Challenges and Execution of Innovation Portfolio Management

Article Type 1: Explanation and Illustration of a Method

PUT IN: THIS REPORT TRIES TO GIVE AN INTEGRATED FRAMEWORK OF HOW TO APPROACH; NOT THE ONLY SOLUTION, BUT A WAY OF DOING IT

Innovation Portfolio Management (IPM) can be described as a dynamic decision process concept, in which an array of active innovation projects is constantly updated and revised to deliver innovation/innovative products to market.[1] [2] High-tech companies are nowadays faced with a business environment which is characterized by an increasing dynamism and unpredictability. In order to stay competitive it is crucial to develop a suitable and flexible innovation strategy by means of possessing a broad setup of innovation-projects (innovation portfolio) and permanently adjusting this portfolio to the changing environment.[3] Hereby IPM can deliver support as an appropriate tool to implement strategy shifts into all innovation-project activities throughout the organization in a coordinated manner. Main difficulties arising in the IPM process are related to the risk profile of basic innovation ideas, the continued innovation portfolio prioritization and to the dynamic resource allocation.[3]

This article focuses on describing the general structure of an IPM system integrated as a connecting element between qualitative strategy definition and the project-based implementation. The IPM is seperated into a strategic and operational element (Strategic and Operational Portfolio Management).[4] Hereby there are also given tools enabling to tackle the mentioned main challenges of investment risk (staging investment), portfolio prioritization (BCG matrix / McKinsey Matrix / R&D Project Portfolio Matrix)[5] and resource allocation (RCCP and RCPSP scheduling / RCMPSP scheduling / Agile / Critical Chain). The article is concluded with a short future outlook and open research questions.

Contents |

Innovation Portfolio Management (IPM)

General Idea and Impact

The basic idea IPM originates from is the Project and Portfolio Management Process (PPM). PPM is defined as a formal approach that an organization can use to orchestrate, prioritize and benefit from projects. This approach examines the risk-reward of each project, the available funds, the likelihood of a project's duration, and the expected outcomes. A group of decision makers within an organization, led by a Project Management Office director, evaluates the returns, benefits and prioritization of each project to determine the best way to invest the organization’s capital and human resources.[7] This article expands this conception by relating the portfolio management procedure to the innovation management (R&D) within high-tech companies. Thus PPM gets extended into the more dynamic IPM, which is a more complex, multi-level process specifically aiming at the continuous innovation management consistent with the corporate strategy.

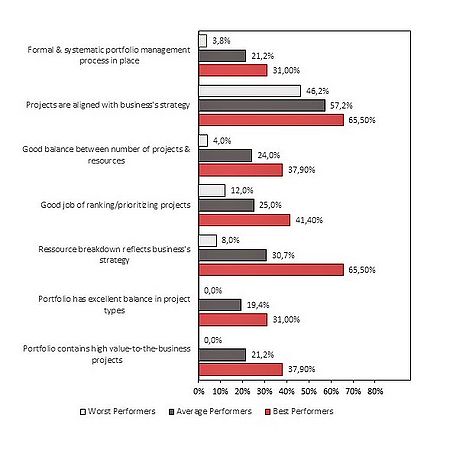

Traditionally innovation research was mainly focused on the appropriate management of single New Product Development (NPD) projects, thus focusing on innovation determinants at the project level.[2] In the face of today's globalization of markets, shorter life-cycles and increasing competition as well as complexity of technologies, high-tech firms have to hold a set of multiple NPD projects (innovation portfolio) to be flexible and reduce the risk to the lowest level possible. Hereby each project generates several changes on its own. This results in a set of cascading effects throughout the rest of the NPD projects, which have to be evaluated in relation to each other.[3] Additionally market changes and new business practices constrain firms to continuously reconsider the corporate competitive strategy, including their innovation portfolio. These two points create a permanently-changing decision context that cannot be conceived with a single-project perspective, but has to be managed with an overall IPM process. The desired outcome of an effective IPM is a stable pipeline of high-quality new products by linking the strategy formulation to the strategy implementation. This finally ensures long-term corporate growth and profitability.[2] In Figure 2 the best practices in portfolio management which have been observed in several studies and the impact of each practice are displayed, illustrating the positive impact of IPM on organizational performance. Despite the existence of this obvious interrelationship between corporate sustainable profitability and permanent innovation, many companies possess relatively conservative innovation strategies, rather focusing on maintaining and improving existing product lines.[2] The main reason for this mindset are the obstacles resulting from the extreme complexity of a well-implemented IPM process within an organization. In the following there is given a macro-overview of an IPM system to give the reader a good, general idea of the main structure and approach of an IPM system.

Main Challenges

In total there exist five main criteria characterizing effective IPM, making it one of the most complex decision-making functions within a firm:

- IPM is dealing with and dependent on future events and possible opportunities. The quality of the necessary information for project selection and prioritization decisions is in best case uncertain and in worst case unreliable.

- The environment for decision making is highly dynamic. Expectations and status of all projects within the innovation portfolio is continuously changing as markets shift and new information come up.

- All projects within the innovation portfolio are characterized by different levels of completion and compete for available resources (in this article resources are always related to human resources). Consequently a comparison among projects has to be conducted, based on information differing in quantity and quality.

- Available resources that can be allocated among the active projects are limited. Any prioritization of one project comes along with a deduction of resources for another project. Additionally resource transfers in real-world are not seamless as indicated by planning tools.

- Data availability over all the information gathered within the portfolio is critical. This further complicates an efficient and effective IPM process.[6]

Main Goals

As already mentioned in the chapter General Idea and Impact, the aimed final result of the IPM process for a firm is the delivery of high-quality innovations to the market. How does the IPM system itself have to be settled up to reach this organizational goal in the end? In research four main goals have been identified:

- Strategic Alignment is the goal with highest priority. Newly developed products have to match the corporate innovation strategy. This means that products need to support the strategy or even be critical components of it.

- Maximize the Portfolio Value means to maximize a portfolio value by allocating resources for a particular spending level. Thus the sum of the commercial value of all active innovation projects has to be maximized. Possible measurement possibilities are net present value (NPV, corresponds the difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows[8]), return on invest (ROI, measures the amount of return on an investment relative to the investment’s cost[9]) or likelihood of final success.

- Right Balancing of Projects relates to a number of project-specific parameters, that need to be balanced over the portfolio. Possible parameters to be balanced are long-term versus short-term projects, high-risk versus low-risk projects, market concentration or technology focus.

- The Right Number of Projects is a critical feature, especially due to the tendency that most companies have more projects running than their resources allow them to. Consequently there is a lack of human resources and time, leading to elongated time-to-market periods and a decreased quality of the delivered innovation products. Required resources for active projects and available resources necessarily have to be balanced. Possible approaches to ensure this are managing the key resource limits or the performance of a resource capacity analysis.[6]

Application of IPM

Organizational Setup

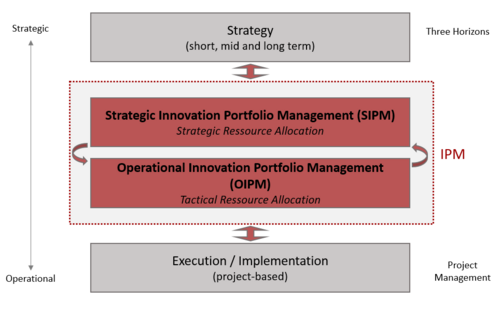

A good approach to unravel the complexity of IPM and break down the different challanges is the concept of dividing it up into a strategic and an operational part. SIPM aims at following the right innovation projects and supplying them with resources ("doing the right things"). OIPM on the other side ensures an appropriate execution of the selected projects ("doing things right"). As stated, the IPM concept enables a company to permanently link the strategy development to execution in order to generate tangible results. Exactly at this linkage, between strategy definition and metrics-based project execution, SIPM and OIPM are positioned. The resulting arrangement is illustrated in Figure 2, with the overall IPM system in the grey box as "transmission" element.[1] To achieve a structured form of organizing the IPM, a portfolio governance in form of a Project Portfolio Management Office (PPMO) should be installed on the strategic level. This PPMO is responsible for the SIPM and has the effect of increasing IPM quality and as a consequence of that also the portfolio success, as studies have revealed.[2] TBD: it-system

Strategic Innovation Portfolio Management (SIPM)

Balancing Portfolio

The intended state of a balanced portfolio is defined as an assortment of innovation projects enabling sustainable growth and profit for a company associated with its corporate strategy without being exposed to undue risks. Maintaining such a kind of balance leads to an asset base of technologies, which are essential for competitive advantage.[5]

First, the selection of projects and new innovations has to be decided carefully. Accordance with the corporate direction of strategy has highest importance. Especially for long-term projects this criteria has to be emphasized in particular, as they are shaping and representing the long-term strategy.[5]

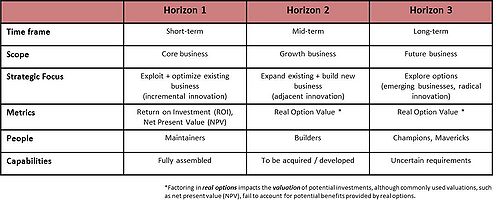

In a second step the coverage of both, long-term and short-term innovation projects has to be balanced. A good method for achieving such a "project mix" is to define the three "horizons" "Short-term", "Mid-term" and "Long-term" helping to distinguish and manage innovation activities across different time frames. An exemplary outline of such a managing-model is displayed in Figure 3 together with the corresponding characteristics for each horizon. This method supports the IPM management to not loose track of pushing forward mid- and long-term innovation investments due to unintentional focus on the short-term performance. Typically it is mainly the horizon 2 activities, which get neglected due to their position between the two extremes short-term budgets and long-term focus. Finally a good balance in this category is accomplished by a parallel process of future business identification and development along with optimization of the existing business.[1]

The third crucial criterion to be balanced regarding the portfolio is risk and uncertainty. For every project exists the risk of not meeting the specified objectives and there can always arise challenges from the outside. To analyse the risk of a single project, it has to be decomposed into component activities resulting in the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). Hereby the decomposition can range, depending on the necessary depth of the analysis, from a simple WBS for horizon 3 projects to a complex WBS for a project standing in horizon 1. In this way the risk for all project activities can be solely analysed, in order to afterwards estimate the corresponding probabilities and consequences.[10] New literature claims that a in a IPM framework the risk-estimation of single projects is not sufficient anymore suggesting a portfolio-wide risk management. Such an approach supports the alignment as well as redistribution of resources between projects enhancing portfolio transparency. Also a portfolio-wide risk management is capable to identify in multiple projects simultaneously arising risks, which gives the possibility to consolidate activities and prevent double-work. Thus possible failure can be avoided and the possibility of project success is increased. On the other hand it has to be considered how complex and expensive the implementation of such a kind of system is. Also research on risk management and the associated success in a innovation project portfolio context is a pretty young discipline. These two points and the acknowledged positive effects of single project risk management in literature make portfolio risk management so far a very rarely implemented system.[11] A possibility to further complement the single project risk management is a staging investment approach across the innovation portfolio depending on the risk of each project. This implies to on the average make high bets (investments) rather in horizon 1, medium bets in horizon 2 and low bets in the high-risk and uncertain horizon 3. This clarifies the importance of prototyping, pilot projects and market research, as they are necessary to afterwards scale projects up. A time-proven guideline for the allocation of innovation funds is 70% for horizon 1, 20% for horizon 2 and 10% for horizon 3 projects.[1]

Cyclic Innovation Portfolio Evaluation and Prioritization

Cyclic innovation portfolio evaluation and prioritization is a dynamic decision process in the SIPM, in which the innovation portfolio is constantly updated and revised. In detail this means that new projects are evaluated, selected and prioritized, existing projects are upgraded, deprioritized, or even killed, and resources may be allocated and reallocated to active projects within the portfolio. This procedure is basically adopted from the multi-project based process of PPM. Main challenges within this process are uncertain information about project states, the identification of project synergies, changing opportunities evolving in the business environment and conflicting strategic goals of the firm. It is essential to update a company's portfolio by this process regularly and efficiently to prevent heavy resource bottlenecks in the innovation portfolio pipeline. As the projects within the portfolio can be based in different units within a company, this process also has to account for the different interdependencies.[2][3] The decisions made in this context also have a relatively heavy impact on a company's innovative capability and thus also on the company's sustainable growth and profitability. That is why the innovation projects have to be subjectively evaluated from strategic managers with different backgrounds and functions, which are able to find for a particular firm the best consensus regarding specifications and goals. This circle of deciders corresponds the already mentioned PPMO.[5]

Many quantitative and qualitative methods for project- and portfolio assessment were discussed in the literature, ranging from operations research methods to social-science-based approaches. Proposals for project selection and prioritization were mainly focusing on one of the following methods:

- Unstructured peer review

- Scoring methods

- Mathematical Programming (e.g. linear / non-linear programming)

- Economic Models (e.g. internal rate of return)

- Decision analysis (e.g. analytic hierarchy process)

- Artificial intelligence (e.g. expert systems)

The combination of different approaches via an interactive, computer-based Decision Support System (DSS) is also a possibility, giving decision makers the possibility of simulating different scenarios in an user-friendly way or prioritize concerning special goals (e.g. main focus on strategic alignment[12]). The most suppressing fact of most research approaches is their extreme mathematical complexity, making the assistance of an expert decision analyst necessary for a "normal" manager to use such a system.[13]

The most common way, and also the most the reasonable way concerning the macro-perspective and dimension of this article, are scoring methods. They enable the deciders to quickly find the projects with the highest merit without being completely dependent on early estimates. There exist many indicators which possibly can be applied in the scoring model. The identification, emphasis and number of such success factors for an innovation is a very demanding task making it part of big research efforts over the last decades. Depending on the competitive structure of a market, each industry is confronted with a particular array of challenges, which are not relevant at all to other industries. Consequently there exists a particular set of scoring criteria which have to be applied for the decision process, unique to each firm.[5]. A good "basic" set of reasonable criteria to build a scoring model around are "benefits", "cost", "risk", "market share", "technical feasibility" and "margin", covering the most important aspects to consider.[14]

If a less detailed, rather fast overview of the potential of projects is demanded, different analytical tools with different approaches and focus areas can be used. Examples are the Boston Consulting Group Growth-share Matrix (BCG Matrix) and the McKinsey Matrix. These tools are mainly focusing on two, maximum three indicators in order to facilitate a depiction of the analysis. So the BCG Matrix uses relative market share and industry growth rate in a four-cell matrix as success determinants, whereas the McKinsey Matrix focuses on competitive position of a company and industry attractiveness within a nine-cell matrix. These tools however have to be used carefully as they cannot capture the complexity of a innovation portfolio decision process. So criticism of the matrices addresses among others the difficulties of measuring the chosen indicators, a lack of market structure consideration, the high uncertainty and the approach of viewing the portfolio as a closed system.[5]

No matter which approach for decision making is used, it is just a tool and should never completely replace personal management judgment and leadership. There should always be space for exceptional decisions, such as funding an innovation project which does not meet the scoring requirements. This gives the priority list of projects a final fine-tuning. After such kind of decisions however a transparent communication throughout the organization, as well as to customers and stakeholders is important.[13][15]

In order to implement the prioritization of the innovation portfolio, the next step is to (re)allocate the available resources in accordance to reach full alignment. Otherwise the consequent tactical OIPM cannot reach success. Strategic resource management aims to translate resource availability into corresponding constraints and implement these constraints into the analysis of alternative portfolio composition. In case a proposed innovation portfolio and its prioritization are not feasible with the available resources, the portfolio has to go through a second decision process or the magnitude of the resource pool needs to be adjusted (e.g. by hiring).

Operational Innovation Portfolio Management (OIPM)

Tactical Resource Allocation

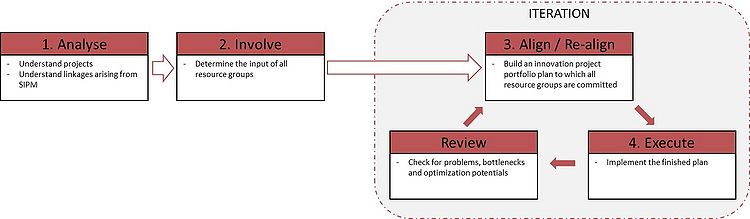

The main goal of the OIPM is to execute the strategic portfolio decision efficiently. This requires integrated planning, managing of project interdependencies, tactical resource allocation as well as distribution of hard- and soft-skills across the project requirements. As there occur numerous dynamic changes within the portfolio along with new interrelationships, a permanent high-quality OIPM is required to deliver project results and efficiency in doing so. As orientation the key sequence "analyse", "involve", "align" and "execute" can be taken as red line for the whole process, incorporating a mixture of analysis, IT processes and intense communication. It should be highlighted that this part of the IPM is the most people-driven process, making it also a very vulnerable one. In Figure 4 the key sequence is displayed together with a dynamic iteration loop . In order to achieve engagement and correlated with that motivation of all involved resource groups they should be taken into consideration during the build-up of the innovation project portfolio plan and the related resource allocation. During the permanent reviewing of the ongoing process the amount of analysed date should be kept at a reasonable level, meaning to keep the whole system agile instead of bureaucratic and sluggish.[1]

==

GUTE FORMULIERUNG: Project portfolio selection is the periodic activity involved in selecting a portfolio, from available project proposals and projects currently underway, that meets the organization's stated objectives in a desirable manner without exceeding available resources or violating other constraints.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 R.C. Ohr, K. McFarthing, Managing Innovation Portfolios - Strategic Portfolio Management, (InnovationManagement.se, 2013), http://www.innovationmanagement.se/2013/10/11/managing-innovation-portfolios-operational-portfolio-management/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 A. Meifort, Innovation Portfolio Management: A Synthesis and Research Agenda, Creativity and Innovation Management, 25 (2016): 251-296.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 R. Abrantes, J. Figueiredo, Resource management process framework for dynamic NPD portfolios, International Journal of Project Management, 33 (2015): 1274-1288.

- ↑ R.C. Ohr, K. McFarthing, Managing Innovation Portfolios - Operational Portfolio Management, (InnovationManagement.se, 2013), http://www.innovationmanagement.se/2013/09/16/managing-innovation-portfolios-strategic-portfolio-management/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 J.H. Mikkola, Portfolio management of R&D projects: implications for innovation management, Technovation, 21 (2001): 423-435.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 S.J. Edgett, Portfolio management for product innovation, The PDMA handbook of new product development, (2013): 154-166.

- ↑ Definition - Project- and Portfolio Management, (TechTarget, 2015), http://searchcio.techtarget.com/definition/PPM-project-and-portfolio-management.

- ↑ Definition: Net Present Value (NPV), (Investopedia, 2016), http://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp.

- ↑ Definition: Return on Investment (ROI), (Investopedia, 2016), http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/returnoninvestment.asp?ad=dirN&qo=investopediaSiteSearch&qsrc=0&o=40186.

- ↑ N.P. Archer, F. Ghasemzadeh, An integrated framework for project portfolio selection, International Journal of Project Management Vol. 17, 4 (1999): 207-216.

- ↑ J. Teller, A. Kock, An empirical investigation on how portfolio risk management influences project portfolio success, International Journal of Project Management, 31 (2013): 817-829.

- ↑ L.M. Kipper, The Use of Scoring Method for Prioritizing, Jorunal of Management Research Vol.6, 1 (2014): 156-169.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 A.D. Henriksen, A.J. Traynor, A Practical R&D Project-Selection Scoring Tool, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management Vol.46, 2 (1999): 158-170.

- ↑ D. Blumhorst, Principles of Scoring Models, (PM times - Resources for Project Managers, 2013), https://www.projecttimes.com/articles/principles-of-scoring-models.html.

- ↑ C. Gosenheimer, Project Prioritization - A Structured Approach To Working On What Matters Most, Office of Quality Improvement - University of Wisconsin-Madison,(2012).