Effort-Reward-Imbalance

Contents |

Abstract

In 1986, Johannes Siegrist, a medical sociologist and university professor, designed the Effort-Reward-Imbalance Model to predict and explain the effects of high effort with low return on the health of the heart [1]. This model has been further developed over the years and is used today to understand the effects of work on the health of the employee, in order to ideally prevent diseases. The model is designed to assess negative effects and stressful experiences at work and predict probabilities of illness. This imbalance can lead to a range of health problems such as stress, burnout, and depression [2]. Three primary hypotheses can be derived from the ERI model. First, the external ERI hypothesis, which states that high effort combined with low reward increases the risk of poor health. Second, the internal overload hypothesis can be derived from the model. The core message of this hypothesis is that a high, critical level of overcommitment also increases the risk of deteriorating health. These two hypotheses are ideally rounded out with the interaction hypothesis, which suggests that it is primarily the combination of too much effort combined with low reward and the assumption of too much obligation in the form of overcommitment that leads to an even higher risk of stress reactions [3]. The topic is becoming increasingly relevant in the field of employee leadership and project management. Project managers and general managers must become aware of the dangers of the imbalance of effort and return in order to generate possible implications for their work and leadership.

This article reviews the structure and idea of the model, the hypotheses, the methodology, the impact on health, possible limitations, project management implications and annotated bibliography.

Structure and idea of the model

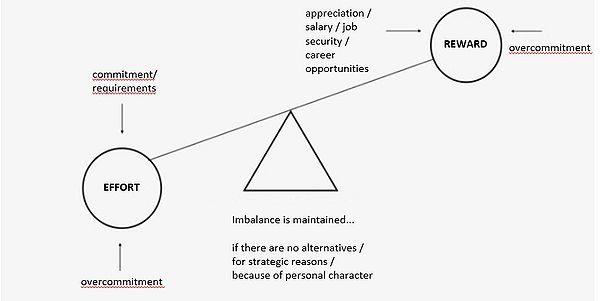

The goal of the model is to combine sociological information describing the work environment or setting, psychological information describing relevant person characteristics, and biological information describing immediate or long-term health outcomes. The model addresses the challenge of answering the question of what critical components of work life influence human health [2]. It is composed of three components, "effort," "reward," and "overcommitment," although "Overcommitment" was first added to the model in 1999 (see figure 1).

The effort is described in the model as the employee's obligation to the employer [1]. The concept of high effort can be divided into high extrinsic effort and high intrinsic effort. Extrinsic effort is the caused stress from outside, for example, in the form of work pressure or the general demands of the job. The high intrinsic effort defines above all the need for control, or the own motivation in a demanding work situation. Reward is described in the Effort-Reward-Imbalance model as professional reward in the form of money, appreciation and state control. In the model, the concept of state control, i.e., control over one's own occupational own professional status, is highly relevant. This includes the availability of advancement opportunities and job security. The combination of these two conditions of low reward coupled with high effort can have negative effects on various areas of job satisfaction, but especially on health.

Hypotheses

Three primary hypotheses can be derived from the ERI model. First, the external ERI hypothesis, which states that high effort combined with low reward increases the risk of poor health. Second, the internal overload hypothesis can be derived from the model. The core message of this hypothesis is that a high, critical level of overcommitment also increases the risk of a deteriorating health state. These two hypotheses are ideally rounded out with the interaction hypothesis, which suggests that it is primarily the combination of too much effort combined with low reward and the assumption of too much obligation in the form of overcommitment that leads to an even higher risk of stress reactions [3].

Methodology used in project management

Since 1996, the Effort-Reward-Imbalance-Questionnaire has typically been used to determine the imbalance between effort and reward. In practice, this questionnaire is also used in the context of general management activities and project management tasks to determine the stress level of team members in a project [1]. The questionnaire designed by Siegrist measures extrinsic effort, reward, and overcommitment, the three components of the ERI model. Extrinsic effort is measured using a scale consisting of six items related to the demanding aspects of the work environment [4]. For example, project members are asked if the worker is under constant time pressure due to a heavy workload. If the participant answers in the affirmative, the participant is then asked to rate the severity of this situation on a Likert scale. By asking questions of this type, it is possible for the project manager to better manage the workload of his or her employees [5]. Other items measuring extrinsic effort include physical workload, potential interruptions, level of responsibility, number of overtime hours, and increasing demand. The Reward Scale consists of 12 items that include two subscales, appreciation and status control.

The esteem scale contains five items, for example, the subjectively perceived respect that employees receive from their colleagues and managers. Status control is measured with six items, including the item of opportunity for promotion [5]). The operationalization of overcommitment has changed repeatedly over the years. The most modern versions of the questionnaire contain 5 items designed to measure the employee's ability to switch off from work after a day's work. The ability to switch off from work was declared to be the most important item [6]. Another item measures the participant's irritability.

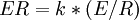

For each item, a minimum score of 1 and a maximum score of 4 must be achieved. To identify Effort-Reward Imbalance, the ratio is calculated as follows: with

with  for Effort,

for Effort,  for Reward, and

for Reward, and  as a corrective variable with

as a corrective variable with  . An imbalance exists if

. An imbalance exists if  is not equal to 1. When the value of

is not equal to 1. When the value of  is less than -1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of reward and when

is less than -1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of reward and when  is greater than 1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of effort [4].

As a project manager, its common to use these results to rethink one's behavior toward team members in a project in terms of whether to increase reward or decrease effort.

is greater than 1, it indicates an imbalance in favor of effort [4].

As a project manager, its common to use these results to rethink one's behavior toward team members in a project in terms of whether to increase reward or decrease effort.

Impact on health

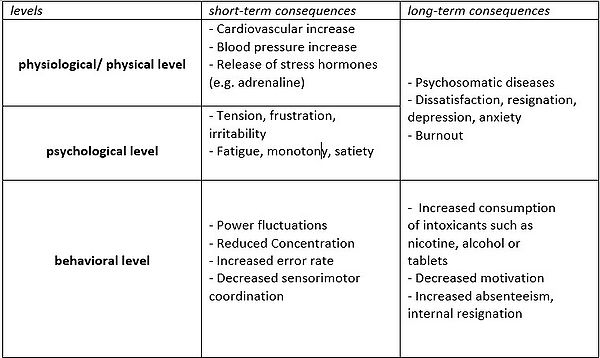

Health effects can be divided into physiological, mental, physical, and behavioral. A meta-analysis by Faragher et al. from 2005 provides a systematic review from 485 studies with a total size of 267,995 study participants on job satisfaction and consequences on health. The calculation yields a combined overall correlation of job satisfaction and health of r=0.370. Accordingly, a valid positive correlation exists [7]. The model describes that health consequences can arise from persistent stress reactions. Factors that have a high probability of triggering a stress response are called stressors and play an important role in the relationship of the ERI model and the health of the worker [8]. The consequences of stress reactions and stress differ on the temporal and content levels. On the one hand, short-term consequences exist, such as fatigue, monotony, or satiety, however, on the other hand, there are numerous possible medium- to long-term consequences, such as depression. On the content level, the consequences of stress on health differ between the physiological, psychological, physical and behavioral levels (see figure 2, [9]). As a project manager, it is useful to be aware of the impact of effort-reward imbalance on health in order to generate implications for your own work and people management.

Psychological/psychosomatic health effects

An imbalance of effort and reward can have negative influences on the psychological well-being of the individual. An example of this is a study in the Japanese nursing system from 2017, in which 17.9% of the 173 study participants stated that they suffered from high psychological stress. The Effort-Reward-Imbalance-Questionnaire was used as the survey baseline in the study [10]. Two of the most common psychological stress disorders are burnout and depression. These psychological and psychosomatic health consequences are also relevant for project managers, as a possible long absence of the affected employee should be prevented.

Depression

The number of people currently suffering from depression is high.

The German Depression Aid Foundation has determined that 11.3% of women and 5.1% of men in Germany suffer from depression. In terms of their severity, depression is one of the most underestimated diseases [11].

2015, more people died by suicide (10,080) caused by depression in Germany than by drugs (1,226), traffic accidents (3,578), and HIV (371) combined [12]. Depression is expressed in the form of impaired mood, as feelings of dejection, anxiety, loss of pleasure, emotional emptiness, lack of drive, loss of interest, and numerous physical complaints [13]. Faragher et al's meta-analysis of 485 studies and 267,995 study participants calculated the correlation of job satisfaction and depression.

The correlation is positive and is  . Accordingly, there is a positive relationship between job satisfaction and depression. The meta-analysis makes it clear that employees who are subjectively lower in the hierarchy of the company are more likely to suffer.

If the work does not provide adequate personal satisfaction, or even causes dissatisfaction, this can develop into persistent psychological stress over a longer period of time. The associated lower self-esteem increases the chance of suffering from mild depression or

anxiety. If this condition remains unresolved over an extended period of time, it can lead to emotional exhaustion, which can result in an increase in depression. In studies prior to 1980, the averaged correlation of job satisfaction and depression was

. Accordingly, there is a positive relationship between job satisfaction and depression. The meta-analysis makes it clear that employees who are subjectively lower in the hierarchy of the company are more likely to suffer.

If the work does not provide adequate personal satisfaction, or even causes dissatisfaction, this can develop into persistent psychological stress over a longer period of time. The associated lower self-esteem increases the chance of suffering from mild depression or

anxiety. If this condition remains unresolved over an extended period of time, it can lead to emotional exhaustion, which can result in an increase in depression. In studies prior to 1980, the averaged correlation of job satisfaction and depression was  . This was followed by a slight increase to

. This was followed by a slight increase to  by 1990, but since 1990 the value has dropped to

by 1990, but since 1990 the value has dropped to  [7]. Workers with increased overcommitment have a 1.92-5.92-fold chance of experiencing psychosomatic symptoms such as depression compared to workers with low levels of commitment. The data reported by Van Vegchel et al. reviewed mostly only examined the relationship between Effort- Reward imbalance and overall psychosomatic health. Most of these studies found a positive correlation between ERI and psychosomatic outcomes. Workers who work in a high-effort-low-reward situation have an increased chance of 1.44-18.55% psychosomatic outcomes, such as depression [1]. An analysis of existing studies conducted by Johannes Siegrist

2006 conducted an analysis of existing studies supports the results collected so far. The combination of high effort and low reward increases the probability of a depressive disorder by 50 to 150%. The results are more consistent for men. Siegrist also confirms Faragher et al.'s hypothesis that the effects are more pronounced in groups with low occupational status [14].

[7]. Workers with increased overcommitment have a 1.92-5.92-fold chance of experiencing psychosomatic symptoms such as depression compared to workers with low levels of commitment. The data reported by Van Vegchel et al. reviewed mostly only examined the relationship between Effort- Reward imbalance and overall psychosomatic health. Most of these studies found a positive correlation between ERI and psychosomatic outcomes. Workers who work in a high-effort-low-reward situation have an increased chance of 1.44-18.55% psychosomatic outcomes, such as depression [1]. An analysis of existing studies conducted by Johannes Siegrist

2006 conducted an analysis of existing studies supports the results collected so far. The combination of high effort and low reward increases the probability of a depressive disorder by 50 to 150%. The results are more consistent for men. Siegrist also confirms Faragher et al.'s hypothesis that the effects are more pronounced in groups with low occupational status [14].

Burnout

The number of burnout cases has increased by 700 percent in the last 15 years [11]). Burnout is expressed as a feeling of exhaustion and lack of energy. The sufferer builds up a mental distance to his work and associates negativity with his workplace. Job efficiency declines rapidly [15]. Faragher et al. found a correlation of  between job satisfaction and burnout for this effect of poor effort to reward ratio. This is the highest score of correlation between job satisfaction and consequences found in this study. The correlation was

between job satisfaction and burnout for this effect of poor effort to reward ratio. This is the highest score of correlation between job satisfaction and consequences found in this study. The correlation was  between 1980 and 1989 and

between 1980 and 1989 and  from 1990 onwards. Consequently, a decrease in correlation can be observed [7]. All of the studies conducted by Van Vegchel et al. confirmed that when there is an imbalance of effort and reward there is an increased risk of emotional exhaustion. The influence of overcommitment was examined by some studies, but no significant influence could be confirmed. A study by Bakker et al. only examined the relationship of over-commitment of nurses to the risk of the disease [16]. Other studies [17] could not confirm this effect. The influence of over-commitment cannot be applied to the population [1].

The study by Bakker et al. is nevertheless a a good example to understand the influence of an imbalance of effort and reward on a Burnout diagnosis to be understood. The sample consisted of 204 nurses in Germany. Those who experienced an imbalance between effort and reward experienced increased levels of emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, interaction effects became apparent, indicating that emotional exhaustion combined with decreased personal accomplishment was particularly prevalent among the

nurses who experienced effort-reward imbalance [16].

from 1990 onwards. Consequently, a decrease in correlation can be observed [7]. All of the studies conducted by Van Vegchel et al. confirmed that when there is an imbalance of effort and reward there is an increased risk of emotional exhaustion. The influence of overcommitment was examined by some studies, but no significant influence could be confirmed. A study by Bakker et al. only examined the relationship of over-commitment of nurses to the risk of the disease [16]. Other studies [17] could not confirm this effect. The influence of over-commitment cannot be applied to the population [1].

The study by Bakker et al. is nevertheless a a good example to understand the influence of an imbalance of effort and reward on a Burnout diagnosis to be understood. The sample consisted of 204 nurses in Germany. Those who experienced an imbalance between effort and reward experienced increased levels of emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, interaction effects became apparent, indicating that emotional exhaustion combined with decreased personal accomplishment was particularly prevalent among the

nurses who experienced effort-reward imbalance [16].

Physical health effects

Effort-reward imbalance results in physical problems in addition to the psychological and psychosomatic problems addressed. Physical problems related to the model can be divided into cardiovascular diseases, muscular problems, or the general restriction of the musculoskeletal system. There is a low but present correlation of  between ERI and cardiovascular diseases and also a low but present correlation of

between ERI and cardiovascular diseases and also a low but present correlation of  between job satisfaction and muscular problems [7].

between job satisfaction and muscular problems [7].

Cardiovascular diseases

The Effort-Reward-Imbalance model was originally designed to predict and explain the effects of stress at work on the heart and blood vessels [18]. An analysis of data from more than 600,000 men and women from 26 studies has confirmed the association between work-related stress and cardiovascular disease, such as stroke. Those who work more than 48 hours a week have a significantly increased risk. The risk of cardiovascular disease is increased by a factor of 1.34 on average for workers who are under stress. Furthermore, work-related stress can lead to a change in lifestyle over time and can lead to obesity. This has an indirect effect on cardiovascular disease [19]. Of the 45 studies reviewed by Van Vegchel et al, 17 examined and confirmed cardiovascular disease symptoms such as hypertension and an increase in cholesterol levels. The risk of diseases is higher by a factor of nine in employees who work with an imbalance of effort and reward [1]. It was found that the risk for women is increased mainly by over-commitment, and for men by effort-reward imbalance [20]. Since 1989, the correlation between job satisfaction and cardiovascular disease has nearly tripled from  to

to  [7]. The Whitehall II study by Kuper et al, confirms the above observations. Workers who experienced an imbalance of effort and return had an increased risk of coronary heart disease by a factor of 1.65. The British Whitehall study also found an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, another risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, this fact was only observed in the male participants of the study [21]. Overall, it can be concluded from this summary of studies that over-commitment and a poor work/outcome ratio can have life-threatening consequences. As a project manager, it's essential to acknowledge this fact and modify your expectations of the project team accordingly.

[7]. The Whitehall II study by Kuper et al, confirms the above observations. Workers who experienced an imbalance of effort and return had an increased risk of coronary heart disease by a factor of 1.65. The British Whitehall study also found an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, another risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, this fact was only observed in the male participants of the study [21]. Overall, it can be concluded from this summary of studies that over-commitment and a poor work/outcome ratio can have life-threatening consequences. As a project manager, it's essential to acknowledge this fact and modify your expectations of the project team accordingly.

Muscular problems/limitations of the musculoskeletal system

Work-related musculoskeletal limitations are a widespread health problem. They account for 61% of all work-related disorders. A 2014 literature review by Koch et al. examined 19 studies on the effects of effort-reward imbalance on the human musculoskeletal system. The influence of the external ERI hypothesis was found to be moderate, as 13 of the 19 studies recognized a significant correlation was recognized. Just 4 studies confirmed the influence of the overcommitment hypothesis on the limitation of the musculoskeletal system. Accordingly, there is no application to the whole population. 5 of the 19 studies examined the interaction hypothesis, of which only one study was able to establish a correlation. Accordingly, only the ERI hypothesis can be classified as significant [22]. A 2014 study of 199 childcare workers in Hamburg, Germany, was able to confirm the association between Effort-Reward Imbalance and physical problems. The risk of suffering muscular problems or experiencing physical stress is increased by a factor of 4 when the effort-reward balance is poor. Especially the lower back and the neck are risk areas of the body [23]. The overall correlation between job satisfaction and physical problems is  . However, the correlation between job satisfaction and muscular problems is considered low at

. However, the correlation between job satisfaction and muscular problems is considered low at  [7].

[7].

Effects on behavior

The impact of the model on individual behavior can be reduced to two primary observations. First, studies have found that there is a positive correlation between stress at work and increased smoking. To this end, in a study with study participants from a socioeconomically and occupationally homogeneous group consisting of 163 employees of a large industrial company, the relationship between psychosocial work stress and cigarette smoking was analyzed. The probability of belonging to the group of regular smokers in the presence of a poor work effort-reward ratio is more than four times as high (4.34) as in the absence of this imbalance [24]. Prolonged stress leads to dysfunction of the mesolimbic dopamine system, which stimulates addictive behavior. In another cross-sectional study in the metalworking industry, the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and increased alcohol consumption was confirmed. The desire to relax and switch off from everyday life is also of great relevance, as both points are addressed in the Effort-Reward-Questionnaire [1].

Further health consequences

Another effect of Effort-Reward Imbalance is hypertension. Hypertension leads to an absence of disease, which means that the body works in survival mode in stressful situations, preventing infections. Once this work-related stress situation is overcome, this protective mechanism of the body is abruptly shut down and the retained infections break out in a worse form [20]. Furthermore, in the meta-analysis by Faragher et al. correlations of  and

and  were found for the association of job satisfaction with employee self-esteem and anxiety [7].

were found for the association of job satisfaction with employee self-esteem and anxiety [7].

Projectmanagement implications

Project managers can use the ERI model as a useful guide. The model can help design and manage projects in a way that promotes employee well-being and productivity.

Possible implications for project managers include:

- rewards As a project manager, ensure that the rewards of the project are clearly defined. Each project member needs to know what they are working towards and what they will receive in return for their efforts and effort in contrast. This includes monetary rewards such as salary and benefits but also intangible rewards such as recognition and opportunities for growth, advancement and development.

- transparency Be clearly defined and transparent about the effort of the project being worked on. Project participants must have a clear understanding of the effort and results expected for the project. Realistic goals, milestones, and deadlines must be set and the appropriate resources and support needed to achieve them must be provided. By doing these two things, the effort and reward of the project will be calculable for each project member.

- workload The project manager must ensure that the workload is feasible. Overloading the staff will result in an imbalance of effort and return and may lead to the health consequences described. Accordingly, the workload must be appropriate and distributed among enough project members. It is important to select the right number of project members to make this goal feasible.

- engagement As a project manager, it is important to involve and engage the project members in the project. If all members feel that they are responsible for their work and can control it themselves, the personal reward in the form of feelings of happiness when the project is successful is also increased. This leads to a more positive relationship between effort and return. It is important to encourage project members to participate in decision-making and problem-solving processes and to give them the opportunity for feedback and suggestions.

- development The project manager should always make the project members feel that they have the opportunity to develop, grow and strengthen their skills through the project. Employees who feel that they are growing in their role are more likely to be satisfied have a better effort to reward ratio. The project manager should also provide training and development opportunities.

- job satisfaction In project management, job satisfaction is closely linked to project success as well as factors such as team dynamics, communication and leadership. When team members are satisfied with their work, they are more likely to be motivated and productive. Therefore, project managers must prioritize creating a positive work environment that promotes job satisfaction.

- team cohesion The ERI model also suggests that social support and team cohesion can reduce the negative effects of effort-reward imbalance. In project management, team cohesion is critical to success because it fosters communication, collaboration, and a sense of common purpose. Project managers must prioritize building strong relationships among team members and fostering a supportive team culture. Joint activities as a project team can be helpful in increasing the sense of community [25] [2] [18]

Overall, it is really important that companies and project managers recognize that a balanced relationship between effort and reward has a high significance for the health of the employee but also in the medium and long term on the company. Financial interests should not take precedence over employee health. This requires a reordering of priorities. Of course, profit maximization must continue to be an important goal of a healthy company, but this should not be at the expense of employee health. Companies and project managers should use strategies to manage stress and improve the work climate to ensure a good working environment in the long term. Large companies should be able to offer additional psychological support, especially for employees with diagnosed mental health problems. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that adjusting the selection process for hiring employees can prevent imbalance. The requirements that are placed on the applicant during the hiring process should be clearly defined. There should be no deviation from these clearly defined mental and physical requirements unless necessary. Adjustment to the requirements should still be possible on the part of the employer and the project manager, but only with simultaneous adjustment of the reward to maintain the balance between effort and reward. Maintaining the balance is also of great interest to companies, as it avoids unwanted terminations.

There are a number of measures that can be taken to ensure that people with mental illness receive early treatment in line with formal treatment guidelines and reduce the risk of relapse. These include factual information for all employees, confidence in action on the part of project managers through training (including role plays on how to talk to an employee who may be suffering from mental health problems), an open and non-stigmatizing corporate culture, and reintegration measures. Costs due to presenteeism and absenteeism can be avoided by creating a faster path to professional treatment. In addition, project managers should always take the initiative whenever possible. The affected employee should be approached if they feel they have become unfit for work. There should be no fear of contact. Concerns about the employee's well-being should be communicated and observations addressed directly. It should be imperative to offer to support the employee in any further steps [11]

Limitations

First of all, the model lacks to take into account differences in how employees perceive effort and reward. Some employees, for example, may be pleased with smaller rewards, while others may consider the same rewards inadequate. Furthermore, the model may not effectively capture the intricate interplay of multiple workplace stressors, such as role ambiguity or disagreements with coworkers. A precise socio-demographic and work-related analysis of the effects on health, would have ideally rounded off the evaluation of the empirical research. From the studies examined, it became apparent that there are differences in the severity of the burden between occupational groups. For example, a worker in nursing is exposed to different emotional stresses than a worker in finance. Furthermore, the evaluation of smoking behavior should be viewed critically, as the source cited there completed its research 30 years ago and this behavioral observation may have changed in the meantime. Unfortunately, more current sources could not be found. In the meantime, the fact that smoking has been banned in many professions may have reduced the number of regular smokers. In addition, the effects of Effort-Reward-Imbalance on behavior should be urgently re-examined in the future, as the type of drugs might have changed as well. Furthermore, the ERI model may not be appropriate to all job kinds and work environments. Some research has suggested that the model may be more relevant to high-stress, high-demand jobs than to low-stress, low-demand jobs. Finaly, because the model is primarily concerned with individual-level concerns, it may fail to adequately account for broader societal and organizational elements that contribute to job stress. Job instability, economic downturns, and company culture are examples of such causes [2] [1] [3].

Annotated Bibliography

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27

Siegrist's 1996 article on the adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions provides a basis for understanding the potential impact of stress in project management, highlighting the importance of balancing effort and reward to mitigate harmful health outcomes. According to the ERI model, excessive stress at work from high effort and little reward can result in harmful health outcomes like depression and cardiovascular disease. The author outlines many possible processes by which the ERI model may function and explores the empirical data that supports it. In order to reduce the occurrence of ERI in the workplace, the paper ends with suggestions for future study and interventions. The foundation for understanding the ERI model and its applicability to occupational health research and practice is provided by this fundamental study.

van Vegchel, N., de Jonge, J., Bosma, H. & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Reviewing the effort–reward imbalance model: drawing up the balance of 45 empirical studies. Social Science & Medicine, 60(5), 1117–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.043

This article by van Vegchel et al. provides an examination of the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) model, to understand the relationship between job demands and employee well-being, making it relevant to project management practices that seek to optimize the balance between workload and rewards. It is a thorough examination of 45 empirical studies that investigated the effort-reward imbalance model. The authors summarize the evidence for the model's central hypotheses, which include the negative health consequences of high-effort/low-reward conditions and the moderating effects of social support and personal characteristics. The review finds consistent support for the model's predictions, and the authors propose that the model can be used to better understand the relationships between work stressors and health outcomes. The study's findings have significant implications for occupational health, implying that interventions aimed at reducing effort-reward imbalance may be beneficial for promoting employee well-being.

Peter, R. (2002). Psychosocial work environment and myocardial infarction: improving risk estimation by combining two complementary job stress models in the SHEEP Study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 56(4), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.56.4.294

The study combines two job stress models, the Demand-Control and Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) models, to investigate the relationship between psychosocial work environment and myocardial infarction (MI) risk. The study highlights the importance of considering both the job strain and effort-reward imbalance models in estimating the risk of MI, indicating the relevance of psychosocial work environments on health outcomes and the need for effective stress management strategies in project management. The study examines MI risk in relation to the two models of job stress using data from the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP), a large population-based study. According to the findings, ERI is a better predictor of MI risk than demand control. The study adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the ERI model's role in predicting negative health outcomes, specifically cardiovascular disease. It emphasizes the significance of taking into account multiple job stress models when assessing risk in occupational health research.

Faragher, E. B. (2003). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(2), 105–112.

Faragher's meta-analysis investigates the link between job satisfaction and health. According to the study, job satisfaction is a significant predictor of overall health, specifically mental health, cardiovascular health, and general well-being. The analysis of the relationship between job satisfaction and health is relevant to project management, as employee job satisfaction has been shown to impact productivity and turnover rates, among other factors that can affect project success. The study also emphasizes the importance of including job satisfaction in occupational health research, as it has been found to be a better predictor of health outcomes than other job-related factors such as job demands or control. The findings of the study are consistent with the Effort-Reward Imbalance model, as a lack of reward in the workplace, which can lead to low job satisfaction, is a key factor in the model's prediction of negative health outcomes.

Stanhope, J. (2017). Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 67(4), 314–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx023

Stanhope's article provides a brief overview of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERI-Q), a tool used to assess the level of effort required at work and the rewards received in return. The questionnaire has three subscales: effort, reward, and overcommitment. The author discusses the ERI-Q's utility in identifying potential work-related stressors, particularly in the context of occupational health research. The article emphasizes the ERI-Q's practical application and its potential for improving working conditions by identifying and addressing job stressors. The ERI-Q is a useful tool for researchers and practitioners interested in investigating the relationship between work-related stress and negative health outcomes, particularly in the context of the effort-reward imbalance model.

Bakker, A. B., Killmer, C. H., Siegrist, J. & Schaufeli, W. B. (2000). Effort-reward imbalanceand burnout among nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(4), 884–891. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01361.x

Bakker et al. (2000) investigated the relationship between ERI and burnout in a sample of Dutch nurses. They discovered that ERI was significantly related to burnout, implying that nurses who experienced high effort and low reward were more likely to burn out. The study also discovered that social support mediated the relationship between ERI and burnout, implying that social support may mitigate the negative effects of ERI on burnout. This study emphasizes the ERI model's relevance in understanding the factors that contribute to burnout in healthcare professionals, as well as the potential importance of social support in mitigating the negative effects of ERI.

Koch, P., Schablon, A., Latza, U. & Nienhaus, A. (2014). Musculoskeletal pain and effort-reward imbalance- a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-37

Koch and colleagues conducted a comprehensive study to investigate the association between musculoskeletal pain and effort-reward imbalance (ERI) in diverse occupational categories. The evaluation included 24 papers that matched the inclusion criteria and found consistent evidence of a positive relationship between ERI and musculoskeletal pain. This relationship was especially high among healthcare and service industry workers. The authors conclude that lowering ERI in the workplace may lead to a reduction in musculoskeletal discomfort among employees. This study emphasizes the need of addressing not just psychological results but also physical health outcomes in the study of ERI and its influence on employees' health.

Kuper, H. (2002). When reciprocity fails: effort-reward imbalance in relation to coronary heart disease and health functioning within the Whitehall II study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 59(11), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.59.11.777

Kuper's research looked at the link between effort-reward imbalance (ERI) and coronary heart disease (CHD) as part of the Whitehall II study, a large-scale, prospective study of British public officials. The study discovered that ERI was a strong predictor of CHD, and this relationship remained even after controlling for numerous confounding factors. Furthermore, the study discovered that ERI was linked to lower physical and mental well functioning as determined by the SF-36 questionnaire. The study's findings are significant because they imply that ERI may have significant consequences for the development of chronic health disorders, as well as the necessity for measures to address ERI in the workplace to prevent bad health outcomes.

Peter, R., Siegrist, J., Stork, J., Mann, H. & Labrot, B. (1991). Zigarettenrauchen und psychosoziale Arbeitsbelastungen bei Beschäftigten des mittleren Managements. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin SPM, 36(6), 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01368738

Peter and colleagues investigated the association between smoking and psychosocial work stress in middle managers in a study. Data from a cross-sectional survey of 1.822 middle managers from diverse German organizations were used in the study. The effort-reward imbalance model revealed that psychological work stress was connected with an increased risk of smoking. Employees who encountered high levels of effort but low levels of reward, in instance, were more likely to smoke than those who did not experience such an imbalance. In efforts to reduce smoking incidence and related health concerns, this study emphasizes the significance of addressing not only individual risk factors, but also workplace factors such as psychosocial stresses.

Hautzinger, M. (2010). Akute Depression. Hogrefe Verlag.

Hautzinger's book about acute depression has little to do with the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) model. Depression, on the other hand, might be regarded an effect of ERI, since the model states that a lack of reciprocity between effort and reward can lead to chronic stress and, eventually, numerous health problems, including mental health concerns like depression. As a result, knowing the nature and treatment of depression can be useful in dealing with the consequences of ERI. Hautzinger's book gives an overview of the diagnosis, management, and prevention of acute depression, which may be useful for those who have ERI and are experiencing depression. The book can also shed light on how depression affects work-related outcomes such as productivity and absenteeism, both of which can be influenced by ERI.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 van Vegchel, N., de Jonge, J., Bosma, H. & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Reviewing the effort–reward imbalance model: drawing up the balance of 45 empirical studies. Social Science & Medicine, 60(5), 1117–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.043

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Peter, R. (2002). Psychosocial work environment and myocardial infarction: improving risk estimation by combining two complementary job stress models in the SHEEP Study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 56(4), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.56.4.294

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stanhope, J. (2017). Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 67(4), 314–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx023

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hanson, E. K. S., Schaufeli, W., Vrijkotte, T., Plomp, N. H. & Godaert, G. L. R. (2000). The validity and reliability of the Dutch Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.142

- ↑ Niedhammer, I., Siegrist, J., Landre, M. F., Goldberg, M., & Leclerc, A. (2000). Etude des qualites psychometriques de la version francaise du modele du Desequilibre Efforts/ Recompenses (Psychometric properties of the French version of the Effort–reward Imbalance model). Revue d’epidemiol et de sante publique, 48(5), 419–437.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Faragher, E. B. (2003). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta- analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(2), 105–112. .

- ↑ Greif, S., Bamberg, E. & Semmer, N. (1991). Psychischer Stress am Arbeitsplatz. Hogrefe

- ↑ Kauffeld, S., Ochmann, A. & Hoppe, D. (2019). Arbeit und Gesundheit. Springer-Lehrbuch, 305–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56013-6_11

- ↑ Honda, A., Date, Y., Maeta, S. & Honda, S. (2017). IMPACT OF EFFORT-REWARD-IMBALANCE ON PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS IN JAPANESE CARE STAFF. Innovation in Aging, 1(suppl_1), 1107. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.4055

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Stiftung Deutsche Depressionshilfe (2016). Zahlen und Fakten über Depression -AOK https://www.aok-bv.de/imperia/md/aokbv/presse/pressemitteilungen/archiv/2018/07_faktenblatt_depressionen.pdf

- ↑ Statistisches Bundesamt (2015) Gesundheit – Todesursachen in Deutschland Verfügbar unter:https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft- Umwelt/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Publikationen/Downloads-Todesursachen/todesursachen-2120400157004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile [01.05.2023]

- ↑ Hautzinger, M. (2010). Akute Depression. Hogrefe Verlag.

- ↑ Siegrist, J. & Marmot, M. (2006). Social Inequalities in Health: New Evidence and Policy Implications (1. Aufl.). Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Dick, T. B. (2020). Burnout, burnout, burnout is burning me out. Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, 3(3), 567–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jac5.1207

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bakker, A. B., Killmer, C. H., Siegrist, J. & Schaufeli, W. B. (2000). Effort-reward imbalanceand burnout among nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(4), 884–891. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01361.x

- ↑ de Jonge, J., van Vegchel, N., Meijer, T. & Hamers, J. P. H. (2001). Different effort constructs and effort-reward imbalance: effects on employee well-being in ancillary health care workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(1), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365- 2648.2001.3411726.x

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Siegrist, J., Starke, D., Chandola, T., Godin, I., Marmot, M., Niedhammer, I., & Peter, R. (2004). The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Social science & medicine, 58(8), 1483-1499.

- ↑ Grossarth-Maticek, R. & Grüntzig, A. R. (1979). Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie: Rauchen Übergewicht Emotionaler Stress (Delaware Edition) (1. Aufl.). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Peter, R., Alfredsson, L., Knutsson, A., Siegrist, J. & Westerholm, P. (1999). Does a stressful psychosocial work environment mediate the effects of shift work on cardiovascular risk factors? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 25(4), 376–381.https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.448

- ↑ Kuper, H. (2002). When reciprocity fails: effort-reward imbalance in relation to coronary heart disease and health functioning within the Whitehall II study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 59(11), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.59.11.777

- ↑ Koch, P., Schablon, A., Latza, U. & Nienhaus, A. (2014). Musculoskeletal pain and effort-reward imbalance- a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-37

- ↑ Koch, P., Kersten, J. F., Stranzinger, J. & Nienhaus, A. (2017). The effect of effort-reward imbalance on the health of childcare workers in Hamburg: a longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-017-0163-8

- ↑ Peter, R., Siegrist, J., Stork, J., Mann, H. & Labrot, B. (1991). Zigarettenrauchen und psychosoziale Arbeitsbelastungen bei Beschäftigten des mittleren Managements. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin SPM, 36(6), 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01368738

- ↑ Siegrist, J., & Wahrendorf, M. (2016). Work stress and health in a globalized economy: The model of effort-reward imbalance. Springer.