The Stage-Gate Model

The stage-gate model is a project management methodology used to drive a project from idea-to-launch in a structured way, including several decision-making points, so called gates, where senior management is involved to take decisions regarding the course of the project.

The stage-gate model was firstly developed by companies as a way to manage the product development process more efficiently. However, the model being intuitively appealing and simple, it was adopted to manage a variety of other projects like process improvements and process changes. Today, it is regarded as a general project management methodology with a wide range of variations. In its latest version the stage-gate model has been combined with agile methodology for a more fast-paced and adapted response to the Voice of Customer (VoC).

A phase-gate process, a waterfall process, a front-end loading (FEL) are all very similar methodologies to the stage-gate model.

Stage-Gate® is also a registered trademark of the Stage Gate Inc., which was founded in the year 2000 from Robert G. Cooper, the creator of the stage-gate model, and Scott J. Edgett and it is an innovation consulting firm.[1] The Product Development Institute Inc.[2] also uses the Stage-Gate® trademark. It was also founded by the aforementioned in 1996 with the purpose of helping companies to improve their portfolio management and product development approaches.

Contents |

History

The Stage-Gate Model was created in the 1980s by Robert G. Cooper, a now internationally recognized expert in the field of innovation management. The Stage-Gate Model was the result of an extensive research about the new product development (NPD) practices followed by top performing companies, leading innovators and entrepreneurs, published by Cooper in 1990.[3]

Cooper continued his research activities within new product development and innovation management, which has led him to over 120 article publications and ten published books until today. Among them, there are also proposals of new versions/adaptations of the stage-gate model that try to meet the changed needs of innovation management up to the present day.

Around 2014, a new generation of idea-to-launch process was suggested, which offered more flexibility to the management of the project, by using stages that can be iterated and by adapting the model to the type of project and its needs. In 2016, an agile-stage-gate hybrid was suggested in order to cope with the need for adaptation to the extremely fast paced environment and the VoC, especially but not only for the software industry.

It is important to mention that approximately 80% of the North American companies had adopted a version of the Stage-Gate model up to 2015. Among the leading innovative companies that have implemented the stage-gate model are 3M, Abbott Nutrition, Baker Hughes, BASF, Corning, Exxon, GE, GM, Hallmark, Kellogg, Pepsi, National Oilwell Varco, Procter & Gamble, Lego Group etc.[4]

Typical Model

The model that is described here as the typical model, was the one that was developed from Cooper after researching the product innovation processes of several top performing companies back in the 1980s. The processes of these companies, although not identically the same, followed the same pattern of stages and gates recognizing that innovation is a process that can be managed. Thus, Cooper incorporated all this knowledge into one, so called typical, model.[5]

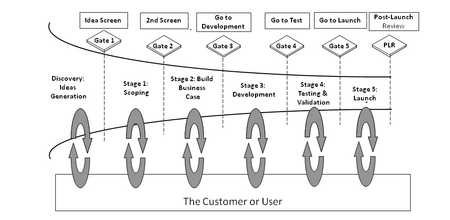

The typical Stage-Gate model is comprised of stages and gates in a linear mode, where each stage is followed by a gate. The stages are the phases of the actual work that needs to be executed in a project/ new product development and the gates are points in time when a decision has to be made about the future of the project.

Stages

A variety of activities is performed at each stage. The type of activities undertaken varies depending on the stage of the project, but also on the type of the project that is managed. The stages allow for cross-functional work and for activities to be undertaken in parallel so as to minimize the developing time and increase the speed to market. The progression of stages follows the characteristics of the project life cycle as described in the PMBOK-Fifth Edition.[6] As the stages advance there is an increase in the resources spent on the project, resulting in increased commitment from the team managing the project and the decision makers. On the contrary, the risk of the project is effectively managed stage by stage, because the number of uncertainties is reduced as the model progresses.

Gates

At the gates, the decision about the course of the project is made by the gatekeepers. The gatekeepers have a very important role which requires a good understanding of the business, the business strategy, the market, as well as having the authority to make decisions. That is why as gatekeepers usually acts the senior management of the company. Three important elements are considered at the gates:

- Input

The input at each gate is comprised of the deliverables that should be submitted in order for the project to be examined and the decision to be agreed. Usually, the deliverables at each gate are either set from the beginning of the process, chosen from a predetermined list of deliverables, or determined at the previous gate.

- criteria

The criteria are the elements based on which the project will be examined. The gatekeepers play a substantial role in setting the criteria for projects. The range of criteria may be broad, including both qualitative and quantitative criteria and it also depends on the gate and the project that is judged. Furthermore, there are ‘must meet’ criteria and ‘should meet’ criteria. The ‘must meet’ criteria are essential and must be fulfilled. Generally, the project is judged financially and in terms of its alignment with the business strategy. The ‘should meet’ criteria are not obligatory to be fulfilled but fulfilling them may be equally important to grant a GO decision. Sometimes, decision tools, like scoring boards and checklists, are used to keep track of the performance of the project and to facilitate the final decision.

- output

The output of the gate is the final decision about the project. Sometimes, part of the output can also be detailed action plans or lists of deliverables for the next gate.

The decision is usually a GO/KILL decision, but sometimes other options exist like HOLD or RECYCLE.

- GO - the project proceeds to the next stage

- KILL - the project is terminated

- HOLD - the project remains on hold

- RECYCLE - the project repeats the current stage

Explanation of the typical model

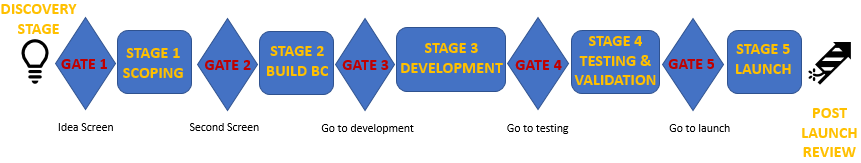

Usually, the typical Stage-Gate model is comprised from four to seven stages and gates. A skeleton of the model can be seen in the following picture:[7]

Discovery stage:

The development process is initiated by a new product idea, that is submitted in gate 1.

Gate 1: Idea Screen

The idea screen is the first decision of whether the company will commit resources to the specific idea to develop a new product. This is usually a soft decision, since the uncertainty level is still high and a second screen will follow later in the process. The project is evaluated mainly based on criteria about the alignment with the general strategy and the company’s core business, as well as the feasibility of the idea and the opportunity it offers considering the market attractiveness. If the decision is GO, it marks the beginning of a new project.

Stage 1: Scoping

The purpose of this stage is to conduct a preliminary assessment of the project, so that it can be better re-evaluated at gate 2. The assessments at this stage are more qualitative than quantitative. In particular, two types of assessments are necessary: a preliminary market assessment and a preliminary technical assessment. The market assessment will gather information about the market and will try to determine the potential future market position of the product including the market acceptance and the potential market size. On the other hand, the technical assessment will respond to questions about the product’s manufacturing feasibility including an estimation of cost and time of production.

Gate 2: Second Screen

The second screen decision is similar to the decision on the idea screen gate with the consideration of the most recent information gathered from the stage 1. At this gate additional criteria may be added, depending on the stage 1 findings, as well as additional deliverables for the next gate, should the decision be GO. At this gate the financial feasibility of the project is assessed based on the input provided (preliminary technical assessment).

Stage 2: Building the business case

At this stage the project must be clearly defined. A variety of analysis are undertaken including detailed market analysis, technical analysis and financial analysis. The market analysis is focused on what the customers prefer and how the new product will satisfy their needs. A complete competitive analysis is undertaken and concept testing is used to determine the customer acceptance. The technical analysis consists of the definition of all technical requirements for the manufacturing of the product, potentially including some design or laboratory work to completely define the manufacturing feasibility. A preliminary development plan and an operations analysis is executed. Moreover, necessary investments are estimated both in terms of changes in the current production as well as in terms of legal or patent work. The financial analysis should also be detailed including a sensitivity analysis.

Gate 3: Go to development

Gate 3 is a very important decision gate as it is the final checkpoint before the development phase, where a substantial amount of resources is required. At this point a careful examination of all the information is conducted, including the validity of the information submitted. Furthermore, if a GO decision is selected it must be accompanied by strategic decisions regarding potential choices about the new product e.g. about the final features of the product, the market segment that will be targeted etc.

Stage 3: Development

At stage 3 the actual development of the product takes place, so potential authorizations are granted (legal, patents, etc), detailed plans are produced and actual financial/cost analysis is completed. Testing plans are also prepared to be examined at the upcoming gate.

Gate 4: Go to testing

At this point the development process is reviewed and it is ensured that the new product lives up to the existing plans and quality. Any necessary changes are decided at this point both concerning the development process as well as the financial analysis.

Stage 4: Testing and Validation

Validation and Testing are the main tasks that are conducted at this stage, aiming at validating that the product is of a certain quality and that it actually meets the expectations of the customers as defined at the design and plan of the previous stages. The validation and testing stage may include in-house product tests, user and field trials, pilot production and market tests. Also, if it is considered necessary the financial analysis is revised. At this stage a detailed marketing plan is also completed.

Gate 5: Go to Launch

This is the final approval before launching the product. At gate 5 the results from validation and testing are revised and the quality of the validation and testing stage is approved. Finally, the detailed marketing plan as well as the operations plan are approved.

Stage 5: Launch

The commercialization of the product is realized at this stage. All the plans are put into motion.

Post launch review:

The post launch review is a review of the whole process and the new product which becomes now part of the product portfolio of the company. An internal audit is executed to evaluate the product development process and to pinpoint its strengths and weaknesses, so that the process can be improved in the future. Lessons learned are gathered and stored. Moreover, a complete review of the new product and its launch are completed. Financial, market and performance data are gathered and compared with the analysis predictions from the previous phases.

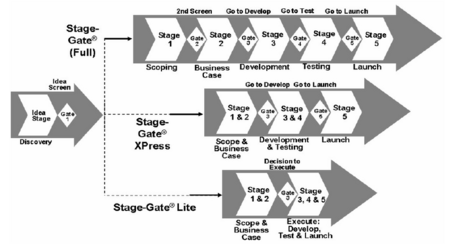

Explanation of The Triple A - variation

In 2014, Cooper suggested a new version of the model, so called the new generation of idea-to-launch system, or the triple A system. The triple A system stands for “Adaptive and Flexible”, “Agile” and “Accelerated” and it is the known stage-gate model with four additional attributes that make the model more Triple A. The attributes that were noted are the following:[8]

1. Spiral development cycles: several iterations within a single stage that make the model more adaptive. The stage may begin and develop through the iterations until it reaches a satisfying point. Each iteration follows the steps of Build – Test – Feedback – Revise, for example in the development stage it is possible to use multiple iterations of building a prototype (build) to show the customer (test), get feedback (feedback) and finally reset your thinking (revise).

2. Context-based stage definitions: this means that companies use different versions of the stage-gate model to accommodate different projects. There are three example versions of the model:

- The complete five-stage model for risky and big developments

- The light version used for moderate risk projects (3 stages)

- The express version for small development projects, usually no more than a two-stage model

3. Rik based contingency models for decision making: This attribute is used to make the process flexible and adaptable to the project at hand. The project team meets at the beginning and discusses the uncertainties of the project, defines the assumptions and decides which deliverables are needed to validate the assumptions later. So, each project is handled uniquely, there are maybe some fixed deliverables for each gate, but there are also floating ones which are based on how the team will assess the project at hand and its risk level. A drawback is that an experienced team is needed.

4. Flexible criteria for GO/KILL decisions: more criteria are needed to judge the course of the project, apart from the financial criteria. Also, more reliable financial methods should be used especially for technology projects. Research has proved that financial criteria are often wrong due to lack of appropriate data, so other criteria as well as more reliable financial criteria should be considered.

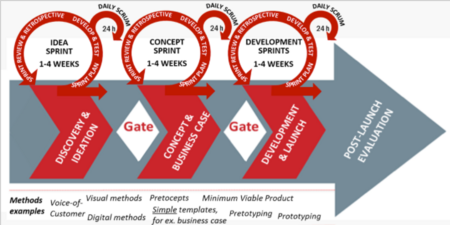

Explanation of the Agile - Stage-gate hybrid

The Agile - Stage-gate hybrid is the newest proposal regarding the stage-gate model and its adjustments in order to fit the latest product development needs. It consists of the combination of the stage-gate model with the agile methodology and the principles stated in the Agile Manifesto. [12],[13] In this integration, the stage-gate model is kept as the core of the model and the agile methodology is usually applied as a project management methodology within the stages. It is more common to use the agile methodology in the stages of Development and Testing of the classic stage-gate model. For physical product development, the scrum method seems to be the best fit.[14][15]

The scrum is an agile method, where the project is divided in several sprints, which are short time iterations, usually lasting from one to four weeks. In each sprint a specific deliverable is set at the end, that could be shown to the customer. The scrums are daily meetings where the team gathers and talks about the project, concerns are raised and the day’s work is planned. More about agile and scrum can be found here [16]and here[17].

Application

Adoption and Applicability

Several top performing companies in the 1980s were using some variation of the stage-gate model for new product development and innovation management even before the model was actually named as stage-gate by Cooper in 1990.[18] The application of the model in the fields of new product development and innovation management was adopted by more and more companies as the years passed. Characteristically, the adoption rate has reached 70-85% among the leading U.S. firms. When focusing on the world’s top corporate research and development companies (Booz Allen Global Innovation 1000) there is an 100% adoption of some form of the stage-gate model (data from 2006).[19]

Moreover, the model is applicable in a variety of industries including chemicals, financial services and consumer nondurables.[20] It is notable that the stage-gate model is also used to manage a variety of projects. Apart from the product development, innovation management and management of change/process improvements, the model is also used to manage a variety of other projects. That is why some companies have adopted the model as a general project execution model. For example, NovoNordisk is applying a variation of the stage gate model as a project execution model.[21] That is the case because the Stage-Gate model is a simple and intuitive model that can be easily modified to include more or less stages and gates and different sets of elements at the gate so as to accommodate the needs of a specific project, program or portfolio.

Similar methods

The stage gate-model and its idea of breaking a big project into steps with gates between them can also be found with different names in the literature and industry. Waterfall process[22], phase-gate process[23], phased review process[24] and front-end loading[25] are are really similar to the stage gate model.

In particular, the phase-gate process and the phased review process are stage-gate processes. They involve stages and gates, in a linear mode just like the stage-gate model. The number of stages and gates may differ slightly, but since the big idea is the same and the stage-gate model is a generic model, it may be argued that the phase-gate process and the phased review process are stage-gate models.

The front-end loading is a stage-gate model used for the planning phases, usually in procesing industries, like petrochemical, refining and pharmaceuticals. The development and testing stages are not part of this model, which focuses more on managing the fuzzy front-end.

The waterfall process is a stage-gate model, that was rapidly adopted from the software industry. The stages are very similar to the ones described in the stage-gate model, although tha last stage involves additionally the maintenance of the product. The gates are not exactly as modeled in the stage-gate model, but rather consist of certain requirements and documentation that needs to be produced.

Gain from implementing stage gate

The gains of implementing stage-gate, or similar structured process to manage innovation and new product development have been studied throughout the years. In a study from 2012 from Cooper and Edgett [27], comparing best and worst performers in new product development, from a wide variety of industries (sample of 211 best performing companies), shows that the best performers were two to three times better at successfully completing a new product development process than the worst performers. Nearly all the best performers (90% of them) had a stage-gate model in place, or some other similar structured process, to tightly manage the new product development process. The gap between best and worst performers was so big that it was argued that only applying a stage gate model was considered, in itself, a best practice.

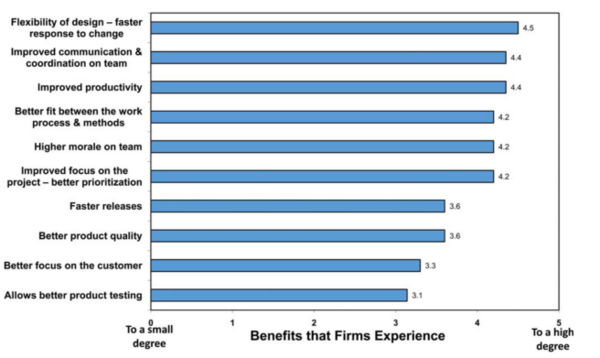

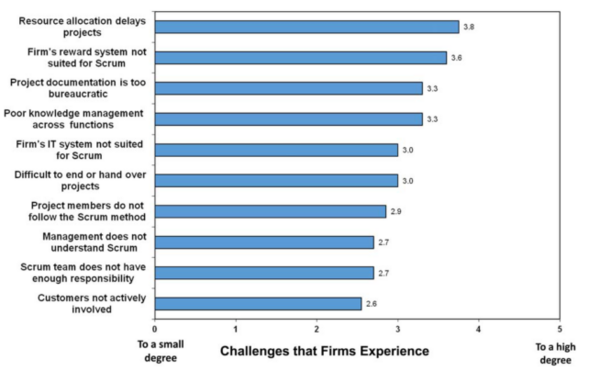

Regarding the combination of the stage gate-model with the agile methodology, Boehm and Turner [28] after examining some case examples from the IT sector, concluded that the combination of the two methodologies favors the combination of agility with discipline that future projects are going to need. Another study including cases from the software industry has also concluded that the application of an agile stage-gate hybrid has been successful. [29][30] However, the software industry is quite different from the development and manufacturing of physical products, so the question of whether such a combination would be beneficial from the manufacturing world has been posed. As a response, Sommer et al in 2015, revealed the benefits coming from the use of an agile - stage-gate hybrid process in the manufacturing world (although a small sample was used – 5 danish manufacturing firms), which can be seen in the picture.

The most obvious benefit is the faster response to changing requirements for the product, which enables the companies to have an overall more adaptive and flexible new product development process.

An example in LEGO GROUP

The Lego Group in Denmark incorporated the agile-scrum methodology into the stage-gate process of the company for the first time in 2011, in a project for a highly innovative new educational product, called "Story Starter". The results of the new method application were remarkable. The product launch was completed in just 12 months and later Lego applied the methodology to all the new product development processes.

"Story Starter" was intended for children in elementary schools and would help them become confident writers and readers. The project was initially managed through the traditional stage-gate model of the company, although a substantial amount of iterations with customer interactions was needed to develop the product. The decision of incorporating a digital documentation tool into the product was the cause of the use of an agile - stage-gate hybrid. The Digital Solutions group in Lego used an agile methodology to all their software development projects, so the new members of the "Story Starter" development team (coming from digital solutions) introduced the agile methodology to the rest of the team. The team decided to apply the agile methodology to the entire product development process, but senior management, being more conservative, insisted in integrating the agile methodology into the stage-gate model. The new hybrid model was applied to stages of development and implementation of the traditional stage-gate model. Several agile tools were used like sprints, scrums, visual scrum boards, burn-down charts, a prioritized project backlog and sprint planning meetings. Extensive customer testing took place through several sprints, during the development stage.

Main gains of the new hybrid model, as the team members noted, were the increase in team communication which led to decrease of misunderstandings and increase of the team productivity, as well as the improved work flow during the project, result of an enhanced security feeling due to the often scrum meetings.

Limitations

The typical Stage-Gate model had some limitations that the new versions of the model have tried to overcome. It has been accused of being too linear and rigid to handle innovative and dynamic projects and not adaptive and flexible enough to meet the new reality of projects and the changing Voice of Customer (VoC). Moreover, a lot of criticism has been about the decision-making points and the criteria used for decision making. It was found that in many cases financial criteria were overweight and that decisions were based on faulty financial analysis due to limited data availability.[32]

For the latest version of the hybrid agile stage-gate model, several challenges seem to lie ahead, although there is still little research on the new model and few adoptions from the industry side, up to today. Some of the challenges that should be investigated further are the following:[33]

- Defining a done sprint: defining a done sprint in the software industry is easier than in the physical manufacturing world, as not every product can be equally divided in smaller parts. Rather the sprints may focus on different versions of the product, but still this is hard to be exactly defined (it can be a drawing, a completed checklist, a physical prototype)

- Resource allocation: The agile methodology uses dedicated team members that work full time for the project. This seems to be in contrast with the cross-functional setup of the typical stage-gate model.

- Planning of the project: the stage-gate model is a long-term plan model, while the agile methodology is based on very short-term planning. In fact the stage-gate model serves as a visible roadmap for the project team.[34] It may be hard to ensure the deliverables at the gate and the focus/purpose of the project.

- When should agile be used?: the question here is whether agile is suitable for all projects, or if it works better with the riskier projects.

Furthermore, the challenges linked to the involvement of senior management and the validity and credibility of the decision-making process still remain. As the gatekeeper role is key for the stage-gate model, appointing the appropriate gatekeepers, who really attend meetings, contribute to the decision-making process and improve the gate effectiveness is very important for the success of the model.[35]

Finally, the trends in innovation management should be considered more carefully. Open innovation seems to be an interesting way of innovating that companies will probably explore more in the years to come. The stage-gate model should be examined in an open innovation framework and potential improvements should be considered.[36]

Annotated Bibliography

R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 44–54, 1990.

In this paper, Cooper explains the best practices of the best innovators in the 1980s. By studying the top performing companies the stage-gate model emerged. The model is explained deeply, and a typical model is given, characteristic of the manufacturing industry.

R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

Cooper describes the Triple-A system in detail. He explains why each attribute is necessary and again how the industry has modified the model to meet the needs of new product development.

R. G. Cooper and A. F. Sommer, “The Agile–Stage-Gate Hybrid Model: A Promising New Approach and a New Research Opportunity,” J. Prod. Innov. Manag., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 513–526, 2016.

The Agile stage-gate model is described in this paper. Furthermore, an introduction to the agile methodology is given, an example of the application of the new model in the industry and finally some suggestions for further improvement.

M. Cross and S. Sivaloganathan, “A methodology for developing company-specific design process models,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf., vol. 219, no. 3, pp. 265–282, 2005.

A very interesting paper for practitioners, about adapting the general stage-gate model to a specific company/need. The design tools proposed are really remarkable and greatly supplement the stage-gate model.

Interview of Robert G. Cooper from Planisware

In this interview, Cooper answers a lot of interesting questions and gives a very good overview of the model and its newest variations.

References

- ↑ R. G. Cooper and S. J. Edgett, “Stage Gate Inc.” [Online]. Available: https://www.stage-gate.com/. [Accessed: 30-Sep-2017].

- ↑ R. G. Cooper and S. J. Edgett, “Product Development Institute Inc.” [Online]. Available: http://www.prod-dev.com/index.php. [Accessed: 30-Sep-2017].

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 44–54, 1990.

- ↑ S. J. Edgett, “Idea‐to‐Launch (Stage ‐ Gate) Model : An Overview,” Stage-Gate Int., pp. 1–5, 2015.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., 1990.

- ↑ Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), Fifth Edition, Fifth Edit. Project Management Institute, Inc., 2013.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., 1990.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

- ↑ T. Vedsmand, S. Kielgast, and R. G. Cooper, “Innovation Management.se Integrating Agile with Stage-Gate® – How New Agile-Scrum Methods Lead to Faster and Better Innovation.” [Online]. Available: http://www.innovationmanagement.se/2016/08/09/integrating-agile-with-stage-gate/.

- ↑ “Agile software development,” WikiPedia. 2017

- ↑ K. Beck et al., “Agile Manifesto,” 2001. [Online]. Available: http://agilemanifesto.org/. [Accessed: 01-Oct-2017].

- ↑ R. G. Cooper and A. F. Sommer, “The Agile–Stage-Gate Hybrid Model: A Promising New Approach and a New Research Opportunity,” J. Prod. Innov. Manag., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 513–526, 2016.

- ↑ “Scrum (software development),” WikiPedia. 2017.

- ↑ “Agile software development,” WikiPedia. 2017.

- ↑ “Scrum (software development),” WikiPedia. 2017.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 44–54, 1990.

- ↑ Booz Allen Hamilton, “Booz Allen Study Finds the World’s Leading Corporate Innovators Stepped Up R&D Spending in 2006,” 2006. [Online]. Available: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20071016005463/en/Booz-Allen-Study-Finds-Worlds-Leading-Corporate.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 44–54, 1990.

- ↑ “Project Execution Model (PEM), APPPM WikiPage,” 2015. [Online]. Available: http://apppm.man.dtu.dk/index.php/Project_Execution_Model_(PEM). [Accessed: 30-Sep-2017].

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waterfall_model

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phase-gate_process

- ↑ https://www.designsociety.org/publication/24073/implementation_of_the_phase_review_process_in_the_new_product_development_a_successful_experience

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Front-end_loading

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper and S. J. Edgett, “Best Practices in the Idea-to-Launch Process and Its Governance,” Res. Manag., vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 43–54, 2012.

- ↑ B. Boehm and R. Turner, “Balancing agility and discipline: evaluating and integrating agile and plan-driven methods,” Proceedings. 26th Int. Conf. Softw. Eng., pp. 2–3, 2004.

- ↑ D. Karlstrom and P. Runeson, “Combining Agile Methods with Stage-Gate Project Management,” Management, no. June, pp. 43–49, 2005.

- ↑ D. Karlstrom and P. Runeson, “Integrating agile software development into stage-gate managed product development,” Empir. Softw. Eng., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 203–225, 2006.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Invited Article: What’s Next?: After Stage-Gate,” Res. Manag., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 20–31, 2014.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper and A. F. Sommer, “The Agile–Stage-Gate Hybrid Model: A Promising New Approach and a New Research Opportunity,” J. Prod. Innov. Manag., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 513–526, 2016.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper, “Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products,” Bus. Horiz., 1990.

- ↑ R. G. Cooper and S. J. Edgett, “Best Practices in the Idea-to-Launch Process and Its Governance,” Res. Manag., vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 43–54, 2012.

- ↑ J. Grönlund, D. R. Sjödin, and J. Frishammar, “Open Innovation and the Stage-Gate Process: A Revised Model for New Product Development,” Calif. Manage. Rev., vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 106–131, 2010.

- ↑ Template:Cite book