The Active Listening Technique

Written by Esther Kiara Pattipeilohy

Contents |

Abstract

Active listening is a communication technique that focuses on the message that is being conveyed by the speaker by taking the time to understand the speaker’s perspective, emotions and intentions [1]. This involves a variety of skills, such as showing empathy, paraphrasing and providing nonverbal feedback. The goal of active listening is to gain a deeper understanding of the speaker and their message to improve communication, trust and collaboration.

In project, portfolio and program management, active listening is an especially useful tool in enhancing communication and problem-solving and creating a more positive and dynamic team collaboration [2]. At the same time, it allows the project manager to make informed decisions, manage expectations and resolve conflicts. However, good management requires a variety of skills and approaches depending on the team, situation and project goal. Active listening should be used in combination with approaches such as brainstorming, mediation or collaborative problem-solving for the best results.

With more work and meetings being done online recently, it presents a challenge for practicing active listening, which for a large part relies on non-verbal and face-to-face communication. It is important to keep communicating verbally instead of only in text and to utilize visual aids in online meetings to increase non-verbal communication and increase the overall experience [3] [4].

Big Idea

Active Listening

Apart from speaking and writing, listening is one of the most important parts of communication. It is more than the physical process of hearing, it is an intellectual and emotional process, which requires hard work and concentration. Hunsaker and Alessandra classified people into four types of listeners; 1) non-listener, 2) marginal listener, 3) evaluative listener and 4) active listener. Each category requires different levels of concentration and sensitivity, going up with the numbers. Active listening (AL) is the most effective level of listening and is considered a special communication skill [5]. AL involves complete attention to what the speaker is saying, listening carefully while displaying interest and refraining from interrupting [6].

To be an active listener, one must listen for the content, intent, and feeling of the speaker, and show verbal and non-verbal cues that convey interest and importance [3]. Active listening is not typically used in rushed communication [5]. To be a good active listener, one should consider factors such as appropriate body movement and posture, facial expressions, eye contact, showing interest in the speaker’s words, minimum verbal encouragement, attentive silence, reflecting back feelings and content, and summarizing the speaker’s words and their purpose [7].

The Project Management Institute Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge [2] defines active listening as:

“Techniques of active listening involve acknowledging, clarifying and confirming, understanding, and removing barriers that adversely affect comprehension.”

Effective communication, particularly listening, is crucial for managers, as good listening is a key element of management success. Active Listening is applicable in all stages of the management of projects, programs, and portfolios. Communication is key in all aspects of managing projects and sending and receiving information happens all the time [2]. The ISO 21500 standard: Guidance on project management [8] claims that: “Success or failure of a project may depend on how well the various project team members and stakeholders communicate with each other” Researchers[9][10] claim that listening competencies are hugely important in managerial communication however, these are often forgotten when project management practitioners learn communications skills. As a consequence of this greater focus on delivering a message rather than how to receive one, project managers lack important listening skills[11]. As such, many organizations strive to enhance this skill in their managers [12]. Managers who listen actively demonstrate that they value their staff and customers, which helps to build trust and commitment in their work. This is in contrast to one-way communication, where managers simply issue orders [13]. Supervisors who possess better listening attitudes and skills can improve their communication with subordinates, leading to increased support and higher job satisfaction [14].

In management, AL can enhance interpersonal relationships, build confidence and respect, reduce tension, and create a better environment for joint problem-solving and sharing information within an organization [15]. Active Listening teaches you to stay engaged with the speaker and express a real interest in the person you talk to. This builds strong relationships with employees but it can also be used in another important aspect of project management: stakeholder management [2]. Analyzing stakeholders' expectations of the project requires that you are able to listen. When you listen, your stakeholders feel that they have been heard and their respect for you increases.

It is important to realize that, while active listening is a valuable tool for project management, it is not a must-have or a complete solution. Good project management requires a variety of skills and approaches, and the specific techniques used will depend on the situation, the team, and the goals of the project. Other techniques, such as brainstorming, mediation, or collaborative problem-solving, may be more appropriate according to the context.

Non-verbal Aspects

Active listening techniques go beyond being 'all ears', asking questions and using continuers, such as "hm mh". There are several non-verbal aspects that either support or limit your listening skills. Body language is also a way of communication and can be interpreted differently per individual[16]. For this reason, it is important to pay attention to your stance in order to communicate the right thing. For example, these things can hinder you in active listening practices:

- Crossed arms

- When listening to the other person, having your arms crossed may come over as disinterest in what is being said. It may also be interpreted as you being closed for suggestions.

- Fiddling

- Tapping the table or fiddling with a pen might look like impatience or disinterest. Keeping a calm facade is key for signaling interest.

- No eye-contact

- Staring out the window or looking at your phone limits you in focusing on what the other person is saying but it also shows that you are not paying attention, which can be interpreted as disrespect.

Other than the body language aspect of active listening, you should be aware of your position related to space; where you position yourself in the room, the way your body is facing and the distance you keep to the other person. Is it generally considered more comfortable if you mirror the other person in their position, sitting down when they are sitting down and standing up if they are standing up. Secondly, facing the other person with your whole torso instead of only your face is showing interest in what is being said. Lastly, it is important to respect their personal space, and not get too close. While paying attention to your own body language and position, you show be alert of this in the other person too. Their body language and position can tell you more than the actual words they are saying [17].

Another important non-verbal aspect is time. If you seem in a rush, the person you are having a conversation with may feel that you are not present or that they are being a burden, leading to them cutting the conversation short and sharing less of their true thoughts. As a project manager, you should create a context in which you have enough time to actively engage in the conversation with the employee or stakeholder [16].

Application

The technique

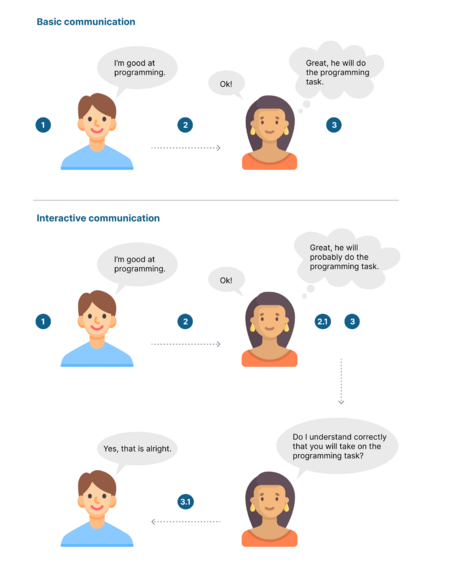

In a basic communication model, there are two actors: A sender and a receiver. The sender is the one who desires to deliver a message. Thus, in verbal communication, the sender is the speaker. The receiver is the listener in verbal communication, and thereby the one listening to the spoken message. In the basic communication model, the message is simply sent off by the speaker and then received by the listener. The responsibility for the success of the communication lies with the sender alone and their ability to send a clear message. This is different in an interactive communication model. Here the focus is not only on delivering a message but also on clarifying and confirming that it is understood correctly. This adds another two steps to the basic communication that makes it more interactive.

- 1 Encode

- The sender forms the message in words.

- Example: The employee decides on what to say and starts talking.

- 2 Transmission

- The message is sent or transmitted to the receiver.

- Example: The sound of the message travels from the mouth of the employee to the ears of the Project Manager.

- 2.1 Acknowledge

- This step takes place after the message has been transmitted to the listener. The listener lets the sender know, that the message has arrived. This can be done using body language or brief verbal affirmations.

- Example: The Project Manager nods his/her head to let the employee know, that the message has been received.

- 3 Decode

- The listener receives the message and translates the content.

- Example: The Project Manager hears the message and its immediate content. The Project Manager makes his/her own interpretation of the content.

- 3.1 Feedback

- After the listener has decoded the message, they encode their own interpretation of the message and transmit it back to the sender. This means that the listener formulates how they hear the message and send it back to the speaker to get a confirmation of whether it was understood correctly. The sender then verifies if the feedback matches the original message. If it does so, the communication has been successful.

- This step can only be performed if the receiver has strong listening skills and is able to hear what the speaker says. This also includes the elements of the message that exist between the lines or can be decoded from the speaker’s body language, cultural background, personality, etc.

- Example: The Project Manager says: “What I hear you say is this […], is that correctly understood?”. If the employee confirms that the Project Manager’s interpretation of the original message is correct, the communication has been successful.

In the interactive communication model, the Project Manager provides the employee with feedback and thereby gives him the option to further clarify the meaning of his message. This is a good technique to avoid any misunderstandings.

In this communication model, both the sender and the receiver carry the responsibility of successful communication. The speaker must be clear and concise when delivering the message. At the same time, the listener must ensure that all information is received, that the content of the message is interpreted correctly, and acknowledge and respond to the message appropriately. Effective communication only happens when both carry out their responsibilities, Michael Webb even argues that the listener bears more responsibility for the quality of the communication. Since listening is such an important, yet underestimated element of communication, it is hugely important for project management practitioners to learn good listening skills.

How to practice active listening

The primary thing to pay attention to when practicing Active Listening is the difference between hearing and listening. Hearing is a passive act while listening is active and engaging [18]. The overall mindset to apply when listening actively is to engage positively with the speaker. Here are some things to be aware of that will help you to become an active listener.

- Do not interrupt

- Do not interrupt the speaker. Do not try to finish their sentences even if you think that you know how they are going to finish them. If the speaker stops talking or pauses to search for the right way to phrase a sentence do not interrupt the silence. Stay quiet and let them think, they might surprise you with their answer. Pay attention to what the speaker says rather than focusing on what you are about to say [19].

- Be curious

- One of the main purposes of Active Listening is for you to learn more about the person in front of you as well as the content they share with you. One way to be curious is to ask clarifying questions about the knowledge you are provided with. This also assists in uncovering any misunderstandings in the communication. Asking questions shows the speaker that you are interested in what they tell you and that you hear what they are saying [20]. Ask the speaker to explain jargon or abbreviations that you do not know. The same word or abbreviation might mean something different to the speaker and the listener depending on their culture or work area.

- Provide feedback

- As described in the section above, providing feedback is a part of listening actively. Let the speaker know how you interpret their message and give them the option to correct any misunderstandings or miscommunications [2]. You can use phrases like: “What I hear you saying is …” or “Do I understand it correctly that …?” Take notes while the speaker talks so you have something to base your feedback on.

- Pay attention

- Try to focus on the person you talk to. Do not let yourself be disturbed by the environment around you or by distracting thoughts in your mind. When you focus actively on the speaker you will be able to pick up both verbal and non-verbal clues in the conversation that will assist you in decoding the message correctly [11].

- Do not judge

- Listen to the speaker even if you do not agree with what they say [19]. Do not let the physical appearance of the speaker disturb you. Do not let different cultural backgrounds, languages, areas of expertise, political opinions or the like affect how you interpret the message from the speaker.

- Show that you listen

- Show the speaker that you listen to them either by nodding your head, smiling or by small verbal affirmations from time to time. This lets the speaker know that you are engaged in the conversation. You can also focus on your body language. If you have an open posture you will seem more open and willing to take in the message [1]. Keep eye contact with the speaker.

Written / online practices

With remote work and online communication becoming a bigger part of the standard working environment, it is important for project managers to also know how to engage with employees in computer-mediated communication (CMC). Although it is no compensation for face-to-face meetings, there are active listening techniques that can be applied to online (telephone/webcam meetings) or written communication [4].

- Establishing eye contact

- It is imperative to have eye contact in discussions, especially during online meetings. Even though you are not in a face to face discussion, it is beneficial to stare and focus on your computer’s camera.

- Eliminating distractions

- Creating a clean and organized environment allows you to focus on the dialogue at hand. These distractions can include where you are meeting from, your computer tabs, and the outside environment.

- Jotting down notes

- Generally online meetings are difficult to stay concentrated in, so it is wise to scribble down short notes or critical points from the conversation. This enables you to stay focused in the present and gives you an opportunity to reflect in the future.

There are several advantages of the online setting when talking about good communication between project managers and employees. CMC leaves the control with the person who expresses their throughs, allowing them to completely verbalize their thoughts before responding[3].

Limitations

There is a multitude of factors that may impede someone's ability to listen with purpose and intention; these factors are referred to as listening blocks[21]. Some examples of these blocks include rehearsing, filtering, and advising. Rehearsing is when the listener is more focused on preparing their response rather than listening. Filtering is when a listener focuses only on what they expect to hear while tuning out other aspects of what is being said, and lastly, advising is when the listener focuses on problem-solving, which can create a sense of pressure to fix what the other person is doing wrong [22]. There are three types of barriers to effective listening: Environmental, Physiological, and Psychological [23].

- Environmental Barriers

- Environmental barriers are brought about by the speaker's environment. Some examples include noises, smells, bad cell reception, and any other factors that make it difficult to hear and process information. Sometimes it is due to the language the speaker uses—such as high-sounding and bombastic words that can lead to ambiguity. Other barriers include distractions, trigger words, vocabulary, and limited attention span. Environmental barriers likely can not be eliminated but they can be managed [23].

- Physiological Barriers

- Physiological barriers are those that are brought about by the listener's body. They can be temporary or permanent. Hearing loss and deficiencies are usually permanent boundaries. Temporary physiological barriers include headaches, earaches, hunger or fatigue of the listener. Another physiological boundary is the difference between the slow rate of most speech and the brain's ability to process that information. Typically, the brain can process around 500 words per minute while the average rate of speech for speakers is 125 words per minute. This difference makes it easy for the mind to wander [23].

- Psychological Barriers

- Psychological barriers interfere with one's willingness and mental capacity for listening. Pre-existing biases can lead to listening to someone else's argument for its weaknesses, ignoring its strengths. This can lead to a competitive advantage in a political debate, or by a journalist to provoke a strong response from an interviewee, and is known as "ambushing". Individuals in conflict often blindly contradict each other. On the other hand, if one finds that the other party understands, an atmosphere of cooperation can be created [23].

Overcoming the barriers to active listening

Being aware of the different barriers that exist to active listening will allow one to take preventive action in order to hinder these barriers from obstructing the listening skills [10]. Keeping these things in mind might help.

- Do not talk, just listen. The first step towards becoming an active listener is to put effort into actually listening to what is being said instead of speaking all at once.

- Use the nonverbal aspects of active listening to make the speaker comfortable by sitting down, having mild facial expressions, acknowledging the person so the person feels comfortable talking and elaborating on the meaning.

- Be prepared to listen and keep a positive attitude. This again refers to the nonverbal aspects, as body language is important here. Have a good posture, pay attention and even have pen and paper ready to note the key points and ideas.

- Eliminate distractions. Push away irrelevant thoughts, close the door to remove noise from the hall, put the phone down, and do not look at your watch or fidget with pens or paper.

- Try to put yourself in the shoes of the speaker. Show empathy and try to understand the speaker's point of view even though you might not agree.

- Have patience. When allowing the speaker to complete a speech the whole message will be delivered. Avoid making sarcastic comments, interrupting often or disturbing the speaker in other ways, as signs of impatience may hinder the speaker from opening up about the subject. Also, make sure to allow the speaker to pause and deliver the entire message without being interrupted

- Do not let your temper get away with you. Make sure to understand what the speaker is saying before reacting.

- Maintain eye contact, do not stare but make sure to focus on the speaking person as this shows genuine interest in listening which will encourage the speaker to continue.

Annotated bibilography

[1] - This article explores the attitude of eight different project managers toward Active Listening as a management tool. It shows that project managers generally express a positive opinion on the use of Active Listening and its effect on their daily work. The study also seeks to reveal whether listening is a forgotten element of managerial communication.

[3] - This paper investigates the application of active listening in written and online practices. The conclusion is that it is hard to fully engage in active listening in CMC, but there are certainly some things project managers can do to create a better communication.

[10] - It is important to sketch a realistic scenario of the tool, which includes the limitations and difficulties in usage. This article describes the barriers to active listening and how to overcome them. For a project manager it is useful to know how to practice active listening in demanding environments as well.

[11] - This article provides four categories of barriers to Active Listening. It presents a section that tell project managers how to remove some of these barriers and thereby get an audience’s attention. Hereafter, the article focuses on how project managers can improve their listening skills. It provides three steps for project managers to become better listeners and alludes to why it is important for a project manager to be an active listener.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Inga Jona Jonsdottir & Kristrun Fridriksdottir (2020) ACTIVE LISTENING: IS IT THE FORGOTTEN DIMENSION IN MANAGERIAL COMMUNICATION?, International Journal of Listening, DOI:10.1080/10904018.2019.1613156.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition), Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt011DXH02/guide-project-management

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bauer, Christine & Figl, Kathrin & Motschnig-Pitrik, Renate. (2009). Introducing 'Active Listening' to Instant Messaging and E-mail: Benefits and Limitations. IADIS International Journal on WWW/Internet. 7. 1-17. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229424196_Introducing_'Active_Listening'_to_Instant_Messaging_and_E-mail_Benefits_and_Limitations

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Danby, Susan, Butler, Carly, & Emmison, Michael (2009) When 'listeners can't talk': comparing active listening in opening sequences of telephone and online counselling. Australian Journal of Communication, 36(3), pp. 91-114. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/29064/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lopez, R., Balsa-Canto, E., & Oñate, E. (2008). Neural networks for variational problems in engineering. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 75. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Neural-networks-for-variational-problems-in-Lopez-Balsa-Canto/7abcd403f6fc0689d0123689ec0a18058b2c995b

- ↑ Harry Weger Jr., Gina R. Castle & Melissa C. Emmett (2010) Active Listening in Peer Interviews: The Influence of Message Paraphrasing on Perceptions of Listening Skill, International Journal of Listening, 24:1, 34-49, DOI: 10.1080/10904010903466311 Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10904010903466311

- ↑ Robertson, K. (2005). Active listening: more than just paying attention. Australian Family Physician, 34(12), 1053–5. Retrieved from https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.366629010280498

- ↑ International Standards (2012). ISO 21500:2012 Guidance on project management

- ↑ S. A. Welch & William T. Mickelson (2013) A Listening Competence Comparison of Working Professionals, International Journal of Listening, 27:2, 85-99, DOI: 10.1080/10904018.2013.783344 Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10904018.2013.783344

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Webb, M. (n.d.). Eight Barriers to Effective Listening. Retrieved from http://docplayer.net/52766786-Eight-barriers-to-effective-listening.html

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Bill Brantley (2012) Successful Project Managers Are Great Listeners. Retrieved from: https://www.govloop.com/community/blog/successful-project-managers-are-great-listeners/

- ↑ Kubota, S., Mishima, N., & Nagata, S. (2004). A Study of the Effects of Active Listening on Listening Attitudes of Middle Managers. Journal of Occupational Health, 46(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.46.60 Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1539/joh.46.60

- ↑ Cohen, S., Eimicke, W., & Heikkila, T. (n.d.). The Effective Public Manager. Google Books. Retrieved from https://books.google.dk/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=OelvAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&ots=AydQqTAKbE&sig=YmJHkAU_WUaoxpBABPjJ9az2J7o&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Mineyama, Sachiko & Tsutsumi, Akizumi & Takao, Soshi & Nishiuchi, Kyoko & Kawakami, Norito. (2007). Supervisors' Attitudes and Skills for Active Listening with Regard to Working Conditions and Psychological Stress Reactions among Subordinate Workers. Journal of occupational health. 49. 81-7. 10.1539/joh.49.81. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6399641_Supervisors'_Attitudes_and_Skills_for_Active_Listening_with_Regard_to_Working_Conditions_and_Psychological_Stress_Reactions_among_Subordinate_Workers

- ↑ Corissajoy. (2017, February 28). Empathic Listening. Beyond Intractability. Retrieved from https://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/empathic_listening

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Jacobs, G. (2016). Active listening. In A Practical Guide to Helping Individuals and Communities During Difficult Times. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-804292-2.00006-5

- ↑ Keyser, J. (2013). Active listening leads to business success. T And D, “67”(7), 26–28.

- ↑ Lewkovich, A. (2018). Hearing vs. Listening: What’s the Difference? https://www.yourtrainingprovider.com/hearing-vs-listening-whats-the-difference/#:~:text=Active%20vs.&text=Listening%20is%20an%20active%20process,developed%20over%20time%20with%20practice

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Goldstein, M. (2013). Mindful listening. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2013—North America, New Orleans, LA. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute

- ↑ Amanda Gore (2013) Joy Secret Number 8: Listening. Posted on the HuffPost Contributor platform. Retrieved from: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/joy_b_2313444

- ↑ McKay, M.; Davis, M.; Fanning, P. (2009). Messages: The communications skills book. Oackland, CA: New Harbinger. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/20183129/Downloads/1588067740-messages-the-communication-skills-book-by-matthew-mckay-phd-martha-davis-phd-patrick-fanning-z-lib%20(1).pdf

- ↑ Nemec, P.B.; Spagnolo, A.C.; Soydan, A.S. (2017). "Can you hear me now? Teaching listening skills". Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 40 (4): 415–417. doi:10.1037/prj0000287. PMID 29265860. S2CID 6112866. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fprj0000287

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Adler, Ronald B.; Elmhorst, Jeanne Marquardt; Maresh, Michelle Marie; Lucas, Kristen (2023). Communicating at work: strategies for success in business and the professions (13e ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-265-05573-8. OCLC 1245250324. Retrieved from https://www.worldcat.org/nl/title/1245250324