Integrating Mindfulness in Project and Program Management

Mindfulness is a state of consciousness in which attention is focused on present-moment phenomena occurring both externally and internally.[1] This present-moment phenomena can also include embarking in creative imagination about the future, problem solving in the present or analysis of the past - as well as a discerning capacity of observing the present situation and context without falling into habitual tendencies or routines. This targets a number of challenges for Project and Program managers in where, due to time pressure, uncertainty and personal cognitive biases, sub-optimal decisions are often made highly impacting the projects outcomes.

This article intends to build upon the growing number of theories and evidences of the benefits of mindfulness, from two perspectives: individual and collective. It will draw from the latest research on the topic and link it to the existing framework for Mindfulness in High Reliability Organizations (HRO), developed by professors Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. Finally, the article will finish by suggesting potential tools and areas of integration for Project and Program Managers practice.

Contents |

Context

Historical definition of Mindfulness

The earlier account of the meaning of the world mindfulness comes from the Pali-term sati, simply meaning a state of non forgetfulness, bearing in mind a given object of attention. This includes retrospective memory of things in the past; prospective memory, to remember to do things in the future; and present centered recollection in the sense of maintaining attention to the present reality. [2]

In several contemplative traditions mindfulness this mental factor is viewed as a pre-requisite to: 1) Develop attention/concentration skills 2) Develop empathy and altruism; and 3) Developing cognitive balance. The latter can be generally understood as the self-awareness of our own internal mental processes, cognitive biases and tendencies, and the degree of freedom to which an individual can refrain from acting on them.[3]

Mindfulness in the West

Even though there are earlier accounts of Mindfulness in the West, the recent popularity of the concept of Mindfulness in the West is generally attributed to Jon Kabbat-Zinn and his work on Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programme. The adoption of mindfulness related practices/training has been widespread, ranging from training and development programs of major corporations from Google to General Mills, to programs in prisons to prevent work burnout of juvenile guards.

Universities, too, have taken up the call. For example, the director of mindfulness education at UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center leads on average 200 people every week in a silent Mindfulness Awareness meditation class held at the Hammer Museum’s Billy Wilder Theater [4]

Recent research

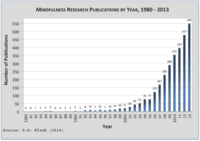

The past 30 years have seen exponential growth in research of Mindfulness. Much research concerned with the development of individual-level mindfulness maintains that mindfulness can be developed through meditation. The research takes its cue from Jon Kabat-Zinn's MBSR programme but also a variety of other Mindfulness Based Interventions (MBIs) i.e.: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy [5]

Building on the view that mindfulness is a byproduct of meditation experimental research has shown that state mindfulness can be activated through brief meditation-related instructions and exercises [6] [7]

The growth in mindfulness research literature from 1980-2013 is shown in the graph at the right-handside.

Individual Mindfulness

| Definitions | Source |

|---|---|

| A state of consciousness in which attention is focused on present-moment phenomena occurring both externally and internally | Dane (2011, p.1000)[1] |

| A meta-cognitive ability defined as "a state of being attentive to and aware of what is taking place in the present" and involves conscious perception and processing of external stimuli (in contrast to automatic tendencies) | Eisenbeiss & van Knippenberg (2015) [8] |

| A state of consciousness in which individuals pay attention to the present moment with an accepting and nonjudgemental attitude | Brown et al. 2007, Kabat-Zinn 1994 [9] [10] |

| An active state of mind characterised by a novel distinction-drawing that results in being (a) situated in the present, (b) sensitive to context and perspective, and (c) guided (but not governed) by rules and routines | Langer (2014, p. 11) [11] |

Benefits of Individual Mindfulness

Different research on mindfulness has proved its varied impacts on health, performance and emotional regulation. Some of the key findings presented include:

- enhanced psychological and physical well-being [9]

- slow aging (Epel et al. 2009)

- improve standardised test performance (Mrazek et al. 2013).

- Research has demosntrated that meditative training programs reduce work-related stress (e.g., Bazarko et al. 2013, Wolever et al. 2012).

- Hulsheger et al. (2013) found through a field experiment with working professionals that mindfulness reduced emotional exhaustion and increased job satisfaction.

Even more relevant to our case in point, organisational research indicates that individual mindfulness is positively related to employee outcomes such as:

- Work engagement (Leroy et al. 2013) and

- Job performance:

- One a study of nuclear power plant operations found found that trait mindfulness was positively related to job performance for operators who held jobs high in task complexity Zhang et al. (2013)

- Another study found a positive relationship between workplace mindfulness and job performance among those working in a dynamic performance environment (the restaurant service industry) that remained significant when controlling for three dimensions of work engagement. (Dane & Brummel 2014).

Furthermore, Reb et al. (2015) found positive relationships between work-related mindfulness and task performance and organizational citizenship behavior, respectively, within their survey of working adults. Also relevant to overall performance, Eisenbeiss & van Knippenberg (2015) found that employees high in trait mindfulness responded more strongly to ethical leadership in terms of the effort and helping behaviors they put forth. This suggests that, in the presence of an ethical leader, individuals high in trait mindfulness are more likely to perceive and embrace the values and behaviors they perceive in ethical leaders and to perform accordingly. Mirroring this finding, through a pair of cross-industry, survey-based studies, Reb et al. (2014) found that the trait mindfulness of supervisors is positively related to the well-being and performance of their employees.

These findings suggest that the mindfulness of one person in an organization can influence the well-being and performance of others and also that individual mindfulness practice can have an impact accross all levels of organization, ranging from strategic and tactical to operational. Suggesting the mindfulness contributes to an organisation's bottom line.

Collective Mindfulness

Collective mindfulness was originally developed to explain how high-reliability organizations (HROs) avoid catastrophe and perform in a nearly error-free manner under trying conditions. Over time, the focus has expanded to include "organizations that pay close attention to what is going on around them, refusing to function on ‘auto-pilot’”. Collective mindfulness is a means of engaging in the everyday social processes of organizing that sustains attention on detailed comprehension of one’s context and on factors that interfere with such comprehension (Vogus & Sutcliffe 2012; Weick et al. 1999; Weick & Sutcliffe 2001, 2006, 2007).

Some of the most common definitions of Collective Mindfulness highly influenced by Weick et al work are the following:

| Definitions | Source |

|---|---|

| To stay mindful, despite hazardous environments, frontline employees consider constantly five principles: tracking small failures, resisting oversimplification, remaining sensitive to operations, maintaining capabilities for resilience, and taking advantage of shifting locations of expertise | Ausserhofer et al. (2013, p. 157) |

| Actively and continuously question assumptions; promote orderly challenge of operating routines and practices so successful lessons of the past do not become routine to the point of safety degradation; “outside view” actively solicited or created through active multidisciplinary review of the routine and debriefing of the unusual to prevent normalization of deviance | Knox et al. (1999, p. 26) |

| The combination of ongoing scrutiny of existing expectations based on newer experiences, willingness, and capacity to invent new expectations based on newer experiences, willingness and capacity to invent new expectations that make sense of unprecedented events, a more nuanced appreciation of context and ways to deal with it, and identification of new dimensions of context to improve foresight and current functioning | from Weick & Sutcliffe 2001, p. 42) |

| Mindfulness refers to processes that keep organizations sensitive to their environment, open and curious to new information, and able to effectively contain and manage unexpected events in a prompt and flexible fashion | Valorinta (2009, p. 964) |

Benefits of Collective Mindfulness

Investigation on the employee and organisational consequences of collective mindfulness - defined as the collective capability to discern discriminatory detail about emerging issues and to act swiftly in response to these details (Weick et al. 1999, 2000; Vogus & Sutcliffe 2012) - and, in doing so, have found an array of benefits. For employees,

- mindful organising is associated with lower turnover rates (Vogus et al. 2014a).

For organisations, collective mindfulness is positively related to salutary organisational outcomes including:

- more effective resource allocation (Wilson et al. 2011);

- greater innovation (Vogus % Melbourne 2003);

- improved quality, safety and reliability (e.g., Vogus & Sutcliffe 2007a,b).

Interestingly, these effects are most commonly observed in particularly trying contexts charactered by complexity, dynamism, and error intolerance. This suggests that some of these benefits can be achieved even in the toughest project and programs situations.

Why is it important? The Impact of Human Behaviour on Project and Program Management

Independent of the actual complexity of a project is the way we perceive and manage this complexity. Arguably, regardless of the project's "real” complexity, what count are our perception and reaction to it. [12]

Cite error:

<ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found