting interests must be addressed, addressing conflicts at a late stage often leads to disappointment and can be avoided and settled by negotiating [3].

Resource allocation, project budget, and timelines are often re-evaluated over the course of projects, where negotiations play a key part. Negotiations are not only a part of the first steps in projects but are repeated when needed over the project’s lifetime. Having a project manager who is a skilled negotiator can save a lot of money and time, as no outside council is needed.

The four perspectives of project management are purpose, people, complexity, and uncertainty. The most relevant to negotiations is people. For a team to perform at its best conflicts need to be addressed, as they are unavoidable[4] - so it does not come as a surprise that conflict resolution is a tool frequently used by project managers[2]. Conflicts emerge because of stakeholders’ different views, goals, and interests. Project managers need to develop their soft skills to interact with people, after all around 80% of their time is spent on communication[4], so it’s important to be able to actively listen, lead, establish a vision, prioritize, and negotiate[2].

Single and continuous negotiation

There is no one negotiation style or approach that suits every occasion. The approach during a single-time negotiation differs from a continuous negotiation process. During the single-time negotiation, the main goal is to maximize success in the least amount of time, and the main focus is on the outcome and on “winning the negotiation”. In the latter case, more emphasis is placed on the process, building trust, and encouraging an atmosphere of cooperation. Continuous negotiations are often the case between long-term partnerships, supplier-client, etc., where it is important to consider the consequences of every step as it influences the current negotiation, as well as future ones[5]. The key to a long-term partnership is a good foundation and a mutual relationship based on trust and cooperation[3].

Personalities

The impact of personalities, attitudes, and motivation on the outcome of a negation process is a topic of interest in research. Over 200 studies were reviewed to determine whether personal characteristics play a role in the negotiation process and its outcome. Although gender differences may affect negotiation strategies, no specific character traits were found to consistently link to successful negotiation. The studies that revealed a difference in gender regarding negotiation strategies found that women were not as likely to mirror an opponent’s concessions when bargaining with a passive counterpart, while others find no difference. High-risk takers were competitive and made fewer concessions than low-risk takers. A study examined the effects of 31 personality traits in an attempt to find out which ones affected negotiation the most and did not find a significant relationship between any of the traits and the outcome of negotiations but found that the negotiator preferences were linked to the bargaining outcomes[6].

Our behaviour influences the decisions and behaviour of the opposite side. Having high demands can lead to frequent deadlocks if it is combined with low concessions by the opponent. Threats and strong demands are often detrimental to productive bargaining, as they tend to result in retaliation. Recent work supports and clarifies this, showing that such behaviours are harmful unless they are seen as legitimate, subtle, or not used to gain an advantage over the opponent[1]. In negotiations, the concept of egocentrism, sometimes referred to as motivational bias, plays a significant role. This bias leads different parties to overweigh the objective that favours them, resulting in a subjective judgment of fairness. The degree of egocentrism displayed by the parties involved can directly impact their ability to reach an agreement. The more egocentric the parties are, the more challenging it becomes to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome[7].

Culture

Nowadays, doing business across different cultures is the reality of many organizations. Having distributors, suppliers, shareholders, and stakeholders from all over the world increases the complexity of decisions, operations, and tactics.[8]. There seems to be a significant difference in how different negotiation tactics are perceived in different cultures. Western society has an emphasis on efficiency and cost-effectiveness rather than developing a relationship with their opponents. In contrast, Eastern culture places value on building an interpersonal relationship with the other parties. The outcomes differ as well, western societies tend to focus on right and wrong, while Eastern cultures prioritize goodwill. Capitalistic countries focus more on justice and equity, while socialists place an emphasis on equality. If the parties negotiating come from the same culture, these norms will most likely influence the process but if they come from different cultural backgrounds the whole process tends to be more stressful and competitive[1].

People can be classified into three different groups based on their origin and culture, these groups are: linear active, multi-active, and reactive. The first group is task-oriented and highly organized, this group includes people from countries such as the United States, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK. These negotiators rely on data, well-defined processes, and a clear-cut understanding of every element in a system. Efficiency and practicality are major factors here and this group typically plans every step of the process methodically and focus on one issue at a time. The second group is people-oriented, and communication is at the core of who they are. People from this group come from Hispanic America, Africa, Russia, Italy, and Spain, to name a few. They are known for laying the outlines and focusing on the big picture instead of approaching the negotiation in a systematic way, as well as having a tendency of discussing multiple issues simultaneously. The last group is introverted and assumes the position of listeners who approach conversations and negotiations with a deep sense of respect. This culture group includes Vietnam, China, Japan, Korea, and Singapore. They place importance on harmony in communication, as well as abating to power hierarchies. Gathering small details to then later piece them together to make up the large picture is something that this group does before making their decisions[9].

But it is not enough just to be aware of these cultural differences. It is important to consider that even though culture plays a large part in how a person perceives the world, the assumptions above are merely a framework based on stereotypes, and people are more multidimensional than that. Respecting other cultures and being aware of how the opponent perceives one's own culture, and how the opponent might take a different approach based on that is important to consider[10].

Power

In negotiations different types of power are at play, there are three main categories. The first one has to do with having a strong BATNA. BATNA, or the best alternative to a negotiated agreement, as it can protect against accepting an offer way below what is available, just to avoid not reaching an agreement. Being aware of other options and ways of getting what is needed, can confer power, and reduce the desperation to reach an agreement[11]. The second source of power is from a particular position within an organization, often referred to as role power. The third and last category is psychological power. Believing that one is powerful often leads to the same consequence them having actual power[12].

But having power in negotiations is not just a positive thing. It has been linked to people losing sight of the opponent’s vantage point and overlooking their needs and the reasons for those needs. Some of the benefits of feeling powerful when negotiating is that it leads to more risk-taking and more creative solutions. It can decrease the feeling of being trapped within the opponent’s constraints and focus on the potential payoffs instead of the potential dangers[13].

Application

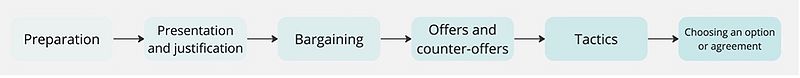

The negotiation process is demonstrated in Figure 1. Each step is important, during preparation one should gather the facts available and make a strong BATNA and collect information about the opponent, their culture and stereotypical behavioural patterns, and how they could possibly perceive one’s own culture. During the next steps of the process, being aware of one’s demands and how they are perceived is important, because they can affect the opponent’s behaviour [14].

Cultural differences can create be difficult to navigate but they are also an opportunity to learn. Researching the other side’s culture by reading and having conversations with others who know the culture can be beneficial, and the other side will most likely appreciate the interest. Seeking to understand and always showing respect for the differences will create a cooperative environment and enable the negotiation process to run more smoothly[10].

The goal of negotiations should be to ensure that both parties achieve favourable outcomes, not to win at all costs. In the paper “Negotiating for success: are you prepared”, which was presented at PMI Global Congress in 2010, the author who is an experienced negotiator explains how they navigated the process, which included different personalities, various negotiation styles and approaches. They emphasized the importance of being prepared and the power of simply and fearlessly asking for what one wants, as it can obtain significantly better results and create an environment of honesty. It is also important to define success in terms of the project or negotiation before the process is initiated[15].

Good negotiation involves trying to find the third alternative and looking beyond the traditional win/lose outcomes. Humans tend to view situations in a very “clean-cut” way, and in terms of wins/losses. This binary perspective leads to an approach where winning or losing are the only options. However, it is crucial to recognize that there is often a third option available. Identifying this third option may require more effort and time, but it might lead to a win-win situation[15]. This alternative can foster synergy and maximize the potential for a mutually beneficial outcome and encourage a collaborative atmosphere leading to higher benefits for both parties[9].

According to Steven Covey’s model for negotiations, there are three possible outcomes: win-win, win-lose/lose-win and finally lose-lose. He suggests that to cultivate an environment where the outcome is win-win both parties must have a mature look on the process and believe that there are enough resources for everybody. Trust plays a key role, both parties must trust each other and both parties must have the ability to look at the situation from the other’s perspective. For this win-win outcome to become a reality, both parties must work together[2].

Successful negotiations require a patient and positive mindset and the gathering of relevant information. This information may include deadlines, alternative solutions, information about the decision-making authority, motivations, and past negotiation tactics. When proposing a different direction, asking “what if” questions can be helpful as it sounds less like a commitment. It’s also crucial to understand the power dynamics at play and one’s status in the negotiations. Project managers may have significant decision-making authority, but when they take the role of a purchaser, the opponent or the seller has the superior bargaining position. Knowing your opening offer and not revealing your bottom line provides leverage for negotiation[15].

Directly dealing with the decision-maker usually leads to a quicker negotiation process. Preparation is key to avoiding surprises and making decisions based on emotion instead of facts. A risk management plan can help manage potential challenges. Finally, never reward intimidation tactics and be prepared to make concessions when the other party does, as it shows a sign of collaboration[15].

Benefits

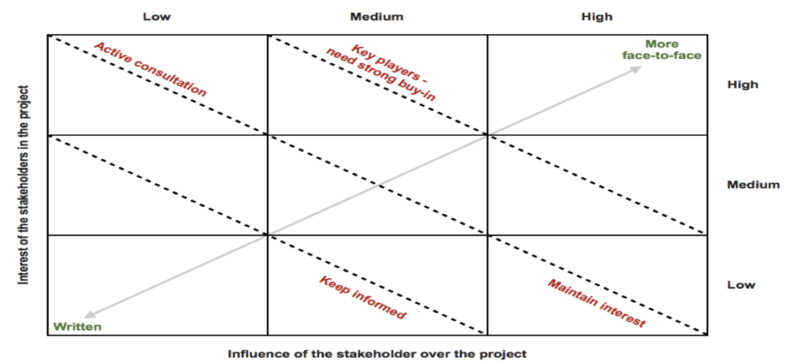

The benefits of negotiations for a project manager are numerous. Managing the different interests, motivations and priorities of stakeholders is crucial, as mentioned above. The job of a project manager is to be aware of these needs while working towards the project‘s final outcome and objective. Through negotiations, stakeholders‘ needs and points of view become apparent and a successful negotiation can lead to mutually beneficial solutions for all involved. A common tool in stakeholder management is stakeholder mapping, illustrated in Figure 2, engaging all groups and being especially aware of the group that has a high interest in the project and low influence, can encourage a collaborative and innovative decision-making process through negotiations. Negotiation can be used as a platform for everyone to share their views and feel heard[16].

Limitations

While theories offer clear guidelines on the dos and don’ts of negotiation, it is important to keep in mind that communication styles, body language and tone significantly impact how these strategies are perceived and play a large role in the outcome. Emotions are an inherent part of human decision-making despite the emphasis on leaving emotion out during negotiations. Some of the advice on negotiating is based on personal traits and is hard to mimic, and thus should not be adopted by everyone. Such as using humour, humour is of course something that everyone can use to lighten the mood, but the reality is that not everyone is funny or can use it to gain trust and build a relationship with others. Not authentically being yourself can have consequences that are contrary to the desired effect. Many of the elements that seem to be a large factor in negotiations relate to understanding communication and being emotionally mature[15].

The use of tools when negotiating can be effective in providing a framework throughout the negotiation process, but it is important not to rely too heavily on them, as it can lead to a rigid and inflexible approach - it is important to consider the uniqueness of each situation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, negotiations are an essential part of project management, it is a skill that can have great influence on the financial side of projects and on stakeholder management. Engaging stakeholders for the start can lead to fewer conflicts in the latter stages of the project‘s process and can be used to address conflicts to avoid disappointment later.

There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that there are certain personality traits that ensure the success of projects, but respect and understanding go a long way. Respect is especially important when dealing with people from different cultural backgrounds. Depending on people's origin and culture, they can be classified into three groups, linear active, multi-active, and reactive. There are certain traits that are frequent in each group but it is important to consider that people are multi-dimensional and that the studies that have been conducted are based on stereotypes.

A successful negotiation entails a favourable outcome for most parties involved, and during the negotiation process, it is recommended to try to look for a win-win situation.

It may not come as a surprise that there is not one tactic, approach or certain personality trait that can ensure success every time because each situation has different demands. There are many interesting studies on the topic and books have been written about how to enhance one‘s negotiation skills. The great thing about negotiation is that there is always more to learn and everyone can learn from their negotiations, reflect and try to do better next time – after all it is a skill that not only is very relevant in professional settings but also in personal ones.

Annotated Bibliography

- Englund, R. L. (2010). Negotiating for success: are you prepared? Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—EMEA, Milan, Italy.

- - The article provides great recommendations from an experienced negotiator. It is written with a project manager in mind and emphasises the importance of project managers being skilled negotiators. It is a great framework and is written structurally, and provides a good overview of the negotiation process. The author provides concrete advice like the ten rules of negotiating. The author does speak from experience but bases their recommendations on literature like A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide®).

- Ilyas, M. A. B. & Hassan, M. K. (2015). Negotiate to win across cultures. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2015—EMEA, London, England.”

- - In this paper, the author discusses negotiations across cultures, how they affect the negotiation process and how culture shapes perceptions. It roughly classifies people into three groups, which are then described. The author discusses different aspects of negotiation, like strategy and tools and provides useful tips. Many projects involve people with different backgrounds and this article is helpful as a guide on how to navigate the process.

- The standard for project management. (2021). A Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge (pmbok® Guide) – Seventh Edition

- - This book provides an overview of the best practices and standards in project management and is considered one of the main references in the field. The book places importance on stakeholders, which are an essential part of projects - it also covers risk management and communication which are relevant to negotiation. The book is a great tool for project managers and can provide them with a strong foundation in project management.

- Wall Jr, J. A., & Blum, M. W. (1991). Negotiations. Journal of Management, 17(2), 273-303.

- - The authors provide recommendations for managers to improve their negotiation skills. The effects of characteristics on negotiations are reviewed with an emphasis on the bargaining phase of the process. High-risk takers prefer a more competitive approach and found that gender did play a role but did not find a specific personal trait played a significant role. The authors review the effects of verbal behaviour and found threats to be detrimental. The article discusses the interactions between opponents.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wall Jr, J. A., & Blum, M. W. (1991). Negotiations. Journal of Management, 17(2), 273-303.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 The standard for project management. (2021). A Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge (pmbok® Guide) – Seventh Edition and the Standard for Project Management (english) (pp. xxvi, 67, 274 Seiten (unknown). Project Management Institute, Inc

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Züst, R. (2006). No More Muddling Through, No More Muddling Through : Mastering Complex Projects in Engineering and Management. No More Muddling Through. Springer Netherlands.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Thuesen, Christian. (2023). People [PowerPoint slides]. 42433 Advanced Project, Program, and Portfolio Management, Technical University of Denmark - DTU, Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Zohar, I. (2015). “The art of negotiation” leadership skills required for negotiation in time of crisis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 540-548.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, L., Neslin, S. A., & Gilkey, R. W. (1985). The Effects of Negotiator Preferences, Situational Power, and Negotiator Personality on Outcomes of Business Negotiations. The Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 9–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/256058

- ↑ Bazerman, M. H., Curhan, J. R., Moore, D. A., & Valley, K. L. (2000). Negotiation. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 279–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.279.

- ↑ DRAKE, L. E. (1995). NEGOTIATION STYLES IN INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION. International Journal of Conflict Management, 6(1), 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022756

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ilyas, M. A. B. & Hassan, M. K. (2015). Negotiate to win across cultures. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2015—EMEA, London, England. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Odeneal, Gail. (n.d.). Overcoming cultural barriers in negotiation. Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Retrieved 15.04.2023, from https://www.pon.harvard.edu/freemium/new-free-report-overcoming-cultural-barriers-in-negotiation/.

- ↑ What is a BATNA?. (n.d.). Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Retrieved 02.04.2023, from https://www.pon.harvard.edu/tag/batna/

- ↑ PON Staff. (11.04.2023). 3 Types of Power in Negotiation. Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Retrieved 15.04.2023, from https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/negotiation-skills-daily/types-of-power-in-negotiation/

- ↑ PON Staff. (04.04.2023). Power in Negotiation: The Impact on Negotiators and the Negotiation Process. Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Retrieved 15.04.2023, from https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/negotiation-skills-daily/how-power-affects-negotiators/

- ↑ Shonk, Katie. (23.03.2023). What is Negotiation?. Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Retrieved 15.04.2023, from https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/negotiation-skills-daily/what-is-negotiation/

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Englund, R. L. (2010). Negotiating for success: are you prepared? Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—EMEA, Milan, Italy. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ Yang, H., & Liang, P. (2013). Reasoning about stakeholder groups for requirements negotiation based on power relationships. Proceedings - Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference, Apsec, 1, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1109/APSEC.2013.42