Scenario Analysis

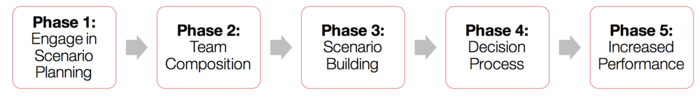

Scenario Analysis or Scenario Planning is a tool for project, programme and portfolio uncertainty management. Since its origin in war games and refinement by Shell the mid twentieth century, scenario planning has developed from a fairly quantitative methodology with close ties to game theory, to a more qualitative tool. (Roxburgh, 2009) In the same period, scenario planning has possibly also become increasingly important, in an era where innovation and disruption has had everyone looking for the next way to flip over the table in the ever-changing markets. (Amer, 2012) It is in the same instance that scenario planning becomes most valuable, enabling organisations to prepare for whatever the future might bring, thus not merely offering a better chance of surviving potential dramatic changes by mitigating risks, but in some cases also take advantage of said changes. Managing projects, programmes, or portfolios, scenario planning aids preparing the best strategy, making contingency plans or even just reflect on how the environment will look in the future.

Contents |

Big Idea

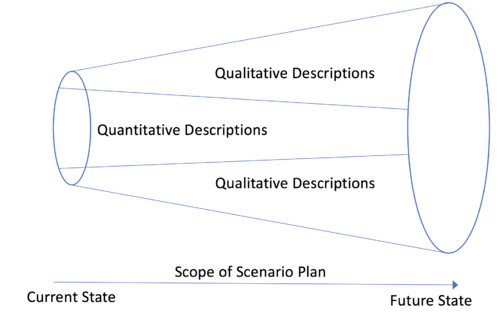

Scenario planning aggregates various projections of technical and non-technical factors into a consolidated overview of plausible futures, thus allowing for broader as well as more profound consideration of the future environments that may emerge. (Ford, 2012) Thus, it will help putting the process at hand into perspective, and enable to set success criteria for the future instead of now (Tonnquist, 2009).

The usage of scenario planning grew in the 1970’ies as the dramatic volatility of the oil prices woke up organisations that have lived off forecasts since the forties (an unusually smooth economic period) along with a growing belief in the non-rational side of human nature.

The attractiveness of the method increased further to 70 % of companies using in the aftermath of the 9/11 and the unstable global view. It is supposedly even due to scenario planning performed by New York Board of Trade in the 90’ies, that a third trading floor was established a few years before the 2001 terrorist attack, ensuring that the world trade could keep going. (Economist, 2008)

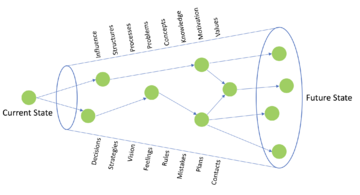

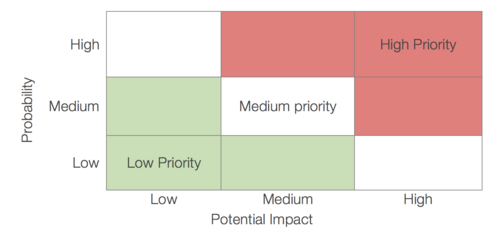

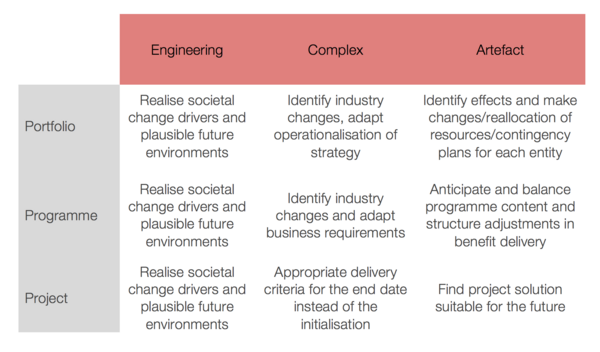

Scenario planning should not be mistaken for forecasts. Forecasting assumes that the future will look like the recent past, making it suitable for near future planning, but on longer terms chances are that the surrounding environment has changed. (Future Freight Flows MIT, 2011) Realising how misleading predictions based on straight-line extrapolations from the past are, scenario planning can aid identifying and adapting to aspects changing in the surrounding environment, by regarding a wide range of disciplines, including; economy, psychology, politics and demographics, all relevant factors when managing portfolios, programmes, or longer projects (see figure 1). Another relevant discipline that uncertainty management imbricates with is risk management, however with some basic differences. Risks are always negative, the probabilities are known, thus rational decision making can be made on how to handle them, whether that is mitigating actions, monitoring, or management and contingency planning. Uncertainties on the other hand, are not necessarily bad, but the probabilities are unknown, thus scenario planning is useful. It is important not to see scenarios as only either good or bad, but nuanced plausible futures to operate in. (Roxburgh, 2009) Furthermore, it is valuable because it may change the idea that the future will resemble the past and only gradually change, by demonstrating how things could change for the better or worse, by asking why the past may not be helpful (’09 crisis), and thus increase the readiness for what the future brings. Additionally, it can help avoid groupthink and challenge the carefully thought out strategy, that in some companies is conventional wisdom that no one dares to question (Roxburgh, 2009).

Lastly, is important to note that scenario planning is not specific to industry, system level, project, programme, or portfolio management, but can be purposefully applied in many different instances. For instance, a narrow subject like whether an organisation should make a particular investment, or a wider like whether the Danish educational system will be affected by changing demographics. (Economist, 2008)

Application

- None of the above is rocket science. Why, then, don’t people routinely create robust sets of scenarios, create contingency plans for each of them, watch to see which scenario is emerging, and live by it? Scenarios are in fact harder than they look—harder to conceptualize, harder to build, and uncomfortably rich in shortcomings. A good one takes time to build, and so a whole set takes a correspondingly larger investment of time and energy. Scenarios will not provide all of the answers, but they help executives ask better questions and prepare for the unexpected. And that makes them a very valuable tool indeed.

- -Roxburgh, 2009

Limitations

Annotated Bibliography

References

- Hindle, T., (2008), “Scenario Planning”, The Economist, [ONLINE] available at: http://www.economist.com/node/12000755

- Roxburgh, C., (2009), “The use and abuse of scenarios” [ONLINE] available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-use-and-abuse-of-scenarios

- Caplice, C. (2011), “Introduction to Scenario planning”, Future Freight Flows (FFF) Project at MIT [ONLINE] available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVgxZnRT54E

- Boasson, Y., (2004), “An Evaluation of Scenario Planning for Supply Chain design”, Massachusetts Institute of Technology [ONLINE] available at: http://ctl.mit.edu/sites/ctl.mit.edu/files/library/public/theses_2004_Boasson__execsumm.pdf

- Seal, W., Garrison, R. H., & Noreen, E. W. (2012). Management Accounting(4th ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Ford, D., & Saren, M. (2012). Managing & Marketing Technology . Hampshire, United Kingdom: Cengage Learning.

- Tonnquist, B. (2009). Project management: a complete guide. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Muhammad Amer, Tugrul U. Daim, Antonie Jetter, A review of scenario planning, Futures, Volume 46, 2013, Pages 23-40