Risk Management-Identification

Developed by Maria Eileen Hubbuck (s210444)

Risk identification is necessary for all projects, programmes and portfolios that strive to achieve a set of objectives with success. The international standards made by the Project Management Institute(PMI), PRojects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE2) and the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) addresses tools and techniques in order to perform a successful identification process for project, programme or portfolio managers. The standards highlight the importance of handling the objectives. However, successful risk management involves more than listing identified risks. Risk identification is an iterative process in an ongoing life cycle for projects, programmes or portfolios and demands the identified risks to be structured in a way that matches their complexity and level of impact. Adopting identification techniques such as brainstorming, risk checklists and risk breakdown structure are necessary actions in order to output a thorough risk register, risk report and perform revision of project documents. Some key success factors for risk identification, amongst others, are the implementation of effective and clear communication, early and comprehensive identifications, inclusion of risks both as threats and opportunities, individual and overall risks and include a variety of departments for multiple risk perspectives.[1][2][3]

Contents |

Why identify risks?

A risk is defined as the uncertainty of an event, that if occurs, impacts the event either in a positive or negative manner [1]. When managing projects, programmes or portfolios, it is vital to identify and manage risks in order to prevent negative and benefit from positive outcomes. Risk management is a common practice and lies within the planning stage of project management. According to the “Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects” published by PMI[1], identifying risks is the second out of seven stages within the risk management life cycle. Hence, identifying risks is one of the early stages of risk management and a necessity in order to pursue further risk management actions and prevent a negative impact on the projects’ success.[1]

Context and Application

Risk identification is applied for projects, programmes and portfolios, whilst the techniques might vary due to complexity and size. As a part of the risk management life cycle, it is an important stage within the planning phase of risk management but is dependent on the following active steps in order to be put to practice and cause risk prevention. For a manager of either a project, programme or portfolio, risk identification is a practice that, if omitted, might lead to project failure.[1][2][3]

In 2019, PMI published the international standard “Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects” PMIStandard. The standard is put to practice worldwide and is a tool for project, programme or portfolio managers to achieve success. PMI divides risks into two categories; individual risks that effect one or more objectives and overall risks as the uncertainty of the whole project, programme or portfolio that arises as a collection of all sources of uncertainty. Both individual and overall risks are important to identify within the identification process. Additionally, they address the risks with positive outcomes as opportunities and risks with negative outcomes as threats. The separate terms are applied to distinguish the possible outcomes and effects of risks within projects, programmes or portfolios. Other terms used to distinguish and characterise risks are conditional risks that will occur as an effect of another risk occurring. The term correlated risks is used for risks that vary accordingly due to a fixed correlation. Independent and dependent risks are also two terms addressed when stating the dependencies of two risks to one another. The wide termination of risks serves as a purpose to initiate structure and to differentiate them from one another.[1][5] In addition to PMI, ISO and PRINCE2 are two practiced standards that differ slightly from the methodology given by PMI. In terms of risk identification, PMI is the only standard that addresses the life cycle term, whilst ISO and Prince2 lists identification as either the first or second step within the procedure of risk management identification. However, all sources address the importance of risk management as a continuous procedure, as risks are not only to be identified at the beginning of a project, but is a continuous process from the projects’, programmes’, or portfolios’ initiation to completion. Hence, the methodology given by PMI, addressing risk identification as a step within a life cycle, amplifies the importance of the practice throughout the whole project.[1][2][3]

Inputs

In order to carry out the identification process, it is vital to have information about the projects’ scope in the form of a project management plan, project documents, agreements, procurement documentation, enterprise environmental factors and organisational process assets. Together they form the inputs of the identification process. Therefore, it is of great importance to have established communication with managers, stakeholders, senior management, potential customers and all other active participants in the project, programme or portfolio in order to include all possible perspectives on risk identification. [3][6]

Techniques for risk identification

There is no specific technique that is strictly related to risk identification. However, all the addressed international standards list a selection of several techniques that can contribute to a thorough risk identification. The aim is to document the predictable risks and recognise that there might arise risks that are unpredictable from the current risk identification stage.

Brainstorming

The term brainstorming was first introduced in the book How to “Think Up” by Alex Faickney Osborn in 1942 as a unique technique incorporated by the advertisement agency BBDO. However, the term was not populated before Osborn published the book “Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Problem Solving” in 1953[7][5]. The principles of brainstorming might have been associated differently and used by several teams before Osborn addressed the term. However, since 1953 brainstorming has been the term used worldwide as a group creativity technique in order to obtain a list of spontaneous ideas and thoughts related to a specified topic. The idea of brainstorming in risk identifications is to gather all potential risks from a variety of disciplines within the project, programme or portfolio team and form a list of individual and overall risks. There are no strict boundaries, but the brainstorming may be divided into different project categories in order to structure the process. All thoughts should be noted down without criticism in order to broaden the framework and identify risks that might not be obvious by first glance. [1][7]

Risk Checklists

Based on historical projects, programmes or portfolios with a comparable background, one can establish a risk checklist. The purpose of this checklist is to present individual risks that have occurred before and that might occur during the lifetime of the project, programme or portfolio. In order to use a checklist as a risk identification tool it is vital that the checklist is updated and covers risks from a variety of professions. As checklists might omit relevant risks that are not addressed as a historical risk, it is necessary to combine the technique with other risk identification techniques to identify all relevant risks. [1][6][2]

Risk Breakdown Structure (RBS)

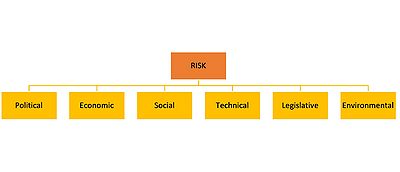

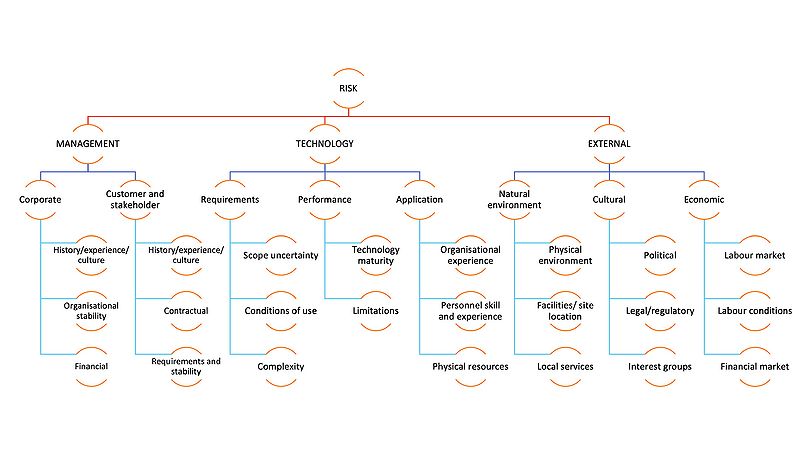

A risk breakdown structure (RBS) is a hierarchical decomposition of potential sources of risk (Source Prince2). The structure aims to divide the risks into specific domains with enhanced detail and further subdivisions. The purpose of RBS is to make a detailed overview for the manager of the project, programme or portfolio of the different sections that the risks correspond to. There are several ways to organise the risk breakdown structure and each risk may be broken down differently according to complexity and size. In PRINCE2, the PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technical, Legislative, Environmental) division is described as one of many generic subdivisions that can be implemented for a wide range of projects, programmes or portfolios. In addition to PESTLE, the guidebook for PMI addresses TECOP (technical, environmental, commercial, operational, political), and VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity) as two other relevant generic structures suitable for RBS. [6]Figure 2 is a graphical representation of the template model and should be modified into further specific and relevant subdivisions when put to practice.

An additional general RBS is to be depicted in Figure 3[9]. The figure is modified for the purpose of this article and illustrates a universal and general decomposition made by the Risk Management Specific Interest Group of the Project Management Institute (PMI Risk SIG) and the Risk Management Working Group of the International Council On Systems Engineering (INCOSE RMWG). The model breaks down the different risks associated to the categories: technology, management and external.[6][2][10]

Interviews

For projects, programmes or portfolios with a strong connection or correlation to a historical and similar event one might strongly consider interviewing stakeholders, project managers, project participants or other persons in expertise. The aim of the interview should be to identify possible risks that they have experienced or new risks that they feel are relevant. In order for the interviews to be used as an identification technique it is vital that they are documented and support confidentiality contracts. [6]

Additional analytical tools

Tools within data analysis can be used during the process of risk identification in order to investigate existing project, programme or portfolio data.

Document analysis

- Uncertainty, imprecise definitions or lack of clarity within the project, programme or portfolio documents may be an underlying risk. Through an investigation of the documents and the different assets associated can help identify risks and clarify unclear statements.[6]

Analysis of existing assumptions and constraints

- Existing assumptions and constraints covered in the project management plan may need to be further analysed in order to prevent any risks within the assumptions and constraints themselves.[6]

SWOT analysis

- The analytical technique SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) is a data analysis tool which, in risk identification, aims to broaden the identification perspective. As SWOT look not only at the specific project, programme or portfolio but also the organisation, it takes a step back to identify risks given by the environment. [6]

Root cause analysis

- In order to identify what risks that may occur from a known problem, one can use root cause analysis. Whilst root cause analysis generally aims to identify the causes and effects of a project, programme or portfolio problem, the tool can be utilised to further identify what risks that are linked to the effects. Identifying these risks will lead to a broader analysation and evaluation of the problems addressed.[6]

Outputs

Risk register

The aim of identifying risks is to gather them in a risk register that can actively be used by all active participants of the project, programme or portfolio. The risk register includes a thorough list of all risks identified with detailed information of their potential cause and effect. A specific risk owner may be addressed in order to specify the person or team responsible for monitoring and managing the risk. Possible responses to the risks should be included for the those of predictable outcome. The complexity of the risk register and the length of each risk description will differ from the context of the project, programme or portfolio.[6] p.417

Risk report

In addition to the risk register, a risk report can be composed in order to address the overall risk of a specific project, programme or portfolio. The risk report includes summaries of all individual risks and to which extent they impose a threat or opportunity to the project, programme or portfolio as a whole. Tools such as metrics, trends, or risk rating systems may be implied in order to inform the project manager and all relevant parties of historical data, statistics and degree of threat that the identified risks can cause. [6] p.418

Revision of project documents

Lastly, the outcome of the identification process might have affected the initial assumptions and must therefore be re- assessed. This is an important process in order to include new aspects and concerns from the risk identification stage. For future projects it can also be relevant to compose a register of the tools and techniques used in the specific project, programme or portfolio in order to document what methods that were beneficial to use and which methods that didn’t serve a significant purpose during the risk identification process.[6] p.418

Key success factors for identifying risks

A selection of key success factors for identifying risks are listed below. [1] [10]

- Early identification

- Manage risk identification as an iterative process

- Comprehensive identification

- Include both the identification of threats and opportunities

- Include a variety of departments for multiple perspectives

- Include both individual and overall risks

- Effective and clear communication

- View all stakeholders and contributors critically to minimise bias

- Use the agreed risk terminology

- Apply the agreed suitable risk identification techniques

Limitations of the current identification standards

Some limitations of the international standards are presented below:

- It might be challenging to identify risks if working in a new environment with little historical background.

- There is no indicator as to how long time one should spend on risk identification. It is crucial to decide upon a reasonable timeframe for identifying risks as too much focus could end in slower project, programme or portfolio process and hinder success.

- The standards are general and cover a widespread of professions. Not all techniques will be suitable for every scenario and

- The experts’ bias should be taken into account during risk identification. If the outcome of the project, programme or portfolio will benefit the expert team in a certain way then it is vital to be sceptical as to which extent they are trustworthy. Including a third part or a similar project team can help to prevent expert bias.

Annotated bibliography

Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI)(2017), Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition)

- This book is an updated PMI flagship publication released in 2017. It contains a guide of project management and the updated 2017 standards. Chapter 11 addresses Project Risk Management, herein identification of risks.

Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI)(2019), Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects

- The book expands the PMI's popular reference, «The Practice Standard for Project Risk Management». It addresses the term life cycle in connection with risk identification and divides the management of risks into different sections for project, programme and portfolio management.

Munier, Nolberto (2014) , Risk Identification. In: Risk Management for Engineering Projects

- Munier addresses the practice of risk identification specifically targeted to different fields of engineering. In chapter 4 Risk Identification he emphasizes the importance of RBS and presents a variety of different ways to structure the RBS recording to specific engineering projects

Hillson, David(2003), Using a Risk Breakdown Structure in project management

- Hillson is a Director of Project Management Professional Solutions Limited(PMProfessional) in the UK and an active member of the Association for Project Management (APM) and the Project Management Institute (PMI). In this article he urges “the need of structure” within risk identification and presents the concepts and importance of RBS.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Project Management Institute, Inc.(PMI) (2019), Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 AXELOS (2017), Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2 2017 Edition

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Project Committee ISO/PC 236 (2012), Project management, ISO 21500 Guidance on project management

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedred - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Munier, Nolberto (2014) , Risk Identification. In: Risk Management for Engineering Projects

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Project Management Institute, Inc.(PMI) (2017), Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Eleazar, Hernández (2017), Brainstorming p.57-58. In: Leading Creative Teams Management Career Paths for Deigners, Developers, and Copywriters, APress

- ↑ Inspired by: AXELOS (2017), Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2 2017 Edition

- ↑ Inspired by: Hillson, David (2003), Using a Risk Breakdown Structure in project management

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hillson, David (2003), Using a Risk Breakdown Structure in project management

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "Red" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.