Scenario Analysis

Scenario Analysis or Scenario Planning is a tool for uncertainty management, for instance in project, programme and portfolio management. Since its origin in war games and refinement by Shell the mid twentieth century, scenario planning has developed from a fairly quantitative methodology with close ties to game theory, to a more qualitative tool. (Roxburgh, 2009) In the same period, scenario planning has possibly also become increasingly important, in an era where innovation and disruption has had everyone looking for the next way to flip over the table in the ever-changing markets. (Amer, 2012) It is in the same instance that scenario planning becomes most valuable, enabling organisations to prepare for whatever the future might bring, thus not merely offering a better chance of surviving potential dramatic changes by mitigating risks, but in some cases also take advantage of said changes. Managing projects, programmes, or portfolios, scenario planning aids preparing the best strategy, making contingency plans or even just reflect on how the environment will look in the future.

Contents |

Big Idea

Scenario planning aggregates various projections of technical and non-technical factors into a consolidated overview of plausible futures, thus allowing for broader as well as more profound consideration of the future environments that may emerge. (Ford, 2012) Thus, it will help putting the process at hand into perspective, and enable to set success criteria for the future instead of now (Tonnquist, 2009).

The usage of scenario planning grew in the 1970’ies as the dramatic volatility of the oil prices woke up organisations that have lived off forecasts since the forties (an unusually smooth economic period) along with a growing belief in the non-rational side of human nature.

The attractiveness of the method increased further to 70 % of companies using in the aftermath of the 9/11 and the unstable global view. It is supposedly even due to scenario planning performed by New York Board of Trade in the 90’ies, that a third trading floor was established a few years before the 2001 terrorist attack, ensuring that the world trade could keep going. (Economist, 2008)

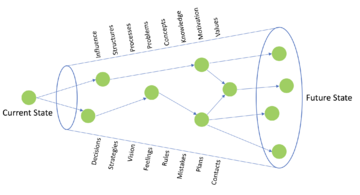

Scenario planning should not be mistaken for forecasts. Forecasting assumes that the future will look like the recent past, making it suitable for near future planning, but on longer terms chances are that the surrounding environment has changed. (Future Freight Flows MIT, 2011) Realising how misleading predictions based on straight-line extrapolations from the past are, scenario planning can aid identifying and adapting to aspects changing in the surrounding environment, by regarding a wide range of disciplines, including; economy, psychology, politics and demographics, all relevant factors when managing portfolios, programmes, or longer projects (see figure 1). Another relevant discipline that uncertainty management imbricates with is risk management, however with some basic differences. Risks are always negative, the probabilities are known, thus rational decision making can be made on how to handle them, whether that is mitigating actions, monitoring, or management and contingency planning. Uncertainties on the other hand, are not necessarily bad, but the probabilities are unknown, thus scenario planning is useful. It is important not to see scenarios as only either good or bad, but nuanced plausible futures to operate in. (Roxburgh, 2009) Furthermore, it is valuable because it may change the idea that the future will resemble the past and only gradually change, by demonstrating how things could change for the better or worse, by asking why the past may not be helpful (’09 crisis), and thus increase the readiness for what the future brings. Additionally, it can help avoid groupthink and challenge the carefully thought out strategy, that in some companies is conventional wisdom that no one dares to question (Roxburgh, 2009).

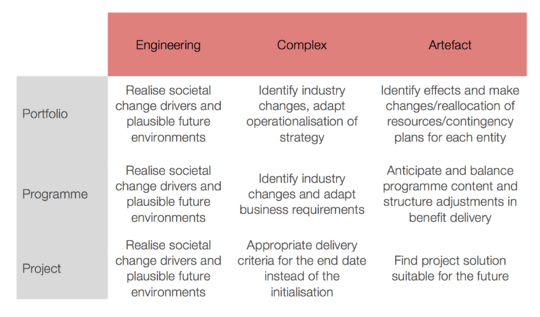

Lastly, is important to note that scenario planning is not specific to industry, system level, project, programme, or portfolio management, but can be purposefully applied in many different instances. For instance, a narrow subject like whether an organisation should make a particular investment, or a wider like whether the Danish educational system will be affected by changing demographics. (Economist, 2008)

Application

Generic Scenario Planning Model

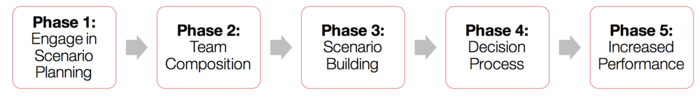

As previously mentioned, there is currently no industry standerd model for scenario planning. (Keough, 2008) However, Keough and Shanahan has built a generic scenario planning model consisting of five phases, which is the methodology this article will focus on. (Amer, 2012)

The five phases can be seen subsequently.

- Engage in Scenario Planning:

- The initial activity is to examine internal and external factors to determine whether scenario planning is an appropriate tool. This includes establishing if the organisation culture is equipped to make use of it; if a suitable long-term time perspective is defined; and if senior management supports the use.

Other factors, such as organisational structure, costs, and industry dynamics also play a role.

- Team Composition:

- The team composition of the team executing the scenario planning is critical in order to return capable, realistic scenarios with a wide range of insights and considerations. Teams should consist of participants with different backgrounds, culturally as well as intellectually, key decision makers, employees at different levels and expertise within the organisation, and external professionals from the industry. Furthermore, unorthodox and challenging thinkers should be included to make the execution successful.

- Scenario Building:

- All agree on defining the issue at hand by systematically identify relevant stakeholders, trends, constraints, and so forth. Hereafter, there are several different approaches to building scenarios, which should be combined as found suitable by the team. One approach suggest that starting point is taken by plotting the scenario drivers, and deriving all possible combinations from them, another proposes the initial construction of two extreme scenarios, a positive and a negative, while a third suggests that the most probable scenario chosen as the base case for the future, to have something to take starting point in.

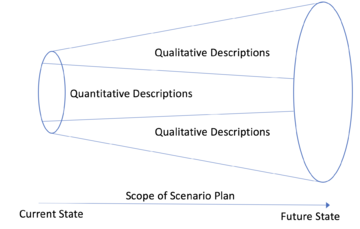

Initially the scenarios constructed should rely more on forecasts and quantitative descriptions and as the scenarios are moved further into the future the focus should increasingly be on qualitative descriptions (Amer, 2012) (see figure 2). Another starting point in scenario construction is to create nearly certain scenarios, making sure the scenarios cover a broad scope of outcomes and without ignoring extremes. This helps identifying the drivers that are already in place, thus determining near-inevitable progress, regardless of how true the final scenario turns out to be. These four kinds of predetermined drivers can be used as inspiration: (Roxburgh, 2009)

- Demography is destiny, and the trends will affect the surrounding environment.

- Laws of economy are in place, and history repeats itself.

- Technological trends often have a predictable lifetime that should be thought into a business plan.

- Often scheduled events happen sooner or later than expected.

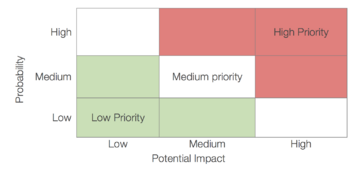

Once the scenarios have been built, they should be evaluated and tested. Depending on the situation and use of scenario planning, one way test and prioritise scenarios is using Wilsons Matrix, similar to a risk matrix, mapping the importance on probability and impact. (Figure X)

Once again, no single effective model is accepted within the field. If a more structures approach to scenario building is desired, “Schoemaker’s 10-Step Scenario Building Model” from 1993 is a usual suggestion. (Keough, 2008) Four scenario archetypes include:

- Continued growth: Current conditions and trends are enhanced

- Collapse: Continued growth fails and is followed by contradictions

- Steady state: Little or no growth, this future find balance between economy, nature, and society

- Transformation: Dramatic technological or spiritual changes cause changes in the basic assumptions that is the foundation of the other three scenario types. (Amer, 2012)

- Decision Process

After building and evaluating the scenarios, they should be presented to a key decision maker, who is able to take action on the information provided. The decision maker could have been part of the team (as previously mentioned, this aid gaining the readiness required to plan for the future), however the involvement of key decision makers in phase 3 should not be mistaken. Organisational leaders need to sit down and properly review the outcome of the scenario construction and evaluation. Assuming the scenarios are presented in an according manner to the receiver, scenario planning will reduce bounded rationality and information stickiness, and increase knowledge friction, making the decision maker more susceptible to considering options outside conventional scope, as well as bring empowerment through knowledge sharing to the rest of the team. At least four scenarios should be included in the final presentation, since people tend to go with the middle or ‘average’ scenario if three is presented, and 2 is simply too few. (Roxburgh, 2009)

- Increased Performance

The last step is to ensure that the scenarios presented are actually used to increase business performance. If regarding the Wilson Matrix used for evaluation in Phase 3, this is an example of which actions to take for each scenario in the different priorities:

- Low priority: Monitor

- Medium priority: Make contingency plans

- High priority: Prepare/include in strategy

When it comes to preparation of budgets for projects, programmes, or portfolios, scenario Planning is also useful. In volatile businesses, budgets can rapidly become outdated and need replacements due to changing conditions. Scenario planning will allow for contingency business plans and financial statements based on alternative scenarios as an example if a major customer of a company files bankruptcy, thus aiding limiting the damage caused by the change. (Seal, 2012) (Keough, 2008)

Limitations

The classic saying “All models are wrong, but some are useful” is definitely also true for scenario planning. Like all forecasts per definition are wrong, will scenarios never be entirely true, simply because reality is more nuanced and unpredictable than scenarios constructed. However, the scenarios do not have to be 100% accurate to be valuable. Another drawback using scenario planning, is that it can set traps for the unwary. Creating too detailed scenarios, can make participants and decision makers think that they have predicted what will happen, which is a threat. They need to be aware that scenarios are wrong per default, and that the industry can develop in other unforeseen ways. In the same field, it should be mentioned that unlikely scenarios should not be ignored, but their lower probably but potentially higher risk, and the difference between the two should be acknowledged. (Roxburgh, 2009)

When entering the decision process, it is, according to Henry Mintzberg, more challenging to change the managerial view to a macroscopic view allowing re-perceiving the wider environment the organisation operates in, to make scenario planning valuable, than it is to build the actual scenarios. This is obviously a challenge when applying to tool, but also what makes it worth much more than just the actions taken, once executed right. (Amer, 2012) Once this is overcome, the manager must not attempt to lead people based on multiple scenarios. One clear strategy should be chosen, but the organisation prepared for changes and adjustments to the strategy. Furthermore, it should not be assumed that all possible outcomes are covered. On the contrary, the organisation should stay alert and agile. (Roxburgh, 2009) In general scenario planning should not be used at all, if uncertainty is too high, since this can make people focus too much of unlikely outcomes of insufficient scenarios. Instead managers should recognise that no plausible scenarios can be made and stay alert to the volatile environment. (Roxburgh, 2009) The most important limitation to scenario planning may be that, according to Keough, literature generally fails to provide the information needed to properly undertake scenario planning. This makes it challenging for unexperienced managers to succeed and largely leaves it up to the individual practitioners to make the tool valuable and avoid the drawbacks mentioned.

- None of the above is rocket science. Why, then, don’t people routinely create robust sets of scenarios, create contingency plans for each of them, watch to see which scenario is emerging, and live by it? Scenarios are in fact harder than they look—harder to conceptualize, harder to build, and uncomfortably rich in shortcomings. A good one takes time to build, and so a whole set takes a correspondingly larger investment of time and energy. Scenarios will not provide all of the answers, but they help executives ask better questions and prepare for the unexpected. And that makes them a very valuable tool indeed.

- -Roxburgh, 2009

Annotated Bibliography

- Roxburgh, C., “The use and abuse of scenarios”

- Thorough walk-through of the advice on scenario planning and its advantages and disadvantages

- Keough, S.M., Shanahan, K.J., “Scenario planning: toward a more complete model for practice”

- Discussion and elaboration of a generalised scenario planning model

- Amer, M., Daim T. U., Jetter, A., “A review of scenario planning”

- Profound literature review and aggregation of tools related to scenario planning

References

- Hindle, T., (2008), “Scenario Planning”, The Economist, [ONLINE] available at: http://www.economist.com/node/12000755

- Roxburgh, C., (2009), “The use and abuse of scenarios” [ONLINE] available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-use-and-abuse-of-scenarios

- Caplice, C. (2011), “Introduction to Scenario planning”, Future Freight Flows (FFF) Project at MIT [ONLINE] available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVgxZnRT54E

- Boasson, Y., (2004), “An Evaluation of Scenario Planning for Supply Chain design”, Massachusetts Institute of Technology [ONLINE] available at: http://ctl.mit.edu/sites/ctl.mit.edu/files/library/public/theses_2004_Boasson__execsumm.pdf

- Seal, W., Garrison, R. H., & Noreen, E. W. (2012). Management Accounting(4th ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Ford, D., & Saren, M. (2012). Managing & Marketing Technology . Hampshire, United Kingdom: Cengage Learning.

- Tonnquist, B. (2009). Project management: a complete guide. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Amer, M., Daim T. U., Jetter, A., “A review of scenario planning”, Futures, Volume 46, 2013, Pages 23-40

- Keough, S.M., Shanahan, K.J., (2008), “Scenario planning: toward a more complete model for practice”, Advances in Developing Human Resources 10