Stakeholders from a dynamic and network perspective

Contents |

TODO

- Skriv noget om det christian har forelæst om.

- Antifragily or not

- Gennemgå Reviews

Overview (NOT DONE)

The identification of stakeholders has proven as a crucial factor for the success of projects[1], due to the fact that it helps gives an overview of the current state of the analysed scenario. For this, numerous models have been developed for mapping stakeholders for knowing which, when and how to prioritise them. This type of analysis works as a macro analysis, not only framed to contain a specific area of investigation, but takes into account all the different kind of actors (person, group or organisation) that currently has an interest and that can affect, or be affected by, the give action/project

This article is based on the assumption that not only is the identified stakeholders important, but the way stakeholders are interacting will also be important for the success of a project. Therefore an implementation of Social Network Theory is considered and investigated. This proves advantageously because it will now be possible to uncover shadow networks and how stakeholders with e.g. low formal power can still be crucial to take into account, due to their informal power through their interconnection with other stakeholders. Different methods within Social Network Theory concerning centrality algorithms are discussed and examples are provided, showing how these can be beneficial for considering.

Overview of a Stakeholder Analysis today

Conducting a stakeholder analysis is done with the purpose of getting an overview of different actors that currently has an interest and that can affect, or be affected by, a give action/project. This will be useful during projects, due to the fact it will be possible to get an understanding on how much attention different stakeholders should get. When using the term “stakeholder”, it covers a broad range of actors; such as individuals, groups and organisations[2]. A stakeholder analysis is what can be characterised as a macro analysis because it not only takes into account for the organisation or a specific area of investigation, but also takes into account for the external environment. From this the analysis can be broaden to take multiple levels into consideration, which includes local, regional, national and even international [1] . This will affect the researcher and how this person will have to collect the necessary data. A “local stakeholder analysis” usually means that the stakeholders are reachable for individual interviews, which can result in more qualitatively data and otherwise the analysis has to use other kind of existing documentation, such as e.g. reports, if interviews are not a possibility.

Conducting this kind of analysis is therefore to get a more in-depth understanding about the involved stakeholders and their interest, intentions, agendas and their influence or potential resources the project could benefit/dis-benefit from [3]. From this it can be relevant for distinguish between stakeholders by categorising them as primary (crucial for the survival of the project) and secondary (important, but not essential for the survival) stakeholders [3].

Current practices, when conducting a Stakeholder Analysis

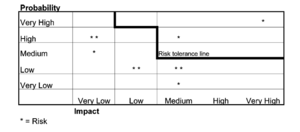

Multiple kinds of stakeholder analyses can be found in the literature [1][4] , depending on what kind of aspects is considered most important. Usually the models all have in common that they are grid based, usually in two dimensional matrix tables, where this can represent power vs. interest, see figure 1, which is just one example of several, where other stakeholder analyses could e.g. incorporate power vs. dynamism[5]. Colleting the necessary information can be divided into two subgroups; primary and secondary data gathering [1].

Primary data gathering cover direct interactions between stakeholders and researcher, which includes different kind of interviews including semi-structured, structured etc., but also the use of focus groups. The secondary data gathering is more data oriented e.g. reports, internal documentation and is usually discovered during the semi-structured interviews [1]. Current practices concerning stakeholder analyses are primarily based on primary data gathering [6], where it is usually investigated “who is important” and “who will be affected” [6]. From this perspective it can be concluded that the current practice of a stakeholder analysis, is primarily based on qualitatively data.

A more in-depth description of a traditional stakeholder analysis approach, please go to the following links:

What is missing in the current practices of stakeholder analyses

Even though a lot of the literature states, when conducting a stakeholder analysis it is crucial it is done from a dynamic and iterative perspective, very little actually states how to do this in practice[7]. This reason for this is due to the fact that as a project progress existing stakeholders may change attitude towards the project and also and new stakeholders may emerge, which needs to be taken into consideration.

Incorporating emerging stakeholders can be a difficult process, when a specific stakeholder tool has been chosen, especially if the specific model does not apply for the new identified stakeholders. From this it can therefore be concluded that existing stakeholder analyses are rigid and a consequence, by applying matrix models, is that researchers can potentially be forced to make the stakeholders fit to the matrix. From the discussed variation of different models, confusion can be common, not knowing which model would be most applicable and when it should be applied [7].

From this a stakeholder analysis has to be a more dynamic tool and recognise that not only the identified stakeholders are important, but also the way they are interacting is important. Knowing how stakeholders are interconnected can help to better forecast on the future, regarding stakeholders’ potential behaviour. Therefore current stakeholder analyses needs to be expanded to take into account for more quantitative data gathering, through e.g. questionnaires [6].

Getting an overview of how stakeholders are interacting can further help for investigating the shadow network, which is the way stakeholders are interconnected through self-organisation, and not from the perspective of the designed network, e.g. an organisational diagram [8][9]. Incorporating these interactions into a traditional stakeholder analysis will also secure less subjective opinions, when a larger quantitative collection of data is considered, regarding power, interest, influence etc.[7]. This will create a better understanding of the power structure between the stakeholders, especially due to the fact that a traditional stakeholder analysis does not always take into account for the informal power aspect.

Applying Social Network Theory into a stakeholder analysis

As mentioned earlier, a stakeholder analysis is primarily based on a qualitatively approach for how to identify relevant stakeholders from both a present and a future perspective. During projects multiple stakeholders can at some point show some sort of interest, which either can be positive or negative. This is crucial for project managers, having an idea of for what to anticipate and then how to accommodate this before it is too late. Applying social network theory (SNT) into a stakeholder analysis implies that not only are the individual stakeholders important, but also the way they are interacting is important.

The reason why the interaction of stakeholders are relevant for investigation is due to the fact that stakeholders with strong ties are more likely to be able to influence each other [10] . This kind of influence can be either positive or negative because it can indirectly also illustrate trust, respect, communication, support etc., which all can have a crucial impact for the success of getting the maximal benefit from the identified stakeholders. SNT can therefore help to discover informal power structures between stakeholders, where as formal power usually can be extracted by looking directly into the organisational diagram. The procedure for investigating power structures (looking into power, influence and interest) are explored in section " Size of nodes and edges".

Identifying the right stakeholders can also help accessing the right information and knowledge. This is due to the fact that knowledge is not only embedded in formal channels, such as books, reports etc., but crucial knowledge can also be discovered through the social interconnections [11] . Therefore identifying highly interconnected stakeholders can potentially bring a lot of knowledge forward, that otherwise would not be available.

Applying Social Network Theory

The most cost and time efficient way for gathering the relevant kind of data would be through questionnaires, which in a higher degree will ensure more quantitative data, that through SNT can be analysed. There exists several different social network analysis (SNA) programs, such as UCINET[12] and GEPHI[13], where most automatically already has incorporated a various portfolio of different mathematical algorithms, which can be used for analysing the data. Combining a stakeholder analysis and SNT, primarily two types of networks can be of great importance being able to detect in portfolio, program and project managment, which will be described further down in the article [8]:

- Cohesive Networks,

- Bridging Networks

Applying SNT can also help to get the whole picture of a stakeholder, due to the fact, when conducted the more qualitatively stakeholder analysis, through e.g. semi-structured interviews it can be very hard for uncovering hidden agendas. Incorporating SNT it is possible from a statistically point of view to uncover hidden agendas because other stakeholders can be asked for their individual opinion regarding each other interest, influence etc. towards the project. This is where the quantitatively perspective of the collected data really can create value.

Application of nodes

By applying SNT, stakeholders can be given several different attributes, either assigned by themselves or by other stakeholders. These different values (based on a scale) can be illustrated through e.g. the size of the nodes, or by color, which potentially can help detecting risks or opportunities that the researcher otherwise would not have realised. A list of different attributes can be seen below [6]:

- Themselves: Age, knowledge of the project, seniority, Attitude towards the project, interest, influence, power, involvement of the project, who they are communicating with etc..

- Assigned by others: Attitude towards the project, interest, influence, power etc..

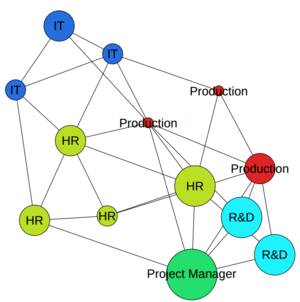

In figure 2 an example has been created for illustrating how a network could look like, where the node size represent the “Attitude towards the project”. From figure 2 it could be argued that the project manager (PM) has not spend enough time promoting the project for the IT- and Production department, due to the fact that their attitude is quite low compared to the stakeholders closer to the PM. If these stakeholders were crucial for the project, an obvious solution would for the PM to reach out to the departments, open-minded, and investigating the reason for the low attitude. Another argument why it is relevant to reach out is because one of the IT employees actually has a high positive attitude, but he is more or less only interconnected with his own department. Taking into a time/ risk perspective he could potentially over time change his opinion.

Several attributes would also make sense to illustrate through the interactions (edges) between stakeholders, but this article will only focus applying colour and changing sizes of the nodes.

Betweenness Centrality

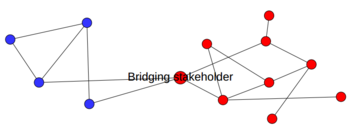

The type of network illustrated in figure 3 can be characterised as a bridging network [8]. Being aware of this kind of network can be very beneficial for a PM during projects. Stakeholders identified in the center of bridging networks are also called gatekeepers/brokers [6], which can help the PM in numerous ways. Using gatekeepers can help the PM controlling the type of information and the flow of what should be directed where. This type of stakeholder will usually have strong ties with his interconnected stakeholders, which is very common, due to the fact that as more interactions a stakeholder have, the weaker they will become[11]. Therefore a good starting point for a project would be for the PM to get the gatekeepers support so they can act as ambassadors throughout their network, when communicating the project.

This type of network is a good example of how e.g. stakeholders with low formal power actually still can have a strong influence by his informal power, due to the fact that without this stakeholder the whole network would otherwise decay and consequences of this could damaging to the success of the project.

The algorithm calculating the betweenness centrality in nodes, are based on counting how many times a stakeholder is the path between two stakeholders that are not directly interconnected (acting as the bridge) [6] [14].

Degree Centrality

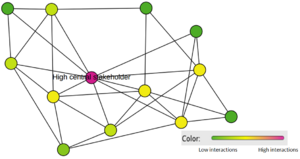

From figure 4 a network has been created, which illustrates what can be defined as a cohesive network [8]. This type of network emerges, when interactions between many stakeholders exist and especially one or few are highly interlinked. These stakeholders can also be stated to have a high degree of centrality. From figure 4 a visual illustration shows that the algorithm can colour the individual stakeholders from the way they are interconnected, where the “pink” stakeholder will be the person with highest degree of centrality.

Overall can this type of network be very important to identify, because usually there will be a lot of trust and the central stakeholders can help to bring the network together towards a project, due to their internal relations. This can again be related back to some degree of informal power. It can therefore be a good suggestion for a PM to approach this stakeholder and create an alliance instead of approaching every single stakeholder himself. As a project progresses these interrelations will probably change and it is therefore important that the the network is updated and time is spends analysing for possible trends of interrelations. Identifying these highly interconnected stakeholders can also from a cost or time perspective be very efficient because the PM can use the highly interconnected stakeholders for disseminate information throughout the network [15].

This type of algorithm is quite simple structured, due the fact that it works by counting the edges for every single node, and from that it is possible to either colour grade, or alter the size of, the nodes [6] [14].

Eigenvector Centrality

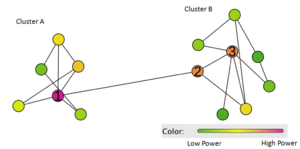

Taking into account that networks can actually be quite complex, and not as simple as figure 3 and figure 4, more advanced methods can be applied. One example of this could be the eigenvector centrality algorithm [14]. This algorithm bases the level of power of not only how interconnected a stakeholder is, but also how interconnected the stakeholder is with other stakeholders with a high interconnection density. This has been illustrated in figure 5.

Looking into figure 5, three stakeholders are of particularly interest; stakeholder one (S1) in cluster A, which properly could be the manager for the department and stakeholder two (S2) in cluster B could be another manager. These two stakeholders are both rated as higher powered, due to the fact that they are well interconnected within their own respective networks, but are also the connection between the two clusters. This could therefore illustrate a more formal power perspective. The third stakeholder (S3) is rated as an equal high powered stakeholder as S2, where S3 could be a respected employee, other trust and listen to (informal power). This will be important for a PM to look into this stakeholder because S3 and S2 could be the essential combination for creating the necessary support so the whole cluster/department would commit to the project.

Conclusion (NOT DONE)

By implementing a more in-depth quantitative SNA into the current qualitative stakeholder analysis will provide a stronger framework for identifying crucial stakeholders for focusing attention and for how to catagories the most relevant stakeholders. It will help PMs for identifying not only the formal power structure within the project, but also how the informal power also can influence the success of the project. Applying the presented algorithms will give an overview for the more active and communicative stakeholders in the network. By analysing the centrality of the network of stakeholders will help narrowing down which individuals that are crucial for approaching and convincing BLABLABLABLA.

Possible downsides for combing these methods is that it can be a more costly and time consuming process, compared to e.g. large focus groups.

- Stakeholders will not only be important for the success of a project, but also the way they are interacting.

- Heuristics

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Brugha Ruari and Varvasovszky Zsuzsa, (2000), How to do (or not to do). . . A stakeholder analysis, Health Policy and planning, Vol. 15, PP:239-246

- ↑ Solaimani Sam, Guldemond Nick and Bouwman Harry, (2013), Dynamic stakeholder interaction analysis: Innovative smart living design cases, ELECTRONIC MARKETS, Vol.23(4), PP.317-328

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Brugha Ruari and Varvasovszky Zsuzsa, (2000), Stakeholder Analysis: a review, Health Policy and planning, Vol. 15, PP:239-246

- ↑ Kennon Nicole, Howden Peter and Hartley Meredith, Who really matters? A stakeholder Analysis, Extension Farming Systems Journal, Vol.2(2)

- ↑ Gardner, J.R., Rachlin, R., Sweeny, H.W.A. (1986) Handbook on strategic planning, John Wiley & Sons Inc. Hoboken, NJ

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Lienert Judit, Schnetzer Florian and Ingold Karin, (2013) Stakeholder analysis combined with social network analysis provides fine-grained insights into water infrastructure planning processes, Extension Farming Systems Journal, Vol.125, PP.134-148

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Reed, Mark, Graves, Anil, Dandy, Norman, Posthumus, Helena, Hubacek, Klaus, Morris, Joe, Prell, Christina, Quinn, Claire, Stringer, Lindsay, ( 2009), Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management, Journal of Environmental management, Vol.90 (5), PP.1933-1949

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Battilana Julie and Casciaro Tiziana, (2013) The Network Secrets of Great Change Agents, Harvard Business Review, PP.62-68

- ↑ Shaw Patricia, (1997), Intervening in the shadow systems of organisations, Journal of Organisational Change Management, Vol.10(3) PP.235-250

- ↑ Prell Christina, Huback Klaus and Reed Mark, (2009) Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in Natural Resource Management, Society and Natural Resources, Vol.22 PP.501-518

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Prell Christina, Hubacek Klaus, Quinn Claire, Reed Mark, (2008), ‘’Who’s in the Network? When Stakeholders Influence Data Analysis’’, Syst Pract Actions Res, Vol 21, PP.443-458.

- ↑ UCINET Homepage, accessed 30.11.2014

- ↑ Gephi Homepage, accessed 30.11.2014

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Wasserman Stanley, Faust Katherine (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521387071.

- ↑ Freeman Linton, (1978), Centrality in Social Networks Conceptual Clarification, Social Networks, Vol.1, PP.215-239