Beyond the Triple Constraint

Developed by Ellen Trovåg Amundsen

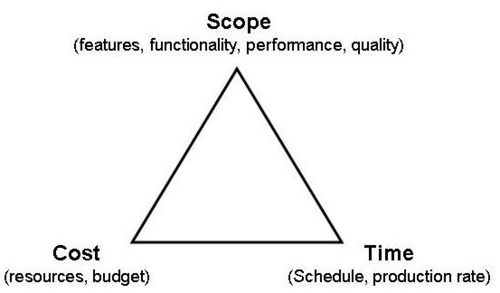

To define project management success, the Triple Constraint (also called the Iron Triangle) has traditionally been applied in order to balance between key factors that constrain the overall project delivery. Regardless of a project´s size and degree of complexity, there will always be constraints to bear in mind throughout the whole project. The Triple Constraint model points out that a project manager is assumed to reach a reasonable and balanced trade-off between competing and visible constraints (time, cost and scope). All of the three constraints are clear benchmarks against which to judge success when a project is finalized. But, in order to be able to use the constraints as objectives, the project manager needs to understand what each constraint is implying and how the three constraints interrelate with each other.

After including quality as one of the key constraints, other constraints have also proved to be an essential part of project management, such as; Benefits, Resources, Customer Satisfaction, and Risk. Moreover, a successful project needs consistently good risk management, ground rules for communication and behavior, and awareness around a stakeholder´s needs for motivation and confirmation. Some of these are called “soft pyramid sides” of the triangle and are related to internal satisfaction, which has traditionally been considered as complementary to the core trade-offs of the Triple Constraint. This will in many cases not be sufficient enough.

Regardless of the model´s shape, the constraints depend greatly on each other and will be adjusted depending on the particular project. This paper will outline the traditional approach of the Triple Constraint, together with some project success factors beyond the three primary objectives. In addition, the relationship between the new and classic constraints will be illustrated.

Contents |

The Triple Constraint

The Triple Constraint model is classically formed by three dimensions; time, cost and scope, where one side of the triangle cannot be changed without affecting one/both of the other sides. Briefly explained, scope represents the total amount of work involved in delivering a project, cost/budget refers to the total costs of carrying out the project and schedule/time reflects the estimated or allotted time set till project delivery.

The model has been used since the 1950s, and project managers have been measured by their ability to balance the key constraints of scope, cost, and schedule. In the past, projects had somewhat more certainty in outcomes, as the main source of uncertainty was in the technology that was taken into use. The model was used to provide metrics for management measurement, evaluation, and control, resulting in a clear and visible evaluation of how well projects were carried out after they were finalized. In addition, the model provided success criteria for evaluating options for decision-making.

George E. P. Box stated "All models are wrong. Some are useful" (1979)[1]

Since the 1950s, the uncertainty in projects has increased, mainly caused by rapid market changes, resulting in a reduction of the model´s efficacy. This implies that it is impossible to determine a fixed scope, cost, and schedule in advance of any project. Together with increased uncertainty, the constraints of the classical Triple Constraint model start to cause, not solve, issues. Therefore, if a project manager chooses to use the model, the focus will continue to be on satisfying the constraints, rather than focusing on customer satisfaction. This will result in project delivery within the allotted time or near budget, but without satisfied customers.

Application

According to PMBOK® Guide, the definition of a constraint is [2]: “A limiting factor that affects the execution of a project or process”. The constraint can be both internal and external to a project, but will in some way affect the performance of a project.

The relationship between the three constraints

As already mentioned above, the three constraints are closely interrelated to each other, and thus, if a project is required to change one of the constraints, the others will be affected. Firstly, there is a direct and essential relationship between time and cost. If the time scheduled for a project is reduced, either the budget needs to be increased or the scope needs to be reduced. Or in case of an exceeded project schedule, it will immediately be costlier for the company to carry out the project. Additionally, the costs estimated are almost certain to be overspent in case of a delayed project start or fulfillment.

According to the PMBOK® Guide (page 6)[2]:

“The relationship among these factors is such that if any one-factor changes, at least one other factor is likely to be affected. For example, if the schedule is shortened, often the budget needs to be increased to add additional resources to complete the same amount of work in less time. If a budget increase is not possible, the scope or targeted quality may be reduced to deliver the project’s end result in less time within the same budget amount. Project stakeholders may have different ideas as to which factors are the most important, creating an even greater challenge. Changing the project requirements or objectives may create additional risks. The project team needs to be able to assess the situation, balance the demands, and maintain proactive communication with stakeholders in order to deliver a successful project.”

All of the three constraints are clear benchmarks against which to judge success when a project is finalized. But, in order to be able to use the constraints as objectives, the project manager needs to understand what each objective implies. Moreover, there are several examples of time-related costs, such as;[2]

- The effect of project delays on direct costs; cost inflation occurs when a project starts later than predetermined. Additionally, there will be other causes of inflation, that are less easily quantifiable, e.g. when work beyond scheduled time contributes to a further inefficient work performance.

- The effect of project delays on indirect (overhead) costs: in case of a delayed project, indirect costs will have to be borne for a longer period than planned.

- The effect of project delays on the costs of financing; in case of an extended financing period, the total amount of interest or notional interest payable will increase correspondingly.

Most projects have deadlines, and the purpose of these is to keep a schedule within a planned deadline and prevent usage of resources long after the original purpose of the project is forgotten. Worst case scenarios related to time-related costs could potentially be unavoidable cost penalties, which can occur if the project exceeds its deadline. This means that the contractor fails to meet the contracted delivery obligation and to avoid this, all projects should aim to monitor and control costs through an achievable plan, so that the project proceeds without time extending disruption.

When talking about the "budget" of a project, it can be in terms of both money and effort needed to carry out the project. While “scope” refers to the outcome of the project (“products” in PRINCE2™[4] terminology), and consists of a list of deliverables that need to be addressed by the organization responsible for the project. When the definition of the scope is clear and sufficient detailed, a project manager will lower the chance of any great variation in cost and time. On the other hand, if a project is poorly defined, there is a bigger chance that the triangle will change its shape by great differences.

Beyond the classic Triple Constraint

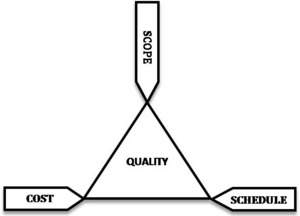

Quality constraint introduced

The term "quality" was fairly early included as a supplement or replacement for scope, or as a fourth limitation to the classic model. The main difference between quality and scope is that quality focuses on the characteristics of a deliverable. When describing a project, there is nothing called “high/low quality”. The reason for this is that the definition of “quality” varies according to the stakeholder´s requirements. From a stakeholder perspective, expectations regarding quality are based on individual scope, time and cost limitations. Hence, quality is another triangle within the original iron triangle, where all three sides are linked to the outer boundaries. So, in order for a project to meet its maximum quality level, the inner three-sided quality triangle has to meet the outer triangle, given limitations of scope, time and cost.

Moreover, the quality constraint works in the same way as the other constraints. And there are many classic examples of projects where both cost and time were tightly constrained, which resulted in less testing and verification of quality. In these cases, the model had quality as one of the three corners (substituting scope).

In more recent year organizations, total quality management (TQM) has been increasingly embraced. In TQM, a “culture for quality” is created throughout any organization, with quality shared by all from top management downwards. Furthermore, the ISO 9000 series of standards[6] is known as a set of standards to run an efficient quality management system, aimed at creating a quality culture for the entire organization. (The International Organization for Standards (ISO) publishes ISO9000 series and a full range of other international standards.[6])

Limitations of the Triple Constraint

The shortened version of the Triple Constraint model says: “cheap, fast or good? – choose two”

There is a key problem to question; in fact, there are only two factors in the model. Firstly, “scope” refers to the project´s deliverables, which will increase in case of increased effort and time required. Secondly, “cost” is defined by multiplying a cost by duration (time). Thus, “cost” contains “time”, that builds on the saying “time is money”. So, therefore, time is not a separate factor. In addition, time is also a relative factor, meaning that a dollar in project A is worth the same in project B. But, one month delay for project A can have a completely different impact on Project B, although the delay is similar to both projects.

Finally, time and cost are not always sufficient ways to measure the business value of a project; many projects are delivered on time and on a budget, but still, they don’t deliver sufficient business value. On the other hand, over budget and scheduled projects have also proven to deliver significant business value. An example of this is the Sydney Opera House, which was a project management failure 14 times over budget and took 15 years to build. In spite of this, the results based on engineering work, architecture and social benefits are undoubtedly characterized as successful.

What is project success?

So, what is project success? Project success can be defined as the value of the project when the result or product is taken into operation. There are a lot of different indicators to measure this success, such as; achievement of impact goals, achievement of purpose, customer satisfaction, achievement of strategic goals, economical aspects, competency enhancement, and reputation, etc. [7]

In the PMBOK® Guide [2], project success is clearly described to be; “measured by product and project quality, timeliness, budget compliance, and degree of customer satisfaction”. (page 9)[2] Furthermore, success is determined by the project team’s “appropriate processes,” “approach…to meet requirements,” and ability to “comply with requirements to meet stakeholder needs,” and “balance…competing demands of scope, time, cost, quality, resources, and risk” (Page 37)[2]. Additionally, teamwork is described as an essential part of successful projects (p. 229)[2]. In conclusion, this explains that there is more to success than the three main constraints of the Triple Constraint model. So, as it is noted in PMBOK® [2] , the factors mentioned should not be the only constraints to balance, but they should be integrated along with critical constraints and success measures of the organization and project stakeholders.

Furthermore, in order to extend the application of the Triple Constraint, there are proposed different sides of possible new models [8] [9];

- measure expected and actual business success

- help to focus on where the opportunities lie

- help to take the right decisions effectively

- present net value delivered by a project AND by the project management process

An alternative model should aim to move the focus from the project manager to project management as a whole. To engage both management and customers and to allow a project manager to handle conflicting demands by providing a measurement including the total effect of cost, opportunity, and schedule. To introduce a capability component is one possible concept. Capability refers to the underlying value-added processes used to carry out a project. [8]By understanding and measuring capability, the great potential could be found concerning improving the delivered value through projects. This would require process management skills in order to be successful.

Another approach to project management is to consider the three constraints as finance, time and human resources. So, in order to deliver a project before the deadline, more human resources should be added. This would raise the cost of the project unless it would reduce costs to an equal amount due to the early project delivery. A triangle with time, resources and technical objective as the sides of the triangle, instead of corners, shows this graphically.

The Six Star Constraint Model

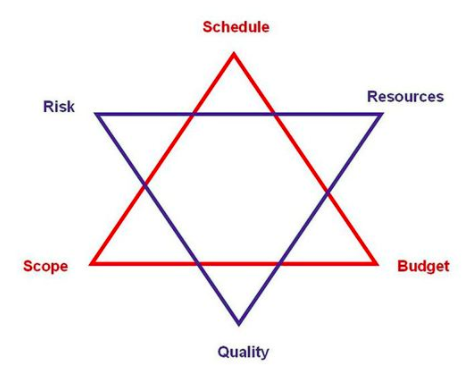

PMBOK® 4.0[2] presents a model based on the triple constraint, but includes six constraints to be monitored and managed. “Balancing the competing project constraints, which include, but are not limited to: scope, quality, schedule, budget, resources, and risk".

The model is illustrated as a six-pointed star, maintaining the triangle analogy. [10] The star also represents the relationship between project input/output factors on one triangle and the project process-factors on the other.

As already mentioned, since the 1950s, the awareness of project-related factors has increased. In PRINCE2™ [4], the factors have been identified through its focus on tolerance. PRINCE2™[4], has also added the quality term as a distinct factor, in addition to the three core factors, along with benefits and risk. The last two elements here are the newest, but they are already implemented in projects and can be found in the PMBOK® Guide's [2] process groups (Page 5). By not including these two constraints, they can produce a negative impact and consequences of a project.

Benefits represent a project´s expected “value” to the organization, which the project´s deliverables (project´s scope) are expected to produce. According to PRINCE2™ [4], a Business Case with measurable, clear and agreed benefits are required, or else the project should not be started. Or, in case the justification disappears, the project should be canceled. Both internal and external factors affect the benefits, so if there is a change in circumstances, a project might not be worthwhile continuing, although the classic constraints are meeting expectations. This is a common situation, and with the classic Triple Constraint model, one might not be aware of the benefits needed to assess the viability of the project. In case of higher potential benefits than planned, the stakeholders/project manager/sponsors may consider investing more time or money, or expand the scope, to exploit the potential advantage.

A project´s risk needs to be addressed as well and managed through risk management tools. There is always a certain level of risk that is approved, commonly expressed as a project´s risk tolerance. Risk must be identified and thoroughly examined, to identify their potential impact on the project. There is a complex interaction between the six constraints; in case of changing scope or quality, the benefits will hopefully be increased, but this will additionally increase risk. On the other hand, risks can be both “opportunities” and “threats”, so by taking greater risks the benefits may potentially be increased or they might be damaged. If the project schedule is increased, there might be more time for better quality testing, or it can result in increased risk because the product may be introduced to its market too late. Thus, the six constraints highly influence each other throughout the whole project. [11]

Conclusion

The Six-Star Constraint model is used to control the project, and the constraints set guidelines for the project managers to get a picture of what the stakeholders/sponsors of the project requires, in addition to the overall performance acceptability limits. In the event that it is not possible to control high risk, sponsors/stakeholders need to decide whether they are willing to take the risk involved with the project, or not. To achieve a successful project fulfilment, PMBOK® Guide has pointed out the involvement of stakeholder (Page 6)[2] by; "Addressing the various needs, concerns, and expectations of the stakeholders in planning and executing the project", as well as "Setting up, maintaining, and carrying out communications among stakeholders that are active, effective, and collaborative in nature" and "Managing stakeholders towards meeting project requirements and creating project deliverables".

If one of the six constraints are exceeded, the project manager has to consider a potential corrective action plan with inputs from the stakeholders. Additionally, the way to handle these constraints should be part of the Project Management Plan, together with change management control and communication. It is fundamental to have a well-functioning change management strategy in order to inform and verify changes with stakeholders. If the changes are comprehensive and somewhat critical for the fulfillment of the project, stakeholders will always decide further project procedure. This requires proper communication between project team and stakeholders. But it is also important to remember that, ultimately, it is impossible to satisfy all stakeholders, but still they all have to be thoroughly informed about the business case from start.

In conclusion, the success criteria of project management should include the objectives of all stakeholders throughout the project lifecycle and at all levels in the project management process. Stakeholders have different ideas as to which factors are the most important, which creates a greater challenge. Additionally, by adding more constraints to the traditional Triple Constraint model, there will also potentially be added more risks. The project manager/team needs to handle this by balancing the constraints and demands, through a proactive communication with stakeholders. Finally, with a multitude of objectives, it is somewhat possible for the project manager/team to create an illusion of the requirements of project success.

Annotated bibliography

- Lock: Project Management (10th Edition): Mainly principles and practice of project management, with some chapters about implementing change management projects and the role of senior managers in supporting projects.

- Project Management Institute. (2004) A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK®) (Third ed.) Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute: PMI global standards providing guidelines, rules, and characteristics of project, program and portfolio management. These standards are widely accepted and provide fundamental practices needed to achieve organizational results and excellence in the practice of project management.

- Project Management (2009): "Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2": Providing a universally applicable project management method, including principles, processes and techniques enabling individuals and organizations to successfully deliver projects within time, cost and quality constraints.

- Caccamese, A. & Bragantini, D. (2012). Beyond the iron triangle: year zero. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2012—EMEA, Marseilles, France. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.: An article presented by the Project Management Institute PMI and was originally published as a part of 2012 PMI Global Congress Proceedings – Marseille, France. The article identifies the "soft pyramid" sides of the classic Triple Constraint model, with some factors and tools related to the model and some practical tips for a "year zero" awareness of the "soft pyramid".

References

- ↑ "Baratta, A., The triple constraint: a triple illusion, Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress, North America, Seattle, WA. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute., (2006):.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Project Management Institute, "A guide to the project management body of knowledge: PMBOK Guide", Project Management Institute, (2000):.

- ↑ "Project_Management_Triangle", Apppm 42433: http://apppm.man.dtu.dk/index.php/Project_Management_Triangle, (2016):.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2", Office Of Government Commerce, (2009):.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Project_management_triangle", https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_management_triangle:.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "ISO 9000 Standards", https://www.iso.org/standard/42180.html:.

- ↑ "Freeman, M. & Beale, P., Measuring project success, Project Management Journal, 23(1), 8–17., (1992):.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Rahschulte, T. J. & Milhauser, Beyond the triple constraints: nine elements defining project success today., Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—North America, Washington, DC. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute., (2010):.

- ↑ "Graham, R. J. & Cohen, D. J., Beyond the triple constraints: developing a business venture approach to project management., Paper presented at Project Management Institute Annual Seminars & Symposium, Nashville, TN. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute., (2001):.

- ↑ "Siegelaub, J. M., Six (yes six!) constraints: an enhanced model for project control., Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2007—North America, Atlanta, GA. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute., (2007):.

- ↑ "Lee, W., Manager's challenges—managing constraints, Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—Asia Pacific, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute., (2010):.